South African Choral Music (Amakwaya): Song, Contest and the ...

South African Choral Music (Amakwaya): Song, Contest and the ...

South African Choral Music (Amakwaya): Song, Contest and the ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

354 Westem Repertoire<br />

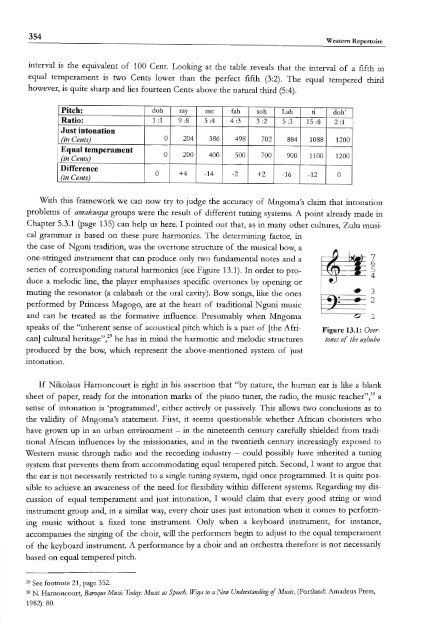

interval is <strong>the</strong> equivalent of 100 Cent. Looking at <strong>the</strong> table reveals that <strong>the</strong> interval of a fifth in<br />

equal temperament is two Cents lower than <strong>the</strong> perfect fifth (3:2). The equal tempered third<br />

however, is quite sharp <strong>and</strong> lies fourteen Cents above <strong>the</strong> natural third (5:4).<br />

Pitch: doh ray me fah soh Lah ti doh'<br />

Ratio: 1 :1 9:8 5 :4 4:3 3 :2 5:3 15:8 2 :1<br />

Just intonation<br />

(in Cents) 0 204 386 498 702 884 1088 1200<br />

Equal temperament<br />

(in Cents)<br />

0 200 400 500 700 900 1100 1200<br />

Difference<br />

(in Cents)<br />

0 +4 -14 -2 +2 -16 -12 0<br />

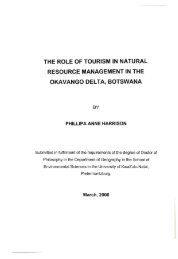

With this framework we can now try to judge <strong>the</strong> accuracy of 1\tIngoma's claim that intonation<br />

problems of amakwCfYa groups were <strong>the</strong> result of different tuning systems. A point already made in<br />

Chapter 5.3.1 (page 135) can help us here. I pointed out that, as in many o<strong>the</strong>r cultures, Zulu musical<br />

grammar is based on <strong>the</strong>se pure harmonics. The determining factor, in<br />

<strong>the</strong> case of Nguni tradition, was <strong>the</strong> overtone structure of <strong>the</strong> musical bow, a<br />

one-stringed instrument that can produce only two fundamental notes <strong>and</strong> a<br />

series of corresponding natural harmonics (see Figure 13.1). In order to produce<br />

a melodic line, <strong>the</strong> player emphasises specific overtones by opening or<br />

muting <strong>the</strong> resonator (a calabash or <strong>the</strong> oral cavity). Bow songs, like <strong>the</strong> ones<br />

performed by Princess Magogo, are at <strong>the</strong> heart of traditional Nguni music<br />

<strong>and</strong> can be treated as <strong>the</strong> formative influence. Presumably when Mngoma<br />

speaks of <strong>the</strong> "inherent sense of acoustical pitch which is a part of [<strong>the</strong> <strong>African</strong>]<br />

cultural heritage",29 he has in mind <strong>the</strong> harmonic <strong>and</strong> melodic structures<br />

produced by <strong>the</strong> bow, which represent <strong>the</strong> above-mentioned system of just<br />

intonation.<br />

7 654<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

Figure 13.1: Overtones<br />

of <strong>the</strong> uJ!hubo<br />

If Nikolaus Harnoncourt is right in his assertion that "by nature, <strong>the</strong> human ear is like a blank<br />

sheet of paper, ready for <strong>the</strong> intonation marks of <strong>the</strong> piano tuner, <strong>the</strong> radio, <strong>the</strong> music teacher",3° a<br />

sense of intonation is 'programmed', ei<strong>the</strong>r actively or passively. This allows two conclusions as to<br />

<strong>the</strong> validity of Mngoma's statement. First, it seems questionable whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>African</strong> choristers who<br />

have grown up in an urban environment - in <strong>the</strong> nineteenth century carefully shielded from traditional<br />

<strong>African</strong> influences by <strong>the</strong> missionaries, <strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong> twentieth century increasingly exposed to<br />

Western music through radio <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> recording industry - could possibly have inherited a tuning<br />

system that prevents <strong>the</strong>m from accommodating equal tempered pitch. Second, I want to argue that<br />

<strong>the</strong> ear is not necessarily restricted to a single tuning system, rigid once programmed. It is quite possible<br />

to achieve an awareness of <strong>the</strong> need for flexibility within different systems. Regarding my dis<br />

cussion of equal temperament <strong>and</strong> just intonation, I would claim that every good string or wind<br />

instrument group <strong>and</strong>, in a similar way, every choir uses just intonation when it comes to performing<br />

music without a fixed tone instrument. Only when a keyboard instrument, for instance,<br />

accompanies <strong>the</strong> singing of <strong>the</strong> choir, will <strong>the</strong> performers begin to adjust to <strong>the</strong> equal temperament<br />

of <strong>the</strong> keyboard instrument. A performance by a choir <strong>and</strong> an orchestra <strong>the</strong>refore is not necessarily<br />

based on equal tempered pitch.<br />

29 See footnote 21, page 352.<br />

30 N. Harnoncourt, Baroque <strong>Music</strong> Todqy: <strong>Music</strong> as Speech. Wqys to a New Underst<strong>and</strong>ing of <strong>Music</strong>, (portl<strong>and</strong>: Amadeus Press,<br />

1982): 80.