Part Two – post 1920s - Newcastle City Council

Part Two – post 1920s - Newcastle City Council

Part Two – post 1920s - Newcastle City Council

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

We are building a civic monument second to none outside the <strong>City</strong> of Sydney.<br />

… It will result in increasing civic pride in the minds and lives of the citizens of<br />

this great city. It will bring about a realisation of its civic importance as well as<br />

its commercial manufacturing and industrial prominence.<br />

10 Morris Light<br />

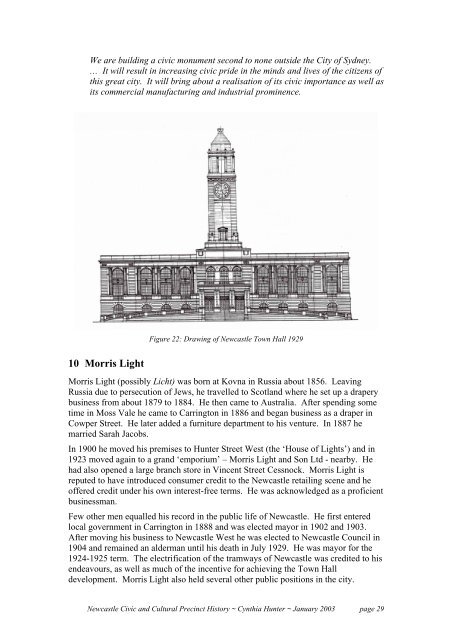

Figure 22: Drawing of <strong>Newcastle</strong> Town Hall 1929<br />

Morris Light (possibly Licht) was born at Kovna in Russia about 1856. Leaving<br />

Russia due to persecution of Jews, he travelled to Scotland where he set up a drapery<br />

business from about 1879 to 1884. He then came to Australia. After spending some<br />

time in Moss Vale he came to Carrington in 1886 and began business as a draper in<br />

Cowper Street. He later added a furniture department to his venture. In 1887 he<br />

married Sarah Jacobs.<br />

In 1900 he moved his premises to Hunter Street West (the ‘House of Lights’) and in<br />

1923 moved again to a grand ‘emporium’ <strong>–</strong> Morris Light and Son Ltd - nearby. He<br />

had also opened a large branch store in Vincent Street Cessnock. Morris Light is<br />

reputed to have introduced consumer credit to the <strong>Newcastle</strong> retailing scene and he<br />

offered credit under his own interest-free terms. He was acknowledged as a proficient<br />

businessman.<br />

Few other men equalled his record in the public life of <strong>Newcastle</strong>. He first entered<br />

local government in Carrington in 1888 and was elected mayor in 1902 and 1903.<br />

After moving his business to <strong>Newcastle</strong> West he was elected to <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong> in<br />

1904 and remained an alderman until his death in July 1929. He was mayor for the<br />

1924-1925 term. The electrification of the tramways of <strong>Newcastle</strong> was credited to his<br />

endeavours, as well as much of the incentive for achieving the Town Hall<br />

development. Morris Light also held several other public positions in the city.<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 29

In the early <strong>1920s</strong> Morris Light set out on a world tour followed by a second tour to<br />

South Africa where his sister lived. He collected much information pertaining to local<br />

government, the whole of which he placed at the disposal of the district’s councils.<br />

He was a great supported of the Town Hall project before his travels but his<br />

experience in overseas countries convinced him that for a city the size and importance<br />

of <strong>Newcastle</strong>, a Town Hall was an absolute necessity. Upon his return he set to work<br />

to develop a self-supporting model, which was eventually adopted. He is credited<br />

with ending years of indecision about a Town Hall. Shortly after his election as<br />

mayor, he brought forward the mayoral minute that initiated the works program.<br />

It was a pitiable circumstance that Morris Light’s death occurred prior to the<br />

completion of the grand civic buildings that he played so great a role in achieving.<br />

Many people at the time though that the Town Hall itself was a fitting memorial to<br />

him.<br />

Morris Light, who lived to the age of 74 years, was survived by his wife, a son and<br />

three daughters. Prior to his death he lived in Ocean Street Merewether. He was a<br />

notable member of the Jewish community. He is buried in Sandgate Cemetery.<br />

Indicative of the esteem in which the citizens of <strong>Newcastle</strong> held him, over 3000<br />

people were reported to have gathered at the gravesite on that occasion. 42<br />

After Morris Light’s death, his son carried on the successful business until his own<br />

death in 1950. The Light stores were subsequently sold to Grace Brothers.<br />

In 1993, the University of <strong>Newcastle</strong> received a bequest of about $1.5 million under<br />

the will of Reta Light, Morris Light’s youngest and last surviving daughter, ensuring<br />

that her family name continued to be linked with the attributes of generosity and civic<br />

pride ascribed to her father. 43<br />

11 Celebration<br />

Opening the Town Hall and Civic Theatre was accompanied by a week-long event<br />

called ‘Civic Week’. The Theatre attracted most interest and here opening night was<br />

a gala affair unparalleled in the history of <strong>Newcastle</strong>.<br />

12 Civic Theatre<br />

Civic Theatre was designed as a fully equipped live theatre. However its primary use<br />

was as a cinema under lease to Hoyts. Talking pictures arrived in <strong>Newcastle</strong> in 1929<br />

and the Civic Theatre showed them from opening night.<br />

Civic Theatre remained predominantly a movie house until 1973 when Hoyts<br />

terminated their lease at a time when many cinemas closed. <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>City</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

then upgraded the theatre to attract live productions of international standard, such as<br />

the Australian opening of Jesus Christ Superstar in 1975, ballet, plays, orchestral<br />

concerts and other performances. Upgrading took several years and included<br />

improved backstage facilities, new lighting and other equipment, and a new curtain.<br />

The Civic could seat about 1600 people and was the largest regional live theatre in<br />

Australia.<br />

42 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 27, 29 and 30 July, 1929<br />

43 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Herald 17 May 1993<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 30

In the 1980s it became apparent that major restoration was essential in order to attract<br />

the performances necessary for efficient operation. In 1989 <strong>Council</strong> appointed<br />

architects to draw up plans.<br />

Dame Joan Sutherland launched a public appeal for funds in July 1991. This, together<br />

with council allocation enabled stage one of major works to be commenced in 1992.<br />

Later stages of the work were assisted with government funding. The total<br />

undertaking included replacement seating in and restoration of the main auditorium,<br />

air conditioning, a new ground floor restaurant, a new performance space, new<br />

dressing rooms and facilities, and fire safety upgrade. Outside, Wheeler Place was<br />

converted into a landscaped pedestrian plaza. During the works period, the public<br />

were invited to tours of inspection of the theatre. Civic Theatre reopened in<br />

November 1993.<br />

Figure 23: Civic Theatre complex in 1929<br />

13 The Wintergarden or Exhibition Hall<br />

The 1929 building complex that comprised the Civic Theatre, shops, offices and work<br />

or sample rooms also contained ‘a fine room with ticket and other offices, retiring<br />

rooms, servery and other conveniences’ above the shops on the first floor. This<br />

Exhibition Hall Wintergarden was available for public use. When opened in 1929 a<br />

description noted that the Wintergarden combined ‘beauty, dignity and simplicity.<br />

For the most part it is in chaste white relieved by pale gold. It has a splendid jarrah<br />

parquetry floor suitable for dancing, an orchestral reserve, and a roomy servery.<br />

Overlooking Hunter Street, the Wintergarden seems an ideal ballroom’. 44<br />

In the 1960s this space may have been used for council business.<br />

In 1972 council rented the Wintergarden as an annex to the Conservatorium of Music.<br />

Although renovations were proposed they did not eventuate. <strong>Council</strong> subsequently<br />

leased the Wintergarden to the Hunter Valley Theatre Company (HVTC) in 1978 and<br />

assisted the Conservatorium to move to the Mackie’s Warehouse Building.<br />

HVTC formed in 1976 as a semi-professional theatre company. The first play was<br />

staged at the 950-seat Duncan Theatre at <strong>Newcastle</strong> University. Search for a 200-seat<br />

theatre led to council considering leasing the Mackie Warehouse to the HVTC, but the<br />

