EXECUTIVE SUMMARY - National Agricultural and Fishery Council ...

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY - National Agricultural and Fishery Council ...

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY - National Agricultural and Fishery Council ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

AFMA – Overall Executive Summary<br />

The AFMA formulators had a gr<strong>and</strong> vision for Philippine agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries.<br />

The seven AFMA principles: (1) poverty alleviation <strong>and</strong> social equity; (2) food<br />

security; (3) rational use of resources; (4) global competitiveness; (5) sustainable<br />

development; (6) people empowerment; <strong>and</strong> (7) protection from competition are<br />

in the right places.<br />

The Philippines is not lacking in visions <strong>and</strong> plans. However, AFMA can be<br />

faulted for over-commitment <strong>and</strong> trying to do many things with too many<br />

agencies, <strong>and</strong> saddled with lack of resources. In the process, it faltered in<br />

implementation. The additional money of P20 billion in the first year (1999); <strong>and</strong><br />

P15 billon a year in the next six years (2000 - 2005) did not materialize.<br />

Moreover, the m<strong>and</strong>ated allocation by component was not observed: there were<br />

relatively more funds for production support <strong>and</strong> far less in marketing, R & D,<br />

human resources <strong>and</strong> inter-agency linkages. In fact, the annual financial flows for<br />

Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Fisheries Modernization Plan (AFMP) declined from 1999 to<br />

2005. In inflation-adjusted terms, the decline would be sharp. In any undertaking,<br />

no program should be launched without assured resources at the right time <strong>and</strong><br />

place. The AFMA is a sad commentary of what a program should not be.<br />

The report is a result of almost two years work – from research <strong>and</strong> interviews to<br />

consultation workshops in 16 regions (up from six areas from inception). The<br />

expansion was to ensure that as many stakeholders are consulted.<br />

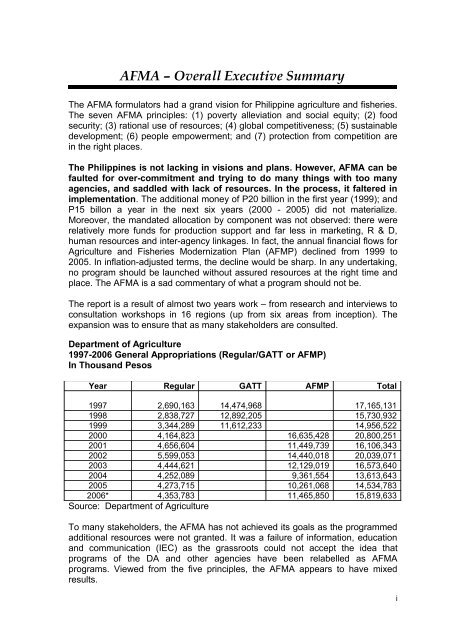

Department of Agriculture<br />

1997-2006 General Appropriations (Regular/GATT or AFMP)<br />

In Thous<strong>and</strong> Pesos<br />

Year Regular GATT AFMP Total<br />

1997 2,690,163 14,474,968 17,165,131<br />

1998 2,838,727 12,892,205 15,730,932<br />

1999 3,344,289 11,612,233 14,956,522<br />

2000 4,164,823 16,635,428 20,800,251<br />

2001 4,656,604 11,449,739 16,106,343<br />

2002 5,599,053 14,440,018 20,039,071<br />

2003 4,444,621 12,129,019 16,573,640<br />

2004 4,252,089 9,361,554 13,613,643<br />

2005 4,273,715 10,261,068 14,534,783<br />

2006* 4,353,783 11,465,850 15,819,633<br />

Source: Department of Agriculture<br />

To many stakeholders, the AFMA has not achieved its goals as the programmed<br />

additional resources were not granted. It was a failure of information, education<br />

<strong>and</strong> communication (IEC) as the grassroots could not accept the idea that<br />

programs of the DA <strong>and</strong> other agencies have been relabelled as AFMA<br />

programs. Viewed from the five principles, the AFMA appears to have mixed<br />

results.<br />

i

1. Poverty alleviation. Agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries grew by almost 3.5 percent<br />

annually between 1999 <strong>and</strong> 2005, its best record since 1970s. However,<br />

rural poverty remains a challenge. The lack of resources for AFMA was<br />

contributory. The non-observance of the criteria for sound allocation of<br />

funds was not also observed, e.g. such as grains vs. tree crops trade-off.<br />

2. Food security. Agriculture growth invariably led to improved food<br />

security. Rice, poultry <strong>and</strong> fishery contributed heavily. Good weather in<br />

the 2000s also helped.<br />

3. Rational use of resources. Allocation of resources from cost-benefit<br />

analysis should be guidepost in investment. However, it appeared that<br />

production support rather than marketing <strong>and</strong> R & D were given priority.<br />

4. Global competitiveness. There were no significant product<br />

breakthroughs in the export market over the past six years. The export<br />

winners' list remained unchanged: banana, pineapple, tuna, seaweeds,<br />

carrageenan, <strong>and</strong> some coconut products. Sugar started to become<br />

competitive.<br />

5. Sustainable development has economic, social <strong>and</strong> environmental<br />

aspects. Public investment decision must be sound to sustain economic<br />

development. For instance, farm incomes, especially for coconut farms,<br />

did not increase as there was little flow of resources. Job creation could<br />

have improved if the enabling environment for private investments was<br />

favorable.<br />

Where will AFMA go from here? Agriculture <strong>and</strong> fishery are the main occupations<br />

in the rural sector. Rural poverty remains high. By government accounts, half of<br />

the rural folks are poor; while 70 percent of the poor reside in the countryside.<br />

Indeed, poverty is an agriculture phenomenon.<br />

The Philippine Farm Sector. In 2005, agriculture <strong>and</strong> fishery produced P 775<br />

billion (in gross value added at current prices). Crops contributed 58 percent,<br />

livestock <strong>and</strong> poultry 22 percent, <strong>and</strong> fishery 15 percent. By crops, palay<br />

provided 16.6 percent; coconut, 5.3 percent; banana, 4.4 percent; corn, 4.3<br />

percent; <strong>and</strong> sugarcane, 2.4 percent. Other crops (tree crops, fruits, vegetables,<br />

etc) had almost 25 percent of total output.<br />

Philippine agriculture is predominantly small, unorganized farm holdings. Crops<br />

occupied most of the farml<strong>and</strong>s. The 2002 Census of Agriculture revealed:<br />

Some 4.8 million (M) farms covering 9.7 M hectares (ha). The average<br />

farm size was 2.0 ha;<br />

Some 40 percent of the farms were less than 1 ha (occupying 8.6<br />

percent of area), 41 percent at 1 ha <strong>and</strong> below 3 ha (31 percent of<br />

area); 10.6 percent between 3 to 5 ha (18.4 percent of area), <strong>and</strong> 6.3<br />

percent, above 5 <strong>and</strong> less than 10 ha (19.8 percent of area). In effect,<br />

about 90 percent of the farmers have less than 5 ha (58 percent of<br />

area);<br />

Some 97 percent were individual farms (94 percent of area); less than<br />

0.2 percent were corporations (2.2 percent of area);<br />

ii

Most were owner-operated. Nearly 79 percent (83 percent of the area)<br />

were owned; less than 13 percent were tenanted (12 percent of area),<br />

2.3 percent leased (2 percent of area); <strong>and</strong><br />

About 67 percent were under temporary crops such as rice <strong>and</strong> corn<br />

(50 percent of area; 35 percent under permanent crops such as<br />

coconut (44 percent of area).<br />

By product, coconut <strong>and</strong> rice farms had more than half of all farms <strong>and</strong> area.<br />

Coconut farms (1.4 M) had slightly higher number than rice farms <strong>and</strong><br />

significantly larger (3.3 M ha vs. 2.5 M ha). Corn, sugarcane <strong>and</strong> other crops<br />

covered over 3 M ha.<br />

Farm L<strong>and</strong>s by Crop: Number of Farms, Farm Size <strong>and</strong> Tenure<br />

