Cult of beauty - Minerva

Cult of beauty - Minerva

Cult of beauty - Minerva

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

historicity <strong>of</strong> this foundation story, it<br />

was nevertheless widely disseminated<br />

in the ancient Greek world. Writing in<br />

the 5 th century BC, Herodotus refers<br />

to the Argolid antecedents <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Macedonian kings (Histories 8.137–<br />

8), while the poet Euripides (c. 480–<br />

406) composed the tragedy Archelaos<br />

in which the eponymous hero, son <strong>of</strong><br />

king Temenos <strong>of</strong> Argos, was praised as<br />

the founder <strong>of</strong> the city <strong>of</strong> Aegae. Even<br />

the historian Thucydides (c. 460–395<br />

BC) refers to the connection <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Macedonian royal house with the city<br />

<strong>of</strong> Argos (History <strong>of</strong> the Peloponnesian<br />

War 2.10), while at the start <strong>of</strong> the 5 th<br />

century BC the judges at the Olympic<br />

Games also approved the legend <strong>of</strong><br />

the Temenid royal house, allowing the<br />

Macedonian kings to participate in the<br />

Games.<br />

This legendary connection to the<br />

rulers <strong>of</strong> Argos was crucial to the<br />

Macedonian kings, imbuing them<br />

with political and religious authority.<br />

According to divine genealogy,<br />

descendants <strong>of</strong> Temenos could also<br />

claim Heracles, greatest <strong>of</strong> Greek<br />

heroes, as their illustrious ancestor<br />

(Fig 1). Through the demi-god<br />

the Temenids also had familial ties<br />

to Zeus, most powerful <strong>of</strong> the gods.<br />

With such an ancestry, Macedonian<br />

kings could claim to possess the blood<br />

<strong>of</strong> the strongest and most courageous<br />

<strong>of</strong> men, reinforcing their right to lead<br />

their people in both peace and war.<br />

As blood descendents <strong>of</strong> Zeus, their<br />

kingship was also divinely sanctioned<br />

and, in addition to political and military<br />

leadership, they also held the position<br />

<strong>of</strong> high priest, acting as principal<br />

defenders <strong>of</strong> traditional worship. The<br />

mythical pedigree <strong>of</strong> the Temenids<br />

was emphasised through coinage, with<br />

issues from the time <strong>of</strong> Perdiccas II<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2011<br />

3b<br />

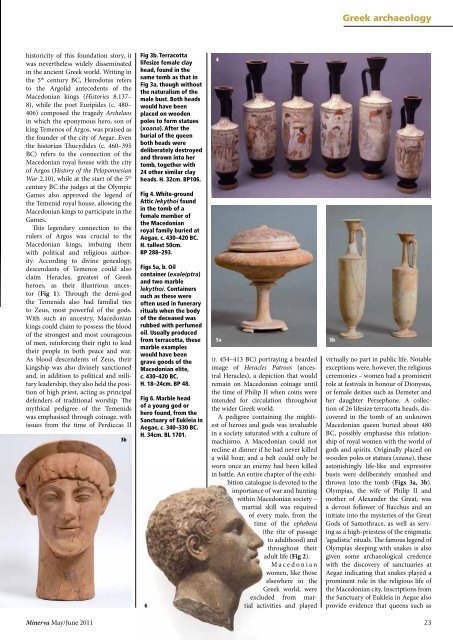

Fig 3b. Terracotta<br />

lifesize female clay<br />

head, found in the<br />

same tomb as that in<br />

Fig 3a, though without<br />

the naturalism <strong>of</strong> the<br />

male bust. Both heads<br />

would have been<br />

placed on wooden<br />

poles to form statues<br />

(xoana). After the<br />

burial <strong>of</strong> the queen<br />

both heads were<br />

deliberately destroyed<br />

and thrown into her<br />

tomb, together with<br />

24 other similar clay<br />

heads. H. 32cm. BP106.<br />

Fig 4. White-ground<br />

Attic lekythoi found<br />

in the tomb <strong>of</strong> a<br />

female member <strong>of</strong><br />

the Macedonian<br />

royal family buried at<br />

Aegae, c. 430–420 BC.<br />

H. tallest 50cm.<br />

BP 288–293.<br />

Figs 5a, b. Oil<br />

container (exaleiptra)<br />

and two marble<br />

lekythoi. Containers<br />

such as these were<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten used in funerary<br />