44 Construction and Local Government Journal 27 April 1927, <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 30<br />

November 1929<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 31

former Wintergarden was the better option and conversion plans followed for a Civic<br />

Playhouse.<br />

The 1992 restoration plan for the Civic Theatre included as a later stage of work the<br />

enlargement of the performance space of the Civic Playhouse with a link to the Civic<br />

Theatre facilities. However, this work was not undertaken at the time and HVTC<br />

occupancy terminated in July 1996. Civic Playhouse closed in 1998/9 because the<br />

facility no longer met fire safety and access regulations. In April 1999 and again in<br />

August 2001 investigations were made into refurbishment of the Civic Playhouse with<br />

reconfiguration of the seating. 45 A public forum had debated the status and future of<br />

the Playhouse in May 2000. 46 Options for reopening the Civic Playhouse are still<br />

under investigation.<br />

Figure 24: <strong>Part</strong> of lithograph of <strong>Newcastle</strong> in 1889. Darby Street is diagonally placed. The land<br />

section bounded by Darby, Hunter, Auckland and King Streets is represented as well built upon and for<br />

diverse uses. Larger buildings face Hunter Street. The eastern part of Civic Park is fenced but not yet<br />

industrialised. A coal train passes along Burwood Street towards Hunter Street<br />

45 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Herald 19 April 1999, 21 August 2001<br />

46 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Herald 6 May 2000<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 32

14 Civic Park - acquiring the land<br />

The table below is a summary of the stepwise process of council’s acquiring the land<br />

that makes up Civic Park. The individual parcels are indicated in the accompanying<br />

plan.<br />

1921 Lot 6 Acquired by council for a railway siding associated with<br />

electricity works in April 1921. In 1957, consolidated with<br />

Civic Park.<br />

1929 Lots 46 & 47 Resumed in November 1929 for the purpose of the erection<br />

of administrative and other buildings for the Electricity<br />

Department of the <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>City</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

Transferred to the General Fund (January 1939)<br />

1938 Lots 4 & 7 Acquired by council for ‘civic purposes’ from R<br />

Breckenridge and others October 1938<br />

1946 Lot 9 Acquired by council for ‘Civic Purposes’ from James Sandy<br />

P/L August 1946. The area required for widening Darby<br />

Street was dedicated a public road in September 1966 and<br />

the residue were dedicated as ‘Public Reserve’.<br />

1947 Lot 3 Acquired by council for consolidation and for ‘Civic<br />

Purposes’, from Union Trustee Company of Australia Ltd in<br />

June 1947<br />

1958 <strong>Part</strong> Burwood Acquired by council from AA Company in June 1958<br />

Rail Line<br />

1964 Lots 2, 5 & 8 Acquired by council from G H Varley P/L February 1964<br />

for open space and road widening<br />

1964 Lot 1 Acquired by council from <strong>Newcastle</strong> Building and<br />

Investment Company Ltd in August 1964 for open space<br />

and road widening.<br />

1979 Civic Park Civic Park dedicated as Public Reserve.<br />

1987 Civic Park Zoned 6(a) Open Space (<strong>Newcastle</strong> LEP 1987)<br />

Figure 25: The<br />

accompanying plan<br />

with allotments<br />

numbered, and this<br />

summary of<br />

acquisition, is from<br />

the Report of the<br />

Town Clerk No 24 of<br />

7 November 1978,<br />

moved to <strong>Newcastle</strong><br />

Region Public<br />

Library in April 1986<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 33

When interviewed in 1964 about the Thomas Cook’s house Lucerna, Mrs Cutts<br />

recalled that before 1900 ‘Civic Park was a swamp and horse paddock’. 47 The land<br />

was mostly vacant when the 1889 Illustration was drawn (Figure 24). The land was<br />

still mostly vacant when surveyed in 1896 (Local History Library Map, C 919.442/34-<br />

26, <strong>Newcastle</strong> and Suburbs Sheet 28, copy not included). 48<br />

Subsequently timber millers and merchants Andrew Cook and Robert Breckenridge<br />

used the low-lying land on either side of the coal railway as timberyards. Several<br />

engineering workshops, including Varley’s, were built on the Darby and King Streets<br />

frontages.<br />

In 1921 <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong> bought the first piece of this land as a railway siding for<br />

the delivery of coal to the Sydney (or Tyrrell) Street power generation plant. When<br />

the Town Hall was nearing completion, lots 46 and 47 (Figure 25) were bought for the<br />

Electric Supply Department but were used instead in association with beautification<br />

of the surrounds of the Town Hall. 49 Mr W Grant of the Sydney Botanical Gardens<br />

provided a simple and inexpensive landscape plan. This was the origin of Civic Park.<br />

Figure 26: Early<br />

beautification of<br />

Civic Park<br />

included an<br />

avenue of fig trees<br />

along the Burwood<br />

coal railway line<br />

In summary, the evolution of Civic Park began with the land owned by the AA<br />

Company prior to 1900s and the land use associated with the AA and Burwood<br />

Companies railways. Timberyards were established on either side of Burwood<br />

Railway in the early 1900s. Property resumed in <strong>1920s</strong> by <strong>Council</strong> for the Electrical<br />

Supply Department was used instead for beautification of the Town Hall surrounds<br />

and provided the park nucleus. The railway corridor was resumed in the 1950s.<br />

Properties along Darby Street were resumed in the 1960s. A number of landscape<br />

plans followed and the James Cook Memorial Fountain opened in 1970.<br />

15 Christie Park<br />

The land immediately west of Town Hall was vacant in 1929. In the 1930s council<br />

purchased additional land here extending to the Auckland Street corner for offices for<br />

47 Interview with E M Cutts, descendant of Henry Dangar, about ‘Lucerna’, <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning<br />

Herald 28 November 1964 p. 8<br />

48 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Local Studies Library map C 919.442/34-26<br />

49 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 12 December 1929<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 34

the Electric Supply Department. Christie Park was subsequently created in the<br />

intervening space, allowing for an access road around the Town Hall and Civic<br />

Theatre.<br />

Figure 27: photo shows<br />

paths and palm planting<br />

in the space between the<br />

Town Hall and Nesca<br />

building, also planting in<br />

Civic Park<br />

At the time of preparation of the Civic Park Plan of Management 1989, Christie Place<br />

was described as owned by <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong> and zoned 5(a) Special Uses (Public<br />

Buildings). This provision allowed for possible development or access associated<br />

with Nesca House and other council owned property extending through to Hunter<br />

Street.<br />

The Shortland Memorial, erected as a fountain near <strong>Newcastle</strong> Beach in 1897 and<br />

subsequently removed to Reid Park in 1938 to allow beach improvements, was<br />

removed again to Christie Park in 1978. The ‘fountain’ use was not restored in 1938,<br />

or in 1978.<br />

Christie Street, a private road owned by council, provides a thoroughfare from King<br />

Street to Wheeler Place. This lane is used to provide rear stage access to the theatre<br />

for large delivery vehicles, and to the Civic Arcade building.<br />

Christie Park is used as a pedestrian thoroughfare, a rest area and is often visited at<br />

lunchtime by city office workers. The park enhances the setting of the surrounding<br />

cultural and civic buildings.<br />

16 The Electric Supply Department and Nesca House, 1939<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Municipal <strong>Council</strong> began generating electricity in 1890. Their generating<br />

plant was east of Darby Street between Tyrrell and Queen Streets. Administration<br />

was by the council’s ‘Electricity Supply Department’ or ESD. The ESD expanded<br />

and by the early 20 th century, provided electricity to many suburban council areas as<br />

well as <strong>Newcastle</strong>. In the early <strong>1920s</strong> the council bought the first land in Civic Park<br />

