Programme

Programme

Programme

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The lengthened grade in Indo-European<br />

Thematic Conference (Arbeitstagung)<br />

of the Society for Indo-European Studies (Indogermanische Gesellschaft)<br />

Leiden, July 29-31, 2013<br />

Sponsored by:

Contents<br />

Introduction …… p. 3<br />

Addresses …….p. 4<br />

<strong>Programme</strong> …… p. 5<br />

Abstracts …… p. 8<br />

Topics for the Round Table discussion …… p. 44<br />

2

Introduction<br />

In the off-years of the four-yearly General Conference (Fachtagung) of the Society for Indo-<br />

European Studies, a thematic conference is hosted by a different university each year. The<br />

Leiden University Centre for Linguistics (LUCL) and its Chair of Comparative Indo-<br />

European Studies are grateful to the Society for granting the organization of the 2013<br />

Thematic Conference to Leiden. The conference will be held from 29 to 31 July.<br />

The topic of the meeting will be the lengthened grade, that is, the long vowels *ē and *ō of<br />

Proto-Indo-European. The origin and the phonetics of these vowels, as well as the<br />

grammatical functions which they had, are still very much disputed. The main aim of this<br />

conference is to make explicit on which points scholars of Indo-European agree and disagree<br />

in their interpretation of the available evidence.<br />

We are happy to see that our call for papers has been answered by many scholars from around<br />

the world, young and old, who are engaged in reconstructing the linguistic past of the Indo-<br />

European languages. The programme contains talks on all of the main branches of Indo-<br />

European, and on a wide variety of theoretical questions concerning the phonology and<br />

morphology of Proto-Indo-European. The conference will be closed by a Round Table<br />

Discussion, in which the main themes and various positions which one may take towards<br />

them will be debated by an expert panel. A selection of topics to be discussed by the panel can<br />

be found at the end of this booklet.<br />

This conference was preceded by the 8 th Leiden Summer School in Languages and Linguistics<br />

(15–26 July), which features Indo-European programmes for beginners and for advanced<br />

students, as well as specialized courses in various Indo-European branches.<br />

The organisation of this conference has been sponsored by Leiden University Fund (LUF),<br />

Brill Publishers, and the Leiden University Centre for Linguistics.<br />

Lucien van Beek<br />

Alwin Kloekhorst<br />

Alexander Lubotsky<br />

Michiel de Vaan<br />

Leiden, July 2013<br />

3

Addresses<br />

Academy Building (all lectures): Rapenburg 67-73, Leiden. Reception: 071 527 1210.<br />

Lipsius Building (lunch): Cleveringaplaats 1, Leiden. Reception: 071 527 2300 or 2500.<br />

Arsenaal Building (final dinner): Arsenaalstraat 1, Leiden. Phone: 071 527 2524/2539.<br />

Town Hall (reception on Tuesday): Stadhuisplein 1, Leiden. We will walk there together from<br />

the Academy Building after the final lecture on Tuesday afternoon.<br />

We will also walk together to the boat trip on Monday afternoon.<br />

For a convenient map of Leiden city centre, see the website of the Leiden Visitor Centre:<br />

http://portal.leiden.nl/uploads/tekstblok/vcl_kaart2012_def.pdf.<br />

4

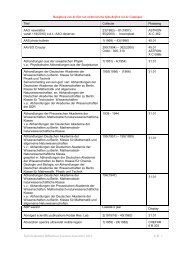

<strong>Programme</strong><br />

Sunday, July 28<br />

17:00 – 19:00 informal “meet and greet” with drinks and possibility to have dinner<br />

(Grand Café Van Buuren, Stationsweg 7)<br />

Monday, July 29<br />

08:30 – 09:45: Welcome and registration, Academy Building<br />

09:45 – 10:00: Opening<br />

Session 1: Indo-Iranian I<br />

10:00 – 10:30 Kümmel: The lengthened grade in the nominative singular<br />

10:30 – 11:00 Ittzés: Temporal augment and vr̥ ddhi-derivation in Indo-Iranian<br />

Coffee break: 11:00 – 11:20<br />

Session 2: Indo-Iranian II<br />

11:20 – 11:50 Kortlandt: Sigmatic and asigmatic long vowel preterit forms<br />

11:50 – 12:20 Dahl: Derivational modality? The rise (and fall) of the lengthened grade as a<br />

subjunctive marker in Vedic<br />

12:20 – 12:50 Šefčík: The fourth makes it whole? The reduced lengthened ablaut grade in Old<br />

Indo-Aryan<br />

Lunch break: 12:50 – 14:10<br />

Session 3: IE ablaut and root structure<br />

14:10 – 14:40 Melchert: “Narten formations” versus “Narten roots”<br />

14:40 – 15:10 Höfler: Notes on three “acrostatic” neuter s-stems<br />

15:10 – 15:40 Nielsen Whitehead: Root-structure and the occurrence of full and lengthened<br />

grade in PIE root nouns<br />

Tea break: 15:40 – 16:00<br />

Session 4: IE ablaut<br />

16:00 – 16:30 Gąsiorowski: Another long grade: Non-canonical ablaut involving PIE *ā<br />

16:30 – 17:00 Litscher: The Nominative Singular of *eh₂- and *ih₂- Stems<br />

17:00 – 17:30 Oettinger: Zu langstufigen Bildungen des Indogermanischen<br />

Evening programme: 18:15 – 19:15 Leiden round trip by boat<br />

Dinner (on own initiative): for information about restaurants, ask the organisation<br />

5

Tuesday, July 30<br />

Session 1: Various Topics<br />

09:30 – 10:00 Blažek: On the lengthening of verbal bases in Indo-European in an Afroasiatic<br />

perspective<br />

10:00 – 10:30 Panagl: ‘Expressive lengthening’ – linguistic reality or strange nightmare?<br />

10:30 – 11:00 Bichlmeier: Dehnstufen in der ‚Alteuropäischen Hydronymie’?<br />

Coffee break: 11:00 – 11:20<br />

Session 2: Greek and Slavic<br />

11:20 – 11:50 Steer: Zur Etymologie von griechisch κῆλα ‚Pfeile, Geschosse‘<br />

11:50 – 12:20 Willi: Ares the Ripper: From Stang’s Law to long-diphthong roots<br />

12:20 – 12:50 Reinhart: The derivation of Slavic imperfective verbs with lengthened grade<br />

Lunch break: 12:50 – 14:10<br />

Session 3: Balto-Slavic<br />

14:10 – 14:40 Yamazaki: Some Notes on the 3rd Person Future Forms in Lithuanian<br />

14:40 – 15:10 Villanueva Svensson: Tone variation among Baltic ia-presents<br />

15:10 – 15:40 Matasović: The accentuation of Balto-Slavic Vr̥ ddhi formations and the origin<br />

of the acute<br />

Tea break: 15:40 – 16:00<br />

Session 4: Tocharian and Albanian<br />

16:00 – 16:30 Hyllested: Unexpected lengthened grade in Albanian<br />

16:30 – 17:00 Malzahn: Surprise at length of Tocharian nouns<br />

17:00 – 17:30 Pinault: The lengthened grade in Tocharian nominal morphology<br />

Evening programme: 17:45 – 18:45 Reception by the mayor at the Town Hall<br />

Dinner (on own initiative): for information about restaurants, ask the organisation<br />

6

Wednesday, July 31<br />

Session 1: Germanic<br />

10:00 – 10:30 Lühr: The lengthened grade in Germanic hypocoristica<br />

10:30 – 11:00 Kroonen: Analogical lengthened grades in the Proto‐Germanic strong verbs<br />

Coffee break: 11:00 – 11:20<br />

Session 2: Szemerényi’s Law I<br />

11:20 – 11:50 Byrd: Accounting for the Absence of Expected Lengthened Grade:<br />

Szemerényi’s Law in Word-Medial Position<br />

11:50 – 12:20 Sandell: On the Phonetics and Phonology of Stang’s and Szemerényi’s Laws<br />

12:20 – 12:50 Keydana: Lengthened grade in Vedic root nouns: Szemerényi's Law and some<br />

of its implications<br />

Lunch break: 12:50 – 14:10<br />

Session 3: Szemerényi’s Law II<br />

14:10 – 14:40 Sukač: Szemerényi’s law and related issues<br />

14:40 – 15:10 Piwowarczyk: The Proto-Indo-European *-VTs# clusters and the formulation<br />

of Szemerényi’s Law<br />

15:10 – 15:40 Pronk: Szemerényi’s law: a critical survey of the evidence<br />

Tea break: 15:40 – 16:00<br />

Session 4: 16:00 – 17:00 Round Table<br />

16:00 – 17:00 Round Table discussion (Kortlandt, Kümmel, Pinault)<br />

Evening programme: 18:30 – end Final Dinner (Arsenaal building)<br />

7

Abstracts<br />

8

Dehnstufen in der ‚Alteuropäischen Hydronymie’?<br />

Harald Bichlmeier, Sächsische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig, Arbeitsstelle Jena<br />

