Paysages virtuels et analyse de scénarios pour évaluer les impacts ...

Paysages virtuels et analyse de scénarios pour évaluer les impacts ...

Paysages virtuels et analyse de scénarios pour évaluer les impacts ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

- crop production objectives: the allocation of crops on the field pattern of farm fulfills production<br />

objectives s<strong>et</strong> by the farmer (Thenail and Baudry, 1994), thus farm-types may be characterized by<br />

specific crop production objectives. This is particularly true for fod<strong>de</strong>r production (grass and silage<br />

maize), supposed to fulfill the need of the cattle; these production objectives will be assessed using<br />

the area <strong>de</strong>dicated to each crop, assuming that the yield potentials are homogeneous over the whole<br />

catchment;<br />

- spatial distribution of crops: to optimize the use of the farm labor time, fields implying a lot of<br />

operations (soil work, field input and crop management, shifting or milking of cattle) are located<br />

closer to the farmstead (Baudry <strong>et</strong> al. 2006). Farm-types may be characterized by specific mean<br />

distances b<strong>et</strong>ween the crop fields and the farmstead;<br />

- soil waterlogging: some crops are sensitive to soil waterlogging (Dogliotti <strong>et</strong> al., 2003; Hou<strong>et</strong> and<br />

Hubert-Moy, 2006).<br />

Topography was not inclu<strong>de</strong>d as a significant driving factor because of the observed gentle slopes. We<br />

assumed that these spatial driving factors were time-invariant over the 1993-2002 period because previous<br />

studies showed that a combination of driving factors can be steady over several <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s (Aspinall, 2004),<br />

particularly when socio-economic factors are stable over the observed period (Pocewicz <strong>et</strong> al., 2008), which<br />

was the case. Moreover, b<strong>et</strong>ween 1993 and 2002, the area exchanged b<strong>et</strong>ween farmsteads was <strong>les</strong>s than 50 ha<br />

and concerned 8 of 37 farmsteads, without significantly modifying their field pattern. The significance of the<br />

presumed spatial factors was tested by non-param<strong>et</strong>ric Wilcoxon comparison tests (p=0.95) b<strong>et</strong>ween a s<strong>et</strong> of<br />

observed annual indicators with either a targ<strong>et</strong> value or another of indicators.<br />

Crop production objectives<br />

To test the existence of a farm-type effect on crop production objectives, we compared the crop proportions<br />

of a farm-type (expressed as percentages of the area occupied by the farm-type) to the proportions observed<br />

on the whole catchment area.<br />

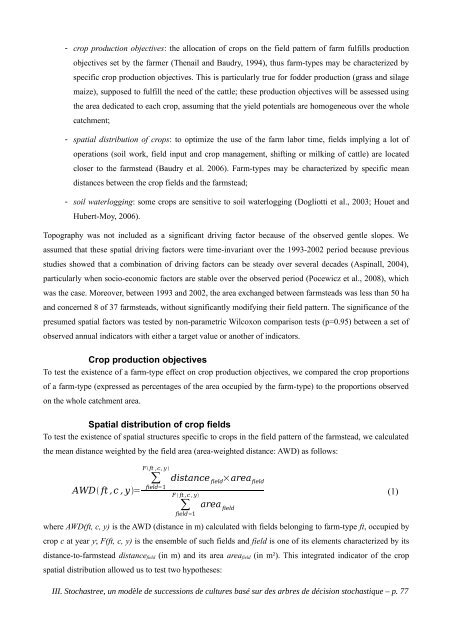

Spatial distribution of crop fields<br />

To test the existence of spatial structures specific to crops in the field pattern of the farmstead, we calculated<br />

the mean distance weighted by the field area (area-weighted distance: AWD) as follows:<br />

AWD ft ,c , y=<br />

F ft ,c, y <br />

∑<br />

field=1<br />

F ft ,c , y<br />

∑ area field<br />

field=1<br />

distance field ×area field<br />

where AWD(ft, c, y) is the AWD (distance in m) calculated with fields belonging to farm-type ft, occupied by<br />

crop c at year y; F(ft, c, y) is the ensemble of such fields and field is one of its elements characterized by its<br />

distance-to-farmstead distancefield (in m) and its area areafield (in m²). This integrated indicator of the crop<br />

spatial distribution allowed us to test two hypotheses:<br />

III. Stochastree, un modèle <strong>de</strong> successions <strong>de</strong> cultures basé sur <strong>de</strong>s arbres <strong>de</strong> décision stochastique – p. 77<br />

(1)