(lot 6 Figure 25) for a rail siding for the delivery of coal to the generating plant.<br />

Cook’s timber yard (lot 47) was purchased several years later for ESD and other<br />

purposes of which park use was actually chosen. Apparently in the late <strong>1920s</strong> an<br />

electric appliances showroom was built on the corner of Hunter Street and Wheeler<br />

Place. Administration of the ESD moved into the Town Hall after 1929 until Nesca<br />

House was built in 1939.<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 35

Figure 28: image of the<br />

ESD showroom adjoining<br />

the Bennett and Wood<br />

building in Hunter Street<br />

In the mid-1930s, <strong>Council</strong> acquired land on the Auckland Street corner and decided to<br />

build new headquarters for the ESD here. A blacksmith and wheelwright formerly<br />

occupied a large shed on the corner site. The site adjoined the former Salvation Army<br />

barracks and an Oddfellows Hall.<br />

Sydney architect Emil Sodersteen designed and supervised the modern building in<br />

association with <strong>Newcastle</strong> architects Pitt and Merewether. The building was<br />

completed in 1939 and became known as the <strong>Newcastle</strong> Electricity Supply <strong>Council</strong><br />

Administration or Nesca.<br />

Figure 29: Nesca<br />

House. This image is<br />

probably earlier than<br />

Figure 27, as indicated<br />

by the landscaping of<br />

Christie Park<br />

The Electricity Commission (State government) took over council’s role in 1957 and<br />

the Shortland County <strong>Council</strong> (SCC), a regional organisation, replaced the ESD. The<br />

Nesca building (which passed to the SCC) was enlarged in 1959 and 1970 and<br />

extensively renovated in 1983 and 1984.<br />

In the 1970s plans were made to move the undertaking, then known as ‘Shortland<br />

Electricity’, to Wallsend. This move occurred in stages and was completed by 1990.<br />

A new corporate structure was called ‘Orion Energy’ and following amalgamation<br />

with other suppliers, ‘Energy Australia’.<br />

Nesca House was available for other uses from the late 1980s and in 1991 <strong>Newcastle</strong><br />

<strong>City</strong> <strong>Council</strong> considered buying back the building for more office space but did not<br />

proceed with the purchase. The vacated Nesca House was used as professional<br />

offices, and part occupied by the Conservatorium of Music. The University of<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> bought the building in 1992 for use by the Faculty of Law and the<br />

Conservatorium of Music.<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 36

17 Civic precinct development in the 1930s<br />

In the late 1930s when Nesca House was built, other new developments were<br />

occurring in the civic precinct. These included Morpeth House (1936), the Australian<br />

Provincial Association Ltd building west of the civic shops (1937), the new<br />

Clarendon Hotel (1940), and another unusual wedge shaped building to replace the<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Permanent Building, Investment, Land and Loan Society headquarters.<br />

Figure 30: The 1937<br />

Australian Provincial<br />

Association Building,<br />

west of the civic shops,<br />

now Civic Arcade<br />

Contractor C Johnson erected Morpeth House, a three-storey commercial building in<br />

the Art Deco style in 1936 for Mr A Saroff of Cessnock and West Maitland. There<br />

were two entrances to Hunter Street and the building appears to have been used for<br />

retail purposes. Up-to-date facilities in the building included an electric lift, plate<br />

glass windows and excellent natural lighting and ventilation.<br />

The National Trust in 1990 described the row of buildings between Burwood Street<br />

and the Bennett building as representative of:<br />

… many aspects of <strong>Newcastle</strong>’s development during the second half of the 19 th<br />

century and the first half of the 20 th century. Commercial, retail and residential<br />

interests are represented, illustrating changing social forces, building uses and<br />

architectural progress. The group is very varied in appearance yet retains a<br />

harmony of scale and a great townscape attractiveness. 50<br />

Figure 31: Hunter<br />

Street streetscape<br />

between Wheeler Place<br />

and Burwood Street. To<br />

the right of the Fred c<br />

Ash building is the<br />

Bennett and Wood<br />

building, and to the left<br />

is the 1940s Clarendon<br />

Hotel. Photo taken on<br />

day of demolition of<br />

buildings east of the<br />

Clarendon. The 1970s<br />

bank, right, has also<br />

been demolished, for an<br />

enlarged Wheeler Place<br />

50 Quoted in ‘<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic Site Heritage Impact Statement’ by Godden Mackay 1996, p. 71<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 37

18 1940s plans for a civic square and cultural centre<br />

In 1938, after many years of negotiation, several district municipalities were joined<br />

together to form the Greater <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong>. To commemorate the event, the<br />

mayor and all new aldermen resolved that the ‘Town Hall shall be known in future as<br />

the <strong>City</strong> Hall’. 51<br />

Proposals for a cultural centre for <strong>Newcastle</strong> in the vicinity of the Town Hall and<br />

Civic Theatre progressed in the late 1930s and revived after the war. The<br />

accompanying plan for a civic centre was prepared in 1945 by the city architect Mr<br />

Parkinson. It was a long-range view of possible development and was presented for<br />

discussion to a public meeting. In this plan, Wheeler Place has been extended to<br />

make Civic Park a true square with a war memorial as centrepiece.<br />

Several sites for a cultural centre were under consideration at the time. Parkinson’s<br />

scheme suggests the site between Wheeler Place extended and Darby Street and future<br />

public buildings to house a variety of government offices were suggested along<br />

Laman Street.<br />

The council preferred the elevated Laman Street site for the cultural centre.<br />

Government buildings, or any other large buildings west of Darby Street were<br />

rejected in favour of preserving extensive views to and from the cultural centre.<br />

Figure 32: Parkinson’s<br />

1945 plan as reproduced<br />

in the <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning<br />

Herald 20 October 1945<br />

By 1947 the Northumberland County <strong>Council</strong>, set up by the State government to<br />

provide planning expertise for <strong>post</strong>-war renewal, made public its plans for the future<br />

development of <strong>Newcastle</strong>. One of the county council plans for the civic area is<br />

shown below (Figure 33). In this plan elimination of the Burwood coal railway has<br />

allowed resumption of part of Dawson Street. Auckland Street has been extended<br />

south. The Baptist Tabernacle is moved to another site in Auckland Street. King and<br />

Darby Streets are widened as tree-lined ‘boulevards’. The land bounded by Burwood,<br />

Darby and King Street is a green wedge that links and opens up the civic centre area<br />

to the harbour and allows replanning of the road traffic system. A large roundabout<br />

was proposed for the space taken today by the Taxation Offices. Civic Park occupies<br />

the whole land section except for St Andrew’s Church, forming a fine civic square. A<br />

51 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 25 March 1938<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 38

walkway and flight of stairs links the Town Hall with the cultural centre sited in<br />

Laman Street.<br />

The Northumberland County <strong>Council</strong> scheme also promoted an alternative site for the<br />

cultural centre <strong>–</strong> one facing King Street near Union Street. This potential site was to<br />

be enhanced by resuming a ‘square’ extending between King and Hunter Streets that<br />

opened views to the harbour. The proposal showed a way to break up <strong>Newcastle</strong>’s<br />

long parallel street pattern.<br />

Greater <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong> was not in favour of the Northumberland County<br />

<strong>Council</strong>’s plans for the extension of Auckland Street, the green wedge and the traffic<br />

roundabout and rejected the cultural centre site in King Street.<br />

The Northumberland County <strong>Council</strong> built offices on the north west corner of King<br />

and Auckland Street. The county council ceased its work in 1964 and was succeeded<br />

by the State Department of Environment and Planning. This building (or part thereof)<br />

is now owned by <strong>Newcastle</strong> University and used by the Conservatorium of Music<br />

(Figure 34).<br />

Figure 34: former offices and crest of the Northumberland County <strong>Council</strong><br />