Erst seit kurzem gibt es Bemühungen, die Forschungen zur ‚Alteuropäischen Hydronymie’<br />

auf das heute in der Indogermanistik übliche Niveau zu heben. Im Rahmen dieser<br />

Bemühungen sind auch einige Flussnamen in die Diskussion geraten, für die auch einmal die<br />

Möglichkeit in Betracht gezogen wurde, dass die rekonstruierte Vorform eine Dehnstufe<br />

enthalten haben könnte. Es sind dies u.a. die Flussnamen Sawa (in Polen) sowie die Naab in<br />

Nord-Ost-Bayern. In die Diskussion mit aufgenommen werden müssen auch die<br />

Namensvetterin des polnischen Flusses, die Sava/Save sowie der morphologisch parallel<br />

gebaute Name der Drava/Drau.<br />

Der Name der Sava/Save könnte eine Dehnstufe enthalten haben. Wenn der Name<br />

aber, was wahrscheinlich ist, parallel zu dem der Drava/Drau gebaut war, ist dies abzulehen.<br />

War die Bildung indes tatsächlich dehnstufig, lag also eine alte Vr̥ ddhi-Ableitung vor, müsste<br />

die ursprüngliche Bedeutung kollektivisch ‚Gebiet entlang des Flusses’ o.ä. bedeutet haben.<br />

Die Benennung des Gebiets müsste dann sekundär auf den Fluss übertragen worden sein.<br />

Gleiches gilt mithin zunächst für die polnische Sawa. Da aber für den polnischen Flussnamen<br />

die Erklärung mittels einer romanischen Zwischenstufe entfällt, bleibt die genannte<br />

Möglichkeit einer Vr̥ ddhi-Ableitung bestehen, die Übertragung der Bezeichnung vom Gebiet<br />

entlang des Flusslaufs auf den Fluss selbst muss in Kauf genommen werden.<br />

Ausgeschlossen werden kann jedoch, dass der slawische Langvokal automatisch bei<br />

der Übernahme ins Slawische aus einem alten Kurzvokal entstanden ist (so Udolph 2007 im<br />

Gefolge älterer Arbeiten).<br />

Auch für die oberpfälzische Naab wurde schon eine dehnstufige Bildung angenommen<br />

(Bammesberger 2001/2002): Es sei späturidg. *nōb h -ā- > kelt. *nōbā- anzusetzen. Dem<br />

widerspricht in diesem Falle jedoch die Mundartform des Flussnamens in den Ortsdialekten,<br />

die [nọ̄ ] lautet: Diese Form kann nur aus sekundär in offener Silbe gedehntem Kurzvokal ahd.<br />

mhd. -a- entstanden sein: Die mutmaßlich aus dem Keltischen ins Westgermanische<br />

übernommene Form des Namens muss also einen Kurvokal gehabt haben, es ist späturidg.<br />

*nob h ā- anzusetzen.<br />

Dehnstufen können in der ‚Alteuropäischen Hydronymie’ nur in den seltensten Fällen<br />

sicher nachgewiesen werden. Wenn sie vorliegen, sind jedoch in unterschiedlichem Maße<br />

Zusatzannahmen besonders hinsichtlich der Semantik zur Erklärung notwendig.<br />

Literatur in Auswahl:<br />

Bammesberger, Alfred (2001/2002): Der Name der Amper: Eine Nachlese. In: Blätter für<br />

oberdeutsche Namenforschung 38/39, S. 47–51.<br />

Bichlmeier, Harald (2010): Moderne Indogermanistik vs. traditionelle Namenkunde, Teil 3:<br />

Traun, Raab und Auders. In: Österreichische Namenforschung 38, 2010, S. 104–113.<br />

Bichlmeier, Harald (2011a): Einige grundsätzliche Überlegungen zum Verhältnis von<br />

Indogermanistik und voreinzelsprachlicher resp. alteuropäischer Namenkunde mit einigen<br />

Fallbeispielen (Moderne Indogermanistik vs. traditionelle Namenkunde, Teil 1). In:<br />

Namenkundliche Informationen 95/96, 2009[2011], S. 173–208.<br />

Bichlmeier, Harald (2011b): Moderne Indogermanistik vs. traditionelle Namenkunde, Teil 2 –<br />

Save, Drau, Zöbern. In: Ziegler, Arne / Windberger-Heidenkummer, Erika (Hgg.):<br />

Methoden der Namenforschung. Methodologie, Methodik und Praxis. [= Akten der 6.<br />

Tagung des Arbeitskreises für bayerisch-österreichische Namenforschung (ABÖN), Graz,<br />

12.–15.5.2010] Berlin: Akademie Verlag 2011, S. 63–87.<br />

9

Bichlmeier, Harald (2012): Einige ausgewählte Probleme der alteuropäischen Hydronymie<br />

aus Sicht der modernen Indogermanistik – Ein Plädoyer für eine neue Sicht auf die Dinge.<br />

In: Acta Linguistica Lithuanica 66, 2012, S. 11–47.<br />

Bichlmeier, Harald (2013): Bayerisch-österreichische Orts- und Gewässernamen aus indogermanistischer<br />

Sicht – Teil 3: Zusammenfassung bisheriger Forschungsergebnisse zu altbayerischen<br />

Flussnamen sowie einige indogermanistische Anmerkungen zu den<br />

Flussnamen Ammer/Amper und Naab. In: Simbeck, Katrin / Winner, Martina (Hgg.):<br />

Namen in Altbayern. (Regensburger Studien zur Namenforschung 8) Regensburg: vulpes<br />

2013. (im Druck)<br />

ESSZI: Snoj, Marko (2009): Etimološki slovar slovenskih zemljepisnih imen. Ljubljana.<br />

Udolph, Jürgen (2007): Alteuropa in Kroatien: Der Name der Sava/Save. In: Folia<br />

Onomastica Croatica 12-13, 2003-2004[2007], S. 523-548.<br />

10

On the lengthening of verbal bases in Indo-European in an Afroasiatic perspective<br />

Václav Blažek, Masaryk University, Brno<br />

In morphology of the Indo-European verb following formations operate with the lengthened<br />

root vowel:<br />

1a. *C 1 ḗC 2 - acrodynamic root present in singular of indicative/injunctive active (LIV 14).<br />

1b. *C 1 ḗC 2 -s- sigmatic aorist in singular of indicative/injunctive active (LIV 20).<br />

2. *C 1 ṓC 2 -i̯ e- causative-iterative with the suffix -i̯ e/o- forming also present (LIV 23, 19).<br />

Note: C 1 = (s)T(R), C 2 = (R)T, R = i̯ , u̯ , l, r, m, n.<br />

(i) The Indo-European lengthened singular of present & sigmatic aorist in -ē- corresponds to<br />

the Beja (North Cushitic) lengthened singular present in -ī-.<br />

√-dir- "to kill":<br />

1.sg. andī́r, 2.sg.m. té-n-dīr-a, 2.sg.f. té-n-dīr-i, 3.sg.m. e-n-dī́r, 3.sg.f. te-n-dī́r;<br />

1.pl. nḗ-dír, 2.pl. tē-dír-na, 3.pl. ē-dír-na.<br />

√-dibil- "to twine, collect, gather":<br />

1.sg. a-dambı̄́l, 2.sg.m. dámbı̄ l-a, 2.sg.f. dámbı̄l-i, 3.sg.m.f. dambı̄́l;<br />

1.pl. ne-dabíl, 2.pl. te-dabíl-na, 3.pl. e-dabíl-na.<br />

(ii) The Indo-European lengthened ō-causative-iterative is formally comparable with the<br />

Afroasiatic intensive formations in -ā-:<br />

Lengthening in frequentative / intensive in Beja, which is used, if a transitive verb has a plural<br />

object:<br />

√-dir- "to kill" vs. frequentative / intensive √-dār- "to massacre, cause carnage"<br />

perfect: 1.sg. a-dā́ r, 2.sg.m. te-dā́ r-a, 2.sg.f. te-dā́ r-i, 3.sg.m. e-dā́ r, 3.sg.f. te-dā́ r;<br />

