- Page 1 and 2:

April 2009 Volume 12 Number 2

- Page 3 and 4:

Abstracting and Indexing Educationa

- Page 5 and 6:

Engaging students in multimedia-med

- Page 7 and 8:

this study discusses computer-based

- Page 9 and 10:

Sampling for preliminary study One

- Page 11 and 12:

Part 2 Pearson correlation .349** 1

- Page 13 and 14:

Figure 1. Box and whisker plot of t

- Page 15 and 16:

characteristics and learning styles

- Page 17 and 18:

However, critical reflection and in

- Page 19 and 20:

novels, so they collected any relat

- Page 21 and 22:

1. Theories of teaching: Comments m

- Page 23 and 24: grammatical errors and basic writin

- Page 25 and 26: Ho, B., & Richards, J. C. (1993). R

- Page 27 and 28: Hwang, K.-A., & Yang, C.-H. (2009).

- Page 29 and 30: e deduced from the Affective Domain

- Page 31 and 32: Detection procedure Figure 1 shows

- Page 33 and 34: avoided. Image processing is perfor

- Page 35 and 36: falling asleep) as defined in this

- Page 37 and 38: classmates or left their seats duri

- Page 39 and 40: help teachers to recognize the lear

- Page 41 and 42: Hsieh, P.-H., & Dwyer, F. (2009). T

- Page 43 and 44: significant comprehension effects o

- Page 45 and 46: Treatment 3 (keyword group): Studen

- Page 47 and 48: Criteria of achievement measures Th

- Page 49 and 50: esults. A correlational analysis de

- Page 51 and 52: A 2 x 1 ANOVA analyzed the effect o

- Page 53 and 54: References Aragon, S. R. (2004). In

- Page 55 and 56: Raphael, T. (1982). Improving quest

- Page 57 and 58: educing maintenance costs. The cont

- Page 59 and 60: Synchronization functions According

- Page 61 and 62: inconsistency) and navigate directl

- Page 63 and 64: the suitability of the instructiona

- Page 65 and 66: Design of manipulation process The

- Page 67 and 68: Table 1: Comparative analysis of au

- Page 69 and 70: the convenience of mobile-based ass

- Page 71 and 72: According to evaluation result, the

- Page 73: Tan, O. S., Parsons, R. D., Hinson,

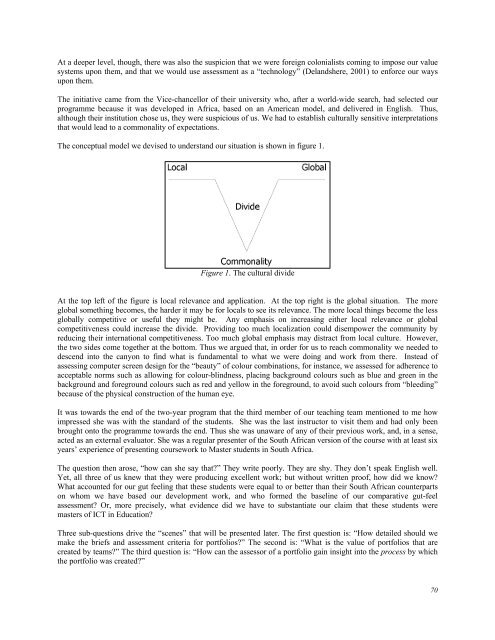

- Page 77 and 78: theoretical assumptions. Two theore

- Page 79 and 80: The students were not going to have

- Page 81 and 82: slightly different. The group who c

- Page 83 and 84: every item, not giving any result.