Tenure of Parcels (in percent)<br />

Item<br />

No. of Farms<br />

Total No. Owned Tenanted Leased Others<br />

Rice 1,351,678 58.9 23.5 10.8 6.8<br />

Corn 679,183 59.7 21.4 5.2 13.7<br />

Coconut 1,400,394 65.6 19.1 3.4 11.9<br />

Sugarcane 67,490 63.0 12.0 9.6 15.4<br />

Others 1,323,994<br />

All Types 4,822,739 61.4 20.1 5.5 13.0<br />

Area of Farms Total Area (ha) Area Share by Tenure (in percent)<br />

Rice 2,467,164 63.9 23.1 8.3 4.7<br />

Corn 1,354,428 67.1 19.3 5.2 8.4<br />

Coconut 3,325,449 68.8 24.4 2.2 4.6<br />

Sugarcane 362,877 76.0 7.7 11.1 5.2<br />

Others 2,160,875<br />

All Types 9,670,793 67.1 21.3 5.4 6.2<br />

Source: 2002 Census of Agriculture<br />

Fisheries comprised some 1.6 million operators, mostly in subsistence municipal<br />

fishery. Aquaculture is a growing business <strong>and</strong> its potential is high.<br />

Number of Fishing Operators in 2002<br />

No of Operators Share (in percent)<br />

Municipal 1,371,676 85.0<br />

Commercial 16,497 1.0<br />

Aquaculture 226,195 14.0<br />

TOTAL 1,614,368 100.0<br />

Source: 2002 Census of Fisheries<br />

The constituencies of AFMA are the over 11 M workers in 4.8 M farms <strong>and</strong> 1.6 M<br />

fishing operators; <strong>and</strong> the significant millions in the downstream supply chain.<br />

The major challenge is how the DA, LGU <strong>and</strong> related agencies meet the<br />

challenge of millions of small, widely dispersed stakeholders.<br />

Agriculture modernization is an ambitious goal. It took at least 20 years for some<br />

Asian countries to achieve broad-based high agriculture productivity. The<br />

Philippines will need that no less. But to take a high growth path requires<br />

iii

esources <strong>and</strong> judicious resource use. There must be bold initiatives to force the<br />

issue to rational <strong>and</strong> sound criteria rather than business-as-usual political<br />

expediency.<br />

Box 1.<br />

Key Success Factors of Asian Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Fisheries<br />

• Strategic directions that remained unchanged despite changes in political<br />

leadership;<br />

• Continuity in leadership, anchored by a bureaucracy that values professionalism<br />

<strong>and</strong> meritocracy;<br />

• A bureaucracy that is not subject to the vagaries of political leadership;<br />

• A marketing infrastructure that links producers to buyers at reasonable <strong>and</strong><br />

speed;<br />

• A well-budgeted R & D program, accompanied by human resource development<br />

of scientists <strong>and</strong> researchers, that engages universities <strong>and</strong> private sector;<br />

• A market information system with timely, accurate <strong>and</strong> accessible information<br />

• Producers that are mostly organized <strong>and</strong> learned on the dynamics of the market<br />

place – cost, quality <strong>and</strong> supply reliability; <strong>and</strong><br />

• An investment climate that welcomes local <strong>and</strong> overseas investors.<br />

At the same time, the country must launch bold initiatives in R & D investments to<br />

address areas such as productivity, variety, input cost reduction, diversification,<br />

etc in both l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> aqua farming. Data shows that R & D has among the<br />

highest impact on agriculture production <strong>and</strong> poverty alleviation (See below).<br />

Impact of R & D on Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Poverty Reduction<br />

China India Thail<strong>and</strong> Vietnam<br />

Item<br />

Ranking of Returns in Agriculture Production<br />

Agriculture R & D 1 1 1 1<br />

Education 2 3 3 3<br />

Roads 3 2 4 4<br />

Telecommunications 4 - - 2<br />

Irrigation 5 4 5 5<br />

Electricity 6 8 2 -<br />

Soil <strong>and</strong> water<br />

conservation<br />

- 6 - -<br />

Agriculture R & D 2 2 2 2<br />

Roads 3 1 3 4<br />

Education 1 3 4 3<br />

Telecommunication - - - 1<br />

Electricity 4 8 1 -<br />

Irrigation 6 7 5 5<br />

Source: Shenggen Fan (2005). The Role of Agriculture in Poverty Reduction: Evidence<br />

from Asia. IFPRI<br />

iv

There are several principles that must be observed in amending the law <strong>and</strong> its<br />

IRR.<br />

1. A policy environment that delivers a good investment climate. The private<br />

sector is the engine of growth. Some 90 percent of the investments are<br />

made by the private sector. Investment means jobs.<br />

2. Government resources must be leveraged. Thus cost-sharing must be the<br />

order of all programs whether these are from the LGU, education <strong>and</strong><br />

research institutions, industry associations, farmers groups, in cash or in<br />

kind.<br />

3. There must be sound criteria in the use of resources: market-orientation,<br />

<strong>and</strong> social rates of return. This is to correct the disproportionate allocation<br />

to rice to the detriment of other crops, such as tree crops, aquaculture, etc.<br />

There are also many types of irrigation for different crops.<br />

4. Program budgets, particularly marketing support, R & D, infrastructure<br />

(such as farm to market roads, post-harvest facilities, laboratories <strong>and</strong><br />

equipment), irrigation <strong>and</strong> human resource development must be made on<br />

multi-year basis.<br />

5. Protecting the consumer against unsafe, impure <strong>and</strong> fraudulently<br />

presented agriculture <strong>and</strong> fishery products is the foremost responsibility of<br />

a national agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries product control agency.<br />

6. The government must be fully committed to establish structures <strong>and</strong><br />

develop policies to deliver the optimum level of consumer protection. Any<br />

cost recovery scheme implemented to reduce financial burden on the<br />

national government must be carefully evaluated as these costs are often<br />

passed on to the consumers <strong>and</strong> the poor consumers are<br />

disproportionately affected.<br />

7. Stakeholders must be engaged in the planning <strong>and</strong> monitoring of<br />

programs.<br />

8. The DA must focus on the “steering” of agriculture development; while the<br />

LGUs, on the “rowing.” There should be a manual of engagement<br />

between national government (i.e., DA) <strong>and</strong> the LGUs.<br />

v

Box 2.<br />

Stakeholders’ Opinions<br />

A Survey of Stakeholders of 23 key national associations <strong>and</strong> regional agriculture<br />

<strong>and</strong> fisheries council indicated the following:<br />

• Practically all (96 percent) of the respondents were aware of AFMA.<br />

• Two-thirds indicated that AFMA had not achieved modernization of agriculture<br />

<strong>and</strong> fishery.<br />

• Nearly four-fifths (78 percent) indicated that AFMA had not enhanced profits<br />

<strong>and</strong> incomes.<br />

• About four in five respondents (78 percent) indicated that AFMA has not<br />

ensured accessibility, availability <strong>and</strong> stability of food supply.<br />

• Some three in five (57 percent) of the respondents answered that AFMA has<br />

not encouraged horizontal <strong>and</strong> vertical integration in agriculture.<br />

• Two thirds (65 percent) of the respondents indicated that AFMA failed to<br />

strengthen peoples’ organizations, cooperatives <strong>and</strong> NGOs; did not agree that<br />

AFMA has enhanced the comparative advantage of the agriculture <strong>and</strong><br />

fisheries sectors; <strong>and</strong> felt that AFMA failed to induce the agriculture <strong>and</strong><br />

fisheries sectors to ascend continuously.<br />

• About half (52 percent) felt that AFMA was unable to promote industry<br />

dispersal.<br />

• Nearly three quarters (74 percent) responded that AFMA was not able to<br />

provide safety nets.<br />

• Two thirds (65 percent) of the respondents felt that AFMA was not able to<br />

improve their quality of life.<br />

• Seven out of ten respondents were not satisfied with AFMA performance.<br />

• Nearly three in five respondents (57 percent) indicated awareness of the<br />

AFMP.<br />

• Most of the respondents felt “not satisfied” with AFMP implementation.<br />

Box 3.<br />

Regional Stakeholders Opinions<br />

Some 724 participants in 16 regions responded to the five overarching questions<br />

prior to the start of the workshop.<br />

• Nearly 90 percent were aware of the AFMA;<br />

• About 68 percent answered positively that AFMA helped agriculture/industry.<br />

Large majorities were recorded in all regions, except Central Mindanao;<br />

• Two-thirds showed awareness of the Strategic Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Fisheries<br />

Development Zones (SAFDZ) in their respective areas;<br />

• Barely 40 percent were satisfied with SAFDZ implementation. Only four regions<br />

showed high levels of satisfaction: Ilocos, Cagayan Valley, Central Luzon <strong>and</strong><br />

Southern Mindanao; <strong>and</strong><br />

• They cited that the major concerns on AFMA were: information dissemination,<br />

implementation, budget, <strong>and</strong> duration.<br />

vi

The 724 regional workshops participants were asked to rank the AFMA<br />

components according to their priorities. The national average (the simple<br />

average of the 16 regions) showed their main priorities were: irrigation,<br />

marketing, other infrastructure (e.g. farm-to-market roads), post harvest facilities<br />