1.pl. ne-dā́ r, 2.pl. te-dā́ r-na, 3.pl. te-dā́ r-na.<br />

√-dibil- "to twine, collect, gather" vs. frequentative -dābil-:<br />

perfect: 1.sg. a-dā́ bil, 2.sg.m. te-dā́ bil-a, 2.sg.f. te-dā́ bil-i, 3.sg.m. e-dā́ bil, 3.sg.f. te-dā́ bil;<br />

1.pl. ne-dā́ bil, 2.pl. te-dā́ bil-na, 3.pl. te-dā́ bil-na.<br />

ā-present in East Cushitic:<br />

Somali yi-mād-da "he comes" : yi-mid "he came"<br />

Semitic conative: Arabic qātala "he tried to kill", Geez taqātala "killed one another, maked<br />

war".<br />

Berber: Tuareg of Ahaggar impf. ikrǝs "ties" (*yakris) : perf. intensive ikrâs (*yukrâs): impf.<br />

positive intensive ikârräs (*yikârras);<br />

Chadic: Daffo (West Chadic) mwaát "dies" : mot "died"; shwaáh "drinks" : shoh "drank;<br />

Sokoro (East Chadic) nā bā "I go" : nā bē "I went".<br />

11

Accounting for the Absence of Expected Lengthened Grade:<br />

Szemerényi’s Law in Word-Medial Position<br />

Andrew Miles Byrd, University of Kentucky<br />

Szemerényi’s Law (SzL), as is well known, was a phonological process of consonant loss<br />

with subsequent compensatory lengthening (CL) in word-final position, reconstructed for<br />

early PIE. While typically cited as a rule of s-loss, Szemerényi (1970) also recognized this<br />

process to include laryngeals as target consonants, which we may conceive as taking part in a<br />

more general process of fricative deletion.<br />

In this paper I will demonstrate that SzL not only targeted those segments in wordfinal<br />

position; it also targeted them word-medially. Cf. *u̯ erh 1 d h h 1 o- > Lat. verbum, Hesych.<br />

ért h ei ‘speaks’. Of course, such laryngeal deletion is usually attributed to the CHCC > CCC<br />

rule. However, there are a number of strong counterexamples (*ḱerh 2 srom > Lat. cerebrum<br />

‘brain’), and as I have argued on multiple occasions, the CHCC > CCC rule was rather<br />

PH.CC > P.CC (where P = obstruent), driven by violations of syllable structure.<br />

SzL ceased to be a productive rule within late PIE, as evidenced by the<br />

reconstructability of *g w énh 2 ‘woman’, *wih 1 roms, *sals ‘salt’ and *séms ‘one’. It is in this<br />

way that the on-again, off-again reconstructability of laryngeal loss in the sequence RH$<br />

(with < $ > marking a syllable boundary) may be directly explained. But if this truly were<br />

SzL, should we not find lengthened grade in the initial syllables of a form such as **u̯ ērd h h 1 o-<br />

(< *u̯ erh 1 d h h 1 o-)? It will be argued that no CL occurs due to the (P)IE tendency to avoid<br />

superheavy syllables (syllables consisting of more than two morae) in medial position,<br />

resulting in the loss of a mora. This tendency also underlies Schwebeablaut, Osthoff’s Law,<br />

the replacement of certain e-grade oblique stems with ø-grade forms, and Sievers’ Law.<br />

12

Derivational modality? The rise (and fall) of the lengthened grade as a subjunctive<br />

marker in Vedic<br />

Eystein Dahl, University of Bergen<br />

This paper explores the use of the lengthened grade in the so-called strong endings in the<br />

Vedic middle subjunctive paradigm. The inherited 1 st dual and plural middle subjunctive<br />

forms of the type sacāvahe, yajāmahe were replaced by innovative forms like sacāvahai,<br />

yajāmahai which probably arose by analogical influence from 1 st singular middle subjunctive<br />

forms such as sacai, yajai. The paradigm resulting from this process raises a number of<br />

intriguing questions with regard to how the innovative subjunctive forms were generated<br />

synchronically. Specifically, there is an obvious apophonical relationship between forms like<br />

yaje, yajase, yajate etc. on the one hand and yajai, yajāsai, yajātai etc. on the other, the latter<br />

forms ultimately seeming to represent a kind of double vṛddhi-derivation which affects the<br />

penultimate as well as the last syllable. This use of apophony in the verbal paradigm is<br />

remarkable, as processes of this kind, particularly the alternation between full grade and<br />

lengthened grade, mostly serves to affect the derivational base, cf. e.g. so-called Narten<br />

presents like stauti/stavat or sigmatic aorists like ajais/jeṣat. Given the systematic<br />

correspondences between the subjunctive and the indicative in the middle paradigm, it is<br />

significant that the active paradigm of the subjunctive has a far less obvious or systematic<br />

relation to the indicative. From this perspective, the apparent rise in Vedic of a secondary type<br />

of derivational modality employing the lengthened grade as a subjunctive marker seems to<br />

have resulted in a split in the subjunctive paradigm, whereby the active subparadigm was<br />

generated by means of one more or less coherent set of rules while the middle subparadigm<br />

was generated by one simple derivational rule. These two factors, the paradigm split and the<br />

synchronically exceptional derivation pattern of the middle subjunctive forms, may ultimately<br />

have caused the subjunctive to disappear.<br />

13

Another long grade: Non-canonical ablaut involving Proto-Indo-European *ā<br />

Piotr Gąsiorowski, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań<br />

The only undisputed source of PIE a-vocalism is *e coloured by an adjacent *h 2 . Assuming<br />

the archaic character of Narten ablaut (*ḗ : *é), and the resistance of long *ē to colouring, we<br />

can expect cases of *h 2 ēC-/*h 2 aC- and *Cēh 2 -/*Cah 2 - (> *ēC-/*aC-, *Cē-/*Cā-). Such an<br />

analysis does not predict alternations like *CāC-/*CaC-, which are nevertheless supported by<br />

the comparative evidence (e.g. *u̯ ā́ ĝ- /*u̯ áĝ- ‘break’). They are difficult to explain with the<br />

help of the laryngeal theory alone, or require questionable assumptions.<br />

I shall argue that the *ā́ : *á alternation is not a secondary effect of laryngeal colouring<br />

but an inherited pattern akin to *ḗ : *é (as well as *ó : *é), and deserves to be treated as a<br />

separate subtype of full-vowel ablaut. I shall try to provide examples of this pattern, define<br />

morphophonological constraints on its occurrence, and criteria for deciding which instances<br />

of *ā : *a are due to it rather than some secondary source of a-vocalism.<br />

Selected bibliography:<br />

Beekes, Robert S. P. 1988. PIE. RHC- in Greek and other languages. Indogermanische<br />

Forschungen 93, 22-45.<br />

Jasanoff, Jay H. 2003. Hittite and the Indo-European verb. Oxford: OUP.<br />

Kümmel, Martin Joachim. 1998. Wurzelpräsens neben Wurzelaorist im Indogermanischen.<br />

Historische Sprachforschung 111, 191-208.<br />

Lubotsky, Alexander. 1989. Against a Proto-Indo-European phoneme *a. In: Theo<br />

Vennemann (ed.), The new sound of Indo-European: essays in phonological<br />

reconstructions, Berlin–New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 53-66.<br />

Schindler, Jochem. 1972. L’Apophonie des nom-racines en indo-européen. Bulletin de la<br />

société de lin istiq e de Paris 67, 31-68.<br />

de Vaan, Michiel. 2004. ‘Narten’ roots from the Avestan point of view. In: Adam Hyllested,<br />

Anders Richardt Jørgensen, Jenny Helena Larsson & Thomas Olander (eds.), Per<br />

Aspera Ad Asteriscos. Studia Indogermanica in honorem Jens Elmegard Rasmussen<br />

sexagenarii Idibus Martiis anno MMIV, Innsbruck: Innsbrucker Beiträge zur<br />

Sprachwissenschaft, 591-599.<br />

14

Notes on three “acrostatic” neuter s-stems<br />

Stefan Höfler, University of Vienna<br />

The neuter s-stem nouns usually reflect full grade in the root throughout the whole paradigm,<br />

whereas the suffix shows ablaut from o-grade in the nom.-acc. sg. to e-grade in the oblique<br />

stem. Based on his interpretation of different relic forms, Schindler (1975) argued that this<br />

paradigm (e.g. *u̯ ék u̯ -os : *u̯ ék u̯ -es- ʻword, speechʼ) replaced an older proterokinetic pattern<br />

