NCC Magazine, Spring 2022

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

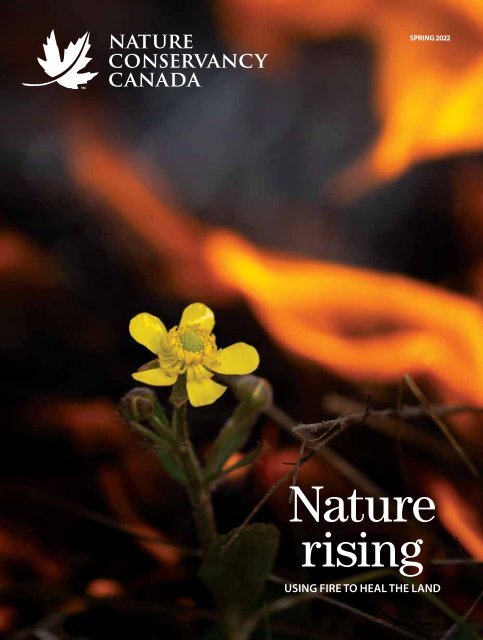

SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

Nature<br />

rising<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

USING FIRE TO HEAL THE LAND<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

WINTER 2021 1

Hastings Wildlife Junction, ON<br />

SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

CONTENTS<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

4 Native plants for<br />

your garden<br />

Gardening with easy-to-grow plants.<br />

6 Pearson Township Wetland<br />

A wondrous wetland on Lake Superior’s<br />

North Shore.<br />

7 Bat signal<br />

How to help Canada’s declining<br />

bat populations.<br />

7 A natural fit<br />

Cataloguing the diversity of those<br />

who explore nature.<br />

8 Prescription to burn<br />

The paradox of fire.<br />

12 Bald eagle<br />

A showstopper of a bird.<br />

14 Wave of change<br />

Dax Dasilva is inspiring others to make<br />

a difference for nature.<br />

16 Project updates<br />

Plains bison re-established; grassland<br />

stewardship; Hastings Wildlife Junction.<br />

18 Hidden in plain sight<br />

The magical, endangered world of lichen.<br />

Digital extras<br />

Check out our online magazine page with<br />

additional content to supplement this issue,<br />

at nccmagazine.ca.<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

245 Eglinton Ave. East, Suite 410 | Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 3J1<br />

magazine@natureconservancy.ca | Phone: 416.932.3202 | Toll-free: 877.231.3552<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) is the country’s unifying force for nature. We seek solutions to the<br />

twin crises of rapid biodiversity loss and climate change through large-scale, permanent land conservation.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is a registered charity. With nature, we build a thriving world.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada <strong>Magazine</strong> is distributed to donors and supporters of <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

TM<br />

Trademarks owned by the Nature Conservancy of Canada.<br />

FSC is not responsible for any calculations on<br />

saving resources by choosing this paper.<br />

Printed on Enviro100 paper, which contains 100% post-consumer fibre, is EcoLogo, Processed Chlorine<br />

Free certified and manufactured in Canada by Rolland using biogas energy. Printed in Canada with vegetablebased<br />

inks by Warrens Waterless Printing. This publication saved 172 trees and 56,656 litres of water*.<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

GENERATED BY: CALCULATEUR.ROLLANDINC.COM. PHOTO: <strong>NCC</strong>. COVER: CHELSEA MARCANTONIO/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

*<br />

natureconservancy.ca

Nature champions<br />

Featured<br />

Contributors<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: PHOTO COURTESY OF DAWN CARR. CHEYENNE RAE; LUCY LU.<br />

Kootenay River Ranch<br />

Conservation Area, BC<br />

If there is one thing I’ve noticed since joining the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) family in 2021, it’s the<br />

unwavering determination demonstrated by colleagues,<br />

partners and supporters to be champions for nature. I have<br />

found respite among caring, talented and passionate people who<br />

are working every day to make a tangible difference and positive<br />

contribution — locally, nationally and globally. I have also come<br />

to learn that <strong>NCC</strong>’s determination for nature’s sake is grounded<br />

in a deeply held belief that conservation action is a remedy to<br />

our world’s most pressing challenges. Conserving nature for the<br />

greater good is good medicine for all.<br />

As we collectively face the twin crises of biodiversity loss<br />

and climate change, there is growing recognition that Canadians<br />

need to share responsibility not only for conserving, but for<br />

caring for our natural areas for the long term.<br />

Last June, on World Environment Day, the United Nations<br />

kicked off the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030).<br />

The goal of this global movement is to “prevent, halt and reverse<br />

the degradation of ecosystems on every continent and in every<br />

ocean.” It could not have come at a more critical time, as humans<br />

have modified 77 per cent of terrestrial land (excluding<br />

Antarctica) and 87 per cent of oceans, globally. In this issue,<br />

you’ll read about the dramatic impact that fire can have in managing<br />

and restoring natural areas.<br />

As Canada embraces its global commitment to conserve<br />

nature by protecting 30 per cent of its lands and waters by 2030,<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is in position to accelerate conservation. It’s so great to be<br />

part of a team who values and delivers conservation action for<br />

communities, with far-reaching benefits.<br />

Yours in nature,<br />

Dawn Carr<br />

Dawn Carr<br />

Director, strategic conservation, <strong>NCC</strong><br />

Susan Peters is a<br />

Winnipeg-based writer<br />

and editor. She wrote<br />

“Prescription to burn,”<br />

page 8, and her articles<br />

have appeared in<br />

Canadian Geographic,<br />

Report on Business and<br />

The Walrus.<br />

Lucy Lu is a freelance<br />

photographer whose<br />

work explores cultural<br />

identity, personal<br />

histories, and collective<br />

myths and memories.<br />

She photographed<br />

Micheline Khan for<br />

“A natural fit,” page 7.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2022</strong> 3