<strong>and</strong> credit. However, the priorities varied considerably across the 16 regions<br />

Ranking of Priority Sectors of AFMA Components: Philippine Average<br />

Component/<br />

Region<br />

Irrigation 3.2 1<br />

Credit 4.2 5<br />

Marketing 3.5 2.5<br />

Post-harvest 3.6 4<br />

Other Infrastructure 3.5 2.5<br />

Education 7.1 6<br />

Information Support 7.5 8<br />

Product St<strong>and</strong>ards 8.1 10<br />

Extension 9.2 11<br />

Trade 7.4 7<br />

R & D 8.0 9<br />

Average<br />

16 Regions Rank Remarks<br />

The average ranks of 16 regions<br />

indicated close support for each<br />

of the top 5 components.<br />

Irrigation l<strong>and</strong>ed on top but<br />

marketing, other infrastructure,<br />

<strong>and</strong> post harvest were not far<br />

behind.<br />

Luzon ranked irrigation, post harvest, marketing support, credit <strong>and</strong> other<br />

infrastructure as major priorities. However, CAR ranked marketing as Priority No.<br />

1.<br />

Priority Sectors of AFMA Components: LUZON<br />

Component/<br />

Region CAR 1 2 3 4-A 4-B 5 Ave.<br />

Cluster<br />

Rank<br />

Irrigation 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1.1 1<br />

Credit 3.5 2 3 3 5 5 3 3.5 4<br />

Marketing 1 3 2 4 4 4 4 3.1 3<br />

Post-harvest 3.5 4 4 2 2 2 2 2.8 2<br />

Other Infrastructure 5.5 6.5 5.5 5 3 3 5 4.8 5<br />

Education 5.5 6.5 9.5 11 10 6 9 8.2 10<br />

Information Support 7 6.5 7 9 8.5 7.5 8 7.5 7<br />

Product St<strong>and</strong>ards 8.5 6.5 8 7.5 7 7.5 10 8.1 9<br />

Extension 8.5 11 11 10 11 10 6 9.2 11<br />

Trade 10 10 9.5 7.5 6 9 7 7.4 6<br />

R & D 11 6.5 5.5 6 8.5 11 11 8.0 8<br />

vii

In the Visayas, the top priorities were: irrigation, credit, other infrastructure,<br />

marketing support, <strong>and</strong> post harvest facilities. Central Visayas rated other<br />

infrastructure as higher priority than irrigation.<br />

Priority Sectors of AFMA Components: VISAYAS<br />

Component/<br />

Region 6 7 8 Ave. Cluster Rank<br />

Irrigation 1 2 1 1.3 1<br />

Credit 3.5 5 2.5 3.7 2.5<br />

Marketing 5.5 4 5 4.8 4<br />

Post-harvest 3.5 3 11 5.8 5<br />

Other Infrastructure 2 1 8 3.7 2.5<br />

Education 9 11 2.5 7.5 8.5<br />

Information Support 11 9 7 9.0 9.5<br />

Product St<strong>and</strong>ards 10 7 10 9.0 9.5<br />

Extension 7 10 4 7.0 7<br />

Trade 8 6 6 6.7 6<br />

R & D 5.5 8 9 7.5 8.5<br />

Mindanao’s priorities differed from the rest of the country. Its top five were: other<br />

infrastructure, marketing support, post harvest facilities, credit <strong>and</strong> education.<br />

Irrigation copped the top slot only in Western Mindanao <strong>and</strong> Southern Mindanao.<br />

It rated low in Northern Mindanao, Central Mindanao, Caraga <strong>and</strong> ARMM. By<br />

contrast, other infrastructure rated No. 1 in Northern Mindanao, Southern<br />

Mindanao, Central Mindanao <strong>and</strong> ARMM.<br />

Priority Sectors of AFMA Component: MINDANAO<br />

Component/<br />

Region 9 10 11 12 Caraga ARMM Ave.<br />

Cluster<br />

Rank<br />

Irrigation 1 7 1 11 11 8.5 6.6 7<br />

Credit 4 11 4 3.5 4 5 5.3 4<br />

Marketing 5.5 2 2 1.5 1.5 7 3.3 2<br />

Post-harvest 2 3 3 3.5 7 2.5 3.5 3<br />

Other<br />

Infrastructure 3 1 1 1.5 4 1 1.9 1<br />

Education 9 7 7 6 1.5 2.5 5.5 5<br />

Information Support 7 7 8 5 8.5 4 6.6 7<br />

Product St<strong>and</strong>ards 8 9.5 6 8 6 10 7.9 9<br />

Extension 11 9.5 10 10 10 8.5 9.8 10<br />

Trade 5.5 5 10 9 4 6 6.6 7<br />

R & D 10 4 5 7 8.5 11 7.6 9<br />

The principal lesson: regional priorities vary. So far, irrigation (primarily for<br />

rice) had the largest budget share at 30 percent but in fact, rice comprised less<br />

than 30 percent of farms, 17 percent of gross value added in agriculture <strong>and</strong><br />

fisheries, <strong>and</strong> 17 percent of gross farm value. In the process, development of<br />

deserving farm products was stifled due to lack of rational allocation criteria.<br />

Irrigation must also include high value crops.<br />

viii

KEY PROPOSALS<br />

A. Full Implementation of the Law<br />

1. The major recommendation is to ensure funding. The incremental budget of<br />

P15-20 billion a year over the pre-AFMA should be implemented. This<br />

means a budget level today of P31 to 36 billion a year versus less than P16<br />

billion in 2006.<br />

2. Secondly, the percentage allocation by component as m<strong>and</strong>ated by AFMA<br />

must be followed at the very least.<br />

3. As provided by the law, the Department of Agriculture should formulate <strong>and</strong><br />

implement a medium <strong>and</strong> long term comprehensive Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Fisheries<br />

Modernization Plan in consultation with various stakeholders including all<br />

concerned government agencies <strong>and</strong> considering regional priorities.<br />

4. Market prospects should determine the balance between food <strong>and</strong> non-food<br />

crops (grains <strong>and</strong> tree crops) <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>-based <strong>and</strong> water (sea) based farming.<br />

5. The project/program spending must be subject to sound economic <strong>and</strong> social<br />

criteria.<br />

6. The budget releases will have multi-year components in order not to<br />

jeopardize long-gestating projects such as R & D, <strong>and</strong> tree crops. Using one<br />

percent of agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries gross value added as benchmark, the<br />

current budget for R &D should be in the order of P 8.5 billion in 2006. The 10<br />

percent AFMA allocation for R & D appears inadequate using the benchmark.<br />

7. There should be a working Program Benefit Monitoring <strong>and</strong> Evaluation<br />

System (PBMES) of the AFMP as provided for by Section 18 of AFMA <strong>and</strong> its<br />

IRR.<br />

8. A broad based monitoring system under the NAF <strong>Council</strong> should be designed<br />

<strong>and</strong> implemented to assess the effective implementation of the AFMA.<br />

B. Amendments to the Law<br />

General<br />

1. Section 2 (Declaration of Policy). The proposed wording will be:<br />

The State shall promote an enabling environment that encourages investments.<br />

The State recognizes the critical role of private investment in growth <strong>and</strong><br />

job creation.<br />

2. Section 3 (Statement of Objectives). Proposed additions:<br />

To promote private investment as a prime vehicle of job creation <strong>and</strong> rural<br />

industrialization.<br />

ix

To ensure that allocation of resources are based on sound economic, social <strong>and</strong><br />

environmental criteria.<br />

3. Section 111 (General Provisions). Budget allocations by component must<br />

reflect regional priorities.<br />

C. Proposals by Component<br />

To fully appreciate the full significance of the Report, readers are strongly<br />

encouraged to read the main findings <strong>and</strong> recommendation in the Chapter<br />

Summaries of the individual AFMA Components.<br />

1. Marketing Support <strong>and</strong> Information (Sections 38-45)<br />

Ensure that AFMA provisions will:<br />

(a) Secure the m<strong>and</strong>ated 8 percent of the total AFMP budget. The focus will<br />

be diversification of the regions, product development, export market<br />

intelligence, <strong>and</strong> participation in trade fairs with cost-sharing;<br />

