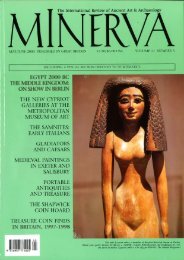

Cult of beauty - Minerva

Cult of beauty - Minerva

Cult of beauty - Minerva

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Museum exhibitions<br />

frescoes <strong>of</strong> subjects from Sir Thomas<br />

Malory’s cycle <strong>of</strong> Arthurian legends,<br />

the Morte D’Arthur. Three densely<br />

detailed watercolours with medieval<br />

subjects painted by Rossetti around<br />

1857 – The Tune <strong>of</strong> Seven Towers, The<br />

Blue Closet (Fig 1) and A Christmas<br />

Carol – directly inspired poems by<br />

Morris and Swinburne. One passionate<br />

enthusiasm common to all<br />

at this time was Edward FitzGerald’s<br />

translation, published in 1859, <strong>of</strong> the<br />

selection <strong>of</strong> 12 th -century poetry attributed<br />

to the Persian polymath Omar<br />

Khayyam (AD 1048–1131). Rossetti<br />

first heard about The Rubáiyát <strong>of</strong> Omar<br />

Khayyám in January 1861 after it had<br />

been remaindered and was on sale<br />

for a penny outside a London bookshop,<br />

at which point he and Swinburne<br />

bought numerous copies, one <strong>of</strong> which<br />

Swinburne presented to Burne-Jones<br />

who produced an illuminated manuscript<br />

<strong>of</strong> the poems (Fig 4).<br />

As the term implies, the Olympians<br />

were hugely successful artists, dominant<br />

at the time. The work <strong>of</strong> Sir<br />

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Edward<br />

Poynter, G.F. Watts and Frederic<br />

Leighton – who became president <strong>of</strong><br />

the Royal Academy in 1879, was created<br />

a baronet in 1886 and became<br />

Lord Leighton just before his death in<br />

1896 – emphasised the classical in both<br />

style and subject matter. Leighton’s The<br />

Syracusan Bride Leading Wild Beasts in<br />

Procession to the Temple <strong>of</strong> Diana (Fig<br />

3) is a monumental canvas inspired<br />

by a passage in the second Idyll <strong>of</strong><br />

44<br />

8<br />

Fig 8. Armchair,<br />

mahogany with cedar<br />

and ebony veneer,<br />

carving and inlay <strong>of</strong><br />

several woods, ivory<br />

and abalone shell,<br />

replaced upholstery.<br />

Sir Lawrence Alma-<br />

Tadema (designer),<br />

Norman Johnstone<br />

& Company (maker).<br />

Fig 9. John Roddam<br />

Spencer Stanhope,<br />

Love and the Maiden,<br />

1877. Tempera, gold<br />

paint and gold leaf<br />

on canvas, Fine Arts<br />

Museums <strong>of</strong> San<br />

Francisco.<br />

Fig 10. ‘Helen <strong>of</strong> Troy’<br />

necklace, gilded<br />

silver and bowenite,<br />

designed by Sir<br />

Edmund Poynter,<br />

made by Carlo<br />

Giulliano, c. 1881.<br />

Loan by American<br />

Friends, V&A Images.<br />

Fig 11. William<br />

Blake Richmond,<br />

Electra at the Tomb<br />

<strong>of</strong> Agamemnon,<br />

1877. Oil on canvas.<br />

Grosvenor Art Gallery<br />

<strong>of</strong> Ontario, Toronto,<br />

Canada.<br />

10<br />

11<br />

Theocritus, ‘And for her then many<br />

other wild beasts were going in procession’.<br />

It depicts some two dozen figures,<br />

each a tribute to the art <strong>of</strong> the past.<br />

A crucial source <strong>of</strong> inspiration for<br />

the Olympians and many <strong>of</strong> their<br />

contemporaries were the Parthenon<br />

Marbles, which had been housed in<br />

the British Museum from 1816 (See<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong>, March/April 2011, p. 9). In<br />

Albert Moore’s A Musician (Fig 2), the<br />

listeners are reminiscent <strong>of</strong> the reclining<br />

figures depicted on the pediments<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Parthenon; in Edward Burne-<br />

Jones’ 1880 work The Golden Stairs<br />

(Fig 7), the maidens move in concert,<br />

like figures circling a Greek vase.<br />

In the 1870s, the leading Aesthetic<br />

artists, Whistler, Leighton, Watts,<br />

Moore and Burne-Jones, evolved a<br />

new kind <strong>of</strong> self-consciously exquisite<br />

painting in which mood, colour, harmony<br />

and <strong>beauty</strong> <strong>of</strong> form were paramount<br />

while subject played little or no<br />

part. In Leighton’s Greek Girls Picking<br />

up Pebbles by the Sea (Fig 5), there is<br />

a discrepancy between the complexity<br />

<strong>of</strong> the figures’ classical drapery and<br />

the triviality <strong>of</strong> their activity, while the<br />

painting compels the viewer to trace<br />

the rhythms <strong>of</strong> the compositional lines,<br />

to follow them, zigzag-fashion, from<br />

one figure to the next into the depth <strong>of</strong><br />

the scene. Similarly, the garden rakes<br />

and the baby juxtaposed with the classical-cum-Regency<br />

gowns in Thomas<br />

Armstrong’s The Hay Field (Fig 6) provide<br />

the reader with intentionally confusing,<br />

anachronistic clues.<br />

9<br />

The opening <strong>of</strong> the Grosvenor<br />

Gallery in 1877 gave the aesthetic<br />

painters a glamorous showcase for<br />

their art. One <strong>of</strong> the most ambitious<br />

paintings at the first Grosvenor exhibition,<br />

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope’s<br />

Love and the Maiden (Fig 9), shows a<br />

reclining female figure who starts, as<br />

if waking from sleep, to encounter a<br />

winged youth with a bow. This might<br />

easily represent the myth <strong>of</strong> Cupid and<br />

Psyche, when Cupid awakens Psyche<br />

from the deathlike slumber into which<br />

she has been cast, having disobeyed<br />

the divine order not to open the casket<br />

she was tasked with retrieving from<br />

the underworld – an aesthetic subject<br />

par excellence, for the casket contained<br />

the secret <strong>of</strong> <strong>beauty</strong>. Yet Stanhope<br />

does not include a casket in his scene,<br />

the work generalises the story, which<br />

could depict any girl’s romantic or sexual<br />

awakening, and the classical associations<br />

are further complicated by<br />

unmistakable allusions to the paintings<br />

<strong>of</strong> Botticelli. Blake Richmond’s<br />

Electra at the Tomb <strong>of</strong> Agamemnon<br />

(Fig 11) draws upon classical tragedy<br />

but displays a stylised vision <strong>of</strong> death<br />

and mourning, avoiding passion and<br />

instead aiming for a compositional<br />

balance and refined colour harmonies.<br />

The rise <strong>of</strong> aestheticism in painting<br />

was paralleled in the decorative<br />

arts by a new and increasingly widespread<br />

interest in the interior design<br />

<strong>of</strong> houses (Fig 13). Many <strong>of</strong> the key<br />

avant-garde architects and designers<br />

worked not only for wealthy clients<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2011