COAST TO<br />

COAST<br />

Native plants<br />

for your<br />

garden<br />

Beautify your garden and help local biodiversity with easyto-grow<br />

native plants suggested by our regional experts<br />

From coast to coast, frosty, hard ground is giving way to the green-up<br />

unfurling across the country. What better way to welcome the change of<br />

seasons than by preparing your planting space so you can look forward to<br />

a thriving garden? Whether you’re starting from scratch or expanding your<br />

gardening efforts, adding easy-to-grow native plants not only beautifies your<br />

yard or balcony, it also benefits your local ecosystem. Gardening is also a great<br />

opportunity to breathe in fresh air, move your body, focus on the physical<br />

environment and even see some wildlife.<br />

Before you plant, ask your local native plant nursery or regional native plant<br />

society for guidance on whether your plant choices are truly local to you.<br />

CHRISTOPHER PRICE / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO.<br />

4 SPRING <strong>2022</strong> natureconservancy.ca

IRINA NAOUMOVA / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; ISTOCK; WIRESTOCK, INC. / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; CHRISTOPHER PRICE / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; AGEFOTOSTOCK / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; DON JOHNSTON_PL / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO.<br />

Berryproducing<br />

plants<br />

Winter currant<br />

BC<br />

Winter currant is a deciduous<br />

shrub that does best in moist,<br />

well-drained soil. Native to BC’s<br />

south coast, this plant thrives in<br />

a sunny spot, but does tolerate<br />

some shade. Its drooping clusters<br />

of pink flowers attract butterflies,<br />

hummingbirds, songbirds and<br />

bees. The plant produces edible<br />

blue-black berries that are great<br />

for jams, syrups and pies.<br />

Canadian buffaloberry<br />

AB, BC, MB, NB, NL, NS, NT,<br />

NU, ON, QC, SK, YT<br />

Canadian buffaloberry is a native<br />

deciduous shrub found throughout<br />

North America, including<br />

the boreal forest, aspen parkland<br />

foothills and grassland regions.<br />

This hardy, medium-sized shrub<br />

(1–3 metres tall) will tolerate<br />

poor soil conditions. It produces<br />

attractive, edible — though<br />

bitter — red fruit, which is also<br />

a food source for small mammals<br />

and birds.<br />

Ground<br />

cover<br />

Canada anemone<br />

AB, BC, MB, NB, NL, NS, NT,<br />

NU, ON, PE, QC, SK<br />

Canada anemone is a<br />

low-maintenance perennial forb<br />

that produces cup-shaped white<br />

flowers. It grows in cool and<br />

humid woodlands and cool moist<br />

prairies, but can tolerate a variety<br />

of other types of soils. It makes<br />

a nice ground cover on its own or<br />

among milkweeds and between<br />

shrubs, but can spread in gardens<br />

and create full ground cover.<br />

Canada anemone attracts bees<br />

and other pollinators, as well as<br />

predatory wasps, which control<br />

common insect pests.<br />

Ostrich fern<br />

AB, BC, MB, NB, NL, NS, NT,<br />

ON, PE, QC, SK, YT<br />

Ostrich fern does best in moist,<br />

relatively rich sites, full sun or full<br />

shade, but may spread aggressively.<br />

This plant will grow under the<br />

dense, maple-heavy canopies<br />

of urban backyards or in rain<br />

gardens. It can be planted as<br />

borders by streams or ponds.<br />

Young fronds can be harvested<br />

and eaten, if cooked properly,<br />

before they unfurl; the taste is<br />

comparable to asparagus.<br />

Beautiful<br />

blooms<br />

Great blanket-flower<br />

AB, BC, MB, SK<br />

In the mixed grassland region,<br />

great blanket-flower is a<br />

herbaceous perennial that<br />

tolerates well-drained, nutrient-poor<br />

soil. It blooms all<br />

summer, with flowers that<br />

last a long time. It is easy to find<br />

the native variety (as seeds and<br />

plants) in local nurseries. Both<br />

bees and butterflies (and other<br />

pollinators) use this plant. The<br />

entire plant is covered in fuzzy<br />

hairs, which can be an irritant<br />

for some people.<br />

White turtlehead<br />

MB, NB, NL, NS, ON, PE, QC<br />

White turtlehead is found in wet<br />

locations in the wild, but adapts<br />

well to average garden soils if<br />

kept watered. The species grows<br />

in partial sun, and moist to wet<br />

gardens, and blooms from late<br />

summer to fall. Plants divide and<br />

transplant readily, and once<br />

established are virtually troublefree.<br />

They are a good late-season<br />

nectar source for pollinators and<br />

the primary host plant for<br />

Baltimore checkerspot butterfly.<br />

Shrubs<br />

Choke cherry<br />

AB, BC, MB, NB, NL, NS, NT,<br />

ON, PE, QC, SK<br />

Choke cherry is a shrub that<br />

can grow up to six metres tall.<br />

It produces clusters of red<br />

cherries that are very sour but<br />

edible. Choke cherry does best<br />

in rich, well-drained soil and can<br />

grow under light shade to full<br />

sun. The fruits are a preferred<br />

food source for a variety of birds,<br />

including pileated woodpecker,<br />

eastern bluebird and cedar<br />

waxwing. Mammals, such as red<br />

fox, skunk and chipmunk, may<br />

also browse the twigs and buds<br />

for food. This plant is resistant<br />

to salt and can be planted along<br />

shorelines or roadsides.<br />

Oblong-leaf<br />

serviceberry<br />

NB, NS, PE, QC<br />

Oblong-leaf serviceberry,<br />

also known as chuckleberry,<br />

is a deciduous shrub with<br />

edible dark-purple berries. It’s<br />

an excellent early flower for<br />

pollinators. Many bird species<br />

feed on its berries, as they are an<br />

important food source before<br />

migration. This shrub grows well<br />

in a variety of conditions and is<br />

resistant to air pollution.<br />

BEST TIME TO GET PLANTS IN THE GROUND<br />

A general rule of thumb is to wait until after the last frost to plant native flowers and grasses. In some parts of<br />

the country, this can be as early as April, while in other areas it may be late May. If you’re starting from seed,<br />

some native species require a cold–moist stratification (when seeds go through a period of cold temperatures)<br />

to break the seed’s dormancy. You can mimic these conditions at home using moist, sterile substrate (such as<br />

perlite) in a sealed bag in the refrigerator (ideally a few weeks before the last frost).<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2022</strong> 5