(b) Revisit the 30 percent allocation to irrigation in regions where rice is not<br />

the major economic base; <strong>and</strong><br />

(c) Support the operation of an exp<strong>and</strong>ed network of agriculture (<strong>and</strong><br />

fisheries) attaches.<br />

Amendments<br />

(a) Section 41 (NIN). Focus resources to complete the linkage of DA<br />

agencies <strong>and</strong> national research institutions<br />

(b) Section 42 (Information <strong>and</strong> Marketing Service). Exp<strong>and</strong> data collection<br />

coverage <strong>and</strong> frequency by product at the municipal <strong>and</strong> barangay levels;<br />

<strong>and</strong><br />

(c) New Section. The national <strong>and</strong> local governments will promote costsharing<br />

with the private sector on agriculture <strong>and</strong> fishery projects such as<br />

access infrastructure, irrigation, R & D, etc.<br />

Revisions to IRR<br />

(a) AMAS. Rule 40.6. AMAS will have an exp<strong>and</strong>ed role (See Chapter<br />

Summary)<br />

(b) NIN. Rule 111.5.10 provides that 4 percent of the AFMP will be for the<br />

<strong>National</strong> Information Network. Given the recent developments in ICT, the<br />

NIN should instead focus on linking DA regional offices as well as various<br />

research institutions with new cost-effective technologies. Linkages with<br />

LGUs must be at their initiative <strong>and</strong> on a cost-sharing basis.<br />

(c) ITCAF. Rule 44.1 Taking advantage of the recent ICT, it will: (a) complete<br />

linkages at the regional level of all agriculture agencies using low cost<br />

internet technologies. The LGU who wish to be connected must costshare;<br />

<strong>and</strong> (b) accredit universities as repository of commodity information<br />

(market, farm technology <strong>and</strong> economics, value adding, etc.) along the<br />

lines of the USDA model.<br />

x

(d) BAS Rule 44.1 BAS must be provided with adequate resources under its<br />

new m<strong>and</strong>ate of exp<strong>and</strong>ed data generation relevant to commodities, rural<br />

incomes <strong>and</strong> consumption patters (See Chapter Summary).<br />

(e) AFIS. Rule 42.1. This report supports the transformation of AFIS into a<br />

Corporate Communication Office of the DA.<br />

(f) NMAP Rules 40.4 – 40.5. Considering that the NMAP has little relevance<br />

in a globally competitive market, its mission should be delegated to the<br />

producer groups <strong>and</strong> supply chain players.<br />

(g) NMU. Rule 40.7 There is needed to revisit the “big roles” of NMU. The<br />

AFMA support is better used under cost-sharing schemes with industry<br />

associations <strong>and</strong> farmers’ associations in building their competitive<br />

intelligence capability. It is proposed that a private sector-led Agri-fishery<br />

Marketing Advisory <strong>Council</strong> be convened as <strong>and</strong> when needed. The High<br />

<strong>Council</strong> will be composed of presidents of leading industry associations.<br />

(h) DA Research Service (Policy Analysis Service) will emulate the model of<br />

the USDA Economic Research Service.<br />

(i) <strong>Agricultural</strong> Attaches Rule 42.4. The Attaches must be provided with<br />

adequate resource to network with industry players overseas, assemble<br />

timely <strong>and</strong> accurate information, <strong>and</strong> conduct/ purchase market <strong>and</strong><br />

strategic country studies. The proposals are to: increase by at least 50<br />

percent the number of agriculture attaches by 2010; <strong>and</strong> benchmark<br />

attaché numbers, tasks <strong>and</strong> budgets with ASEAN nations.<br />

(j) Capability Building. Rule 111.5.7 provides that 5 percent of the AFMP<br />

budget will be for capability building for scholarships, technical upgrading<br />

<strong>and</strong> training, etc. This should include capability building for marketing,<br />

market research, market studies, supply chain <strong>and</strong> benchmarking, etc.<br />

2. Trade <strong>and</strong> Fiscal Incentives (Sections 108-110)<br />

The recommendations are as follows:<br />

(a) Pursuance of a more vigorous macro <strong>and</strong> sub-sectoral policy<br />

reforms <strong>and</strong> law enforcement relative to agricultural trade, to enhance<br />

the evolving gains in export competitiveness during AFMA implementation<br />

period. Enforcement of existing laws (e.g. anti-smuggling, quarantine) <strong>and</strong><br />

enhancement of domestic support measures to gain competitiveness are<br />

in the right directions.<br />

(b) Continue stronger trade negotiation initiatives with other members of<br />

the LDCs (Group of 20, Group of 33 <strong>and</strong> AFTA) of WTO to level the<br />

playing field in agricultural trade. This implies strengthening of the Policy<br />

Analysis Division of DA to backstaff trade negotiations.<br />

(c) Assist small-medium enterprises <strong>and</strong> cooperatives in the regions to<br />

avail of tariff exemptions of imported agricultural inputs, to enhance their<br />

competitiveness in the export market. The feasibility of removing all forms<br />

of tariff that constrains agricultural modernization should be explored as a<br />

policy.<br />

(d) Revisit the ACEF, extend its economic life if necessary, <strong>and</strong> study<br />

alternative strategies to make it more effective as an enhancing<br />

mechanism to global competitiveness in the agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries<br />

sector;<br />

xi

(e) Reprioritize the remaining budget of ACEF so that it can provide<br />

funding for strategic public investments closest to the major project areas<br />

of already ongoing ACEF projects <strong>and</strong> allocate grants to special projects<br />

for technical assistance (feasibility studies, management guidance, etc)<br />

among small farmers’ organizations <strong>and</strong> cooperatives applying for funding<br />

under ACEF Facility.<br />

(f) Revisit the implementation mechanisms of ACEF to separate the policy<br />

<strong>and</strong> oversight functions with the management /implementation of the<br />

facility.<br />

(g) Trade issues should be integrated in the national development<br />

agenda, especially those related to poverty reduction, increasing<br />

productivity <strong>and</strong> competitiveness, providing compensation <strong>and</strong> human<br />

development safeguards, <strong>and</strong> diversification of exports <strong>and</strong> markets. At<br />

the regional / international development levels, trade issues should build<br />

credible alliances, achieve fairer terms of trade, target technical<br />

assistance, strengthen the special <strong>and</strong> differential treatment (SDT)<br />

provisions of the WTO Agreement, offer aid for trade <strong>and</strong> focus on human<br />

development.<br />

3. Irrigation <strong>and</strong> SAFDZ (Sections 5-12; 26-37)<br />

The review points to one main conclusion, that is, irrigation <strong>and</strong> SAFDZ<br />

components were not implemented! Four general sets of recommendations were<br />

formulated for the effective <strong>and</strong> speedy implementation of the irrigation <strong>and</strong><br />

SAFDZ components of AFMA. These include the following:<br />

(a) Jump starting the implementation of stipulations <strong>and</strong> their corresponding<br />

IRRs that are within the capability of existing institutions <strong>and</strong> institutional<br />

mechanisms to carry out.<br />

In more than half of the IRRs, there was no compliance due to inaction<br />

or indifference of the agencies concerned. These include rules under<br />

Section 26 to 30.<br />

(b) Amending sections <strong>and</strong> IRRs of AFMA for clarity of objectives, targets,<br />

budgetary provisions, adequacy of baseline information <strong>and</strong> institutional<br />

mechanisms, <strong>and</strong> realistic time frames.<br />

The stipulations <strong>and</strong> IRRs are beyond the capability of the concerned<br />

institutions <strong>and</strong> individuals to accomplish within the specified time<br />

frames of AFMA activities. They should be reviewed for clarification of<br />

budget, objectives, <strong>and</strong> targets, amendments in terms of more realistic<br />

time frames, <strong>and</strong> data adequacy as well as institutional arrangements,<br />

strengthening, <strong>and</strong> reorganization. These include m<strong>and</strong>ates under<br />

Sections 5 <strong>and</strong> 9.<br />

(c) A Program Framework for Accelerated <strong>and</strong> Sustained Irrigation<br />