Figure 33:<br />

Northumberland County<br />

<strong>Council</strong> Plan as<br />

published in <strong>Newcastle</strong><br />

Sun 20 May 1949<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 39

19 Land acquisition in the 1950s and 1960s<br />

In these years <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong> acquired a number of allotments including the<br />

improved and vacant land that allowed the extension of Civic Park to Darby Street.<br />

Other negotiations brought boundary adjustments at the rear of the Presbyterian<br />

Church that would ‘tidy up the south west corner’ of Civic Park. Properties bounded<br />

by Laman, Dawson, Queen and Darby Streets were acquired, also the extensive land<br />

of the Fred c Ash company. The former Australian Provincial Association Ltd<br />

building containing the Civic Arcade was then owned by council, the year of<br />

acquisition is not presently known. The Burwood coal railway was nearing the end of<br />

its operative life and trucks ceased running in 1954. Creation of an enhanced Civic<br />

Park linking to an envisaged cultural centre was central to the acquisition of these<br />

land sections.<br />

Figure 35: Proposed landscape plan for Civic Park in 1957, as reproduced in the <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning<br />

Herald 22 October 1957<br />

20 A cultural centre for <strong>Newcastle</strong> 1949-1957<br />

In June 1949 a foundation stone was placed for the cultural centre on the council’s<br />

preferred site. This was 6 years before any work started on the building. Building<br />

commenced in the mid-1950s and the State Governor Lt Gen Sir Eric Woodward<br />

opened the War Memorial Cultural Centre on 26 October 1957.<br />

The building consisted of three floors and a basement. A <strong>Newcastle</strong> Library<br />

comprised of a central reference, lending and children’s library occupied the<br />

basement, the ground level and first or mezzanine level. The Art Gallery occupied<br />

most of the space on the second floor and the Conservatorium of Music occupied the<br />

third floor, apparently under 21-year leases.<br />

As each of these cultural activities today occupies independent premises surrounding<br />

Civic Park, creating an expanding cultural precinct, their history, establishment and<br />

growth within the <strong>Newcastle</strong> community and their relationship to the War Memorial<br />

Cultural Centre or cultural precinct will be considered separately.<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 40

Figure 36: 1960s aerial view of the civic precinct<br />

20.1 Conservatorium of Music<br />

Does any community exist without music and dance? Indigenous Australians have a<br />

heritage of corroborees and unique musical instruments. Musical societies, choirs and<br />

bands feature prominently in <strong>Newcastle</strong>’s 19 th and 20 th century history. Eisteddfods<br />

are the legacy of the district’s Welsh heritage and are ongoing. Convent schools have<br />

a tradition of excellence in music teaching. Dance Halls needed orchestras. <strong>Council</strong>s<br />

sponsored brass bands in exchange for public recitals in parks where special rotundas<br />

were built for their accommodation. Silent films needed a musical accompaniment.<br />

The proficients that taught music in the <strong>Newcastle</strong> district also encouraged<br />

performances and promoted a vision for a Conservatorium of Music.<br />

A State Conservatorium was established in 1916, which must have encouraged<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> musicians in a similar pursuit. However, social and economic adversity<br />

such as World War One and its aftermath, followed by the Great Depression of the<br />

late <strong>1920s</strong> and early 1930s were not conducive to making any advances in this quest.<br />

As is indicated elsewhere, an attempt was made to establish a cultural centre in<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> in 1936 but the country’s commitment to World War <strong>Two</strong> interrupted the<br />

emerging possibilities.<br />

When hostilities concluded in 1945 there was a countrywide desire for social<br />

betterment. Following a well-represented meeting held in the Town Hall in July 1945<br />

a committee of capable townspeople undertook the task of fundraising and planning<br />

for a building that would be a soldiers’ memorial and a home for the arts in<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong>.<br />

The plan that emerged at this time was for a building that would incorporate space for<br />

a public library, an art gallery, a conservatorium and a concert hall. A library was<br />

then conducted in a room in the Town Hall but the other three facilities were<br />

practically non-existent in <strong>Newcastle</strong>. Apparently the only available performing<br />

spaces were the main Town Hall and a smaller hall in the east of the city known as<br />

Blackall House. The Civic Theatre was strictly a film house and if a large group like<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 41

the Sydney Symphony Orchestra visited <strong>Newcastle</strong> it was usually necessary for them<br />

to use the Century Theatre at Broadmeadow.<br />

Plans, ideas and debate in the 1940s and1950s about civic precinct land involved the<br />

Greater <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong>, the Northumberland County <strong>Council</strong> and the community.<br />

The various proposals have already been mentioned. The council began to resume its<br />

preferred site, which was the land section bounded by Laman, Dawson, Queen and<br />

Darby Streets. Opposition came from those who lived in the cottages thereon and<br />

other residents and aldermen who supported them and those who opposed the cultural<br />

centre project in general. Housing was in short supply in the <strong>post</strong>-war years and the<br />

social and economic distress argument could not be ignored. Displaced residents<br />

were subsequently relocated in alternate housing.<br />

In 1946 a salaried financial organiser and assistant were appointed to seek funding for<br />

the cultural centre. At the time donations were not ‘tax deductible’. Amending this<br />

law took until early 1947. The Minister for Education the Hon J R Heffron MLA was<br />

then invited to open the fund raising appeal. His acceptance indicated that the<br />

government viewed the cultural centre favourably. This was subsequently confirmed<br />

when the State Conservatorium of Music was placed under the administration of the<br />

Department of Education.<br />

As soon as funds began to accumulate, with large sums contributed by industry,<br />

commerce, groups and individuals, the government responded with promised<br />

subsidies. Achieving the cultural centre was now assured, as was the setting up<br />

therein of a branch of the State Conservatorium.<br />

In order to help meet the demand for music tuition a temporary conservatorium was<br />

set up in 1951 in a timber barrack-type building in King Street at the eastern end of<br />

Civic Park. (In 1951 about 60 students from <strong>Newcastle</strong> were travelling to Sydney for<br />

music lessons.) Teaching commenced here in early 1952. 165 students enrolled in<br />

the first week. By the end of the first year, 388 students had enrolled and in the<br />

subsequent years of 1953 and 1954, 562 and 608 students enrolled. Conditions in the<br />

temporary building became congested. The sound of music making overflowed into<br />

Civic Park attracting the attention of passers-by. The success of the temporary<br />

conservatorium justified the establishment of a permanent music school in <strong>Newcastle</strong><br />

and the continued effort of its supporters. The principal of the conservatorium<br />

initiated a scheme to raise funds for scholarships.<br />

The temporary conservatorium can be seen in the 1960s aerial view of the civic<br />

precinct, Figure 36.<br />

The Cultural Centre Committee continued their work. Apparently there were times<br />

when ‘local politics’ was near to excluding the conservatorium from the plan. Many<br />

negotiations ensued to keep it in, and after the official opening the music school<br />

moved into the third floor. The new building provided improved facilities, 13 large<br />

studios, a large lecture room and small hall capable of seating 40 and 90 respectively,<br />

a library and administrative offices, but no auditorium.<br />

The conservatorium made remarkable growth and established important links with<br />

education, teacher training and the New South Wales University of Technology - the<br />

forerunner of the University of <strong>Newcastle</strong>, laying the foundation for <strong>Newcastle</strong>’s<br />

standing today as a significant centre of tertiary education in New South Wales.<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 42

After 1957, the Cultural Centre Women’s Fund Raising Committee continued as the<br />

‘Art Gallery and Conservatorium Committee’, raising further funds for the purchase<br />

of instruments, equipment and library items. This committee continued until 1974.<br />

By 1961 accommodation on the 3 rd floor was inadequate. In 1965 the need for a<br />

separate building was obvious. The general feeling however was that the<br />

conservatorium should remain part of the cultural centre, which could be enlarged.<br />

This proposal did not materialise and finding extra space became a matter of urgency.<br />

