You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

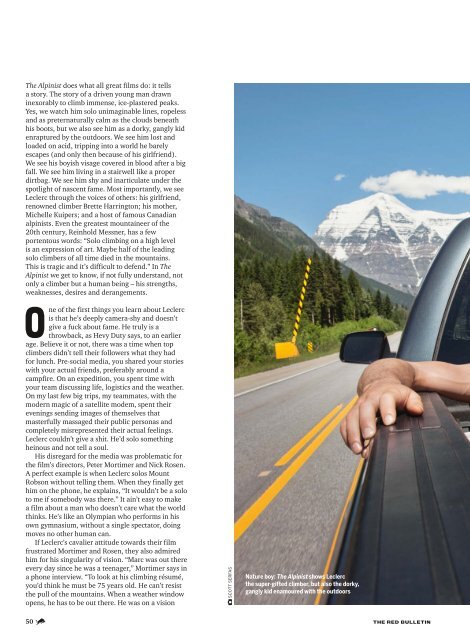

The Alpinist does what all great films do: it tells<br />

a story. The story of a driven young man drawn<br />

inexorably to climb immense, ice-plastered peaks.<br />

Yes, we watch him solo unimaginable lines, ropeless<br />

and as preternaturally calm as the clouds beneath<br />

his boots, but we also see him as a dorky, gangly kid<br />

enraptured by the outdoors. We see him lost and<br />

loaded on acid, tripping into a world he barely<br />

escapes (and only then because of his girlfriend).<br />

We see his boyish visage covered in blood after a big<br />

fall. We see him living in a stairwell like a proper<br />

dirtbag. We see him shy and inarticulate under the<br />

spotlight of nascent fame. Most importantly, we see<br />

Leclerc through the voices of others: his girlfriend,<br />

renowned climber Brette Harrington; his mother,<br />

Michelle Kuipers; and a host of famous Canadian<br />

alpinists. Even the greatest mountaineer of the<br />

20th century, Reinhold Messner, has a few<br />

portentous words: “Solo climbing on a high level<br />

is an expression of art. Maybe half of the leading<br />

solo climbers of all time died in the mountains.<br />

This is tragic and it’s difficult to defend.” In The<br />

Alpinist we get to know, if not fully understand, not<br />

only a climber but a human being – his strengths,<br />

weaknesses, desires and derangements.<br />

One of the first things you learn about Leclerc<br />

is that he’s deeply camera-shy and doesn’t<br />

give a fuck about fame. He truly is a<br />

throwback, as Hevy Duty says, to an earlier<br />

age. Believe it or not, there was a time when top<br />

climbers didn’t tell their followers what they had<br />

for lunch. Pre-social media, you shared your stories<br />

with your actual friends, preferably around a<br />

campfire. On an expedition, you spent time with<br />

your team discussing life, logistics and the weather.<br />

On my last few big trips, my teammates, with the<br />

modern magic of a satellite modem, spent their<br />

evenings sending images of themselves that<br />

masterfully massaged their public personas and<br />

completely misrepresented their actual feelings.<br />

Leclerc couldn’t give a shit. He’d solo something<br />

heinous and not tell a soul.<br />

His disregard for the media was problematic for<br />

the film’s directors, Peter Mortimer and Nick Rosen.<br />

A perfect example is when Leclerc solos Mount<br />

Robson without telling them. When they finally get<br />

him on the phone, he explains, “It wouldn’t be a solo<br />

to me if somebody was there.” It ain’t easy to make<br />

a film about a man who doesn’t care what the world<br />

thinks. He’s like an Olympian who performs in his<br />

own gymnasium, without a single spectator, doing<br />

moves no other human can.<br />

If Leclerc’s cavalier attitude towards their film<br />

frustrated Mortimer and Rosen, they also admired<br />

him for his singularity of vision. “Marc was out there<br />

every day since he was a teenager,” Mortimer says in<br />

a phone interview. “To look at his climbing résumé,<br />

you’d think he must be 75 years old. He can’t resist<br />

the pull of the mountains. When a weather window<br />

opens, he has to be out there. He was on a vision<br />

SCOTT SERFAS<br />

Nature boy: The Alpinist shows Leclerc<br />

the super-gifted climber, but also the dorky,<br />

gangly kid enamoured with the outdoors<br />

50 THE RED BULLETIN