Development.<br />

The Team Expert has formulated a framework that is still very relevant<br />

today in his book Averting the Water Crisis in Agriculture: Policy <strong>and</strong><br />

xii

Program Framework for Irrigation Development (David, 2003). This<br />

includes a strategic vision for the transformation of high-risk, rainfed<br />

agriculture into highly productive, intensive <strong>and</strong> diversified irrigated<br />

agriculture.<br />

(d) A procedure for the identification of NPAAAD, SAFDZ, <strong>and</strong> model farms<br />

based on the stipulated criteria <strong>and</strong> implementation of the SAFDZ<br />

concept has been proposed.<br />

The root cause of the non-compliance with the SAFDZ concept was<br />

flawed process of delineating the SAFDZ. There is an urgent need to<br />

accurately <strong>and</strong> expediently delineate the SAFDZ on the basis of the<br />

criteria stipulated by the Act (Section 6 <strong>and</strong> its IRR).<br />

4. Credit (Sections 20-25)<br />

The following are recommended:<br />

(a) To address the lack of investment credit:<br />

• Strengthen L<strong>and</strong> Bank’s capacity to evaluate <strong>and</strong> finance long-term<br />

projects; <strong>and</strong><br />

• Promote collaboration among GFIs <strong>and</strong> private banks/business <strong>and</strong><br />

the farming community to develop appropriate loan products <strong>and</strong><br />

services for long-term projects<br />

(b) To help resolve the inadequate financing of smallholder.<br />

• Re-examine lending policies, processes <strong>and</strong> products of L<strong>and</strong> Bank<br />

<strong>and</strong> Quedancor, e.g. wholesale <strong>and</strong> retail lending, participation of<br />

rural financial institutions<br />

(c) To address the missing market for finance services:<br />

• Identify barriers or constraints <strong>and</strong> devise incentives for investors <strong>and</strong><br />

lenders; <strong>and</strong><br />

• develop innovative pilot projects to improve access to formal lending<br />

(d) To minimize the systemic risks in the rural areas:<br />

• Introduce a better package of risk-reducing instruments, e.g., critical<br />

rural infrastructure, access to research <strong>and</strong> development, technology<br />

<strong>and</strong> information.<br />

(e) To help small farmer access to the global supply chains.<br />

• Provide technical assistance to small farmers/rural producers;<br />

• Provide budgetary appropriations for critical rural infrastructure <strong>and</strong><br />

other support services<br />

• Link agricultural primary producers with agro-processors, agri-<br />

businesses, marketing agents, etc.<br />

(f) To mitigate the impact of agrarian reform on l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> credit markets:<br />

• Re-examine policies affecting l<strong>and</strong> market transactions<br />

xiii

5. Other Infrastructure <strong>and</strong> Post-harvest Facilities (Sections 46-59)<br />

The general recommendations:<br />

(a) Finalize an integrated agriculture <strong>and</strong> fishery infrastructure plan.<br />

The plan will serve as the blue print in identifying priority post-harvest<br />

facilities, farm-to-market roads, research <strong>and</strong> technology infrastructure,<br />

<strong>and</strong> other implementing mechanism based on effective organizing<br />

frameworks by the DA-concerned agencies in partnership with LGUs<br />

during the period of AFMA extension. The DA should also coordinate with<br />

the officials of DAR <strong>and</strong> DENR to determine the convergence of FMRs<br />

<strong>and</strong> other related infrastructure.<br />

(b) Review <strong>and</strong> finalize the guidelines for the prioritization of<br />

government resources for the other infrastructure <strong>and</strong> post-harvest<br />

facilities. DA-FOS, BPRE <strong>and</strong> DA-PDS have initially prepared the<br />

guidelines for prioritization of government resources for the other<br />

infrastructure <strong>and</strong> post-harvest facilities. In view of the extension of<br />

AFMA, DA-OSEC <strong>and</strong> concerned agencies must review the said<br />

guidelines to determine whether these are still relevant given the<br />

changing needs of the agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries sector, <strong>and</strong> if not<br />

formulate a more appropriate guidelines/criteria.<br />

(c) Designate a Department Assistant Secretary to take charge of agrifisheries<br />

infrastructure. Rule 46.2 of AFMA states that the DA<br />

Secretary should designate a DA Assistant Secretary to take charge of<br />

the DA’s program of infrastructure support for agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries<br />

modernization. At present, there is no DA Assistant Secretary assigned<br />

to assume such function.<br />

(d) Institutionalize the agricultural engineering groups of DA <strong>and</strong> LGUs.<br />

The agricultural engineering groups of DA <strong>and</strong> LGUs which have been<br />

existing for so long should be mainstreamed in the DA structure <strong>and</strong><br />

LGUs to effectively <strong>and</strong> efficiently provide the necessary technical <strong>and</strong><br />

engineering support in the implementation of agri-fishery infrastructure<br />

<strong>and</strong> mechanization projects under AFMA as well as in the provision of the<br />

needed assistance by farmers concerning the operation <strong>and</strong><br />

maintenance of their post-harvest facilities <strong>and</strong> machinery projects.<br />

(e) Enforce <strong>and</strong> continue developing the Philippine agricultural<br />

engineering st<strong>and</strong>ards. Although the DA has already adopted five<br />

volumes of the Philippine agricultural engineering st<strong>and</strong>ards, these<br />

should be fully enforced as part of the implementation of agri-fisheries<br />

infrastructure, mechanization <strong>and</strong> post-harvest facilities projects.<br />

Likewise, other st<strong>and</strong>ards particularly on the machineries <strong>and</strong> agricultural<br />

facilities for other agricultural <strong>and</strong> fishery commodities which are not yet<br />

existing should also be developed. This will address the issues <strong>and</strong><br />

problems on low quality, subst<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>and</strong> underutilization of post-harvest<br />

xiv

facilities, slaughterhouses, farm machineries <strong>and</strong> other agri-fisheries<br />

facilities.<br />

(f) Design <strong>and</strong> implement an effective monitoring system for AFMA.<br />

Although there is a monitoring scheme suggested for FMRs <strong>and</strong><br />

expectedly for post-harvest facilities <strong>and</strong> agricultural machinery, it is<br />

important that NAFC will serve as the overall agency responsible for<br />

integrating the progress reports submitted by concerned agencies <strong>and</strong><br />

monitoring of other infrastructure that has no designated DA-agency to<br />

assume such function. It is important to allocate a regular budget of at<br />

least 1 percent of the total budget to be earmarked for other infrastructure<br />

<strong>and</strong> post-harvest facilities for monitoring purposes. A consultant may be<br />

hired to assist in the design of the monitoring system for other<br />

infrastructure <strong>and</strong> post-harvest facilities.<br />

The specific recommendations include:<br />

(g) Continue the implementation of the counterpart-funding scheme between<br />

the LGUs <strong>and</strong> the national government for FMR<br />

construction/rehabilitation as stipulated in the IRR.<br />

(h) Involve the target beneficiaries in the construction/rehabilitation <strong>and</strong><br />

maintenance of FMRs.<br />

(i) Adopt the proposed amendments/addendum on the existing policy<br />

guidelines on FMR development.<br />

(j) Conduct policy studies on shipping services.<br />

(k) Assess the state of telecommunication services for agro-industry.<br />

(l) Fast-track the validation, approval, <strong>and</strong> adoption of the Action Plan on<br />

quarantine <strong>and</strong> regulatory services.<br />

(m) Finalize the program that will encourage the LGUs to turn over the<br />

management <strong>and</strong> operation of public markets <strong>and</strong> abattoirs to qualified<br />

vendors’ or suppliers’ cooperatives.<br />

(n) Develop a national post-harvest development plan.<br />

(o) Fast-track the passage of the agricultural <strong>and</strong> fishery mechanization law<br />

(p) Provide adequate training <strong>and</strong> extension support<br />

(q) Continue conducting the nationwide post-harvest facility <strong>and</strong> agricultural<br />

machinery inventory.<br />

6. Budget (Sections 111-112)<br />

The following recommendations are put forward:<br />

(a) DA to define its Strategic Priorities consistent with its core<br />

functions under the AFMA. For a more efficient use of its limited<br />

resources, the DA needs to clearly define its strategic priorities <strong>and</strong> make<br />

them consistent with its core functions under the AFMA. It should be able<br />

to direct its resources in the performance of its m<strong>and</strong>ated functions<br />

through a transparent financial budget. The rationalization program of the<br />

national government is a major enabling milestone for the DA to fine tune<br />

the agriculture bureaucracy to meet the challenges posed by the AFMA.<br />

xv

(b) DA to implement budget reform measures. DA has started instituting<br />

measures in accordance with the principles of public expenditures<br />

management reforms espoused by the DBM. New budget formats that<br />

will enable the DA to structure its budgetary allocation in accordance with<br />

its Major Final Outputs (MFO) had been started. These new formats<br />

should facilitate the reconciliation of authorized expenditures with their<br />

MFOs, <strong>and</strong> consequently their priority areas for spending.<br />

(c) DA to institutionalize agency-wide reforms. The effective<br />

implementation of the World Bank-assisted Diversified Farm Income <strong>and</strong><br />