In 1970 an annex opened in Maitland and in 1972, the Civic Wintergarden was rented<br />

from <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong> for music tuition purposes. Proposed renovations here did<br />

not eventuate.<br />

In the mid-1970s the Art Gallery moved to a separate building and the Library took<br />

all the space vacated by the gallery. Without some of this extra space, the<br />

Conservatorium again had to look elsewhere. ‘Elsewhere’ included possible<br />

extensions to the cultural centre, a new building on the Shortland (University and<br />

Teachers College) campus, the old Teachers College site at Cooks Hill, the Town Hall<br />

(briefly a possibility after the new administration building was occupied),<br />

‘Woodlands’ in Church Street, the Century Theatre at Broadmeadow, a floor above<br />

the <strong>Newcastle</strong> Masonic Club, <strong>Newcastle</strong> East Public School, Cooks Hill High School,<br />

Fort Scratchley, and the Frederick Ash building near the new administration block.<br />

All lapsed due to financial constraints.<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong> subsequently leased the Wintergarden to the Hunter Valley<br />

Theatre Company and assisted the conservatorium to move to Mackie’s warehouse.<br />

Renovated by the Public Works Department, this space gave the conservatorium an<br />

adequate venue for concerts for the first time but otherwise was only a partial solution<br />

to the escalating need for more studio and practice space.<br />

Fortuitously in 1978 the old Salvation Army Men’s Hostel, was ‘for sale’. This was a<br />

large 5-storey building with over 50 rooms that could be used as teaching studios.<br />

The building was sound and conversion for conservatorium use was practical. The<br />

site was central and near to public transport, had parking for 50 vehicles and enough<br />

land to build the long anticipated concert hall. The government did buy the property<br />

and the Public Works Department undertook to convert the old hostel to<br />

conservatorium needs. The building was occupied in 1981.<br />

Building the concert hall on the Laman/Auckland Streets corner continuous with the<br />

former Men’s Hostel was a 1988 Bicentenary project undertaken by the Department<br />

of Public Works. The architect was John Carr in association with Suters Architects<br />

and Planners and the building contractor was R T Parker Pty Ltd. The hall can seat<br />

about 500 people. 52<br />

In 1990 the conservatorium became part of the University of <strong>Newcastle</strong>. Also at that<br />

time part of the recently- vacated Nesca House was leased for conservatorium use.<br />

In 1992 <strong>Newcastle</strong> University bought Nesca House from Shortland Electricity<br />

together with a block of land in Laman Street. 53 This was generally felt to be a<br />

welcome move that would inject new life into the city centre and provide a ‘shop<br />

front’ for the University in the inner city. The faculties to occupy space in the<br />

52 Readers are referred to Kenneth Wiseman’s book From Park to Palace for a comprehensive account<br />

of the <strong>Newcastle</strong> Conservatorium of Music 1952-1986 from which this summary is mostly derived.<br />

53 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Herald 9 December 1992<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 43

uilding were the Conservatorium of Music and the Faculty of Law. ‘University<br />

House’ is today an appropriate name for the building.<br />

The block of land in Laman Street was next to the Conservatorium of Music building<br />

and ideal for future expansion of that institution as well as car parking for students in<br />

the short term.<br />

In 1997 the conservatorium occupied ‘Northumberland House’ on the north west<br />

corner of King and Auckland Streets, the former headquarters of the Northumberland<br />

County <strong>Council</strong> and Department of Environment and Planning.<br />

In 2002, over 2,000 students were enrolled and over 150 concerts performed each<br />

year. The conservatorium is closely associated with many drama and musical groups<br />

both locally and afar and plays an important role in education and enrichment of<br />

cultural life in <strong>Newcastle</strong> and the Hunter Region.<br />

20.2 Art Gallery<br />

Proposals for <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong> to establish a <strong>Newcastle</strong> Art Gallery can be traced<br />

back to the <strong>1920s</strong> when the director of the National Art Gallery suggested that a<br />

special space be provided in the proposed new Town Hall scheme for that purpose.<br />

Then, the director assured the council, art works would be made available for<br />

exhibition from the national collection and from the Sydney Art Gallery. Apparently<br />

the National Gallery had already loaned paintings for exhibition in the Technological<br />

Museum in Hunter Street. 54 Here the Technical College conducted an Art School.<br />

The town clerk foreshadowed that a sum of money could be voted to purchase art<br />

works and also for annual prizes in order to encourage local talent and built up a city<br />

collection. The council agreed. ‘It takes something more than business and industry<br />

to make a city really great’ said the <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald editor on the<br />

following day. 55<br />

Apparently no action eventuated from this proposal for about ten years until the<br />

movement for a cultural centre for <strong>Newcastle</strong> became topical. The Town Hall had<br />

made articulate the civic aspirations of the people it was said. Now their cultural<br />

aspirations needed similar expression. A ‘Cultural Centre Advisory Committee’<br />

joined forces with the ‘Free Library Movement’, (which was part of the agenda of the<br />

‘Greater <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong>’) to forward this initiative.<br />

There was no money for this purpose. Funding for any cultural centre depended on<br />

selling for redevelopment the <strong>Newcastle</strong> School of Arts building, whose function was<br />

now ‘out of fashion’. If this were done, additional funds might be obtained from the<br />

government and the Department of Education. 56<br />

The Trustees of the School of Arts were not favourable to the idea. Their own library<br />

was available to members and the Technical College had a good reference library,<br />

they said. Advocates of the Free Library Movement (that is a library for all citizens<br />

paid for out of municipal rates) wanted a diverse collection of books that were a<br />

practical balance between fiction and reference books. The Free Library was an<br />

essential community facility, not necessarily because the people wanted access to<br />

54 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 1 November 1921<br />

55 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 2 November 1921<br />

56 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 2 June 1938<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 44

ooks but because they should have them and the council should show leadership by<br />

providing them.<br />

The council was presented with two options. The Cultural Centre Advisory<br />

Committee’s option was to establish a cultural centre to provide modern library<br />

facilities and opportunities for other cultural expression. The former would be a<br />

‘good central library with a well-serviced reference section, a children’s library, a<br />

lending library, a reading room well stocked with newspapers and periodicals and a<br />

stack room that would serve as the centre for a regional library service’. ‘Other<br />

cultural expression’ was an art gallery with hall suitable for lectures, amateur<br />

theatricals, musical recitals and accommodation for meetings of cultural and scientific<br />

societies.<br />

The second option, from the School of Arts Trustees, was to lease the upper level of<br />

their building for a library and other cultural activities. This proposal was<br />

economical, limited, temporary and makeshift and met with little enthusiasm.<br />

Apparently in 1938 two collections of paintings were on loan to the city. One <strong>–</strong> a fine<br />

collection of bird studies by Neville Cayley <strong>–</strong> ‘hangs in obscure neglect on the walls<br />

of the Longworth Institute’. The other was ‘distributed round the passageways of the<br />

Town Hall’. <strong>Newcastle</strong> urgently needed an appropriate hall to exhibit these works<br />

and others that were available. 57<br />

The committee stressed that their plan allowed for cultural activities to be closely<br />

associated with the civic centre already growing up around the Town Hall.<br />

Apparently no decision was made although agitation for a cultural centre, especially<br />

the library component, continued. <strong>Two</strong> years later ‘<strong>Newcastle</strong> Art Society’,<br />

apprehensive of being left out of the plan, promoted a central exhibition space in the<br />

city for pictures. The society wanted to improve art appreciation in the community by<br />

making good works accessible. The society asked the Minister for Education to make<br />

available the museum room at the old Technical College in Hunter Street for an art<br />

gallery. 58 Other unused halls were suggested but nothing appears to have been<br />

achieved.<br />

Some writers claim that World War <strong>Two</strong> intervened and prevented the cultural centre<br />

and art gallery from materialising.<br />

A <strong>Newcastle</strong> Art Gallery took a step closer to realisation when Dr Roland Pope<br />