- Page 85 and 86: edited and presented to the class u

- Page 87 and 88: Figure 10. Screen captures from the

- Page 89 and 90: Some of the concerns that emerge fr

- Page 91 and 92: Ajayi, L. (2009). An Exploration of

- Page 93 and 94: As a result of the confluence of di

- Page 95 and 96: peers (Schellens et al. 2005). Sche

- Page 97 and 98: The integration of discussion board

- Page 99 and 100: ecause the technology allowed the p

- Page 101 and 102: The pre-service teachers perceived

- Page 103 and 104: Furthermore, the study demonstrated

- Page 105 and 106: Schellens, T., van Keer, H., & Valc

- Page 107 and 108: McKean, 2003). Instructors will see

- Page 109 and 110: program at The Ohio State Universit

- Page 111 and 112: Knowledge and skills of developing

- Page 113 and 114: their monthly reflections or assign

- Page 115 and 116: Bull, K., Montgomery, D., Overton,

- Page 117 and 118: frustrating the student). ITSs make

- Page 119 and 120: • Link removal - advanced student

- Page 121 and 122: Expert Module Expert Module’s mai

- Page 123 and 124: Based on the questionnaire results

- Page 125 and 126:

students were told that their perfo

- Page 127 and 128:

thirds of the interviewed students

- Page 129 and 130:

Throughout the semester, students i

- Page 131 and 132:

human teacher or question developer

- Page 133 and 134:

To test the learning effectiveness

- Page 135 and 136:

APPENDIX A Computer Science and Sof

- Page 137 and 138:

Thus, the use of computers changes

- Page 139 and 140:

Specifically, two objectives were p

- Page 141 and 142:

Nonetheless, both teachers assign a

- Page 143 and 144:

48% 35% 53% similar similar 69% 42%

- Page 145 and 146:

Table 4: Students’ attitudes Stat

- Page 147 and 148:

activities. Specifically, the histo

- Page 149 and 150:

Huang, Y.-M., Huang, T.-C., Wang, K

- Page 151 and 152:

• Could recommended learning sequ

- Page 153 and 154:

Analysis of sequences prediction me

- Page 155 and 156:

Figure 4. The sorting of learning s

- Page 157 and 158:

The figures 5a and 5b illustrate th

- Page 159 and 160:

Learning sequence recommendation sy

- Page 161 and 162:

In this study, forty subjects were

- Page 163 and 164:

The potential for LSRS to promote l

- Page 165 and 166:

They pointed out that LSRS helped t

- Page 167 and 168:

Cover, T. M., & Thomas, J. A. (1991

- Page 169 and 170:

Related Efforts An Internet forum i

- Page 171 and 172:

with handheld devices and they were

- Page 173 and 174:

agent would direct learners to a le

- Page 175 and 176:

Mobile RSS Aggregator In order to s

- Page 177 and 178:

learning, such as posting question

- Page 179 and 180:

With novel technological support, m

- Page 181 and 182:

Shen, L., Wang, M., & Shen, R. (200

- Page 183 and 184:

as an ‘affective loop’, which r

- Page 185 and 186:

Figure 2 is an example of two-dimen

- Page 187 and 188:

preference was gathered through dat

- Page 189 and 190:

compute the heart rate (HR) as a fu

- Page 191 and 192:

sessions. Of all the 18 learning se

- Page 193 and 194:

Burleson, W., Picard, R. W., Perlin

- Page 195 and 196:

Wu, C.-C., & Lai, C.Y. (2009). Wire

- Page 197 and 198:

The wireless handheld learning envi

- Page 199 and 200:

the lengthiness of the scales, whic

- Page 201 and 202:

Nursing dictionary We constructed a

- Page 203 and 204:

them. The computers were networked

- Page 205 and 206:

“The major difference was that I

- Page 207 and 208:

questionnaire. We do not consider t

- Page 209 and 210:

Faruque, F., Hewlett, P. O., Wyatt,

- Page 211 and 212:

etween a user and the system. Addit

- Page 213 and 214:

Figure 2. A concept map representin

- Page 215 and 216:

C5.0 can help teachers to generate

- Page 217 and 218:

that a selected programming exercis

- Page 219 and 220:

differences between our system and

- Page 221 and 222:

1(students can complete without any

- Page 223 and 224:

The PADS sometimes assigned very di

- Page 225 and 226:

Corno, L. (2000). Looking at Homewo

- Page 227 and 228:

Hwang, W.-Y., Hsu, J.-L., Tretiakov

- Page 229 and 230:

listed these functions as allowing

- Page 231 and 232:

In the research presented in this a

- Page 233 and 234:

Research Tools Web-based learning e

- Page 235 and 236:

Table 1. Operational definitions of

- Page 237 and 238:

action, interaction, and outeractio

- Page 239 and 240:

for them was getting the answer as

- Page 241 and 242:

Table 6 shows the learners’ prefe

- Page 243 and 244:

Bell, P., & Winn, W. (2000). Distri

- Page 245 and 246:

Askar, P., & Altun, A. (2009). CogS

- Page 247 and 248:

elations, interactions and activiti

- Page 249 and 250:

Figure 3. A comparison of knowledge

- Page 251 and 252:

ontology will easily be extensible

- Page 253 and 254:

Figure 7. Visual Representation of

- Page 255 and 256:

Step 5: Use Boolean to combine the

- Page 257 and 258:

2) CogSkillNet provides classroom i

- Page 259 and 260:

Neo, M., & Neo, T.-K. (2009). Engag

- Page 261 and 262:

• Conversation and collaboration

- Page 263 and 264:

IMAGE 2 2. Problem identification I

- Page 265 and 266:

Methodology At the end of the proje

- Page 267 and 268:

presentation skills (m = 3.72), and

- Page 269 and 270:

6. Can’t be denying that, sometim

- Page 271 and 272:

Lambert, N. M., & McCombs, B. J. (1

- Page 273 and 274:

not detected in a previous study, t

- Page 275 and 276:

et al. (2001) studied the learning

- Page 277 and 278:

all the students. At the midpoint o

- Page 279 and 280:

The observed pairs were aware of be

- Page 281 and 282:

Table 2 shows the results from a mo

- Page 283 and 284:

Table 5: The distribution of time (

- Page 285 and 286:

As discussed in the section on prev

- Page 287 and 288:

McDowell, C., Werner, L., Bullock,

- Page 289 and 290:

Comprehension monitoring is the awa

- Page 291 and 292:

or roles in a context, such as “I

- Page 293 and 294:

Correlation coefficient was also co

- Page 295 and 296:

(a) Text 1 (b) Text 2 (c) Text 3 (d

- Page 297 and 298:

Table 3 shows that the average read

- Page 299 and 300:

Figure 10. Trace results of the les

- Page 301 and 302:

monitor their reading process and h

- Page 303 and 304:

Conn, S. R., Roberts, R. L., & Powe

- Page 305 and 306:

The technology-mediated groups, wit

- Page 307 and 308:

hybrid model of supervision was pos

- Page 309 and 310:

Our research indicates that the hyb

- Page 311 and 312:

Janoff, D. S., & Schoenholtz-Read,

- Page 313 and 314:

goal of using storyboards. But, thi

- Page 315 and 316:

In general, learning activities nee

- Page 317 and 318:

Furthermore, free subjects, such as

- Page 319 and 320:

Storyboarding Roots and related wor

- Page 321 and 322:

Referees, on the other hand, may wa

- Page 323 and 324:

Symbols Interpretation Defines a un

- Page 325 and 326:

Figure 4. Top-level storyboard for

- Page 327 and 328:

may take subjects such as practical

- Page 329 and 330:

network security information envir

- Page 331 and 332:

The concrete procedure and interact

- Page 333 and 334:

(e.g., for graduation) using such i

- Page 335 and 336:

Thus, academic education modeling b

- Page 337 and 338:

Feyer, T., Kao, O., Schewe, K.-D.,

- Page 339 and 340:

Richards, G. (2009). Book review: T

- Page 341 and 342:

expands the child’s proximal envi

- Page 343:

Chapter 6 exemplifies the activitie