Long-term Memory

Long-term Memory

Long-term Memory

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

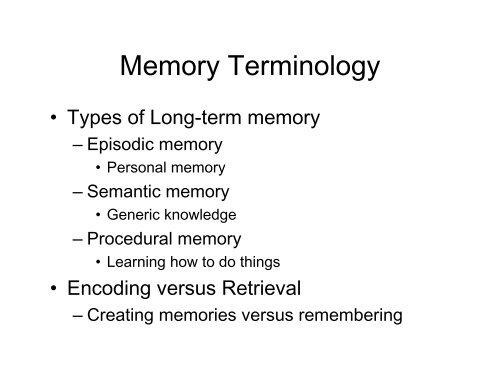

<strong>Memory</strong> Terminology<br />

• Types of <strong>Long</strong>-<strong>term</strong> memory<br />

– Episodic memory<br />

• Personal memory<br />

– Semantic memory<br />

• Generic knowledge<br />

– Procedural memory<br />

• Learning how to do things<br />

• Encoding versus Retrieval<br />

– Creating memories versus remembering

• Modal view of memory (qualitative differences<br />

between STM and LTM)<br />

– Capacity<br />

• STM around 7 chunks, LTM nearly unlimited<br />

– Duration<br />

• STM around 30 seconds, LTM can last a lifetime<br />

– Bahrick (1984) memory for Spanish class declined during first 6<br />

years, but there was no further forgetting even out to 35 years<br />

– Coding<br />

• STM is acoustic<br />

– confuse “b” and “g”<br />

• LTM is semantic<br />

– Baddeley (1966a) – 20 minutes after studying a list<br />

» poor recall for semantically similar lists (HUGE, BIG, SIZE,<br />

etc.)<br />

» normal recall from acoustically similar lists (MAD, MAP,<br />

MAN, etc.)

A Unitary Account of <strong>Memory</strong><br />

• levels of processing: the only difference between STM<br />

and LTM is whether encoding is “shallow” or “deep”<br />

– memory is a continuum, rather than different modes<br />

– deep processing is more semantic and self-referential and<br />

results in stronger, longer lasting memories<br />

• Semantic memories are more distinctive (unique)<br />

• Semantic memories involve elaboration (interconnected)<br />

– shallow processing is concerned with physical characteristics<br />

and results in weaker, temporary memories<br />

– Craik and Tulving (1975) had participants study words with the<br />

following tasks (listed from worst to best memory)<br />

• Is it in upper case?<br />

• Does it rhyme with ?<br />

• Does it fit in the sentence ?

<strong>Long</strong>-<strong>term</strong> <strong>Memory</strong><br />

• Tests of long-<strong>term</strong> memory<br />

– recognition<br />

• how to measure performance?<br />

– increased “hits” (saying old to targets) could be a bias to<br />

always say old<br />

– compare the hit rate to the false alarm rate (saying old to<br />

distractors / foils / lures)<br />

» If familiarity is compared to a criterion, bias and memory<br />

can be separated<br />

– free recall<br />

– cued-recall (paired associate learning)<br />

• study FLAG-SPOON, DRAWER-SWITCH, etc.<br />

• FLAG-______<br />

– results are similar to free recall

Results<br />

• Forgetting Curves<br />

– Ebbinghaus’s (1885) nonsense syllable experiment<br />

• over the course of days, he kept on relearning lists of nonsense<br />

syllables (e.g., RUR, HAL, BEIS, etc.)<br />

• forgetting was measured as percent savings (a comparison of<br />

immediate testing versus testing after a delay)<br />

• information is rapidly forgotten at first (non-linear)

Results cont.<br />

• recall is better when context is kept the same<br />

– encoding specificity<br />

• Thomson and Tulving (1970) – word context<br />

– e.g., studied ‘ground-COLD’<br />

» better recall with ‘ground-?’ than ‘hot-?’<br />

• Golden and Baddeley (1975) – environmental context<br />

– words learned on land or underwater<br />

– words tested on land or underwater<br />

memory<br />

performance<br />

study<br />

on land<br />

study<br />

underwater<br />

test<br />

underwater<br />

test<br />

on land

– encoding specificity cont.<br />

• Marian and Fausey (2006) – language context<br />

• Bransford et al. (1979) – processing context<br />

– Rhyme encoding produces best performance if rhyming<br />

is also used at test (deep processing isn’t always best)