(e.g. *u̯ ék u̯ -s : *u̯ k u̯ -és-). Even though some aspects of his argumentation have been criticized<br />

until recently, Schindler’s assumptions remain the basis for today’s communis opinio<br />

concerning the ablaut pattern of neuter s-stem nouns.<br />

At the end of his article, Schindler mentioned that there could have been s-stems of the<br />

acrostatic type B (i.e. R(ḗ)-S(z) : R(é)-S(z)-) as well, citing forms that reflect lengthened grade<br />

in the root and pairs with root vowel alternations. Schindler’s mere floating the possibility of<br />

their existence has consequently led to a broad acceptance of this type of neuter s-stems<br />

among many scholars to this day. In 1994, Schindler then suggested the existence of “Narten”<br />

roots – roots that show a systematic ablaut ē/ĕ in verbal and nominal formations instead of the<br />

common ĕ/z pattern, thus offering an alternative explanation for long-vowel s-stems. While<br />

some of his examples have been convincingly explained without the concept of “Narten”<br />

roots, the mystery of “acrostatic” s-stems remains widely unsolved.<br />

Taking a closer look at three of the most interesting examples (PIE *mḗd-os, *sḗd-os<br />

and *h 1 ḗd-os), this paper shall question both the concept of “acrostatic” neuter s-stems and the<br />

role of “Narten” roots in their respect. The aim of this paper is to examine the different<br />

possible explanations for the three s-stems, and, in a broader perspective, the parallel nominal<br />

and verbal formations of the underlying roots, and thus to re-evaluate the phenomenon of<br />

long-vowel s-stems.<br />

15

Unexpected lengthened grade in Albanian<br />

Adam Hyllested, University of Copenhagen<br />

Unexpected and otherwise undocumented lengthened grade shows up in Albanian in an<br />

unusually large number of cases when compared to the other Indo-European branches. While<br />

it is of course possible that the PIE lengthened grade stayed productive and developed a wider<br />

use in Pre-Proto-Albanian (as already suggested by Jokl 1916), the attested Albanian forms in<br />

fact do not seem to reveal any clear functional patterns. Most cases are therefore assigned<br />

individual explanations (to the extent that they are explained at all). The verb vesh ‘wear, put<br />

on’, for example, seemingly from *u̯ ōs-, has been identified as a “Narten-root”, while Huld<br />

(1984) asserts as the source and old causative *u̯ os-eie- where *o > *a that regularly<br />

undergoes umlaut to -e-.<br />

The long vowel in njoh ‘to know’ is supposed to either reflect < *ĝnēh₃-skō with<br />

lengthened grade analogical from the s-aorist, or the outcome of a zero-grade *ĝn̥ h₃-skō.<br />

Among nominal forms, derë ‘door’ has been interpreted as an old collective *d h u̯ ōr-h₂, a<br />

solution which, although perhaps not immediately compelling in either case, could apply to<br />

dorë ‘hand’ as well (if from *ĝ h ēsr̥ -h₂; Huld 1984, Jens Elmegård Rasmussen p.c.). While<br />

possible, hardly any of the morphological explanations are valid for more than a couple of<br />

items each, and none of them can therefore clarify why particularly Albanian displays so<br />

many cases of secondary lengthened grade both among its verbal and nominal forms.<br />

A phonological explanation for dorë going back to Haebler 1967 has proven<br />

increasingly popular (embraced by most recent works such as Demiraj 1997, Orel 2000, de<br />

Vaan 2004, Matzinger 2006, Vermeer 2008, Matasović 2012), namely that -o- reflects<br />

compensatory lengthening arisen by the loss of -s- in the old consonant cluster: *ĝ h esr- ><br />

*ĝ h ēr- > *dēr- > *dōr- > dor-. In this paper I will try to show that phonological explanations<br />

are indeed preferable in most cases where Albanian deviates from other IE languages, and that<br />

there is no need to assert an increased morphological productivity of the lengthened grade in<br />

Pre-Proto-Albanian.<br />

Crucially, unexpected lengthening occurs almost exclusively preceding consonant<br />

clusters, very often heavy ones (consisting of three consonants or more) where at least one<br />

consonant has disappeared. Thus, we can assert compensatory lengthening applying to e.g.<br />

boj ‘to drive, to mate’ < PPAlb. *bāgnja- < PIE *b h eg w - ‘to run’; huaj ‘foreign, strange’ <<br />

PPAlb. *ksōnwja- < PIE *ksen-u̯ -; korrë ‘harvest’ < PPAlb. *kārsnā- < PIE *kerts-neh₂; quaj<br />

‘call, give a name’ < PPAlb. *klōusnja- < PIE *kleu̯ s-; sorrë ‘crow’ < PPAlb. *čārsnā- < PIE<br />

*k w ers-neh₂; shoh ‘to see’ < *sāska- < PIE *sek w -skō; thom ‘to say’ < PPAlb. *tsānsmi < PIE<br />

*kens-; and zorrë ‘gut’ < PPAlb. *džārnā- < PIE *g w erh₃-neh₂.<br />

The possibility remains that at least some of the relevant forms never had long vowels<br />

in the first place. Alb. e is already known to be one regular (conditioned) outcome of PIE *e,<br />

and *o via umlaut. The case of shoh ‘to see’ is particularly interesting in this respect since a)<br />

the lengthened grade is morphologically odd in -sḱ-presents; b) a sequence *-k w -sḱ- was<br />

probably already reduced to *-sḱ- in PIE (cf. *pr̥ sḱō < *pr̥ k-sḱō ‘ask’); and (c), in fact we find<br />

no other examples of -e- following sh < PIE *s.<br />

References:<br />

Demiraj, Bardhyl, 1997: Albanische Etymologien. Untersuchungen zum Albanischen<br />

Erbwortschatz. Amsterdam / Atlanta: Rodopi.<br />

Haebler, Claus, 1967: Review of Hamp. – Die Sprache 13: 79-84.<br />

Hamp, Eric, 1966: “The Position of Albanian”. – Henrik Birnbaum & Jaan Puhvel: Ancient<br />

Indo-European Dialects.University of California Press.<br />

Huld, Martin, 1984: Albanian Etymologies. Bloomington: Slavica.<br />

16

Jokl, Norbert, 1916: Studien zur albanesischen Grammatik 4. Indogermanische Forschungen<br />

37: 199-220.<br />

Matasović, Ranko, 2012: A grammatical sketch of Albanian for students of Indo-European.<br />

Zagreb.<br />

Matzinger, Joachim, 2006: Der Altalbanische Text Mbsuame e Kreshtere (Dottrina cristiana)<br />

des Leke Matrenga von 1592: Eine Einfuhrung in die albanische Sprachwissenschaft.<br />

Dettelbach: J.H. Röll.<br />

Orel, Vladimir, 2000: A concise historical grammar of the Albanian language: reconstruction<br />

of Proto-Albanian. Leiden: Brill.<br />

de Vaan, Michiel, 2004: “PIE *e in Albanian”. – Die Sprache 44, 1: 70-85.<br />

Vermeer, Willem, 2008: “The Prehistory of the Albanian Vowel System: A Preliminary<br />

Exploration”. – Evidence and Counter-evidence. Festschrift Frederik Kortlandt, vol. 1<br />

SSGL 32. Amsterdam / New York: Rodopi. Pp. 591-608.<br />

17

Temporal augment and vr̥ ddhi-derivation in Indo-Iranian<br />

Máté Ittzés, Eötvös-Loránd-University, Budapest<br />

The paper seeks to answer the question how augmented forms of verb stems with initial i and<br />

u were formed in Old Iranian, i.e. Avestan and Old Persian.<br />

First, the Old Indo-Aryan rule of temporal augment will be shortly described, which<br />

consists in the vr̥ ddhi of the initial vowel. However, such a general rule cannot be assumed for<br />

Old Iranian (or Proto-Indo-Iranian), since it has to be interpreted as an inner-OIA<br />

development. Unfortunately, no relevant Avestan and Old Persian forms are directly attested.<br />

In OIA the treatment of the initial vowel in augmented forms is parallel to the rule<br />

observed in nominal vr̥ ddhi-derivation. It can be assumed that a similar parallism existed in<br />

the Old Iranian languages. Nominal vr̥ ddhi is relatively well known in Avestan, i.e. simple<br />

vowels are replaced by guṇa and guṇa vowels probably by vr̥ ddhi, although the latter is not<br />

attested. This means that Avestan probably had augmented forms with short (guṇa)<br />

diphthongs.<br />

The exact rules of Old Persian nominal vr̥ ddhi have been unclear. Most scholars<br />

assume that, similarly to OIA, both simple and guṇa vowels were replaced by vr̥ ddhi. Since<br />

there is broad consensus now that, in comparison to OIA, Avestan preserved the original<br />

