Cult of beauty - Minerva

Cult of beauty - Minerva

Cult of beauty - Minerva

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Museum exhibitions<br />

Chris Lightfoot in <strong>Minerva</strong> (January-<br />

Febuary, 2010, pp. 46-9). Chinese art<br />

was largely represented by perishable<br />

objects, such as laquers. Carved ivory<br />

and bone artefacts <strong>of</strong> an ‘Indian’ type<br />

are particularly striking (Figs 6, 7,<br />

8). It has been assumed that because<br />

they depict women and so few men,<br />

they were designed for women’s quarters.<br />

No easily comparable pieces are<br />

known. Stylistically they appear to be<br />

from India, but it is known that artisans<br />

sometimes travelled considerable distances<br />

to practice their craft, and three<br />

uncarved pieces <strong>of</strong> ivory suggest that<br />

the furniture may have been <strong>of</strong> local<br />

manufacture. The glass vessels recovered<br />

from the site all appear to come<br />

from the Mediterranean. Perhaps the<br />

most striking objects from the Roman<br />

portion <strong>of</strong> the treasure consist <strong>of</strong> circular<br />

plaster medallions (Figs 9, 10).<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> the scenes are easily identified<br />

from classical mythology. While similar<br />

depictions are known from other<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> the Roman world, it is rare to<br />

find what would appear to be models<br />

used in a workshop. However, as these<br />

plaster medallions were made with<br />

suspension holes, they were obviously<br />

admired for their own artistic merits.<br />

To return to the original problem,<br />

the excavators originally assumed the<br />

site was the summer capital <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Kushan emperors. Recent scholarship<br />

suggests that while some objects may<br />

28<br />

9<br />

10<br />

Fig 9. Circular<br />

medallion, Begram<br />

Room 13, 1 st century<br />

AD. This depiction<br />

<strong>of</strong> a child with<br />

wings, clutching a<br />

butterfly depicts<br />

Eros and Psyche and<br />

their mystical union.<br />

Aphrodite sent her son<br />

Eros to poison Psyche,<br />

but he fell in love with<br />

her. Diam. 16.5cm.<br />

National Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Afghanistan 04.1.17.<br />

Fig 10. Circular<br />

medallion, Begram<br />

Room 13, 1 st century<br />

AD. Endymion was the<br />

son <strong>of</strong> Zeus and the<br />

nymph Calyce. Selene,<br />

the Titan goddess <strong>of</strong><br />

the moon, asked that<br />

he be granted eternal<br />

youth. According<br />

to the myth he was<br />

granted eternal sleep,<br />

and is visited every<br />

night by Selene in a<br />

cave on Mount Latmos.<br />

National Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Afghanistan.<br />

Diam. 16cm.<br />

Fig 11. Gold clasps,<br />

Tillya Tepe, Tomb III,<br />

second quarter <strong>of</strong> the<br />

1 st century AD. The<br />

figure is <strong>of</strong> a Graeco-<br />

Bactrian soldier, with<br />

a spear and shield.<br />

The figures are not<br />

exactly symmetrical,<br />

as the figure has<br />

the sword hanging<br />

on the left side in<br />

both images. Some<br />

elements, such as the<br />

‘dragon lions’ and the<br />

foliage, harken to the<br />

east for inspiration.<br />

H. 9cm; W. 6.3cm.<br />

National Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Afghanistan 04.40.245.<br />

Archaeology tells a story <strong>of</strong> ancient<br />

Afghanistan as a hub <strong>of</strong> trade, a consumer<br />

<strong>of</strong> the most sumptuous luxury goods, and<br />

an innovator in the arts<br />

have been intended for royalty, the<br />

place where they were stored during<br />

transport may not have been a royal<br />

residence. Chris Lightfoot presents<br />

a convincing case for suggesting the<br />

rooms were part <strong>of</strong> the palace treasury.<br />

With this in mind, the objects<br />

may span several generations, and not<br />

surprisingly for an overland trade hub,<br />

were composed <strong>of</strong> objects from many<br />

different lands.<br />

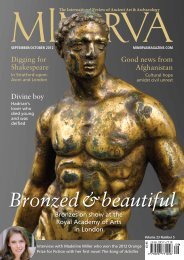

The final culture represented in<br />

the exhibition can be broadly termed<br />

Parthian, although these nomads are<br />

best known further west, from Iran,<br />

Iraq and Turkmenistan. The group,<br />

who left tombs in Tillya Tepe (‘the hill<br />

<strong>of</strong> gold’), show their nomadic heritage<br />

in their mode <strong>of</strong> dress (horseriding<br />

clothing) as well as in their opulent<br />

jewellery. Because <strong>of</strong> their itinerant<br />

lifestyle, status was reflected particularly<br />

in personal adornment. In form<br />

the jewellery is quite varied, but it<br />

shows clearly that while the newcomers<br />

were drawn to the wealth <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Graeco-Bactrian cities, they had their<br />

own artistic cannon. The end result<br />

was unique (Fig 11). This is a period<br />

<strong>of</strong> textual darkness since these newcomers<br />

did not leave many written<br />

records and, for obvious reasons, when<br />

they are noted in Greek annals they<br />

are treated as barbarians. The gold <strong>of</strong><br />

this culture was the focus <strong>of</strong> an earlier<br />

review <strong>of</strong> the exhibition by Dr Dorothy<br />

King in <strong>Minerva</strong> (March-April, 2007,<br />

pp. 9–12).<br />

In sum, this exhibition wonderfully<br />

presents some great treasures from<br />

Afghanistan. But the range <strong>of</strong> materials<br />

touches upon a far wider region and<br />

with trade routes and cultural contacts<br />

ranging from Greece through to India,<br />

the materials could best be described as<br />

a Eurasian treasure. The accompanying<br />

exhibition catalogue details the context<br />

<strong>of</strong> the finds in a number <strong>of</strong> specialist<br />

essays that are best read before seeing<br />

the show. The saga <strong>of</strong> the survival <strong>of</strong><br />

the objects is perhaps the best story:<br />

the keepers <strong>of</strong> these treasures could<br />

easily have sold them so as to live in<br />

comfort in a country free <strong>of</strong> civil war.<br />

They deserve a huge amount <strong>of</strong> gratitude<br />

and remind us that human nature<br />

can be something to be proud <strong>of</strong>. For<br />

the rest <strong>of</strong> us, the exhibition demonstrates<br />

that what was saved is no less<br />

important than what was lost. Humans<br />

have a long history <strong>of</strong> destruction,<br />

but thankfully, there are exceptions to<br />

every rule. n<br />

‘Afghanistan: Crossroads <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Ancient World’ runs at the British<br />

Museum until 3 July. Adults £10,<br />

concessions available. A catalogue,<br />

<strong>of</strong> the same name, edited by Fredrik<br />

Hiebert and Pierre Cambon, is<br />

available, British Museum Press,<br />

2011, 303pp. S<strong>of</strong>tcover, £25.00. For<br />

further information:<br />

Tel: +44 (0)20 7323 8181;<br />

www.britshmuseum.org<br />

11<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2011