Market Development Project should provide the much needed boost to<br />

the institutionalization of reforms. This execution of the five interlinked<br />

components should bolster an agency-wide change <strong>and</strong> development<br />

process.<br />

(d) Budget allocation priorities to take into account results of regional<br />

consultations.<br />

(e) DA to enjoin more active participation by the private sector <strong>and</strong><br />

LGUs. The DA’s major role should be to encourage private sector<br />

investments that would dynamically induce agricultural development <strong>and</strong><br />

modernization. It should concentrate on providing a more conducive<br />

policy environment for the private sector initiatives to thrive. Also,<br />

concentration on major infrastructure development, outside the ambit <strong>and</strong><br />

financial reach of the private sector, would result in improved symbiotic<br />

relationship between government <strong>and</strong> private sector.<br />

(f) DA to reconcile its records with the DBM. It is important that efforts be<br />

made by the DA to reconcile its records with that of the DBM. This should<br />

include all the other records pertaining to fund attributions to the AFMA<br />

special funds. The effect of not using the same set of data when<br />

requesting (on the part of the DA) <strong>and</strong> analyzing <strong>and</strong> deciding on the<br />

budget approvals <strong>and</strong> fund releases (on the part of the DBM) cannot be<br />

overemphasized.<br />

7. Product St<strong>and</strong>ardization <strong>and</strong> Consumer Safety (Sections 60-64)<br />

Proposed Amendments<br />

AFMA Chapter 7, Product St<strong>and</strong>ardization <strong>and</strong> Consumer Safety, should be<br />

amended to strengthen the agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries product control, promote<br />

uniform application of consumer protection measures, more timely action to<br />

protect consumers <strong>and</strong> more cost efficient <strong>and</strong> effective use of resources <strong>and</strong><br />

expertise. The AFMA IRR <strong>and</strong> related AOs will have to be amended as well.<br />

(a) The first proposed amendment is to provide for the establishment of<br />

the Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Fisheries Safety Authority (AFSA). AFSA shall<br />

integrate the agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries safety <strong>and</strong> quality system to<br />

achieve effective collaboration <strong>and</strong> coordination among the different<br />

agencies of DA, DOH, DTI <strong>and</strong> LGUs.<br />

xvi

(b) The second proposed amendment concerns the function <strong>and</strong><br />

organization of BAFPS. BAFPS should be made the sole st<strong>and</strong>ards<br />

formulation agency of government in the agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries sector.<br />

BAFPS will formulate new st<strong>and</strong>ards, <strong>and</strong> review <strong>and</strong> update existing<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ards to harmonize them with international st<strong>and</strong>ards.<br />

(c) The third proposed amendment is the establishment of a Laboratory<br />

Service at the same level as BAFPS <strong>and</strong> the Inspection <strong>and</strong> Regulatory<br />

Service. The LS will be the new management structure for all<br />

laboratories (more aptly referred to as “service laboratories”) <strong>and</strong> a<br />

<strong>National</strong> Reference Laboratory (NRL) that is yet to be established.<br />

DA agencies which currently perform st<strong>and</strong>ards development function<br />

should be stripped of this power. All DA regulation <strong>and</strong> enforcement<br />

functions that are currently under BPI, BAI, NMIS, BFAR, FPA, NFA,<br />

PCA, SRA, NTA, <strong>and</strong> CODA should be consolidated under an Inspection<br />

<strong>and</strong> Regulation Service (IRS). The function would include product quality<br />

<strong>and</strong> safety, <strong>and</strong> plant <strong>and</strong> animal health inspection <strong>and</strong> regulation. The<br />

role of the LGUs in enforcement should be clarified to avoid confusion<br />

that leads to conflict as well as gaps.<br />

BAFPS should continue to act as Codex Contact Point (CCP). It should<br />

also be host <strong>and</strong> Secretariat to the <strong>National</strong> Codex Committee (NCC),<br />

the SPS Enquiry <strong>and</strong> Notification Point.<br />

Market development <strong>and</strong> market promotion activities fall under the<br />

purview of <strong>and</strong> should be turned over by the regulatory agencies to<br />

AMAS. For most regulatory agencies, product research <strong>and</strong><br />

development could be performed by government research or academic<br />

institutions. These activities are usually funded with resources from<br />

commodity programs or BAR anyway. They also compete for resources<br />

within the agency.<br />

(d) The fourth amendment is the establishment of a Central Laboratory<br />

Service (CLS) to address the critical issues of the state, utilization,<br />

performance, staffing <strong>and</strong> funding of all laboratories that are so important<br />

to st<strong>and</strong>ards formulation <strong>and</strong> regulation.<br />

(e) For the fifth amendment, the “extended AFMA” funding should make<br />

specific provisions for multi-year funding for infrastructure, facilities <strong>and</strong><br />

equipment; research for st<strong>and</strong>ards setting; <strong>and</strong> research related to<br />

agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries safety issues.<br />

To address the eternal funding constraints, some services could be<br />

shifted to a “user fee” system which simply means user pays for<br />

services, for example, inspection for certification/accreditation/permits,<br />

<strong>and</strong> laboratory services.<br />

The fifth revision should authorize all concerned agencies to retain all<br />

fees collected by the agency to be used to sustain operation instead of<br />

being turned over to the Bureau of Treasury.<br />

xvii

(f) Review of AFMA – Related Laws <strong>and</strong> Current Donor Projects<br />

The review <strong>and</strong> amendment of AFMA is the best time to conduct a<br />

comprehensive review of the Philippine agriculture <strong>and</strong> fishery safety<br />

system, especially if the policy makers choose to adopt an integrated<br />

system to minimize duplication <strong>and</strong> eliminate the gaps <strong>and</strong> enhance<br />

efficiency as recommended in this report.<br />

DA <strong>and</strong> COCAFM should revisit the on-going projects to review the<br />

relevance <strong>and</strong> consistency of the current efforts under those projects<br />

with the Agriculture <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong> Control objectives under the proposed<br />

AFMA amendment. DA should ensure that the projects are aligned with<br />

the objective of strengthening of the agriculture <strong>and</strong> fishery control<br />

system to protect the Filipino consumer as well as consumers of the<br />

Philippine export products equally <strong>and</strong> promotes the competitiveness of<br />

Philippine products in the domestic as well as foreign markets.<br />

8. Research <strong>and</strong> Extension (Sections 80-95)<br />

On research, the following are recommended:<br />

(a) the IRR must be revised <strong>and</strong> that the task of revision must be the<br />

responsibility of BAR <strong>and</strong> ATI.<br />

(b) The utility of a consultative approach is good only if there is a good<br />

recording <strong>and</strong> there is a task force that will integrate the results of the<br />

consultation.<br />

(c) A framework should be developed <strong>and</strong> it is suggested that resource<br />

management is used as a framework.<br />

(d) The consultation is most invaluable in sharpening the edges of an agreed<br />

upon framework.<br />

(e) The pros <strong>and</strong> con of consultation. It could be said that the inherent<br />

difficulties embedded in AFMA’s IRR is its abstract orientation <strong>and</strong> the<br />

difficulty of translating them into action.<br />

(f) Consultation is an interpretive action. However, the issue on how to<br />

integrate such action is not easy to do. This could have been facilitated<br />

<strong>and</strong> made easy if the consultation process was based on an agreed upon<br />

frame of reference. Without this, the present IRR is fragmented <strong>and</strong> it is<br />

very difficult to see how the different components are linked to form a<br />

unity.<br />

(g) The RDE component is a clear illustration of this. Many of the rules are<br />

stated in the abstract. Take the case of research in relation to improving<br />

research structural performance:<br />

Rule 81.2.1 - The term enhance shall denote the improved<br />

responsiveness <strong>and</strong> usefulness of research <strong>and</strong> extension to the<br />

livelihood concerns of agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries operators <strong>and</strong><br />

entrepreneurs.<br />

xviii

The use of the term livelihood is not clear. Generally, this is used to refer<br />

to income generation projects (IGPs). Why not productivity <strong>and</strong><br />

profitability?<br />

Rule 81.2.3 The term consolidate means the unification in strategy,<br />

approach <strong>and</strong> vision, of agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries components of the<br />

ongoing <strong>National</strong> Agriculture Research <strong>and</strong> Extension Agenda (NAREA)<br />

formulated by the Department of Science <strong>and</strong> Technology Agenda for<br />

<strong>National</strong> Development (STAND) formulated by DOST, as well as the<br />

unification of the overall management of, <strong>and</strong> responsibility for, the<br />

research <strong>and</strong> extension system, in agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries under the<br />

Department at the national level <strong>and</strong> under the LGUs at the local level.<br />