BOOTS ON<br />

THE TRAIL<br />

<strong>NCC</strong><br />

Nature Reserve<br />

P<br />

★<br />

Pearson Township Wetland<br />

Conservation Reserve<br />

Hwy 597<br />

<br />

N<br />

★<br />

★<br />

<strong>NCC</strong><br />

Nature Reserve<br />

<strong>NCC</strong><br />

Nature Reserve<br />

Chestnut-sided warbler<br />

★<br />

Roundleaf sundew<br />

Starflower<br />

North American river otter<br />

<br />

N<br />

Beaver<br />

Pearson Township<br />

Wetland<br />

A wondrous wetland on Lake Superior’s North Shore<br />

The Pearson Township Wetland, located within<br />

the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s (<strong>NCC</strong>’s) Lake<br />

Superior Coast Natural Area in Neebing, Ontario,<br />

measures 739 hectares. Much of it is protected as<br />

a conservation area, including 130 hectares by <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

Volunteers contributed over 150 hours to clear<br />

the trails and install signage. The six-kilometre<br />

Pearson Township Wetland Nature Trail is located<br />

on Crown land, and overlooks <strong>NCC</strong>’s Pearson<br />

Township Wetland Nature Reserve.<br />

Located in the headwaters of the Pine River, this<br />

large wetland provides critical habitat for a variety<br />

of wildlife, such as American river otter and beaver.<br />

Back in the mid-1990s, Gary Davies, now retired<br />

from his position as <strong>NCC</strong>’s program director for<br />

northwestern Ontario, dreamed of creating a trail<br />

that overlooked the Provincially Significant Wetland.<br />

The goal was to create an enjoyable and educational<br />

experience for visitors.<br />

Thanks to the generous contributions of volunteers<br />

and donors, Davies’ vision became a reality.<br />

The trail climbs from the parking area to a loop<br />

atop the mesa, with stunning views overlooking<br />

the wetland. The trail is steep in sections, ranging<br />

in difficulty from moderate to difficult.<br />

STAY SAFE<br />

Please stay safe and respect local health directives<br />

when visiting <strong>NCC</strong> properties.1<br />

LEARN MORE<br />

natureconservancy.ca/pearsonwetland<br />

LEGEND<br />

-- Trail<br />

★ Lookout<br />

P Parking<br />

SPECIES TO SPOT<br />

• American redstart<br />

• black bear<br />

• chestnut-sided<br />

warbler<br />

• fisher<br />

• ghost pipe<br />

• magnolia warbler<br />

• moose<br />

• North American<br />

river otter<br />

MAP: JACQUES PERRAULT. PHOTOS: ROBERT MCCAW.<br />

6 SPRING <strong>2022</strong> natureconservancy.ca

ACTIVITY<br />

CORNER<br />

BACKPACK<br />

ESSENTIALS<br />

Be batty<br />

Shine the bat signal and do<br />

your part to help Canada’s<br />

declining bat populations<br />

PHOTO: LUCY LU. ILLUSTRATION: BELLE WUTHRICH.<br />

Bats may be commonly associated with a certain<br />

superhero, but these often-misunderstood<br />

mammals are facing many threats, including<br />

habitat loss and a fast-spreading fungal disease<br />

called white-nose syndrome.<br />

Here are a few things you can do to help bats<br />

(find out more at natureconservancy.ca/bats):<br />

1. Build and install a bat box near your<br />

home, with just a few tools and some easy-tosource<br />

materials.<br />

2. Become a bat watcher by converting your<br />

smartphone into a bat detector.<br />

3. If you have to remove bats from your<br />

house, use humane practices and/or keep<br />

them from re-entering your home.<br />

4. Find out more about the bat species in your<br />

neighbourhood, and your share your story on<br />

social media with the hashtag #MySmallAct.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is protecting habitat for bats across Canada.<br />

We are also monitoring bat populations on our<br />

properties, and working with the Toronto Zoo<br />

on their Native Bat Conservation Program.<br />

Find out more about these small acts and<br />

how you can help bats in your neighbourhood<br />

at natureconservancy.ca/bats.<br />

A natural fit<br />

Ecologist Micheline Khan catalogues the sights of nature<br />

and the diversity of those who explore it<br />

Ihave always been fascinated by nature. I would venture into the woods near my<br />

childhood home, teeming with life, reeds tall and stately and standing guard<br />

over marshy ponds, salamanders creeping under dark, dank rocks as songbirds<br />

soared and dipped with an exhilarating freedom. It was natural that I would become<br />

an ecologist, that I would make a space for myself where there were few<br />

others who looked like me. I remember the first time I did field work in Algonquin<br />

Park, I all but forced two graduate researchers to let me volunteer with them. The<br />

curious, sometimes derisive stares when we went into town did nothing to dampen<br />

my resolve. I didn’t quite fit the mold, to some. The researchers, however, recognized<br />

a kindred spirit and welcomed me into their homes. As we ventured out into<br />

the forests and onto the lakes with our canoes, I began to appreciate and be in awe<br />

of how tremendously vast these spaces were.<br />

My goal then and there was to make nature more accessible to underserved<br />

communities so that they know they deserve access to these spaces too. There is<br />

beauty here, undiscovered, underappreciated, in hard-to-find nooks and crannies.<br />

So, my backpack carries an old Fujifilm camera my dad gifted me; what I need to<br />

capture and convey not only the sights of nature but the diverse people who work<br />

in and explore it. I catalogue us so that younger generations will know they<br />

belong here too.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2022</strong> 7

Prescription<br />

burn<br />

to<br />

The paradox of fire: How something so<br />

destructive can benefit the landscape<br />

BY Susan Peters<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

CHELSEA MARCANTONIO/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

8 SPRING <strong>2022</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Fire has been used to manage the<br />

landscape for thousands of years.<br />

Standing over the flames with<br />

shovels and backpack sprayers of water,<br />

ready to stamp out stray embers, the burn<br />

crew watches the fire they’ve set. “Especially<br />

when it’s a boring burn, it’s fun,” says Julie<br />

Sveinson Pelc, the incident commander in charge of the<br />

fire. “Boring means we’re standing and looking at fire. It<br />

means things are going exactly as they should,” she explains<br />

as, during a COVID-19 surge in the height of winter,<br />

she shows photos of a planned burn that happened last<br />

September at the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve in southeastern<br />