(1864-1952) offered the city his collection of 3,000 books and many paintings and<br />

drawings. The offer came not from any personal association with the city but because<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> was the most populous of provincial cities then lacking the advantages of<br />

cultural institutions. The gift was conditional on providing a suitable building - a<br />

public library and gallery <strong>–</strong> to house them. Further awareness of Dr Roland Pope, his<br />

collection policies and his vision is desirable for anyone seeking to know the story of<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong>’s cultural centre.<br />

After War’s end the cultural centre movement was rekindled. A public meeting in<br />

1945 led to the formation of a committee to advance the cause. Choosing a site<br />

involved the community in many debates. Despite opposition by many people<br />

(including local residents and later, the planner of the Northumberland County<br />

<strong>Council</strong>) the <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong> decided upon the Laman Street site in August 1946.<br />

57 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 31 October 1938<br />

58 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 19 April 1940<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 45

A foundation stone laying ceremony here by the State governor was arranged for June<br />

1949. This was 6 years before any work started on the building. The inscription on<br />

the stone had to be changed when it was incorporated into the building in 1955. 59<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong> resumed the Laman Street site with the exception of the Baptist<br />

Tabernacle. A group of <strong>Newcastle</strong> architects formed a panel named NEWMEC and<br />

by cooperative effort were responsible for the design of the new building. This panel<br />

consisted of architects Castleden and Sara, Hoskins and Pilgrim, Lees and Valentine<br />

and Pitt and Merewether. 60 Contractor V F Doran and Sons Ltd of <strong>Newcastle</strong> won the<br />

building tender. The building was smaller than the one proposed in the late 1930s.<br />

How this substantial building was paid for should not be forgotten. Major donations<br />

included an unknown amount from the council, and £10,000 from the Joint Coal<br />

Board, £10,000 from BHP, £2,500 from Lysaghts, £2,000 from Stewarts and Lloyds,<br />

£1,500 from the <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald and amounts of £1,000 from<br />

Commonwealth Steel, Australian Comforts Fund, breweries, Scott’s Ltd and Winn<br />

and Co. The State government gave £30,000 especially for the conservatorium.<br />

About £6,000 was raised from a scheme whereby 4,500 workers in industry and<br />

offices made a regular contribution from each week’s pay for a number of years. A<br />

similar scheme was introduced in the schools whereby children gave 3d each week<br />

until they had given 10 shillings. 61<br />

The governor opened the centre in October 1957.<br />

The building was <strong>Newcastle</strong>’s official World War <strong>Two</strong> Memorial to remember and<br />

honour the service and sacrifice of so many citizens in that conflict. This was<br />

expressed in the sculptured figures placed in the memorial foyer and the inscription<br />

‘In minds ennobled here the noble dead shall live’.<br />

The building housed the library, art gallery and conservatorium, provided a home for<br />

the Roland Pope collection and was a significant move in the council’s plan to<br />

provide <strong>Newcastle</strong> with a worthy civic and cultural precinct.<br />

Before the cathedral-like avenue of trees in Laman Street began to overshadow it, the<br />

cultural centre on the crest of the hill south of Civic Park was prominent and imposing<br />

with modern lines that complemented the ornate Corinthian façade of the adjoining<br />

Baptist Tabernacle and the Gothic design of St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church.<br />

The art gallery was at first housed in half of the second floor of the cultural centre<br />

until 1962 when the entire floor was made available for the growing collection. In<br />

1963 the von Bertouch Gallery - the first commercial gallery to be established outside<br />

an Australian capital city - opened in Laman Street. 62 This was a significant marker<br />

of growing public interest in art for which the Art Gallery can claim influence.<br />

Commercial firms, too, were taking an interest in art through sponsorship.<br />

In 1964 and again in 1966 crises arose when the abstract art that the director<br />

purchased and the buying of Fred William’s ‘Landscape in Upwey’ for $1,700<br />

outraged some aldermen. 63 . The outcome was that no restrictions were to be imposed<br />

59 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 13 May 1949, 22 October 1957<br />

60 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 22 October 1957<br />

61 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 22 October 1957<br />

62 ‘A Life Devoted to Art’, <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 22 February 1983<br />

63 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 7 March 1964, 3 and 7 November 1966<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 46

on purchases by the director. Visitor numbers to the gallery kept increasing,<br />

indicative of public interest and support.<br />

By the mid-1960s the library, conservatorium and art gallery were outgrowing their<br />

available space and examining their future needs. 64 Much negotiation ensued. In the<br />

early 1970s the vacant Frederick Ash buildings then owned by the council were<br />

proposed for new gallery space. The government architect made a detailed<br />

investigation, drew up designs and estimated costs. 65 The ‘feasible’ proposal was<br />

made public in 1971. <strong>Two</strong> years later the State government granted $100,000 towards<br />

the conversion ‘on the recommendation of the Minister for Cultural Activities’. 66<br />

Similar Federal government assistance was foreshadowed. However, the Sydney<br />

Opera House was absorbing all money for cultural capital works and all the output of<br />

the government architects. Almost no funds or architectural services were available<br />

for provincial cultural projects for several years. 67<br />

Early in 1974 ‘expert advice’ and rising costs influenced the council to abandon the<br />

Frederick Ash conversion after almost four years of effort. A new building was<br />

proposed instead. 68 By choosing a site for it adjoining the cultural centre, the 1940s<br />

plan to concentrate public cultural activities in the block bounded by Laman, Queen<br />

and Darby Streets was revived. The corner site chosen has an interesting history that<br />

has already been summarised.<br />

Architect B Pile drew up plans in 1974 and construction began in October 1976. The<br />

successful tenderer was A W Gardiner Pty Ltd. Queen Elizabeth II opened the<br />

‘<strong>Newcastle</strong> Regional Art Gallery’ in March 1977. 69<br />

(Escalating costs are of interest. In 1971 the conversion of Fred c Ash buildings for the<br />

Art Gallery was estimated at $100,000. By 1973 the estimate was $335,000. Later<br />

that year $500,000 was indicated. It was then estimated that a new building would<br />

cost ‘about the same’. In 1974 an estimate of $630,000 for the new building was<br />

revised to $758,000. The cost in 1977 was $1.34 million. 70 )<br />

The <strong>Newcastle</strong> Region Art Gallery was shut for a year after the parapet of the<br />

neighbouring cultural centre fell through the gallery roof at the time of the <strong>Newcastle</strong><br />

Earthquake. The building was sealed and art works removed while extensive repairs<br />

were undertaken.<br />

20.3 The Library<br />

Historically libraries bring to mind the Mechanics Institute/School of Arts movement<br />

of the early 19 th century. This movement led to the formation of many private<br />

societies, which came to be supported by the government and were later brought<br />

under the administration of the Department of Education, but the movement that<br />

created the institutions entered a period of decline in the 20 th century.<br />

64 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald Leader, 14 October 1968<br />

65 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 26 March 1971<br />

66 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 8 August 1973<br />

67 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 21 May 1973<br />

68 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 15, 16 and 19 February 1974<br />

69 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Herald 6 June 1974, <strong>Newcastle</strong> Sun 7 March 1977<br />

70 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald, 25 March 1971, 2 March 1973, 28 February 1974, 20 September 1974,<br />

7 March 1977<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 47

A 1933 survey of Australia libraries led to the 1935 Munn-Pitt Report that<br />

recommended the establishment of a system of free public libraries provided by local<br />

councils out of rate revenue supported by the State government and staffed by trained<br />

librarians. This led to the formation of the Free Library Movement to advance the<br />

recommendations and then the passing of the Library Act of 1939, which enabled<br />

councils to set up such libraries. 71 As noted, <strong>Newcastle</strong> members of the Free Library<br />

Movement were active in working towards a cultural centre for <strong>Newcastle</strong>.<br />