The use of the term unification is not clear. In theory, it is from the vision<br />

where the strategies <strong>and</strong> approaches are derived. These can, therefore,<br />

be integrated only on the basis of an agreed upon vision. In other words,<br />

unify the vision to integrate action.<br />

Rule 81.8.1 – (The CERDAF shall) promote the integration of research,<br />

development <strong>and</strong> extension functions <strong>and</strong> enhance the participation of<br />

farmers, fisherfolk, the industry <strong>and</strong> the private sector in the<br />

development of the national research, development <strong>and</strong> extension<br />

agenda.<br />

For a long time now, we have been trying to integrate our development<br />

activities to no avail. It seems that in developing the IRR we have not<br />

brought to bear our major lessons learned in RDE.<br />

Rule 81.8.2 Prepare <strong>and</strong> oversee the implementation of a<br />

comprehensive program RDE to enhance, support, consolidate <strong>and</strong><br />

make full use of the capabilities of the interlinked NaRDSAP<br />

What does comprehensive entail? There are at least two meanings of<br />

the term: 1) comprehensive internally e.g. with commodity; <strong>and</strong>, 2)<br />

between commodities. Does the term refer to both cases? This is not<br />

clear.<br />

Rule 81.9.2 Develop methodologies <strong>and</strong> systems for effective<br />

research, development <strong>and</strong> extension planning in agriculture <strong>and</strong><br />

fisheries emphasizing the quality <strong>and</strong> intensity of participation…<br />

In view of the specific use of the concept methodology in research, the<br />

appropriate term is strategies. Also what is meant by quality <strong>and</strong><br />

intensity?<br />

Rule 81.13.1 Provide national leadership in the planning <strong>and</strong><br />

orchestration of the implementation of M & E of the RDE program.<br />

Again this should be made more explicit since agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries<br />

are multi-commodity systems<br />

xix

Extension<br />

Rule 81.14.1 Provide leadership in the planning <strong>and</strong> orchestration of the<br />

implementation of M & E of an integrated RDE within a farming<br />

systems approach in coordination with the Regional Training Center<br />

(RTC).<br />

Again the term integrated must be spelled out. Why the sudden<br />

appearances of farming systems approach? Is this the key to<br />

modernization or something else? Make this clear <strong>and</strong> show how it fits<br />

the overall RDE system.<br />

The RDE expert considers the section on extension to be weak. The section is<br />

mainly focused on structural arrangement <strong>and</strong> barely on substantive matters.<br />

(a) The link between research <strong>and</strong> extension was hardly discussed.<br />

(b) The precise role of research output in the design of extension service<br />

was not specified.<br />

(c) The basis function of information in extension was not discussed.<br />

(d) The transformative impact of information on agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries was<br />

not discussed in extension work.<br />

(e) The role of IEC in relation to ICT was not included in the design of<br />

extension work. The innovative <strong>and</strong> creative role of SUCs in assisting<br />

LGUs in institutionalization a new mode of production systems through<br />

human resource development was not given much importance.<br />

(f) The expert would like to recommend, therefore, that the section on<br />

research could st<strong>and</strong> as such. What needs to be done is mainly<br />

clarification of definitions <strong>and</strong> putting them in the right context.<br />

(g) It is the section on extension that would require major overhaul.<br />

(h) The substance of extension was not discussed in terms of the<br />

complementation of innovation <strong>and</strong> improvements in information <strong>and</strong><br />

knowledge management.<br />

Its implications to the delivery of extension service <strong>and</strong> to the management of<br />

agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries were not discussed.<br />

9. Institutions <strong>and</strong> Bureaucracy.<br />

The most important task for Congress is to ensure the reorganization of the DA<br />

consistent with the requirements of AFMA <strong>and</strong> the recommendations of the<br />

AGRICOM. This task can be pursued in several ways depending on the position<br />

legislators will take regarding the limits of executive <strong>and</strong> legislative<br />

reorganization.<br />

(a) If Congress takes the position that the power to reorganize fundamentally<br />

or solely resides in the legislature then it must prioritize the following:<br />

• The enactment of a law providing for a system-wide reorganization of<br />

the bureaucracy.<br />

• The enactment of Senate Bill 240 (Osmeña Bill) which provides for the<br />

reorganization of the DA along functional lines as provided for in the<br />

xx

AFMA Report <strong>and</strong> RA 8435. The main provisions of the proposed<br />

rationalization plan under E.O. 366 can be incorporated as author or<br />

committee amendments to SB240.<br />

• Legislative action on bills that reorganize the <strong>National</strong> Food Authority<br />

<strong>and</strong> the creation of a separate Department of Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Aquatic<br />

Resources.<br />

(b) If Congress adheres to the more radical view that the President has<br />

continuing powers to reorganize the bureaucracy as provided for by P.D.<br />

1416, PD 1772 <strong>and</strong> the E.O. 292 then it must:<br />

• Support the on-going reorganization effort undertaken through E.O.<br />

366 <strong>and</strong> impress upon the DA leadership the need for a more radical<br />

reorganization that includes government corporations.<br />

• Request the President to issue an executive order to rationalize the<br />

NFA <strong>and</strong> other commodity corporations consistent with the AFMA<br />

recommendations.<br />

(c) Congress must also exercise its oversight powers, either through the<br />

COCAFM or through independent third-party policy assessment, to<br />

determine:<br />

• Whether the creation of a separate DA-BFAR regional unit <strong>and</strong> the<br />

existence of two separate DA regional offices has actually improved<br />

governance in the fishery sector to determine the appropriate<br />

integration of agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries offices at the regional level.<br />

• The extent of implementation of key tasks given to the BFAR by the<br />

Fisheries Code such as the demarcation of fishing areas; updating of<br />

the Philippine Marine map including the delineation of the boundaries<br />

<strong>and</strong> depth of municipal waters; conduct of an inventory of rare,<br />

threatened <strong>and</strong> endangered aquatic species; providing assistance to<br />

local government units particularly the delineation of the boundaries of<br />

municipal waters, establishment of a comprehensive information<br />

network at the local level for collecting, storage <strong>and</strong> retrieval of fishery<br />

data; <strong>and</strong> the establishment of monitoring, control <strong>and</strong> surveillance<br />

system of Philippine waters at the national <strong>and</strong> local levels.<br />

• The extent <strong>and</strong> quality of participation of agriculture stakeholders in the<br />

boards <strong>and</strong> councils of agricultural agencies to increase participation in<br />

DA governance <strong>and</strong> guide the rationalization of these agencies either<br />

through an executive order or a reorganization law.<br />

• The status of implementation of the provisions of the Fisheries Code<br />

(RA 8550) on the organization of fisheries <strong>and</strong> aquatic resources<br />

management councils <strong>and</strong> integrated fisheries <strong>and</strong> aquatic resources<br />

management councils to guide legislative action on the institutional<br />

arrangements that best promote stakeholders participation in the<br />

development of fisheries <strong>and</strong> aquatic resources.<br />

• The extent of participation of local governments through the leagues or<br />

the Union of Local Authorities of the Philippines (ULAP) in the boards<br />

<strong>and</strong> councils of the various commodity corporations <strong>and</strong> attached<br />

xxi

agencies <strong>and</strong> develop the appropriate mechanisms of participation of<br />

local governments in the governance of these institutions.<br />

• The expenditure pattern of local governments for devolved services in<br />

terms of compliance with the requirements of the Local Government<br />

Code, the level of national government non-IRA funding needed to spur<br />

agricultural modernization, <strong>and</strong> incentives needed to convince local<br />

governments to allocate more resources for agriculture.<br />

• The implementation of E.O. 344 in terms of its policy objective to<br />

determine LGU-compliance with the LGC m<strong>and</strong>ates on the devolution<br />

of agriculture functions, <strong>and</strong> the appropriate DA RFU-LGU linkages that<br />

will help promote agricultural modernization.<br />

10. Human Resource Development (Sections 65-78)<br />

The incomplete implementation of AFMA to establish a <strong>National</strong> Agriculture <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Fishery</strong> Education System was not a case of lack of initiatives among the<br />

agencies involved but simply a typical case of budgetary inadequacy for new <strong>and</strong><br />

incremental initiatives of these agencies using already regularly allocated funds.<br />

In this regard, the following recommendations are suggested:<br />

(a) Strengthen the operational <strong>and</strong> technical working relationships between<br />

the DA, the CHED, DepEd <strong>and</strong> TESDA in focusing prioritized program of<br />

activities in the establishment of quality, efficient, competitive <strong>and</strong><br />

sustainable <strong>National</strong> Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Fisheries Education System<br />

