THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXECUTIVE FUNCTION IN EARLY ...

THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXECUTIVE FUNCTION IN EARLY ...

THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXECUTIVE FUNCTION IN EARLY ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Discussion<br />

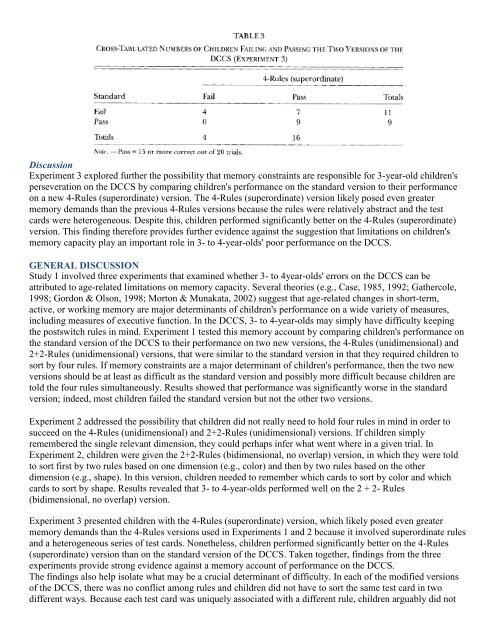

Experiment 3 explored further the possibility that memory constraints are responsible for 3-year-old children's<br />

perseveration on the DCCS by comparing children's performance on the standard version to their performance<br />

on a new 4-Rules (superordinate) version. The 4-Rules (superordinate) version likely posed even greater<br />

memory demands than the previous 4-Rules versions because the rules were relatively abstract and the test<br />

cards were heterogeneous. Despite this, children performed significantly better on the 4-Rules (superordinate)<br />

version. This finding therefore provides further evidence against the suggestion that limitations on children's<br />

memory capacity play an important role in 3- to 4-year-olds' poor performance on the DCCS.<br />

GENERAL DISCUSSION<br />

Study 1 involved three experiments that examined whether 3- to 4year-olds' errors on the DCCS can be<br />

attributed to age-related limitations on memory capacity. Several theories (e.g., Case, 1985, 1992; Gathercole,<br />

1998; Gordon & Olson, 1998; Morton & Munakata, 2002) suggest that age-related changes in short-term,<br />

active, or working memory are major determinants of children's performance on a wide variety of measures,<br />

including measures of executive function. In the DCCS, 3- to 4-year-olds may simply have difficulty keeping<br />

the postswitch rules in mind. Experiment 1 tested this memory account by comparing children's performance on<br />

the standard version of the DCCS to their performance on two new versions, the 4-Rules (unidimensional) and<br />

2+2-Rules (unidimensional) versions, that were similar to the standard version in that they required children to<br />

sort by four rules. If memory constraints are a major determinant of children's performance, then the two new<br />

versions should be at least as difficult as the standard version and possibly more difficult because children are<br />

told the four rules simultaneously. Results showed that performance was significantly worse in the standard<br />

version; indeed, most children failed the standard version but not the other two versions.<br />

Experiment 2 addressed the possibility that children did not really need to hold four rules in mind in order to<br />

succeed on the 4-Rules (unidimensional) and 2+2-Rules (unidimensional) versions. If children simply<br />

remembered the single relevant dimension, they could perhaps infer what went where in a given trial. In<br />

Experiment 2, children were given the 2+2-Rules (bidimensional, no overlap) version, in which they were told<br />

to sort first by two rules based on one dimension (e.g., color) and then by two rules based on the other<br />

dimension (e.g., shape). In this version, children needed to remember which cards to sort by color and which<br />

cards to sort by shape. Results revealed that 3- to 4-year-olds performed well on the 2 + 2- Rules<br />

(bidimensional, no overlap) version.<br />

Experiment 3 presented children with the 4-Rules (superordinate) version, which likely posed even greater<br />

memory demands than the 4-Rules versions used in Experiments 1 and 2 because it involved superordinate rules<br />

and a heterogeneous series of test cards. Nonetheless, children performed significantly better on the 4-Rules<br />

(superordinate) version than on the standard version of the DCCS. Taken together, findings from the three<br />

experiments provide strong evidence against a memory account of performance on the DCCS.<br />

The findings also help isolate what may be a crucial determinant of difficulty. In each of the modified versions<br />

of the DCCS, there was no conflict among rules and children did not have to sort the same test card in two<br />

different ways. Because each test card was uniquely associated with a different rule, children arguably did not