Proto-Indo-Iranian derivational mechanism, this would have to be regarded as a parallel, but<br />

independent, innovation of OP and OIA. The crucial form is the month name θ-a-i-g-r-č-i-. I<br />

will show that, contrary to the view that the first syllable’s long diphthong (if it is really a<br />

long diphthong) must be the vr̥ ddhi-replacement of the simple vowel i, it may also be<br />

interpreted otherwise (i.e. *θigra- → *θaigraka- → θāigrači-). This means that Old Persian<br />

rather had an Avestan-like rule of vr̥ ddhi-derivation (and thus an Avestan-like temporal<br />

augment).<br />

18

Lengthened grade in Vedic root nouns: Szemerényi's Law and some of its implications<br />

Götz Keydana, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen<br />

The lengthened grade in the nom.sg. of non-neuter root nouns and some primary derivatives is<br />

often explained as a result of compensatory lengthening. The most prominent case in point is<br />

Szemerényi's Law. In this talk I discuss the methodological premises of this law and look into<br />

possible explanations for the alleged change.<br />

In the first part I show that due to its logical structure Szemerényi's Law is not a sound<br />

law sensu stricto. I then proceed to discuss various phonological scenarios for the law given<br />

in the literature. Compensatory lengthening being the most promising I give a detailed<br />

account of this process in word-final Vrs-sequences. Clusters of this type are indeed prone to<br />

undergo change based on hypocorrection and often resulting in a lengthened preceding vowel.<br />

However, hypocorrection is only possible if the target of the deletion is adjacent to the vowel.<br />

Thus, the only outcome a phonological change can account for is † V̅ s. I propose a solution to<br />

this problem based on a morphophonological repair triggered by recoverability issues and / or<br />

paradigm uniformity. In this scenario, lengthening became opaque and could easily be<br />

reanalyzed, thus starting a new career as a morphological marker for the n.sg.<br />

19

Sigmatic and asigmatic long vowel preterit forms<br />

Frederik Kortlandt, Leiden University<br />

On various occasions I have argued that sigmatic and asigmatic long vowel preterit forms<br />

originated from monosyllabic lengthening in Proto-Indo-European. This view has generally<br />

been disregarded or misrepresented until Kümmel’s recent article (2012). According to my<br />

view, lengthened grade was originally limited to the 2nd and 3rd sg. active forms of both the<br />

sigmatic and the root aorist injunctive. I have claimed that the original distribution was<br />

essentially preserved in the Vedic sigmatic aorist injunctive, but not in the corresponding<br />

indicative, where lengthened grade was generalized, e.g. 1st sg. jeṣam vs. ajaiṣam, 1st pl.<br />

jeṣma vs. ajaiṣma, also śramiṣma vs. atāriṣma. In the root aorist, lengthened grade was<br />

preserved e.g. in Tocharian B śem ‘came’ < *g w ēm-, lyāka ‘saw’ < *lēǵ-, Latin vēnit, lēgit,<br />

Gothic qemun, Albanian mblodhi, Greek ἔσβη ‘(the fire) went out’ < *-g w ēs-, Vedic āraik<br />

‘left’ < *-lēik w -.<br />

Kümmel (2012) disregards the possibility of an apophonic difference between<br />

injunctive and indicative forms. Starting from the presupposition that the active forms of the<br />

sigmatic aorist always had a lengthened grade root vowel, he has to explain away all contrary<br />

instances. Narten presents are a recent development in Vedic, where the athematic present of<br />

the root stu- is secondary and the oldest paradigms of this root are the thematic middle present<br />

and the active subjunctive. The only lengthened grade forms of this root in the Rgveda are the<br />

injunctive staut (7th maṇḍala) and the imperfect astaut (10th maṇḍala). What was the model<br />

for their creation? I think that it was the monosyllabic form of the root aorist injunctive, which<br />

appears to have been preserved in the indicatives RV akrān, asyān, āraik, acait, aśvait,<br />

adyaut of the roots krand-, syand-, ric-, cit-, śvit- and dyut-.<br />

20

Analogical lengthened grades in the Proto‐Germanic strong verbs<br />

Guus Kroonen, Copenhagen University<br />

Proto-Germanic had four short vowels, *a, *e, *i, *u, and four long vowels, *ē, *ī, *ō, *ū.<br />

PGm. *ē is traditionally assumed to have had a phonetic value *[ǣ], developing into *ā in<br />

West Germanic and to *ē in Gothic. However, new evidence suggests that *ē functioned as a<br />

secondary lengthened grade of *a in the so-called verbal iterative system. This points to an<br />

original Proto-Germanic pronunciation *[ā].<br />

The Proto-Germanic iterative system consists of a highly productive derivational<br />

pattern with which any full‐grade strong verb could be given a zero‐grade iterative with a<br />

root-final geminate, cf. G schneiden : schnitzen ‘to cut’ (see recently Kroonen 2012). It has in<br />

recent years come to light that the reverse process, i.e. derivation from iteratives to strong<br />

verbs, occurred as well. Back-formed strong verbs typically inherit the geminate of the<br />

iterative (Lühr 1988: 351ff., Kroonen 2011: 106-112). Also, iteratives with u‐vocalism<br />

produced strong verbs with long *ū analogically after verbal pairs with *ī : *i ablaut, cf. G<br />

zauchen : zucken ‘to pull’ (cf. Lat. ducere, ibid. 112-117).<br />

A possibility that has not yet been explored is that some other iterative verbs, namely<br />

those with a-vocalism, may have similarly given rise to their own class of strong verbs. By<br />

assuming that this class, in analogy to those with long *ī and *ū, received a long *ā in their<br />

roots, a number of formally and etymologically intricate formations, e.g. Go. slepan ‘to<br />

sleep’, Go. tekan ‘to take’ and MHG zāfen ‘to tear’, can be satisfactorily accounted for.<br />

Literature:<br />

F. Kortlandt, 2011, Where have all the aorists gone?, Amsterdamer Beiträger zur älteren<br />

Germanistik 67.<br />

G. Kroonen, 2012, Reflections on the o/zero-ablaut of the Germanic iterative verbs. In: H.<br />

Craig Melchert (ed.), The Indo-European Verb, 191-200. Wiesbaden.<br />

G. Kroonen, 2011, The Proto‐Germanic n‐stems. Amsterdam – New York.<br />

R. Lühr, 1988, Expressivität und Lautgesetz im Germanischen. Heidelberg.<br />

D. Ringe, 2006, From Proto‐Indo‐European to Proto‐Germanic. Oxford.<br />

21

The lengthened grade in the nominative singular<br />

Martin Joachim Kümmel, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena<br />

The lengthened grade sometimes appears in single forms of nominal paradigms, the best<br />

established case being the nominative singular of athematic paradigms. However, the<br />

explanation of the phenomenon is controversial: One approach assumes that the lengthening<br />

originally came up in forms where *-s was lost after resonants ( “Szemerényi’s law”) and was<br />

only later taken over by other stems (cf., e.g., Szemerényi 1970: 109ff.). Other approaches<br />

doubt such a connexion to the loss of *-s: Rasmussen (1978: 74-79; 1989: 139-142, 251ff.)<br />

assumed a lengthening effect of the original nominative ending **-z, while Beekes (1985:<br />

151-164) rejects any connection with the ending *-s and assumes two different sources:<br />

lengthening before final resonants in originally s-less nominatives, and lengthening in<br />

monosyllables.<br />

For the assessment of the different approaches it is important to keep in mind what<br />

data the reconstructed distribution is based upon. Some reconstructions crucially depend on a<br />

lengthened grade attested in Indo-Iranian; e.g., the reconstruction *djḗws ‘sky; day’ is mainly<br />

based on Vedic dyáuṣ. However, the distribution of lengthened grades and full grades in Indo-<br />

Iranian was strongly affected by the effects of Brugmann’s Law turning many o grades into<br />

synchronic lengthened grades. In this paper I will examine the synchronic distribution and<br />

history of long grade and full grade in Indo-Iranian noun inflection and the consequences of<br />

these findings for the reconstruction of the nominative singular in PIE, It will be argued that<br />

these data support the theory that the lengthened grade originally was in complementary<br />

distribution with overt *-s.<br />

References:<br />

Beekes, Robert S. P. (1985). The Origins of the Indo-European Nominal Inflection Innsbruck.<br />

Rasmussen, Jens Elmegård (1978): Zur Morphophonemik des Urindogermanischen. In:<br />

Collectanea Indoeuropaea I, ed. B. Čop et al., Ljubljana, 59-143.<br />

Rasmussen, Jens Elmegård (1989). Studien zur Morphophonemik der indogermanischen<br />

Grundsprache. Innsbruck.<br />

Szemerényi, Oswald (1970). Einführung in die vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft. Darmstadt.<br />