Manitoba, where the scent of burning grasses can<br />

resemble essential oils.<br />

Although North America has a recent history of fire<br />

suppression, fire was used to manage landscapes for thousands<br />

of years prior to European settlement. For several<br />

decades, Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) staff have<br />

been bringing back fire in an intentional way to manage<br />

the organization’s conservation lands, from BC to Saskatchewan<br />

and Manitoba, and even the grasslands of Ontario.<br />

Particularly in prairie regions, the plants and animals<br />

we have today — and the ones we want for tomorrow, too<br />

— evolved to thrive in an ecosystem that experienced<br />

regular disturbances, such as grazing, burning, flooding<br />

and drought.<br />

With 20 years of burn experience, Pelc, who manages<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s stewardship program in Manitoba, can debate the<br />

merits of a light, surface burn versus a high-intensity fire:<br />

“It can boil the trees: you can see the fluids bubbling.”<br />

The fire was intended to contribute to the ongoing restoration<br />

of a 20-hectare area of grassland that is prime habitat<br />

for endangered monarch butterflies. It removed willows<br />

and other woody shrubs that were growing in the<br />

grasses and that would turn the wide, open land into a<br />

woods of aspen and bur oak, if left unchecked. Fires burn<br />

dry grasses and leaves, returning those nutrients to the<br />

soil and leaving the earth open for rain to sink in. Burning<br />

the area that had previously been seeded will grow more<br />

of the plants that feed monarch butterfly caterpillars<br />

and adults.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2022</strong> 9

Clockwise from left: Julie Sveinson Pelc communicating<br />

prescribed fire activity with the crew at the Tall Grass Prairie<br />

Preserve; fire crew members overseeing burn; Rice Lake Plains.<br />

These fires are set with a “prescription” to<br />

burn, meaning professionally managed, intentionally<br />

set fires that burn in a pre-determined<br />

area, under strictly controlled circumstances<br />

for the sole purpose of restoring natural habitat<br />

(a different kind of burn happens in agriculture<br />

when farmers burn crop stubble after<br />

harvest). Planning for prescribed burns involves<br />

consulting a decision-making tool<br />

called the Multiple Species at Risk Recovery,<br />

Management and Research (Multi-SAR) plan<br />

to determine the best time of year to burn to<br />

support a species, such as endangered prairie<br />

white-fringed orchids or Poweshiek skipperling<br />

butterflies. It means assessing the dryness<br />

on the ground, relative humidity, wind<br />

and temperature, getting burn permits from<br />

the municipality or province, and doing outreach<br />

to fire departments and neighbours who<br />

might have concerns that an out-of-control<br />

fire could destroy their homes or ranches.<br />

When <strong>NCC</strong> undertakes prescribed burns,<br />

they’re usually done to decrease dry plant<br />

litter build-up and prevent woody tree species<br />

from overtaking a prairie or grassy area,<br />

as at the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve, although<br />

there are also plans to use fire to clear the<br />

understory in open forests like those at the<br />

Darkwoods Conservation Area in BC. Across<br />

North America, controlled burns are managed<br />

by federal and provincial parks services,<br />

Indigenous communities and municipalities,<br />

sometimes to prevent out-of-control forest<br />

fires. “When fuel loads build up, the fires can<br />

be hotter, cover bigger areas — it can be<br />

devastating. Some groups burn to avoid the<br />

risk of catastrophic fire, to make sure humans<br />

aren’t at risk,” says Sam Knight, <strong>NCC</strong>’s Weston<br />

Family Science Program manager, and<br />

also a conservation biologist who manages the<br />

organization’s national conservation research<br />

program. “A lot of ecosystems are adapted to<br />

fire and need disturbances, like grazing and<br />

fire, to be maintained.”<br />

Under control<br />

The September burn in Manitoba saw the<br />

crew of 10 workers on a mowed fire guard of<br />

grass in a large square lay a trail of water<br />

along the fire lines. They then used specialized<br />

drip torches to light the burn line, creating<br />

a triple line of defense against a fire escaping<br />

their control. “People like to brag about<br />

how straight their burn lines are,” Pelc shrugs,<br />

but she’s proud of how the crew of new and<br />

experienced <strong>NCC</strong> staff in personal protective<br />

equipment, such as leather boots and gloves,<br />

fire suits, masks and safety glasses, moves in<br />

slow and unhurried cooperation to complete<br />

the backing burn line against the wind, before<br />

the head fire is lit with the wind to dramatically<br />

sweep across the centre of the section.<br />

A lifelong Manitoban, Pelc’s first fire happened<br />

at the preserve when she was a master’s student<br />

in botany who volunteered to look out<br />

for embers that crossed the fire guard. She<br />

now burns there professionally and at two<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> properties in Manitoba within the mixedgrass<br />

prairie: Yellow Quill and Fort Ellice.<br />

Farther east, prescribed burns have been<br />

happening for the past decade near Peterborough,<br />

Ontario, at the Rice Lake Plains Natural<br />

Area. The tall grass prairie and black oak<br />

savannah in the area are managed in partnership<br />

with other conservation organizations,<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: <strong>NCC</strong>; CHELSEA MARCANTONIO/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; CHELSEA MARCANTONIO/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

10 SPRING <strong>2022</strong> natureconservancy.ca

LEFT TO RIGHT: <strong>NCC</strong>; CHELSEA MARCANTONIO/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

including Alderville First Nation. The Alderville<br />

black oak savannah is “true remnant<br />

prairie,” according to Val Deziel, coordinator<br />

of conservation biology in Ontario for <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