When the cultural centre opened another benefactor handed over his valuable personal<br />

collection to the library. Wilfred Goold, a <strong>Newcastle</strong> businessman, had devoted the<br />

leisure hours of 30 years of his life to the study and recording of <strong>Newcastle</strong>’s early<br />

history. He was a founder of the <strong>Newcastle</strong> Historical Society and at the time<br />

‘<strong>Newcastle</strong>’s foremost historian’. In 1953, when he was made a fellow of the Royal<br />

Australian Historical Society, he was the only person outside the Sydney area to<br />

receive the honour. His collection included maps, photos, books, documents and a<br />

number of artefacts. A priceless item, and one that merits the utmost veneration, was<br />

the original commission signed by Governor King for the foundation of the settlement<br />

at <strong>Newcastle</strong>. 72<br />

By 1966 the lending section of the library had been shifted to the old School of Arts<br />

building in Hunter Street. The vacated space was immediately taken for the local<br />

history collection. The reference library was also short of space. The idea was put<br />

forward that the city library should occupy the entire building (with the local history<br />

section having an entire floor) and the conservatorium and art gallery should be<br />

housed in independent facilities. 73<br />

20.4 Performing Arts<br />

21 Ceremony and Celebration<br />

Figure 37: The Goold Building<br />

A recent facility provided by <strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>City</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

as a studio for rehearsals for the local performing arts<br />

industry is the hall in Auckland Street adjoining the<br />

former Nesca House. This building was at first a<br />

meeting hall for the Oddfellows Association, and in<br />

the mid-20 th century, the furniture showrooms of the<br />

Goold family business. Performing Arts <strong>Newcastle</strong><br />

hold workshops, forums and other activities here that<br />

promote artistic talents within the <strong>Newcastle</strong><br />

community.<br />

The balcony of <strong>City</strong> Hall is traditionally used to introduce distinguished visitors to the<br />

community and Civic Park is a special place for the community to gather on these<br />

71 The Australian Encyclopaedia Volume 4 The Grolier Society of Australia 1977 p. 6, 7<br />

72 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 22 October 1957<br />

73 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald, Leader, 14 October 1968<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 48

occasions. Just two years after the cultural centre opened Princess Alexandra visited<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> and was welcomed in this manner.<br />

Figure 38: Community<br />

welcome extended to<br />

Princess Alexandra in Civic<br />

Park in 1959<br />

Opening the cultural centre and improving the Civic Park land was accompanied by<br />

the establishment of Mattara, an annual spring festival promoting <strong>Newcastle</strong>’s<br />

cultural and commercial life. In the first year 1961 an 18-day carnival of frolic,<br />

pageantry and demonstration was planned, which would extend a hand of friendship<br />

or Mattara (in Aboriginal dialect) to visitors and showcase the city to a wide<br />

audience. The headquarters of Mattara was Civic Park, ‘hub of the city’s future<br />

Civic Square now in course of development’. On opening night a parade from<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Beach to Civic Park preceded the launching ceremony and an outdoor<br />

concert. The event involved all forms of cultural expression. Performances and an art<br />

exhibition were focused in Civic Park. The winning design for a Civic Park fountain<br />

was announced.<br />

40,000 people lined the route of the procession that year, which involved 1,300<br />

participants. In following years the numbers grew. Community support in<br />

organisation and participation was willingly forthcoming. In 1983 the event was held<br />

over 8 days and more than 130,000 visitors attended.<br />

In succeeding years, balancing cultural and commercial participation in Mattara led to<br />

many debates. A downside to commercialism such as show rides in Civic Park was<br />

the damage done to the park, particularly the lawns. A downside to too many cultural<br />

events was limited appeal. Maintaining Mattara’s cultural base has been of<br />

paramount importance as well as providing interest for as wide a group of <strong>Newcastle</strong><br />

people as possible.<br />

22 1960s Civic Park Civic Fountain<br />

Staged landscape improvements for Civic Park began in the 1960s when work started<br />

on the sandstone walls surrounding a RAAF memorial grove near the Laman/Darby<br />

Streets corner. The wall was continued along Laman Street and was completed about<br />

1968.<br />

In early 1961 council called for designs for a fountain for Civic Park and the proposal<br />

submitted by Margaret Hinder of Sydney was selected in September. The work of<br />

building the fountain infrastructure commenced in 1965, the still-water pool designed<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 49

y architects Wilson and Suters and built by <strong>Newcastle</strong> contractor E Hinds Pty Ltd. A<br />

wide pathway and central cenotaph complemented the work.<br />

Water first sprayed from the fountain in September 1966 and an opening ceremony<br />

was held in November. The fountain was named the James Cook Memorial Fountain<br />

in 1970. The fountain completed the link between <strong>City</strong> Hall and War Memorial<br />

Cultural Centre. The formal structure created by this axis is the principal organising<br />

element in the design of Civic Park and the fountain is the modern inspiration for the<br />

city’s identifying graphic icon. Refurbishment of the over 30-year old fountain is a<br />

current project.<br />

23 1960s <strong>–</strong> proposed redevelopment of Civic Theatre<br />

In 1960 the council cleared the debt on the loan borrowed in the mid-<strong>1920s</strong> to<br />

construct the Town Hall and Civic Theatre complex. Proposals were aired about<br />

securing more space for a variety of council needs including office and administrative<br />

space and public lending library facilities. The town clerk predicted that any new<br />

buildings ‘would need to climb skywards’ to use the land to best advantage. 74<br />

A redevelopment proposal was put forward in the early 1960s in response to a<br />

technical advance in the movie industry <strong>–</strong> ‘Cinerama’. From the earliest years the<br />

Civic Theatre was principally used as a cinema under lease to Hoyts Cinemas. Hoyts<br />

engaged an architect Peter Muller to design a new development for the Civic Theatre<br />

complex site, which would provide modern cinema facilities, the additional office<br />

space the council needed and other office space for lease such as to a government<br />

department. Muller, who was influenced by Chinese designs, submitted a 9-storey<br />

‘pagoda’ design. The council supported the proposed development in principal. The<br />

existing block of 14 civic shops was acknowledged as uneconomic use for a valuable<br />

city site.<br />

74 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 1 April 1961<br />

Figure 39: Illustration of a model of a<br />

building proposed by Sydney architect<br />

Peter Muller for erection by <strong>Newcastle</strong><br />

<strong>City</strong> <strong>Council</strong> on the corner of Wheeler<br />

Place and Hunter Street after the Civic<br />

Theatre Block had been demolished.<br />

Source: <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 31<br />

July 1963<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 50

Reaction from the community was varied. The self-interest of Hoyts in the<br />

arrangement caused concern. Those who wanted to keep the Civic for live theatre<br />

were told that the Century Theatre at Broadmeadow was a better option.<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong>’s architects, town planners and others came together to question the<br />

development and the process that led to it. An appeal was made for a civic<br />

masterplan for the future development of the whole area. Too much isolated<br />

development had flowed from the County Plan, it was said. The economics of the<br />

‘pagoda’ plan may have been inadequate to favour its implementation. 75 The<br />

proposal faded from view but the importance of process, planning and community<br />

involvement was dramatically highlighted.<br />

Hoyts lease of the Civic Theatre terminated in 1973. Other cinemas including the<br />

Century at Broadmeadow closed about the same time.<br />

24 1960s <strong>–</strong>a masterplan for civic development<br />

Response to the proposed and isolated ‘pagoda’ development by the <strong>Newcastle</strong><br />

divisions of the Institutes of Town Planning and Architecture included the submission<br />

for public comment of examples of what a masterplan for the whole ‘Civic Centre’<br />

might be. Taken into account were ideas from the County Plan, traffic flow and<br />

management, acquisition of land upon which were deteriorated buildings, and places<br />

for a number of suitable prestige building overlooking Civic Park as centrepiece. One<br />

of the concepts is reproduced here.<br />

Figure 40: A suggested masterplan for the development of the civic block that was presented to the<br />

public in February 1966 and reproduced in the <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 29 February 1966<br />

