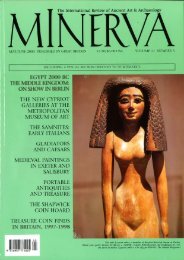

Cult of beauty - Minerva

Cult of beauty - Minerva

Cult of beauty - Minerva

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

12<br />

but also in the reform <strong>of</strong> design for<br />

the middle-class home, as the notion<br />

<strong>of</strong> ‘The House Beautiful’ became a<br />

touchstone <strong>of</strong> cultured life. Attracted<br />

by the growing popularity <strong>of</strong> aesthetic<br />

taste, many <strong>of</strong> the leading firms manufacturing<br />

ceramics, domestic metalwork<br />

and textiles courted artists such<br />

as Walter Crane and a growing band<br />

<strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional designers, most notably<br />

Christopher Dresser. Even the mighty<br />

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema designed<br />

an armchair in the Grecian style (Fig<br />

8) to form part <strong>of</strong> a luxurious suite<br />

<strong>of</strong> furniture, costing £25,000, for the<br />

‘Greek Parlour’ in the New York mansion<br />

<strong>of</strong> Henry Gurdon Marquand, a<br />

highly successful American entrepreneur,<br />

art collector and benefactor.<br />

Archaeological discoveries <strong>of</strong> the<br />

19 th century provided a welcome<br />

new resource for jewellery design.<br />

Connecting with an idealised classical<br />

past, such jewels had a historical<br />

fascination and were exemplars <strong>of</strong><br />

fine metalworking rather than vehicles<br />

for the display <strong>of</strong> massed gemstones<br />

(Fig 14). The Helen <strong>of</strong> Troy necklace<br />

(Fig 10) designed by Poynter to be<br />

worn by the model for his 1881 painting<br />

was a reference to the remarkable<br />

treasure discovered in 1873 by<br />

Heinrich Schleimann during his excavations<br />

at Troy, although its style owes<br />

more to Gujerati design.<br />

In the last decade <strong>of</strong> Queen Victoria’s<br />

reign the Aesthetic Movement entered<br />

its final, fascinating Decadent phase,<br />

characterised by the extraordinary<br />

Archaeological discoveries<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 19 th century provided<br />

a welcome new resource<br />

for jewellery design<br />

Fig 12. Frederic<br />

Leighton, The Bath<br />

<strong>of</strong> Pysche, c.1889–90.<br />

Oil on canvas. © Tate,<br />

London.<br />

Fig 13. George<br />

Aitchison, design for<br />

the interior decoration<br />

<strong>of</strong> the front drawing<br />

room at 15 Berkeley<br />

Square, London, for<br />

F. Lehmann Esq, 1873.<br />

© RIBA library<br />

drawings collection.<br />

Fig 14. Copies or<br />

adaptations <strong>of</strong><br />

archaeological finds<br />

were considered<br />

more artistic than<br />

conventional gem-set<br />

jewellery. This wreath<br />

was a wedding gift to<br />

the future Countess <strong>of</strong><br />

Crawford in 1869. Tiara<br />

<strong>of</strong> gold and pearls.<br />

Castellani, Rome.<br />

© V&A Images.<br />

Fig 15. Harry Bates,<br />

Pandora. Marble,<br />

ivory and bronze,<br />

1890. H. 94cm.<br />

Tate, London.<br />

Fig 16. Icarus, bronze<br />

by Alfred Gilbert,<br />

1884. H 49.5cm.<br />

© National Museums<br />

and Galleries <strong>of</strong> Wales,<br />

Cardiff.<br />

14<br />

black-and-white drawings <strong>of</strong> Aubrey<br />

Beardsley in The Yellow Book. The<br />

V&A exhibition ends with a superb<br />

group <strong>of</strong> the greatest late Aesthetic<br />

paintings, including masterpieces such<br />

as Leighton’s Bath <strong>of</strong> Psyche (Fig 12),<br />

Moore’s Midsummer and Rossetti’s<br />

final picture The Daydream, shown<br />

alongside the sensuous nude figures<br />

sculpted in bronze and precious<br />

materials. Classical prototypes were<br />

abandoned by innovative young sculptors<br />

such as Alfred Gilbert, Edward<br />

Onslow Ford, Harry Bates and other<br />

brilliant younger exponents <strong>of</strong> what<br />

was termed ‘The New Sculpture’. These<br />

artists used both explicit symbols and<br />

subtle suggestion to express intangible<br />

themes <strong>of</strong> love, death or the eternal.<br />

A pr<strong>of</strong>ound stillness and sense<br />

<strong>of</strong> introspective self-absorption is a<br />

recurrent leitmotif in much <strong>of</strong> the New<br />

Sculpture. There is little movement or<br />

drama, but instead a pervasive melancholy,<br />

suggesting the psychological<br />

dimensions <strong>of</strong> the self that dictate fate<br />

or future action. Where classical subjects<br />

are depicted, as in Bates’s Pandora<br />

(Fig 15), the figures are frozen at the<br />

moment before they fulfil their destiny,<br />

becoming archetypes for human frailty<br />

and the complexities <strong>of</strong> the psyche that<br />

dictate behaviour. Frederic Leighton<br />

commissioned a bronze statue, leaving<br />

the choice <strong>of</strong> subject to Gilbert. Icarus<br />

was, at the same time, both a tribute<br />

to Leighton’s well known painting<br />

Daedalus and Icarus, and a chapter in<br />

his series <strong>of</strong> bronzes (Fig 16).<br />

Attempting a definition <strong>of</strong> this<br />

period, the poet and critic Arthur<br />

Symons, a central figure <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Beardsley period and the principal<br />

apologist <strong>of</strong> the decadence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

1890s, wrote: ‘After a fashion it is no<br />

doubt a decadence; it has all the qualities<br />

that mark the end <strong>of</strong> great periods,<br />

the qualities that we find in the<br />

Greek, the Latin decadence; an intense<br />

self-consciousness, a restless curiosity<br />

in research, an over-subtilising refinement<br />

upon refinement, a spiritual and<br />

moral perversity.’ Walter Pater’s philosophical<br />

novel Marius the Epicurean,<br />

published in 1885, is set in the decaying<br />

years <strong>of</strong> the Roman Empire,<br />

reworking in symbolic, philosophical<br />

fictional terms the aesthetic ideals<br />

that he had first adumbrated in his<br />

Renaissance essays. ‘That old pagan<br />

world,’ he wrote, ‘had reached its perfection<br />

in the things <strong>of</strong> poetry and art<br />

– a perfection which indicated only<br />

too surely the eve <strong>of</strong> decline.’ n<br />

‘The <strong>Cult</strong> <strong>of</strong> Beauty: The Aesthetic<br />

Movement 1860–1900’ is at the V&A<br />

until 17 July, tickets £12, concessions<br />

available. A catalogue accompanies<br />

the exhibition, edited by Stephen<br />

Calloway and Lynn Federle Orr,<br />

with essays by Elizabeth Prettejohn,<br />

Penny Sparke and Christopher<br />

Breward: hardback, 288pp, 250<br />

colour photographs, £40. For more<br />

information, please visit www.vam.<br />

ac.uk/cult<strong>of</strong><strong>beauty</strong>.<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2011 45<br />

13<br />

15<br />

16