– encoding specificity cont.<br />

• state-dependent learning – a match between<br />

pharmacological states improves memory (Eich, 1980)<br />

memory<br />

performance<br />

study<br />

drunk<br />

study<br />

sober<br />

test<br />

sober<br />

test<br />

drunk<br />

• mood congruence – a match between moods states<br />

affects memory (Murray et al., 1999)<br />

– Depressed people recalled less than nondepressed people<br />

– Nondepressed people recalled many more positive words<br />

than negative words<br />

– Depressed people recalled slightly more negative words<br />

than positive words

Results cont.<br />

• memory is worse when semantically similar<br />

items are studied<br />

– A,B,C, vs. A,A’,A’’ (false memory effect)<br />

• memory for any particular item is worse when<br />

more items are studied<br />

– A,B,C vs. A,B,C,D,E,F (length effect)<br />

• memory is better when each item is studied for a<br />

longer period of time<br />

– A,B,C vs. A,A,A,B,B,B,C,C,C (strength effect)<br />

– however, distributed study is better than massed<br />

study<br />

• spacing effect<br />

– A,A,A,B,B,B,C,C,C vs. C,A,B,A,B,C,B,A,C<br />

– Encoding variability

edspread<br />

betrayal<br />

donate<br />

escapade<br />

holly<br />

iceberg<br />

missile<br />

numeral<br />

outcast<br />

painless<br />

plumber<br />

plural<br />

priority<br />

rancher<br />

reversal<br />

skeleton<br />

trigger<br />

trinket<br />

waffle

Amnesia

• Bilateral damage to the medial temporal lobes (including<br />

the hippocampus)<br />

– inability to make new memories<br />

• anterograde amnesia<br />

– some loss of old memories from just before the damage<br />

• retrograde amnesia<br />

– sources of damage<br />

• permanent: Surgery, stroke, hypoxia, head injury, encephalitis<br />

• progressive: Korsakoff’s syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease<br />

• temporary: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), benzodiazepines<br />

• unilateral hippocampal damage<br />

– left = verbal memory<br />

– right = spatial memory<br />

• hippocampal versus parahippocampal damage<br />

– recall versus familiarity?<br />

brain<br />

damage<br />

PAST PRESENT<br />

retrograde<br />

anterograde

• Anterograde amnesia<br />

– Inability to form new long-<strong>term</strong> episodic<br />

memories<br />

• general knowledge and personal history are frozen<br />

– poor at recall, recognition, etc.<br />

– no new vocabulary (e.g. jacuzzi, granola, etc.)<br />

• intact STM / working memory<br />

• all modalities affected<br />

• Skill learning<br />

– Implicit learning, but no explicit memory (dissociation)<br />

» procedural versus declarative<br />

– motoric or perceptual (i.e., cannot learn chess)<br />

» rotary pursuit<br />

» mirror tracing<br />

» mirror image reading<br />

» new words (not meaning)<br />

» long-<strong>term</strong> priming (stem and fragment completion)