22

The Nominative Singular of *eh 2 - and *ih 2 - Stems<br />

Roland Litscher, Universität Zürich<br />

The usual reconstruction of PIE *eh 2 - and *ih 2 -stem nominatives as *-ah 2 (

The lengthened grade in Germanic hypocoristica<br />

Rosemarie Lühr, Humboldt Universität zu Berlin<br />

Among the Germanic n-stems there is a group of nouns which show a lengthened grade *ē,<br />

*ū, *ō followed by long voiced obstruents, MHG tāpe ‘paw’ (*dēbban-), OHG scuobba<br />

‘scale’ (*skōbbōn-). Double voiced obstruents behind long vowels are not due to sound laws.<br />

According to Kluge’s law, only voiceless stops arise from assimilation of n to a preceding<br />

obstruent. Kluge himself explained the variation of single and double obstruents by analogy.<br />

Despite criticisms of these “associationen” by Kauffmann, Lühr, van Helten, Rasmussen, this<br />

view is recently accepted by Kroonen. However, in the case of alternation opacity of<br />

allomorphemes with *þ : *tt resp. *đ : tt, one would rather expect a leveling to *t : *tt. Hence,<br />

another explanation of the long voiced obstruents must be found. In a first step, it has to be<br />

proven whether the connection of long vowels and long voiced stops is compatible with the<br />

Germanic syllable structure. The investigation is based on metrical phonology. The next<br />

investigation step concerns the meaning of the words with lengthened grade and long voiced<br />

stops in Germanic. As sound symbolism and expressivity play an important role in the<br />

Germanic lexicon, it is to be demonstrated to what extent such mental phenomena could have<br />

caused this phonetically odd mixture. Hereby the status of lengthened grades must be settled.<br />

It is posited that the long vowels are inherited in Germanic, but in front of long voiced stops<br />

they have the function to reinforce expressivity. Though the Germanic syllable structure<br />

forbids such super-heavy syllables, the lengthened grade is retained. The function of<br />

reinforcing expressivity by the lengthened grade is a special feature of the Germanic branch<br />

of the Indo-European languages.<br />

24

Surprise at length of Tocharian nouns<br />

Melanie Malzahn, University of Vienna<br />

The Tocharian languages reflect lengthened grades in roots within the verbal and nominal<br />

system. As for root apophony, on the one hand we find lengthened grades of roots in<br />

athematic nouns that do not come as a surprise at least to the followers of the Schindler<br />

School. Here belongs the TA dual form śanweṃ ‘jaws’ from *ĝēn- that can be derived from<br />

the paradigm of an acrostatic u-stem (as per Nikolaev, 2010, 1-18). Similarly, the ē-grade i-<br />

stem TB yel, TA wal < *wēl-i- ‘worm’ is reminiscent of the Greek ē-grade i-stem δῆρις<br />

‘battle’. The same applies to lengthened-grade thematic nouns and respective n- and eh 2 -stem<br />

derivatives, since PIE had denominative o-stems denoting appurtenance formed by<br />

vrddhisation. Here seems to belong TB yente, TA want ‘wind’ < *h 2 u̯ ēh 1 -n̥ to- (as per<br />

Schindler, 1994, 399; Widmer, 1997, 28), TB yerpe ‘orb’ (Weiss, 2007, 261), and also TB<br />

śer(u)we ‘hunter’ if this is an inherited form (Jasanoff apud Nussbaum, 1986, 8). Here may<br />

also belong the following forms, whose etymologies will be discussed: TB ariwe* ‘ram, male<br />

goat’; TB āntse, TA es ‘shoulder’; TB yepe ‘knife’; TB yerkwanto ‘wheel’; TB yetse ‘skin’;<br />

TB yolme ‘pond, pool’; TA yṣaṃ ‘trench, moat’; TB ṣpel ‘pill’; TB sāle ‘ground, basis’, and<br />

possibly TB yerter ‘wheelrim, felloe’.<br />

On the other hand, there are lengthened grades in Tocharian nouns that do come as a<br />

surprise, e.g., TB ñem/TA ñom ‘name’ if this goes back to a protoform PIE *h 1 nḗh 3 -mn̥ . It<br />

will be argued that there is, however, no principled reason against assuming acrostatically<br />

inflected men-stems that existed beside proterokinetically inflected ones. A different case is<br />

TB yesti ‘piece of cloth’ < *u̯ ḗstoi̯ (Malzahn 2004), because it bizarrely combines ē-acrostatic<br />

root ablaut with a suffix ablaut typical of holokinetically inflected nouns.<br />

Especially in such cases, I think one should turn to Schindler’s suggestion (Schindler,<br />

1994, 398f.) that such irregular lengthened or full grades of roots found in nouns have to do<br />

with verbal Narten forms. To be sure, in my view Schindler’s original claim (“Verbalen<br />

Nartenformationen entsprechen systematisch Nominalbildungen mit analogen<br />

Ablautverhältnissen. Das läßt auf zwei ursprüngliche Wurzeltypen schließen, Standard- und<br />

Nartenwurzeln”) was much too strong and should nowadays be abandoned; on the other hand,<br />

it seems quite reasonable to assume that thanks to the principle of analogy, lengthened grades<br />

and full grades found in verbal (so-called) Narten paradigms could be transferred into<br />

respective nominal forms at least sporadically, i.e., precisely non-systematically.<br />

For Tocharian one may put forth further evidence from the root TB ñäsk- ‘to seek’<br />

(Malzahn, 2007). The same principle can be argued for TB yesti ‘piece of cloth’.<br />

Finally, I would like to argue that a weak version of Schindler’s explanation principle<br />

is a strategy to account for TB śerkw ‘cord, string’, TA nom. pl. śorkmi ‘strings’, which I<br />

think Hilmarsson has plausibly shown to derive from a pre-PT *kērg( h )-u̯ n̥ (Hilmarsson, 1986,<br />

125-144).<br />

References:<br />

Hilmarsson, Jörundur, 1986: Studies in Tocharian Phonology, Morphology and Etymology<br />

with special emphasis on the o-vocalism, Proefschrift Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden,<br />

Reykjavík.<br />

Malzahn, Melanie, 2004: “Toch. B yesti nāskoy und der Narten-Charakter der idg. Wurzel<br />

*u̯ es- ‘(Kleidung) anhaben’”, Die Sprache 43/2, 2002-2003[2004], 212-220.<br />

Malzahn, Melanie, 2007: “Tocharian Desire”, Verba Docenti. Studies in historical and Indo-<br />

European linguistics presented to Jay H. Jasanoff by students, colleagues, and friends,<br />

ed. by Alan J. Nussbaum, Ann Arbor/New York: Beech Stave Press, 237-249.<br />

25

Nikolaev, Alexander S., 2010: Issledovanija po praindoevropejskoj imennoj morfologii /<br />

Studies in Indo-European nominal morphology, Sankt-Peterburg: Nauka.<br />

Nussbaum, Alan J., 1986: Head and Horn in Indo-European, Berlin / New York: de Gruyter.<br />

Schindler, Jochem, 1994: “Alte und neue Fragen zum indogermanischen Nomen”, In<br />

honorem Holger Pedersen. Kolloquium der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft 1993 in<br />

Kopenhagen, hrsg. von Jens Elmegård Rasmussen, Wiesbaden: Reichert, 397-400.<br />

Weiss, Michael, 2007: “Latin Orbis and its Cognates”, Historische Sprachforschung 119,<br />

2006[2007], 250-272.<br />

Widmer, Paul, 1997: Nartennomen, Lizentiatsarbeit Univ. Bern.<br />

26

The accentuation of Balto-Slavic Vr̥ ddhi formations and the origin of the acute<br />

Ranko Matasović, University of Zagreb<br />

The traditional view that PIE lengthened grade vowels receive the acute in Balto-Slavic can<br />

no longer be defended. It is contradicted by such examples as PIE *d h ugh 2 tēr ‘daughter’ ><br />

Lith. duktė͂ , PIE *(H)rēk-s-o-m ‘I said’ > Croat. rijêh, PIE *h 2 ōwyom ‘egg’ > Croat. jâje. It<br />

should also be taken as proved that syllables closed by laryngeals and voiced stops (or<br />

glottalics, by Winter’s law) received the acute intonation in Balto-Slavic.<br />

However, the fact that the PIE lengthened grade long vowels are circumflex in Balto-<br />

Slavic does not prove that all lenghtened grade long vowels in Balto-Slavic are circumflex. In<br />

the present paper we shall show that a number of formations with the lengthened grade of the<br />

root, that were not inherited from PIE, received the acute in Balto-Slavic. Such words have<br />

the lengthened grade only in Balto-Slavic, but not in other IE languages, which shows that<br />

their Vr̥ ddhi is not inherited from PIE. Examples of such formations are BSl. *ślā́wā ‘fame’<br />