“In the last 10 years, we’ve focused our efforts<br />

in the area on not only conservation, but<br />

the restoration of land,” says Deziel, whose<br />

work includes supervising fires run by a private<br />

contractor. Thinning trees with a chainsaw,<br />

along with prescribed burns, helps to<br />

keep grasslands open. “Woodpeckers love the<br />

burns — if there’s a tree that’s half dying and<br />

full of insects, like an old pine, the birds will<br />

fly in and get fat on the insects after the fire<br />

finishes off the tree,” says Deziel. She grew<br />

up in the area and can tell you how, before<br />

colonization, people conducted burns to grow<br />

medicinal plants along with lush, green grass<br />

to attract grazing animals for hunters. As we<br />

enter the second year of the UN Decade on<br />

Restoration (2021–2030), fire is a dramatic<br />

example of how we can play a role in managing<br />

and healing nature for the long term.<br />

Another place where controlled burns<br />

are occurring on <strong>NCC</strong> lands is in BC. At the<br />

Cowichan Garry Oak Preserve on Vancouver<br />

Island, prescribed burns in these Garry oak<br />

meadows not only lower the risk of wildfires,<br />

but also control invasive plants and promote<br />

the growth of fire-adapted native species.<br />

The timing of when fires should be prescribed<br />

remains an important decision for <strong>NCC</strong> in BC,<br />

where dry summers increase the risk of extreme<br />

wildfires. Burns take place in autumn<br />

when wildfire risk is low. When burns do take<br />

place at the Cowichan Garry Oak Preserve,<br />

they are often low-intensity fires, which don’t<br />

burn very hot. “Five minutes after the fire<br />

passes, the ground is cool enough to touch,”<br />

says Ginny Hudson, manager of conservation<br />

planning and stewardship for <strong>NCC</strong> in BC.<br />

These types of meadows have been traditionally<br />

managed with fire by Indigenous people<br />

for thousands of years. One purpose for the<br />

burns here is to promote the growth of cultural<br />

food plants like camas, which have sweet<br />

tasting roots that can be baked or dried.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s goal is to work more closely with local<br />

Indigenous people on burns, as happens at<br />

Rice Lake Plains in Ontario.<br />

Medicine for the land<br />

Around the world and within North America,<br />

fires are part of how many Indigenous<br />

Peoples manage the landscape. Amy Cardinal<br />

Christianson is a fire social scientist with Canadian<br />

Forest Service, a co-host of the podcast<br />

Good Fire and a Métis woman. She has also<br />

authored Blazing the Trail: Celebrating Indigenous<br />

Fire Stewardship. “When settlers<br />

came to Canada, they brought a European<br />

idea of forest management. The idea was to<br />

protect timber. They saw fire as a risk to forests.”<br />

Christianson distinguishes between<br />

cultural burns — low-intensity, slow burns<br />

on a small piece of land for cultural reasons,<br />

which she calls ”medicine for the land” — and<br />

prescribed burns, which she describes as<br />

usually hot, high-intensity burns that cover<br />

large areas to reduce fuel or to clear land for<br />

ecological reasons. Christianson says barriers,<br />

such as the training and certification required,<br />

don’t recognize Indigenous ways of knowing.<br />

She would like to see more Indigenous people<br />

involved and more local autonomy in burning<br />

decisions. “Over the next 10 years, hopefully<br />

the communities and wildfire management<br />

agencies can work together,” she adds.<br />

Meanwhile, at the September burn at the<br />

Tall Grass Prairie Preserve, the result could<br />

be seen the next day. Pelc describes islands<br />

of intact grass left behind in a black ocean of<br />

soot, where the patches of native grasses will<br />

regrow from their roots, newly reinvigorated.<br />

“As the leader, I find a burn somewhat intense,<br />

but I find it rewarding after it’s finished,” says<br />

Pelc. The local fire chief stopped by and<br />

checked out the new two-way radios that the<br />

burn crew had purchased on his recommendation,<br />

while neighbours slowed down to<br />

wave as they drove past. In 2021, Pelc led the<br />

crew on eight prescribed fires that covered<br />

167 hectares, the most in the last 10 years<br />

that <strong>NCC</strong> has burned in Manitoba. Pelc is already<br />

planning for spring: after the fire crew<br />

renew their training, as soon as the snow<br />

melts, it’s dry enough and the wind is low,<br />

Fort Ellice is due for a good burn.1<br />

As we enter the second year of the<br />

UN Decade on Restoration (2021–2030),<br />

fire is a dramatic example of how<br />

we can play a role in managing and<br />

healing nature for the long term<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2022</strong> 11

SPECIES<br />

PROFILE<br />

Bald eagle<br />

With a wingspan of more than two metres, this regal bird is a showstopper<br />

JUNIORS BILDARCHIV GMBH / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO.<br />

12 SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

APPEARANCE<br />

This bird is far from bald; it derives its name<br />

from the word “piebald,” meaning “patches of two<br />

different colours,” in reference to the eagle’s white head<br />

and tail, and dark brown body.<br />

Spanning more than two metres, a bald eagle’s wings<br />

are made for soaring. This species can measure about<br />

76 centimetres in height and weigh three to seven kilograms.<br />

Female bald eagles are typically larger than males.<br />

Bald eagles feast on the Squamish River<br />

Plumage on male and female bald eagles is identical.<br />

Adults have a dark brown body with white feathers<br />

on their head and tail. Their beaks are yellow, as are their<br />

legs. Juvenile bald eagles have mostly dark heads and<br />

tails, and are often mistaken for turkey vultures or<br />

golden eagles. It takes four to five years for<br />

them to reach adult colouration.<br />

RANGE<br />

Bald eagles are distributed from<br />

coast to coast, ranging from Canada’s<br />

boreal forest to northern Mexico, a range of<br />

approximately 2.5 million square kilometres.<br />

Much of Canada’s bald eagle population lives in<br />

coastal British Columbia, with inland populations<br />

found in boreal forests across the country, as well as<br />

populations in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.<br />

Bald eagles rely on forested areas close to lakes,<br />

rivers, marshes and coastal habitats. In<br />

winter, bald eagles can be found in<br />

parts of southern Canada.<br />

What <strong>NCC</strong> is doing<br />

to protect habitat for<br />

this species<br />

Since the 1990s, <strong>NCC</strong> has been at<br />

the forefront of efforts to protect<br />

core habitat for the largest recorded<br />

concentration of wintering bald<br />

eagles in North America. In the small<br />

community of Brackendale, BC, just<br />

north of Vancouver, bald eagles congregate<br />

by the thousands from November<br />

to March to feast on the abundant<br />

salmon spawning in the Squamish and<br />

Cheakamus rivers. In partnership with<br />

the Cheakamus Centre, an outdoor<br />

environmental education centre, <strong>NCC</strong><br />

placed a conservation agreement on<br />

the centre’s 170-hectare property along<br />

the Cheakamus River, ensuring protection<br />

of its old-growth forest and salmon-rich<br />

riverfront in perpetuity.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> also participated in a campaign<br />

to educate the public about how<br />

to respectfully view the eagles of<br />

Brackendale, which included the<br />

construction of a viewing shelter and<br />

interpretive signs. The Eagle Count is<br />

a popular event, dating back to at least<br />

1986, when the community gathers in<br />

January to watch the birds.1<br />

THREATS<br />

PHOTO: GUNTER MARX / WI / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO. ILLUSTRATIONS: CORY PROULX.<br />