ed__<br />

bet__<br />

don__<br />

esc___<br />

hol___<br />

ice___<br />

miss___<br />

num___<br />

out___<br />

pain___<br />

pl_m__r<br />

p_ur_l<br />

pr_o_ity<br />

ra_c_er<br />

re_e_sal<br />

s_el_ton<br />

t_ig_er<br />

t_in_et<br />

w_f_le

• Retrograde amnesia<br />

– loss of old memories<br />

• some retrograde amnesia with hippocampal damage<br />

– the period just before the injury is forgotten (temporally graded)<br />

– memory consolidation (Squire)<br />

• Memories are dependent on the hippocampus for awhile<br />

– with time, the cortex can learn the memories<br />

– this process is called memory consolidation

Narrative and Autobiographical <strong>Memory</strong><br />

• Do laboratory studies apply to real life memories?<br />

– Bartlett (1932) thought narrative memory is often<br />

reconstructed based on schemas<br />

• Schema: general knowledge or expectation distilled from past<br />

experiences (i.e., the ‘gist’ of things)<br />

– e.g., the ‘eating lunch’ schema<br />

• constructivist view of LTM<br />

• serial reproduction: repeated recall the same story<br />

– Native American story, “War of the Ghosts”, became more distorted<br />

and westernized with each reproduction<br />

– Consistency bias<br />

• Memories are made to be consistent with current self-schema<br />

– Source monitoring errors<br />

• Attributing a memory from source A to source B<br />

– Reality monitoring errors<br />

• Thinking something happened that was just imagined or<br />

planed

– Autobiographical memory for ordinary events<br />

• Marjorie Linton (1975, 1982) spent six years recording the daily<br />

events in her life (2 per day) in a systematic fashion<br />

• each day short descriptions of important events<br />

– the date, how distinctive, how emotional, importance to life goals<br />

• tested herself at delays up to three years<br />

– order two events (which happened first)<br />

– provide exact dates of events<br />

• performance was good at all delays<br />

– real life memories are more durable than what Ebbinghaus found<br />

– she often used problem solving to arrive at the dates of events<br />

» constructivist view of memory<br />

• events that she could not recall where often similar to other events<br />

she could not recall<br />

– repeated similar events can start to form a schema

Flashbulb Memories<br />

(Brown & Kulik, 1977)<br />

• personal events at time of disaster<br />

– JFK assassination, Challenger explosion, start of gulf war, 9/11<br />

• physiological response<br />

– emotional response causes hormone release<br />

• better encoding<br />

• However, positive events better remembered than negative (see pp.<br />

137-140)<br />

– Students in NYC recalled more facts than students in California<br />

• stronger emotional responses = more details

• Weaver (1993) compared intentional memory to<br />

flashbulb memory<br />

– remember next meeting with roommate<br />

• Tested immediately, 3 months, 1 year<br />

– gulf war started at same time (direct comparison)<br />

• No accuracy differences<br />

• Higher confidence for flashbulb<br />

• Talarico & Rubin (2003) compared forgetting of flashbulb<br />

memory to ordinary event

Own Race Bias (ORB)<br />

• People are best at remembering and perceiving<br />

faces of their own race<br />

– Contact hypothesis (Walker & Hewstone, 2006)

ORB and Cue Utilization<br />

• Different races make different eye cosmetic<br />

alterations<br />

– Caucasians: 85% of people who wear soft contact<br />

lenses wear colored lenses (Contact Lens Council, 2000)<br />

– Asians: 39% of plastic surgeries are blepharoplasties, or<br />

double eyelid surgeries (AAFPRS, 2007)

proportion of<br />

descriptions<br />

0.6<br />

0.5<br />

0.4<br />

0.3<br />

0.2<br />

0.1<br />

0<br />

Descriptors Used<br />

Iris Color Eyelid Crease<br />

Asian test face Caucasian test face<br />

Asian Caucasian<br />

Participant race<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

Asian Caucasian<br />

Participant race

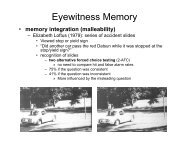

Eyewitness <strong>Memory</strong><br />

• memory integration (malleability)<br />

– Elizabeth Loftus (1978): series of accident slides<br />

• Viewed stop or yield sign<br />

• “Did another car pass the red Datsun while it was stopped at the<br />

stop/yield sign?”<br />

• recognition of slides<br />

– two alternative forced choice testing (2-AFC)<br />

» no need to compare hit and false alarm rates<br />

» Post-event misinformation effect (retroactive interference)

Eyewitness Lineups<br />

• what’s the best way to conduct a lineup?<br />

– maximize identification of guilty suspects (hits)<br />

– minimize identification of innocent suspects (false alarms)<br />

• selecting distractors in a lineup (known-innocents)<br />

– the use of mock eyewitnesses<br />

– match-to-description, or also resemble-suspect?<br />

• either way, innocent suspect is protected<br />

• if distractors resemble-suspect, identification of guilty suspect is lower<br />

• demand characteristics<br />

– subtle cues<br />

– exert pressure to select (relative judgment)<br />

– double-blind eliminates these concerns<br />

• Not adopted by law enforcement<br />

• relative judgments versus absolute identification<br />

– sequential lineups emphasize absolute identification<br />

• reduces identification of innocent suspects<br />

• however, also reduces identification of guilty suspect<br />

• w/o double-blind, can increase demand characteristics

False <strong>Memory</strong> Effect<br />

• Deese (1959) and Roediger<br />

and McDermott (1995) (DRM)<br />

– False recall of critical lure*<br />

– False alarm rate for critical lures*<br />

as high as hit rate<br />

• Explained by summed similarity to<br />

all memories (Shiffrin, Huber, &<br />

Marinelli, 1995)<br />

Test List<br />

Patient<br />

*Doctor<br />

Rest<br />

*Sleep<br />

Nurse<br />

Sick<br />

Medicine<br />

Health<br />

Hospital<br />

Dentist<br />

Physician<br />

cure<br />

Patient<br />

Office<br />

Study Lists<br />

Surgeon<br />

Bed<br />

Rest<br />

Awake<br />

Tired<br />

Dream<br />

Snooze<br />

Blanket<br />

Doze<br />

Snore<br />

Nap<br />

Yawn

Recovered Memories<br />

• Therapy and police interrogation can result in<br />

recovered memories. Are these real?<br />

– Practices that might cause false memories<br />

• Hypnosis<br />

• Imagination exercises<br />

• Leading questions<br />

– Memories can be implanted<br />

• Loftus and Pickrell (1995): 3 true events and one false<br />

“lost-in-the-mall”<br />

– Booklets describing stories (4-6 years) were created by<br />

interviewing relatives<br />

– Participants asked to fill in additional details<br />

– 68% of true stories and 29% of false stories ‘remembered’

• Hyman, Husband, and Billings (1995)<br />

– embarassing stories (e.g., spilling punch bowl at a wedding)<br />

» 80-90% of true events<br />

» no false events recalled in first interview<br />

» 20% in a second interview<br />

» some participants elaborated upon their false memories<br />

(added details never presented)