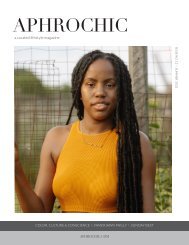

AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 8

This issue is about revolution, remembrance, and rebirth. In Dubai, Chef Alexander Smalls is launching a first-of-its-kind food experience celebrating the culinary revolution taking place in Africa. In New York, as fashion week returned, House of Aama launched a collection remembering the elegance of 20th century Black resort towns. In Philadelphia, Chanae Richards is carving out space for rest, relaxation and meditation. And in Los Angeles, our cover star, Jennah Bell, is part of a renaissance of music that is indie, soulful and written from the heart. In this issue we take you to The Deacon hotel designed by Shannon Maldonado. And in our Wellness section, we let you in our own road to rebirth, through the journey with long-haul COVID that has defined our life this past year. In our Reference section we explore new thoughts on the African Diaspora. Looking beyond the history behind the word to explore the idea itself, opening new worlds of possibility as we begin working to understand what the African Diaspora actually is. And we take you inside the importance of the emerging Black art scene heralded by the Obama portraits which, now well into their national tour, made a memorable stop at the Brooklyn Museum.

This issue is about revolution, remembrance, and rebirth. In Dubai, Chef Alexander Smalls is launching a first-of-its-kind food experience celebrating the culinary revolution taking place in Africa. In New York, as fashion week returned, House of Aama launched a collection remembering the elegance of 20th century Black resort towns. In Philadelphia, Chanae Richards is carving out space for rest, relaxation and meditation. And in Los Angeles, our cover star, Jennah Bell, is part of a renaissance of music that is indie, soulful and written from the heart.

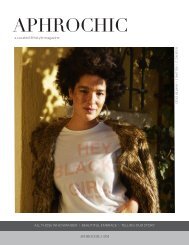

In this issue we take you to The Deacon hotel designed by Shannon Maldonado. And in our Wellness section, we let you in our own road to rebirth, through the journey with long-haul COVID that has defined our life this past year.

In our Reference section we explore new thoughts on the African Diaspora. Looking beyond the history behind the word to explore the idea itself, opening new worlds of possibility as we begin working to understand what the African Diaspora actually is. And we take you inside the importance of the emerging Black art scene heralded by the Obama portraits which, now well into their national tour, made a memorable stop at the Brooklyn Museum.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Sounds<br />

AC: So it was in New York that you went more into the<br />

singing part of your your path?<br />

JB: It's funny, I was singing the songs, but I was still not<br />

thinking of myself as a singer. I grew up with a very specific idea<br />

of what a singer was. Etta James was a singer to me. Chaka Khan<br />

was a singer to me. But I didn't sing like that. So I wasn't thinking<br />

that I could sing at all. So I was still hyper-focused on the songwriting<br />

part of it. And while I was in New York I was introduced to<br />

this poetry community called The Strivers Row. I signed on with<br />

them, and started doing shows. And then it became more interesting<br />

for me — it's how people were responding to not only what<br />

I was saying, but what I was presenting musically. <strong>No</strong>w, thinking<br />

about my voice in terms of how it's changed over the years, just<br />

with getting older, the things I can and can't do; I think singing is<br />

much more of a study for me now, because I have to learn how to<br />

navigate a body and muscles and things that are going through<br />

their own natural process. So I can't approach them the way that<br />

I used to, and I have to think about what I eat, if I exercise. All of<br />

those things make me more of a singer now than I was if only<br />

because of that.<br />

AC: We know that folk and country all have roots in Black<br />

music, but they’re not seen as ours today. How do you see your<br />

music in continuity with the wider history of Black music?<br />

JB: Genre has always been a tricky thing for me. I think the<br />

folk / country classification is one of the trickiest because it has<br />

its own implications in terms of who can and who cannot. And<br />

that's always been something, I guess, that's drawn me to it, not<br />

just to sing it, but to really look at what that is. And it's storytelling.<br />

So I never felt an embargo on whether or not I was allowed to<br />

tell a story — that didn't seem so off-limits to me. I think what did<br />

is being called a country artist or being called a folk artist. That<br />

felt like people wanted to keep that away from how they heard my<br />

music. And it's interesting — there are so many Black country<br />

artists that were not classified as country. Ray Charles released<br />

an entire country album. So did Tina Turner. Charlie Pride is one<br />

of the highest-selling artists in the world in country music.<br />

So there were all these things that I was seeing that weren’t<br />

real, that are just a way to make sure there is a space that's<br />

untouched. And I never liked that idea. So in terms of the wider<br />

picture, for Black artists or Black music, there's nothing we've<br />

never touched, or created. And again, I think, part of growing up<br />

in Oakland put some things in terms of intention, and pursuing<br />

things, in perspective for me pretty early on. I think it made it<br />

possible to just focus, to just drown out the noise of what genre is,<br />

which at its worst is musical segregation. Like what you like, play<br />

what you like. That's it.<br />

I will — fortunately, and unfortunately — never experience<br />

my music the way that other people do. So I'm always surprised<br />

with what someone hears when they listen. Because I might<br />

be going for one thing and someone can hear something completely<br />

different. But for my sound, I think that being in love with<br />

musicals, really does sort of speak to some aspect of the ethereality<br />

you mentioned. As a kid, all of my favorite musicals books, and<br />

even movies were all fantasy, and escapist. Even as an adult, I'm<br />

learning I can very easily go into a world and completely detach,<br />

and be somewhere else without realizing until I come back. So<br />

I think, that ability actually makes it easier to not bring certain<br />

realities into the music so that it's a space where you're dreaming.<br />

Because dreaming is as much part of reality for me as anything else.<br />

And I think for most people, you know, life is complex<br />

and difficult at times. I need that dreaming place. So I guess,<br />

other people need it too. And that might be what they're<br />

hearing. So all of the influences, country, folk — I've never been<br />

someone who said no to any genre or avenue of music, because<br />

anything that isn't what I do is interesting to me and makes an<br />

impression. So when I sit down to write, those impressions<br />

come through. I try not to be too invested in that and just know<br />

that I'm the avenue by which the music comes. So whatever is<br />

meant to be in that pot, or the recipe that was meant for that pot<br />

is what’s there. I'm just doing the work of picking up the pen and<br />

the guitar. AC<br />

Listen to Jennah Bell's Anchors & Elephants on Spotify<br />

104 aphrochic issue eight 105