(Lith. šlóvė, Croat. slȁva) < PIE *k’low- (Gr. kléos), BSl. *ṓsi- ‘ash-tree’ (Lith. úosis, Croat.<br />

jȁsen) < PIE *h 3 es- (ON askr), etc. There are also cases where we cannot show that the Balto-<br />

Slavic acute occurs on a long vowel (since we find it on syllables containing diphthongs), but<br />

where derivation by Vrddhi seems plausible on semantic grounds, as well as others, where we<br />

find an unexplained acute either in Baltic or in Slavic, but not in both branches.<br />

In the present paper, we will systematically collect and analyze such material in order<br />

to show that the Balto-Slavic Vr̥ ddhi formations, in contradistinction to the inherited PIE long<br />

vowels, received the acute intonation.<br />

27

“Narten formations” versus “Narten roots”<br />

H. Craig Melchert, UCLA<br />

Verbal stems showing “acrostatic” *ḗ/é ablaut are widely labeled “Narten formations” in<br />

honor of Johanna Narten, who in 1968 first argued for the systematic existence of such a type<br />

of present: e.g. *stḗuti, *stéwn̥ ti ‘praise’ seen in Vedic astāut and Old Avestan participle<br />

stauuat-. Some scholars, most explicitly Schindler, have assumed that “Narten”-type ablaut is<br />

lexically determined: certain roots show a lengthened-grade/full-grade alternation where<br />

“normal” roots show full grade alternating with zero-grade, or full grade in a category usually<br />

showing zero grade.<br />

While certain roots do show “clusters” of lengthened-grade formations in both verbal<br />

and nominal categories, this fact per se does not justify the notion of a special class of “Narten<br />

roots”, since it is commonplace that the expected ablaut pattern of a nominal formation may<br />

be influenced by a related verbal category: e.g., beside the inherited result noun tarma- ‘peg,<br />

nail’ < *tór(h 1 )-mo- and the likely parallel karša- ‘shearing’ < *kórs-o- beside karš- ‘cut’ <<br />

*kers-, Hittite also shows for this productive formation examples like kuera- ‘field’ <<br />

*‘section’ with e-grade after kuer- ‘cut’ and gulšša- ‘fate’ with zero grade after gulšš- ‘draw,<br />

sketch’.<br />

I will argue that lengthened-grade “Narten presents” (and related secondary nominal<br />

formations) are attested in some cases to roots that also show “regular” ablaut patterns,<br />

including *h 1 es- ‘be’ (following Oettinger), *swep- ‘fall asleep’ (cf. Klingenschmitt), and<br />

others. I conclude that acrostatic “Narten presents” do not reflect a special class of roots, but<br />

are merely another among the well-established types of characterized presents. They differ<br />

merely in showing “internal” derivation rather than an overt suffix. What remains an open<br />

question is to what extent we can identify them with a particular Aktionsart.<br />

28

Root-structure and the occurrence of full and lengthened grade in PIE root nouns<br />

Benedicte Nielsen Whitehead, University of Copenhagen<br />

The paper reviews the ablaut patterns of PIE root nouns, especially the conditions for<br />

nominatival lengthening and the choice of weak grade correlating to a specific form of the<br />

nominative.<br />

Certain basics of PIE root-noun apophony are today considered commonplace, such as<br />

the link between ablaut and specific semantic types: stative agent-nouns, action nouns,<br />

nomina rei actae (Schindler 1972); or the fact that that nominatival lengthening occurs only in<br />

stems with one final consonant (e.g. Möller 1880: 499).<br />

However, Schindler 1979: 60 also pointed out that in certain well-defined cases, root<br />

structure was a determining factor for the choice of a particular ablaut grade. This paper<br />

surveys 80 root nouns of presumed IE age and qualifies his findings as follows: a root noun<br />

will only ever appear in a form that displays (a) at least one initial consonant, (b) a syllabic<br />

element and (c) if possible, exactly one final consonant. I.e., the root maintains the basic<br />

phonological structure C N V 1 C 1 , when possible.<br />

The relevance of these observations is twofold. As will be illustrated, we should,<br />

firstly, pay special attention to a small handful of root nouns that do not adhere to these rules,<br />

and secondly, we should be careful when drawing conclusions about original ablaut patterns<br />

on the basis of attested forms.<br />

These facts challenge our otherwise firm convictions about the ablaut of PIE root<br />

nouns.<br />

References:<br />

Möller, H. 1880. “Zur declination. Germanisch ā ē ō in de endungen des nomens und die<br />

Entstehung des o (*a₂)”. PBB 7: 482-547.<br />

Schindler, J. 1972. Das Wurzelnomen im Arischen und Griechischen. Dissertation: Phil. Fak.,<br />

Universität Würzburg.<br />

Schindler, J. 1979. “C. Rezension”. Die Sprache 25 (1): 57-60.<br />

29

Zu langstufigen Bildungen des Indogermanischen<br />

Norbert Oettinger, Erlangen<br />

Da die Existenz von „Narten-Wurzeln“ nicht wahrscheinlich ist, wird man mit teilweise<br />

unterschiedlicher Herkunft von in der Wurzelsilbe langstufigen Bildungen der<br />

indogermanischen Grundsprache rechnen und sie zunächst einzeln betrachten. Dies soll in<br />

jeweils kurzer Form geschehen.<br />

Beim Nomen fällt auf, dass der Typ N-A.Sg. *h 1 i̯ ēk w -r̥ , Gen. *h 1 i̯ ek w -n̥ -s ‚Leber‘ im<br />

hierarchischen Derivationssystem des Indogermanischen mit dem Typ Nom.Sg. *dóm-s, Gen.<br />

*dém-s ‚Haus‘ um die erste Position konkurriert. Auch die Langstufe mancher neutraler s-<br />

Stämme wie gr. ῥῆγος ‚Decke‘ bedarf der Diskussion.<br />

Beim Verbum scheinen manche Narten-Präsentien einmal reduplizierten Präsentien<br />

funktional gleichwertig gewesen zu sein. Dies wurde im Prinzip bereits von Harđarson (1993)<br />

vermutet. Da der spät-urindogermanische sigmatische Aorist ebenfalls Langstufe aufwies, so<br />

stellt sich die Frage, ob auch hier eine entsprechende Gleichwertigkeit vermutet werden kann.<br />

Literatur:<br />

Hackstein, Olav, 1995. Zu den sigmatischen Präsensstammbildungen des Tocharischen.<br />

Göttingen.<br />

Harđarson, Jón Axel. 1993. Studien zum Urindogermanischen Wurzelaorist und dessen<br />

Entsprechungen im Indoiranischen und Griechischen. Innsbruck.<br />

Jasanoff, Jay H. 2003. Hittite and the Indo-European Verb. Oxford.<br />

Oettinger, Norbert. 2011. Indogermanisch *h 1 es- ‘sitzen’ und luwisch asa[r]. In: MSS 65,<br />

167-170.<br />

30

‛Expressive lengthening’ – linguistic reality or strange nightmare?<br />

Oswald Panagl, Salzburg<br />

Among the representations of lengthened grade vowels reconstructed for Proto-Indo-<br />

European as well as attested in ancient Indo-European languages, most of the examples under<br />

consideration may be explained either as reflexes of laryngeals or as “Dehnstufen” (in Neo-<br />

Grammarian sense) within the traditional vowel-system. But there are also some instances<br />

which do not fit into this framework. Mayrhofer in his Indo-European Phonology (Mayrhofer<br />

1986/ 2012) mentions e.g. the word pairs *mŭs : *mūs “mouse” or *nŭ : *nū “now”: „So ist<br />

der einsilbige Nom. Sing., wohl */ṷīs/, für ‚Gift‘ im Jungavestischen noch erhalten … Wenn<br />

das ved. Verbum muṣṇā́ ti ‚stiehlt‘ primär ist und auf laryngalloses *mus-, allenfalls *meṷ-szurückweist<br />

und wenn das verbreitete Wort für ‚Maus‘ davon abgeleitet ist, dann enthält die<br />

Gleichung ved. mū́ ṣ- = lat. mūs = ahd. mūs usw. altes */ū/. Sicher alt ist */nū(n)/ … in ved. nū,<br />

gr. νῦν neben */nu/ in ved. nú, gr. νύ… etc.“ (p. 171). However, valuable observations about<br />

lengthened grade one-syllable case forms of lexemes with the vowels /i/ or /u/ are published<br />

by Specht (KZ 59, 1932, p. 280 sqq.) A special case is the particle of exclamation *ō, for<br />

which Mayrhofer denies the effect of a laryngeal.<br />

If we take into account some metrical lengthenings (Homeric āthánatos) and several<br />

irregularly long vowels unexpected so far, we may think with some scholars like Hirt (1921),<br />