(NAFES) in the country;<br />

(b) The DA should take the lead role in facilitating the immediate transfer of<br />

funds from the budget allocated to AFMA for the NAFES; <strong>and</strong><br />

(c) Revisit more intensively the NAFES Policies, Plan <strong>and</strong> implementing<br />

Guidelines established in 2002 <strong>and</strong> select strategic core HRD activities<br />

that can propel the effective realization of NAFES.<br />

11. Rural Non-Farm Employment (Sections 98-107)<br />

Rural industrialization is a critical element of rural development. The importance<br />

of employment in the non-farm sector can not be over-emphasized. With small<br />

holdings, agriculture alone will be unable to absorb the increase in labor force in<br />

the sector.<br />

(a) The Basic Need Program (BNP) goals must be revisited as they are<br />

ambitious <strong>and</strong> duplicate agency activities.<br />

(b) The BOI incentives for agriculture <strong>and</strong> fisheries appear in order.<br />

However, investments in ecozones for exports should also be promoted;<br />

<strong>and</strong><br />

(c) The training <strong>and</strong> certification of workers should continue but it must be<br />

market <strong>and</strong> employer-driven.<br />

CONCLUSIONS<br />

xxii

AFMA is a good law with rather ambitious goals but with lack of political<br />

commitment to fund it. The AFMA elicited a lot of expectations with the additional<br />

resources. There was, however, a weak IEC that did not indicate that all related<br />

programs will form part of the Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Fisheries Modernization Plan. As<br />

a result, the stakeholders felt that implementation was below par, <strong>and</strong> its impact<br />

poor to moderate. There are at least several footnotes to the review:<br />

1. The budget by components (in percentage terms) was not followed;<br />

2. There was bias for production-support, <strong>and</strong> less in marketing, R & D,<br />

human resources development <strong>and</strong> inter-agency linkages;<br />

3. There was little concern for regional priorities;<br />

4. The need for sound criteria for project selection was not explicit;<br />

5. The role of private investments in growth <strong>and</strong> job creation was not explicit;<br />

<strong>and</strong><br />

6. PBME was severely inadequate which, in part, affected the effectiveness<br />

of the Review Team.<br />

Looking forward, the amendments to AFMA <strong>and</strong> its IRR will be big steps forward.<br />

However, they are insufficient conditions unless funds are forthcoming <strong>and</strong> they<br />

are allocated with sound criteria. Lastly, there are important aspects of the<br />

enabling environment that are not part of the AFMA Review but they are also<br />

necessary elements to move a competitive agriculture, fishery <strong>and</strong> agri-industry<br />

to full speed. These include:<br />

1. Amendments to the CARP Law (e.g. free the l<strong>and</strong> markets to bring<br />

collateral value to agricultural l<strong>and</strong>s);<br />

2. Amendments to the Local Government Code (e.g. to revisit the disjointed<br />

lines of authority between the provincial agriculture officers <strong>and</strong> the<br />

municipal agriculture officers);<br />

3. Review of the Fisheries Code as it relates to the AFMA;<br />

4. Implementation of existing laws (e.g. Tarrification Law);<br />

5. A meritocratic bureaucracy;<br />

6. Continuity in leadership, particularly in the DA; <strong>and</strong><br />

7. Good local governance (e.g. sound use of IRA for agriculture<br />

development).<br />

These will bring agriculture, fisheries <strong>and</strong> agri-industry growth to full speed, <strong>and</strong>,<br />

in turn, reduce rural poverty.<br />

xxiii

Chapter Summaries<br />

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION<br />

1. The Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Fisheries Modernization Act (AFMA) became a law in<br />

late 1997. The Implementing Rules <strong>and</strong> Regulations (IRR) was issued in<br />

July 1998. From budget resource st<strong>and</strong>point, full implementation started in<br />

1999. The AFMA expired in 2004 but was quickly extended by Congress<br />

to 2015 in March 2005.<br />

2. The AFMA Review is anchored on Section 117 which provides:<br />

• Section 117. Automatic Review – Every five years after the effectivity of the<br />

Act, an independent panel composed of experts to be appointed by the<br />

President shall review the polices <strong>and</strong> programs in the Agriculture <strong>and</strong><br />

Fisheries Modernization Act <strong>and</strong> shall make recommendations based on its<br />

findings, to the President <strong>and</strong> to both Houses of Congress.<br />

3. The IRR Rule 117.1 further provides that:<br />

• The services of an independent review panel shall be recommended to the<br />

President by the COCAFM, <strong>and</strong> upon the President’s approval, be engaged<br />

by the COCAFM Secretariat no later than the end of the third year after the<br />

effectivity of the Act, to allow for adequate preparation for the automatic<br />

review.<br />

4. In July 2005, the Congressional Oversight Committee on <strong>Agricultural</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

Fisheries Modernization (COCAFM) <strong>and</strong> the CRC Foundation signed the<br />

Memor<strong>and</strong>um of Agreement witnessed by the representatives of the<br />

<strong>National</strong> <strong>Agricultural</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fishery</strong> <strong>Council</strong> (NAFC) <strong>and</strong> Strive Foundation.<br />

5. This draft final report is among the several milestones ending with the final<br />

report after comments from COCAFM, DA, <strong>and</strong> NAFC have been<br />

incorporated. This report contains heavy inputs from the stakeholders<br />

following the regional consultations <strong>and</strong> surveys of leading producer<br />

associations.<br />

6. The AFMA Review Study is expected to: (a) evaluate <strong>and</strong> measure the<br />

impact of AFMA <strong>and</strong> its programs on outputs; (b) to analyze the flow of<br />

budgetary resources to the sector <strong>and</strong> specific industries (if possible); (c)<br />

determine how AFMA was implemented through specific sector <strong>and</strong><br />

commodity-specific studies, surveys <strong>and</strong> consultation workshops; <strong>and</strong> (d)<br />

recommend policy directions, program interventions, <strong>and</strong> amendments to<br />

the law <strong>and</strong> IRR (Ref: Inception Report, August 1, 2005).<br />

7. The Report will have the following coverage:<br />

a. Analysis of agriculture performance, pre-AFMA <strong>and</strong> post-AFMA;<br />

b. Reports by AFMA components with recommendations; <strong>and</strong><br />

xxiv

c. Commodity specific reports<br />

CHAPTER 2. METHODOLOGY<br />

8. Since AFMA visualizes as a strategy the transformation of Philippine<br />

agriculture from a resource-based to technology <strong>and</strong> market-driven<br />

agriculture, the team of consultants will assess as an entry point, the<br />

development of the Strategic Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Fisheries Development Zone<br />

(SAFDZ) as the convergence for AFMA related development interventions<br />

evolving into integrated development plans that will serve as inputs to the<br />

<strong>National</strong> Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Fisheries Modernization Plan.<br />

9. The project team used both primary <strong>and</strong> secondary data. Primary data<br />

were gathered through interviews with key informants from the<br />

government <strong>and</strong> the private sector. A series of regional consultations<br />

were also conducted before report finalization. Meanwhile, secondary<br />

data were collected from government agencies, data banks of international<br />

organizations, research firms, <strong>and</strong> private institutions.<br />

10. The analysis covered nine plus two additional components of AFMA as<br />

follows: (a) marketing <strong>and</strong> information; (b) trade <strong>and</strong> fiscal incentives; (c)<br />

irrigation; (d) credit; (e) other infrastructure <strong>and</strong> post-harvest facilities; (f)<br />

budget/finance; (g) product st<strong>and</strong>ardization <strong>and</strong> consumer safety; (h)<br />

research, development <strong>and</strong> extension; <strong>and</strong> (i) institutions <strong>and</strong> bureaucracy.<br />

The two other components which were not included in the original<br />

mainstream terms of reference of the Team of Experts were: (j) human<br />

resource development; <strong>and</strong> (k) rural non-farm employment. Their<br />

analysis, however, was not as extensive as the other nine due to<br />

budgetary constraints.<br />

11. The chapter assessed the different AFMA components <strong>and</strong> activities <strong>and</strong><br />

discussed how these translated into the performance of agriculture <strong>and</strong><br />

fisheries. It also analyzed the flow of budgetary resources to the<br />

agriculture <strong>and</strong> fishery sectors as well as its effects on employment <strong>and</strong><br />

poverty alleviation. Given the review <strong>and</strong> analysis undertaken, the study<br />

proposed policy <strong>and</strong> program recommendations that can enhance the<br />

effective implementation of AFMA.<br />

CHAPTER 3. AGRICULTURE PERFORMANCE<br />