Bald eagles are currently not listed as<br />

an at-risk species and have healthy<br />

populations throughout most of their range,<br />

but this was not always the case. Historically,<br />

the species declined as a result of habitat loss and<br />

unintentional DDT poisoning. Public education,<br />

habitat conservation and regulations have helped<br />

bald eagle populations recover. Today, researchers,<br />

conservation groups and community<br />

science programs continue to monitor<br />

these impressive birds.<br />

HELP OUT<br />

Help protect habitat<br />

for species at risk at<br />

giftsofnature.ca.<br />

HABITAT<br />

Bald eagles breed in forested<br />

areas near large bodies of water, such<br />

as ocean coasts and lakeshores. They<br />

prefer tall, mature trees for perching;<br />

this provides them with a wide view of<br />

their surroundings.<br />

In winter, bald eagles can be found<br />

in areas with open water for fishing,<br />

as fish constitute the majority of<br />

their diet.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2022</strong> 13

FORCE FOR<br />

NATURE<br />

Wave<br />

of change<br />

Dax Dasilva, founder of e-commerce platform Lightspeed,<br />

is inspiring others to make a difference for nature<br />

GUILLAUME SIMONEAU.<br />

14 SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

Five minutes from Dax Dasilva’s office in Quebec<br />

flows a natural treasure that nurtures life as big as<br />

humpbacks and as small as tiny krill. It’s also a major<br />

throughway for wildlife and humans that, perhaps, not enough<br />

people have appreciation for: the St. Lawrence River.<br />

“Nature is a big part of my life. It always reminds me of how precious<br />

and vulnerable it is to humanity’s never-ending expansion,” says Dax<br />

Dasilva, founder of e-commerce platform Lightspeed and the non-profit<br />

environmental alliance Age of Union. He attributes his deep connection<br />

to nature to his upbringing on the West Coast, where he had access to<br />

beautiful landscapes. But no matter where he has travelled and settled,<br />

hiking and adventuring have always been a part of his lifestyle.<br />

“Given my early exposure to nature, I felt that when I had the resources<br />

and platform, I would be doing as much as I could to further<br />

conservation,” says Dasilva. “I think people look to tech leaders and<br />

how they approach challenges like humanity’s impact on the future.<br />

For me, there’s no more important way [to be a leader] than by protecting<br />

our planet and its species.”<br />

This vision for safeguarding nature motivated Dasilva to form Age<br />

of Union, a non-profit alliance that supports those working to protect<br />

our planet’s threatened species and ecosystems. He is now on a path<br />

to support tangible conservation projects in his province and around<br />

the world through contributions from like-minded business leaders<br />

and conservation organizations.<br />

If we see positive examples that we can<br />

relate to, where we’re moving the needle,<br />

we will feel the goal is within reach. We<br />

can make impacts every day.<br />

SUPPORTING CONSERVATION ALONG THE<br />

ST. LAWRENCE RIVER<br />

The St. Lawrence River is one of the world’s largest freshwater reserves.<br />

It flows into the St. Lawrence Estuary where fresh water and salt water<br />

meet, eventually emptying into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, which opens<br />

to the Atlantic Ocean. Its entire length (1,197 kilometres) teems with<br />

life that remains productive all year long. Dasilva saw this majestic river<br />

up close during site visits with the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>’s) Joël Bonin, associate regional vice president in Quebec.<br />

“Just an hour away from Montreal, you have the floodplains of<br />

the St. Lawrence, which look like the Florida Everglades. When we<br />

documented all the wildlife close to where [people] live, it is incredibly<br />

humbling. Seeing this first-hand motivates you to do everything you<br />

can to safeguard life here,” explains Dasilva.<br />

As Bonin and Dasilva threaded a boat through the small channels<br />

of the St. Lawrence River delta on a recent visit, they observed the<br />

interconnected life along its shorelines, islands and wetlands. Fish<br />

here rely on river bottoms for spawning. These areas can be at risk<br />

from deforested floodplains, whose exposed soil can get dragged into<br />

the freshwater ecosystem during natural cycles of flooding. The health<br />

of the wetlands along the river is also vital to maintaining nature’s<br />

filtration system, sustaining both humans and wildlife.<br />

Protecting these waters and lands requires<br />

a collective effort, or union, as Dasilva<br />

calls it. This is where Age of Union can<br />

contribute to <strong>NCC</strong>’s work in protecting these<br />

habitats, by supporting restoration activities,<br />

cleaning shorelines, reforesting flood plains<br />

and more.<br />

With support from the alliance, <strong>NCC</strong> has<br />

helped protect more than 205 hectares, restored<br />

over 15 hectares, completed planting<br />

over 1,700 plants and helped recover 32 species<br />

at risk. This included restoration work<br />

on the sandbars of Barachois-de-Malbaie,<br />

where vegetation was planted to reduce natural<br />

erosion and restore degraded areas.<br />

Phragmites control is also well underway at<br />

Île aux Grues, approximately 80 kilometres<br />

from Quebec City, with a plan to halt this<br />

invasive reed’s spread on the island.<br />

The alliance’s funding also contributed<br />

to the protection of over 200 hectares at<br />

the western end of the Montreal Green Belt,<br />

with 1.6 kilometres of shoreline on Rivierè<br />

du Nord: habitat for at-risk northern map<br />

turtles (one of 17 at-risk species protected<br />

through this new acquisition).<br />

“It’s time to shift from going about your<br />

day-to-day life on autopilot to a mindset<br />

that centres around sharing the planet. We<br />

have to think about ourselves as guardians<br />

instead of consumers,” reflects Dasilva.<br />

When asked about his thoughts on inspiring<br />

others, Dasilva says: “Doom and gloom is not<br />

going to motivate people. If we see positive<br />

examples that we can relate to, where we’re<br />

moving the needle, we will feel the goal is<br />

within reach. We can make impacts every<br />

day. Everyone has a unique ability to do<br />

something positive for nature — we can<br />

be changemakers.”<br />

This power of union — with people, and<br />

with nature — is what will motivate positive<br />

change in an age of climate emergency. Business<br />

leaders like Dasilva are hoping that by<br />

showcasing action-oriented causes and their<br />

impacts, sharing people’s stories and leveraging<br />

partnerships, more changemakers will<br />

start their own small actions for nature.<br />

“I’m hoping others will find projects<br />

they feel close to and follow our example,”<br />

Dasilva says confidently.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2022</strong> 15