The Institutes suggested setting up an advisory body comprised of representatives of a<br />

number of <strong>Newcastle</strong> professional, environmental and government organisations.<br />

75 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 3 March, 15 April 1964<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 51

25 Frederick Ash buildings<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> <strong>Council</strong> purchased all the properties of Fred c Ash Limited in 1969. The<br />

purchase provided a foundation for subsequent plans for civic development. At first<br />

the site of the Fred c Ash workshops on the Burwood/King Streets corner was chosen<br />

for the <strong>City</strong> Administration Building, which was in accord with all the masterplans to<br />

that time that focused civic buildings around Civic Park as the civic square.<br />

The Hunter Street facing Menkens designed Fred c Ash building is today recognised as<br />

a significant heritage item protected by a Permanent Conservation Order. The new<br />

Fred c Ash warehouse facing Burwood Street is also significant and both have proved<br />

pivotal to redevelopment plans for the civic precinct. Some awareness of Frederick<br />

Ash and his business and buildings is necessary to understand the part they played in<br />

the commercial history of <strong>Newcastle</strong> from which the heritage values have arisen.<br />

Frederick Ash (1832-1916) was one of <strong>Newcastle</strong>’s leading businessmen and<br />

property owners. His business included hardware, wallpaper, gas fittings and trades<br />

related to the home and commercial building industry. He was born in England in<br />

1832 and arrived in <strong>Newcastle</strong> in 1855. He started in business in a small cottage in<br />

Hunter Street and after a few years moved to larger leased premises on the<br />

King/Brown Streets corner. The business evolved into a brief partnership from 1860<br />

to 1866, then in 1887 a limited liability company.<br />

Importing was the major source of his supplies for which Ash made regular visits<br />

overseas. In the early 1900s one of his sons looked after the London office.<br />

His nephew John Ash (1850-1905) immigrated to <strong>Newcastle</strong> in 1865 and after an<br />

apprenticeship with his uncle commenced in business independently. In the 1870s<br />

John Ash established a timber yard, workshop and sawmills with a shop and dwelling<br />

on land leased from J&A Brown at the side and rear of Mrs Brown’s house and the<br />

Black Diamond Hotel. He probably leased additional land from the AA Company. In<br />

1898 John Ash purchased several portions of this land, on both sides of the Burwood<br />

coal railway and south of the allotments facing Hunter Street. 76<br />

About 1900 Frederick Ash appears to have bought land in this locality and built<br />

premises of his own. In 1901 he called tenders for a building on land that he bought<br />

from John. 77 This land was immediately behind the site of what was to become the<br />

Menkens’ designed building. He subsequently bought this latter site, which was part<br />

of William Andrew Sparke’s earlier purchase. Frederick Menkens designed the 4level<br />

shop, warehouse and office building, which was built during Ash’s absence<br />

overseas in 1904. 78<br />

This building is one of nine warehouses or bond store buildings, which Menkens<br />

designed in central <strong>Newcastle</strong> and one of three completed by him in 1905 in the<br />

Federation warehouse style. The designs of these warehouses helped establish the<br />

characteristic townscape of the commercial centre of <strong>Newcastle</strong>.<br />

John Ash died in <strong>Newcastle</strong> in 1905. 79<br />

76 Godden Mackay, ‘Frederick Ash Building Conservation Plan and Civic Site Archaeological<br />

Assessment’, draft final report, 1992 p. 23<br />

77 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald, 15 June 1901<br />

78 An account of his visit to London is in <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 7 February 1905<br />

79 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 20 and 22 May 1905<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 52

In 1909, two of Frederick Ash’s sons were among the Board of Management of the<br />

company of which Frederick was Managing Director. 80<br />

Frederick Ash died in England in 1915 aged 85 years. Three sons and 5 daughters<br />

survived him. His wife predeceased him. Her death occurred in Switzerland. At the<br />

time of his own death he was travelling to Switzerland. Further research may indicate<br />

more about his connection with Switzerland. Very few details about Frederick Ash’s<br />

life in <strong>Newcastle</strong> have been located. In 1905 he was noted for the hospitality he<br />

extended to British visitors to <strong>Newcastle</strong>. At the time of his death he was recalled as<br />

interested in technical education, having made a generous gift of technical books to<br />

the <strong>Newcastle</strong> School of Arts on his return from overseas in 1905. 81<br />

A survey plan of <strong>Newcastle</strong> city dated 1922 indicate that the Fred c Ash business<br />

occupied a complex of buildings on a significant part of the land between Burwood<br />

and Darby, and Burwood and Hunter Streets. 82 All the buildings between Hunter and<br />

Burwood Streets joined to form an enclosed yard, part of which was ‘covered’.<br />

Between Burwood and Darby Street Fred c Ash had another complex of buildings and<br />

yards.<br />

In September 1925 two Fred c Ash Burwood Street buildings, one of 7-storeys and the<br />

other of 3 or 4 storeys, were destroyed by fire. Property loss was about £80,000.<br />

This was the city’s worst fire since 1908 when the David Cohen warehouse in Scott<br />

Street was lost.<br />

Amid other damage, the walls of the 7-storey building sequentially fell in and the<br />

mass of shattered brickwork strewed Burwood Street for its entire width blocking the<br />

colliery railway line. The fall of the massive counter-weight of the lift in this building<br />

was another ‘awe-inspiring spectacle’. Exploding drums of oil and paint threw out<br />

gushes of ‘polychromatic flame’. Sparks and ashes threatened to set alight a number<br />

of lesser buildings in the vicinity. After the fire, the remaining parts of the buildings<br />

were pulled down.<br />

The city lost a ‘conspicuous structural feature of the city’ - a red brick 7-storey<br />

landmark structure.<br />

The fire led to an inquiry and various reports into the performance of the buildings’<br />

structures, materials used, lifts and so on, and apparently enabled the modification of<br />

building regulation.<br />

A 5-storey rendered brick warehouse facing Burwood Street, known as the ‘new’<br />

Fred c Ash Building, was the work of Pitt and Merewether and erected followed the<br />

1925 fire. Architectural and structural comparison with the fire-destroyed 7-storey<br />

building (well described in the reports at the time of the fire) would be an interesting<br />

study for the evolution of building standards and the <strong>1920s</strong>-1930s approach to fire<br />

risk management. A description of this building in the Godden Mackay report notes<br />

that the interiors reflect ‘comparatively advanced construction’. 83<br />

By 1930 the company had a number of factories in the <strong>Newcastle</strong> district and<br />

branches in Wollongong, Cessnock, Sydney (Leichhardt, Marrickville), and London.<br />

80 Godden Mackay, p. 24<br />

81 <strong>Newcastle</strong> Morning Herald 7 February 1905, 31 October and 1 November 1916<br />

82 Local Studies Library map of <strong>Newcastle</strong> showing buildings and their use LHM B 690/1-4<br />

83 Godden Mackay, …, card 11 of 11, Appendix, not paginated<br />

<strong>Newcastle</strong> Civic and Cultural Precinct History ~ Cynthia Hunter ~ January 2003 page 53

(Later a branch opened at Lismore.) For the next 30 years the business flourished and<br />

it was said that ‘nowhere else was there such a comprehensive hardware store’. 84<br />

The business appears to have specialised in shop fronts and shop fittings in the years<br />

up to the 1930s. This era saw the growth of suburbs and suburban shopping centres<br />

with modern shop fronts reflecting up-to-date marketing trends. The Fred c Ash-<br />

Menkens building itself was significantly altered by the installation of one of these<br />

modern shop fronts. The entrance door was set further into the building and a<br />

showcase window constructed on either side of the created space. Ceramic tiles were<br />

added to the façade and an awning suspended over the footpath. 85<br />

In 1969 the company was take over and became a wholly owned subsidiary of Swans<br />