rituals when the body<br />

<strong>of</strong> the deceased was<br />

rubbed with perfumed<br />

oil. Usually produced<br />

from terracotta, these<br />

marble examples<br />

would have been<br />

grave goods <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Macedonian elite,<br />

c. 430–420 BC.<br />

H. 18–24cm. BP 48.<br />

Fig 6. Marble head<br />

<strong>of</strong> a young god or<br />

hero found, from the<br />

Sanctuary <strong>of</strong> Eukleia in<br />

Aegae, c. 340–330 BC.<br />

H. 34cm. BL 1701.<br />

6<br />

4<br />

5a<br />

(r. 454–413 BC) portraying a bearded<br />

image <strong>of</strong> Heracles Patroos (ancestral<br />

Heracles), a depiction that would<br />

remain on Macedonian coinage until<br />

the time <strong>of</strong> Philip II when coins were<br />

intended for circulation throughout<br />

the wider Greek world.<br />

A pedigree containing the mightiest<br />

<strong>of</strong> heroes and gods was invaluable<br />

in a society saturated with a culture <strong>of</strong><br />

machismo. A Macedonian could not<br />

recline at dinner if he had never killed<br />

a wild boar, and a belt could only be<br />

worn once an enemy had been killed<br />

in battle. An entire chapter <strong>of</strong> the exhibition<br />

catalogue is devoted to the<br />

importance <strong>of</strong> war and hunting<br />

within Macedonian society –<br />

martial skill was required<br />

<strong>of</strong> every male, from the<br />

time <strong>of</strong> the ephebeia<br />

(the rite <strong>of</strong> passage<br />

to adulthood) and<br />

throughout their<br />

adult life (Fig 2).<br />

M a c e d o n i a n<br />

women, like those<br />

elsewhere in the<br />

Greek world, were<br />

excluded from martial<br />

activities and played<br />

5b<br />

Greek archaeology<br />

virtually no part in public life. Notable<br />

exceptions were, however, the religious<br />

ceremonies – women had a prominent<br />

role at festivals in honour <strong>of</strong> Dionysus,<br />

or female deities such as Demeter and<br />

her daughter Persephone. A collection<br />

<strong>of</strong> 26 lifesize terracotta heads, discovered<br />

in the tomb <strong>of</strong> an unknown<br />

Macedonian queen buried about 480<br />

BC, possibly emphasise this relationship<br />

<strong>of</strong> royal women with the world <strong>of</strong><br />

gods and spirits. Originally placed on<br />

wooden poles or statues (xoana), these<br />

astonishingly life-like and expressive<br />

busts were deliberately smashed and<br />

thrown into the tomb (Figs 3a, 3b).<br />

Olympias, the wife <strong>of</strong> Philip II and<br />

mother <strong>of</strong> Alexander the Great, was<br />

a devout follower <strong>of</strong> Bacchus and an<br />

initiate into the mysteries <strong>of</strong> the Great<br />

Gods <strong>of</strong> Samothrace, as well as serving<br />

as a high-priestess <strong>of</strong> the enigmatic<br />

‘agadistic’ rituals. The famous legend <strong>of</strong><br />

Olympias sleeping with snakes is also<br />

given some archaeological credence<br />

with the discovery <strong>of</strong> sanctuaries at<br />

Aegae indicating that snakes played a<br />

prominent role in the religious life <strong>of</strong><br />

the Macedonian city. Inscriptions from<br />

the Sanctuary <strong>of</strong> Eukleia in Aegae also<br />

provide evidence that queens such as<br />

23