PROJECT<br />

UPDATES<br />

1<br />

Plains bison herd successfully<br />

re-established to The Key First Nation<br />

SASKATCHEWAN<br />

1<br />

2<br />

THANK YOU!<br />

Your support has made these<br />

projects possible. Learn more at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/where-we-work.<br />

3<br />

Mashkode-bizhiki/plains bison are an iconic symbol of the<br />

grasslands. Indigenous people in North America subsisted<br />

on bison for thousands of years, but European colonization<br />

swiftly drove the bison populations to near extinction through<br />

unsustainable hunting pressure.<br />

Recently, a total of 20 plains bison from Grasslands National Park<br />

and 20 from Old Man on His Back Prairie and Heritage Conservation<br />

Area (OMB) in Saskatchewan were successfully translocated to The<br />

Key First Nation’s (TKFN’s) lands in Treaty 4. With this transfer of<br />

bison, TKFN, Parks Canada and <strong>NCC</strong> are working in collaboration toward<br />

the survival and well-being of these iconic and majestic animals.<br />

The return of mashkode-bizhiki to TKFN advances Indigenous-led<br />

conservation in this area, including managing the herd through Indigenous<br />

ecological knowledge, creating and strengthening relationships between<br />

Nations and stakeholders, and sustaining cultural and socio-economic<br />

opportunities for Indigenous community members.<br />

Chris Gareau, councillor with TKFN and a member of the <strong>NCC</strong><br />

Indigenous Advisory Group in Saskatchewan, noted: “The return of<br />

Bison to TKFN has fostered unity within the community and, most<br />

importantly, an atmosphere for healing, [with] the unlimited benefits<br />

shared by all. Our ancestors relied heavily on Bison for their survival<br />

and well-being, utilizing every part of the Bison for food, clothing,<br />

shelters, tools, implements and in a variety of ceremonies.”<br />

Restoring threatened species to Indigenous Nations is an important<br />

step on the pathway toward Reconciliation. This February, the Honourable<br />

Steven Guilbeault, minister of environment and climate change<br />

and minister responsible for Parks Canada, and Jennifer McKillop, Saskatchewan<br />

regional vice-president for <strong>NCC</strong>, were present at a celebration<br />

of the translocation of the 40 plains bison to establish a new herd<br />

with TKFN.<br />

MARK TAYLOR; INSET: PARKS CANADA.<br />

The recovery of mashkode-bizhiki/plains bison to Indigenous Nations<br />

is an important step on the pathway toward Reconciliation.<br />

16 SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

Marsh Ranch, Alberta<br />

Wild + Pine staff<br />

tree planting on<br />

prepped site.<br />

2<br />

Grassland stewardship keeping the prairie healthy<br />

THE PRAIRIES<br />

Partner Spotlight<br />

L TO R: CARYS RICHARDS/<strong>NCC</strong>; <strong>NCC</strong>; MAIDA TANWEER.<br />

A new collaboration, the largest ever in support of grassland stewardship in Canada’s Prairie provinces, aims<br />

to care for unique and threatened grassland ecosystems in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Home to<br />

rare and endangered plant and animal species, grasslands sequester carbon, filter water and stabilize soil.<br />

Over the next few years, <strong>NCC</strong>, in cooperation with four land trusts in Canada's prairies, will administer<br />

the Stewardship Investment Program, part of the Weston Family Prairie Grasslands Initiative.<br />

The program, launched in June 2021, will impact the plant and wildlife biodiversity of up to 1.4 million<br />

hectares of grasslands, through the delivery of up to 800 individual grants. Livestock producers with<br />

conservation agreements with <strong>NCC</strong>, community pastures, and individuals renting lands from <strong>NCC</strong> and<br />

other land trusts can apply for funding to implement a range of projects that support the conservation<br />

of biodiversity on rangelands, from installing wildlife-friendly fencing to installing solar powered remote<br />

watering systems.<br />

Empowering ranchers — the primary owners and managers of the remaining grasslands — with stewardship<br />

tools, incentives, education and support will encourage the adoption of management practices<br />

that support biodiversity. Improving the use and productivity of grasslands will ensure that all its inhabitants<br />

are sustained, and can reduce the risk of further grassland loss.<br />

3<br />

Final push to protect once-in-a-lifetime<br />

landscape<br />

SOUTHERN ONTARIO<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is working on a major conservation project to help protect<br />

and care for 8,000 hectares near Bancroft, Ontario.<br />

Hastings Wildlife Junction provides some of the best<br />

remaining habitat for many species at risk and wide-ranging<br />

mammals, including elk, birds and turtles. Located within<br />

the Lake Ontario watershed and headwaters for the Bay of<br />

Quinte, the project is particularly critical for maintaining the<br />

water quality for local aquatic life and communities on the<br />

coast of Lake Ontario. Vast amounts of carbon are stored in<br />

its forests and wetlands.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is the only organization of its kind working in Canada<br />

to deliver this scale of conservation impact, with a proven<br />

track record of connecting, conserving and caring for vast<br />

natural areas.<br />

To date, 5,000 hectares of the Hastings Wildlife Junction<br />

have been protected, but there is more to be done. <strong>NCC</strong>’s goal<br />

is to conserve 8,000 hectares of intact forest and wetlands here.<br />

Join us in this historic effort by making a one-time gift or multiyear<br />

pledge to ensure the future of Hastings Wildlife Junction.<br />

Learn more at natureconservancy.ca/hastings.<br />

Hastings Wildlife Junction<br />

Wild + Pine Sustainability has<br />

been working in ecosystem<br />

restoration across Canada<br />

for more than a decade.<br />

Using eco-technology to grow<br />

seedlings in their custom<br />

greenhouse, they are able to<br />

mimic the light and conditions<br />

found in the ecosystems where<br />

the seedlings will eventually<br />

be planted.<br />

In 2020, Wild + Pine<br />

approached the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>)<br />

and offered to design and<br />

implement a crowd-funded<br />

project. This project allowed<br />

Canadian businesses that<br />

balance purpose and profit by<br />

considering the impact of their<br />

work to fund the reforestation<br />

and restoration of 25 hectares<br />

of former agricultural land on<br />

an <strong>NCC</strong> property in Central<br />

Alberta. In 2021, Wild + Pine<br />

prepped the site and planted<br />

52,000 seedlings of trembling<br />

aspen, balsam poplar, paper<br />

birch, white spruce and larch,<br />

along with complementary<br />

shrub species. Another 5,000<br />

seedlings will be planted in<br />

<strong>2022</strong>, and <strong>NCC</strong> volunteers will<br />

help weed the newly planted<br />

site to give the seedlings room<br />

to thrive.<br />

Every tree planted creates even<br />

more habitat for native species<br />

in Alberta. As a partner, Wild +<br />

Pine is helping accelerate the<br />

pace of conservation.<br />

natureconservancy.ca

CLOSE<br />

ENCOUNTERS<br />

Hidden in plain sight<br />

By Doug van Hemessen, Nova Scotia stewardship manager, <strong>NCC</strong><br />

Ioften go out for an “aimless wander,” especially<br />

in the woods surrounding my home.<br />

It is an opportunity for me to leave my<br />

preoccupied mind and open my awareness<br />

to the surrounding environment. Seeing, listening,<br />

smelling, touching...even tasting, if<br />

something edible is on hand. No destination,<br />

no plan, no formal hike.<br />

It is with such a mindset that I discover<br />

details; the small, the overlooked. I’m thrilled<br />

by the tiny pockets of the “universe” that<br />

I find. Often this means lichens and mosses;<br />

things you need to stop and really look at to<br />

appreciate. Intricacies appear. It takes time<br />

to observe. To really look, to really see.<br />

Lichens are all around but often unnoticed.<br />

They can be found worldwide, from ocean<br />

coasts to mountain peaks, from the Arctic<br />

to Antarctica.<br />

They grow on almost any surface, in many<br />

diverse (and sometimes weird) forms. Rocks,<br />

soil and other plants are all homes for lichens.<br />

In areas freshly denuded of vegetation, lichens<br />

are typically the first organisms to gain a<br />

foothold. They are the foundation of more<br />

complex ecosystems.<br />

Lichens’ abilities to withstand extremes<br />

of temperature and drought also amaze me.<br />

However, many are sensitive to air pollutants.<br />

Their absence can be an indication of<br />

poor air quality.<br />

Depending on where you are, lichens<br />

may be both discrete and obvious. Some<br />

are showy, others require a magnifying<br />

glass or loupe to reveal an amazing world<br />

of details.<br />

A favourite of mine is called old man’s<br />

beard. Its shaggy, stringy strands remind<br />

me of pale greenish-grey tinsel on a Christmas<br />

tree.<br />

Sadly, despite their ubiquitous and<br />

generally hardy nature, some lichens are<br />

designated as species at risk. For example,<br />

boreal felt lichen and vole ears lichen are<br />

endangered. Their decline is linked in part<br />

to prevailing winds that bring pollution from<br />

central Canada and the eastern U.S., which<br />

falls in Nova Scotia, my home province, as<br />

acid rain. Pollution isn’t the only threat; they<br />

are also threatened by land use changes and<br />

climate change.<br />

Time spent in nature is time well spent.<br />

Get yourself out there. Pause.<br />

Close your eyes. Listen. Smell.<br />

Feel. Breathe. Let go of the thinking that<br />

preoccupies you. Open your eyes. Can you<br />

find a lichen?1<br />

TERRY ALLEN / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO.<br />

18 SPRING <strong>2022</strong> natureconservancy.ca

LET YOUR<br />

PASSION<br />

DEFINE<br />

YOUR<br />

LEGACY<br />

Your passion for Canada’s natural spaces defines your life; now it can define<br />

your legacy. With a gift in your Will to the Nature Conservancy of Canada,<br />

no matter the size, you can help protect our most vulnerable habitats and the<br />

wildlife that live there. For today, for tomorrow and for generations to come.<br />

Order your free Legacy Information Booklet today.<br />

Call Marcella at 1-877-231-3552 x 2276 or visit DefineYourLegacy.ca

YOUR<br />

IMPACT<br />

Chignecto Isthmus<br />

Moose Sex project<br />

gets a boost<br />

The conservation of a large parcel<br />

of forest, wetland and coastline,<br />

totalling close to 400 hectares on<br />

the Chignecto Isthmus, was made<br />

possible thanks to a generous gift<br />

of land, and support from the<br />

Natural Heritage Conservation<br />

Program. Dubbed the Moose Sex<br />

Corridor, the isthmus allows<br />

endangered moose in Nova Scotia<br />

to connect with moose in New<br />

Brunswick. To date, you have helped<br />

protect 1,949 hectares on both sides<br />

of the isthmus.<br />

Five generations<br />

Five generations of the Pisony family have homesteaded what is now an<br />

879-hectare property in the Castle-Crowsnest Watershed Natural Area of Alberta.<br />

This working ranch boasts forests, grasslands and vital wetlands — one of the<br />

rarest habitats in Alberta. With support from the Natural Heritage Conservation<br />

Program and working with <strong>NCC</strong>, the family placed a conservation agreement on<br />

a portion of the land, ensuring the future of the area’s wildlife and the quality of<br />

the waters that flow into Oldman River.<br />

Thank you for all you do for nature in Canada!<br />

JULY 28–AUGUST 1, <strong>2022</strong><br />

This upcoming August<br />

long weekend, grab your<br />

camera and spend some<br />

time outdoors observing<br />

nature around you.<br />

Together, we’ll document<br />

and grow the inventory<br />

of species across the<br />

country, so that science<br />

and conservation planners<br />

can use the data for<br />

future protection and<br />

conservation. Registration<br />

opens in June; keep an<br />

eye out for your invitation<br />

or subscribe for emails if<br />

you haven’t already.<br />

natureconservancy.ca/<br />

signmeup<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: MIKE DEMBECK; BRENT CALVER.