Grammont (1971) of phono-stylistic reasons like emphasis, force or insistance.<br />

Do there exist phenomena comparable to spontaneous gemination of consonants? Lühr<br />

(1988) presented models and types of explanations given by Martinet (1937), who offers<br />

special semantic fields (Onomatopées, Noms d’animaux, Aliments, Parties du corps,<br />

Maladies, Métiers etc.), and Graur (1929), who emphasizes the role of „mots vulgaires“ with<br />

„une valeur affective“ and characterized by „séries d’idées susceptibles d’avoir cours dans le<br />

langage familier ou vulgaire.“ On the other hand, Wissmann (1939) underlines the dominance<br />

of lexemes in hypocoristic style (Lallwörter, Kurznamen, Tierwörter) as well as words „zur<br />

Bezeichnung von wertlosen und geringgeschätzten Dingen“.<br />

Questions upon questions!<br />

31

The lengthened grade in Tocharian nominal morphology<br />

Georges-Jean Pinault, École Pratique des Hautes Études<br />

The Tocharian phonological system does not show any contrast of length in the vowels. The<br />

reflexes of the PIE vowels *ē and *ō, as well as of the diphthongs *ēi̯ , *ōi̯ , etc. in Common<br />

Tocharian (CToch.), are still moot points, despite some advances in recent decades. In<br />

particular, the fate of these diphthongs in final position, as well as of the PIE final sequences<br />

*°ōR, *°ōN, *°ōs, etc. has been much debated. These issues are partly related to the<br />

interpretation of PIE morphology and to patterns of internal derivation. Tocharian material<br />

has been often used to confirm hypotheses about PIE issues, without due consideration of the<br />

facts that can be reconstructed for CToch. on the basis of the two daughter languages, TA and<br />

TB. The paper will propose a comprehensive survey of the traces of lengthened grade in<br />

several Tocharian nominal categories. Some problems relevant to the reconstruction of the<br />

PIE nominal inflection will also be discussed. To take a single example, it will be shown, after<br />

weighing the pros and cons, that TB ñem, TA ñom ‘name’ (CToch. *ñæmä) does not provide<br />

any evidence for the reconstruction of a lengthened grade in the inflection of the PIE noun,<br />

allegedly *h 1 nḗh 3 - for the strong stem allomorph. The still controversial reflexes in CToch. of<br />

PIE *-ōi̯ and *-oi̯ in final position will be discussed. It appears that the allomorph *-oi̯ has<br />

remained productive as making abstracts, parallel to the productivity of the abstracts in *-u̯ or<br />

> CToch. *-wær, that would have replaced *-u̯ ōr. If this argument is accepted, the Tocharian<br />

data would point to the existence of neuters with nom.-acc. sg. *-oi̯ , *-u̯ or, etc. who stand for<br />

the PIE collectives in *-ōi̯ , *-u̯ ōr as expected according to Szemerényi’s Law, from *-oi̯ -h 2 ,<br />

*-u̯ or-h 2 . The situation seems to be different for animate *-on-, *-mon- and *-u̯ on-stems,<br />

which would show in Common Toch. the reflexes of expected nom. sg. *-ōn, *-mōn and<br />

*-u̯ ōn (< *-(C)on-s).<br />

32

The Proto-Indo-European *-VTs# clusters and the formulation of Szemerényi’s Law<br />

Dariusz Piwowarczyk<br />

Szemerényi’s Law is a term used nowadays for a sound change postulated for the Indo-<br />

European proto-language through which a sequence *-V̆ Rs develops into *-V̄ Rø (1970: 109,<br />

155). Nowadays there seem to exist three different approaches to Szemerényi’s Law: some<br />

scholars assume that it operated in a way as formulated by Szemerényi himself (Neri 2003:<br />

20 35 ), others assume that it only operated in sequences consisting of a resonant and *-s<br />

(Griepentrog 1995: 177-179, Kim 2001: 127) and still other scholars deny the existence of the<br />

law altogether, assuming that the vowel was lengthened before word-final resonant (ĕR > ēR)<br />

except *-m (Beekes 1985: 151-154).<br />

In this paper I shall argue that Szemerényi’s Law operated in the proto-language and<br />

that its operation should be restricted to *-V̆ Rs# and *-V̆ RH# sequences only. The assumption<br />

of the lengthening of vowels before a resonant requires a difficult explanation of the vocative<br />

of the *r-stems (cf. Beekes 1985: 99-101) which is easily explained by assuming that the law<br />

did operate.<br />

Additionally, I will show that the development of *V̆ Ts > *V̆ ss > *V̄ s, often assumed<br />

as part of Szemerényi’s Law (cf. Neri 2003: 20 35 , Lipp 2009: 93) as in PIE *pód-s > *póss ><br />

*pṓs > Doric Greek pṓs ‘foot’ (Hesych.), is hardly credible (cf. also Kim 2001: 127 24 ).<br />

References:<br />

Beekes, Robert. 1985. The origins of the Indo-European nominal inflection. Innsbruck.<br />

Griepentrog, Wolfgang. 1995. Die Wurzelnomina des Germanischen und ihre Vorgeschichte.<br />

Innsbruck.<br />

Kim, Ronald. 2001. “Tocharian B śem ≈ Latin vēnit? Szemerenyi’s Law and *ē in PIE root<br />

aorists. MSS 61. 119-147.<br />

Lipp, Reiner. 2009. Die indogermanischen und einzelsprachlichen Palatale im<br />

Indoiranischen. Band II. Heidelberg.<br />

Neri, Sergio. 2003. I sostantivi in -u del gotico. Innsbruck.<br />

Szemerenyi, Oswald. 1970. Einfuhrung in die vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft. Darmstadt.<br />

33

Szemerényi’s law: a critical survey of the evidence<br />

Tijmen Pronk, Institut za hrvatski jezik / Leiden University<br />

Today it appears to be widely accepted that the lengthened grade vowel in the nominative<br />

singular of hysterodynamic nouns of the type *ph 2 tēr was the result of earlier loss of final *-s<br />

with compensatory lengthening of the preceding consonant, which was subsequently<br />

shortened with compensatory lengthening of the preceding vowel (Szemerényi 1999: 116).<br />

The development is generally referred to as Szemerényi’s law, although the basic idea behind<br />

it is much older (cf. Collinge 2009: 237).<br />

Nussbaum (1986: 129f.) added to Szemerényi’s hypothesis by suggesting that<br />

collectives ending in a long vowel and a resonant can be explained in a similar way. The<br />

collective ending *-h 2 would have been lost with eventual compensatory lengthening of the<br />

vowel in the preceding syllable. Szemerényi’s law has also been employed to explain a<br />

number of further isolated lengthened grades.<br />

Beekes (1990) provided several arguments against Szemerényi’s law. He argued that<br />

the asigmatic nom.sg. of the h 2 -stems proves the existence of originally asigmatic<br />

nominatives. He further argued that case endings like gen. sg. *-ei-s, *-en-s provide<br />

counterevidence against Szemerényi’s law. A similar argument applies to the thematic acc.pl.<br />

ending *-o-ns.<br />

During the lecture, the strengths and weaknesses of Szemerényi’s law will be<br />

discussed. We will also address the question whether alternative accounts of the lengthened<br />

grade may provide a better explanation for the data.<br />

References:<br />

Beekes, Robert S. P. 1990 “Wackernagel’s explanation of the lengthened grade”,<br />

Sprachwissenschaft und Philologie: Jacob Wackernagel und die Indogermanistik<br />

heute. Wiesbaden, 33–53.<br />

Collinge, N. E. 2009 The laws of Indo-European. Amsterdam–Philadelphia.<br />

Nussbaum, Alan 1986 Head and horn in Indo-European. Berlin–New York.<br />

Szemerényi, Oswald 1999 Introduction to Indo-European linguistics. Oxford.<br />

34

The derivation of Slavic imperfective verbs with lengthened grade<br />

Johannes Reinhart, University of Vienna<br />

Slavic imperfective verbs derived from verbs with a short stem vowel (e, o, ь, ъ) usually have<br />

a lengthened vowel (e.g. OCS svьtěti ‘shine’ → svitati, kloniti ‘bend’ → klanjati). According<br />

to the theory of Jerzy Kuryłowicz the lengthened grade in derived imperfective verbs started<br />

in seṭ-roots with a sonorant before the laryngeal. After the root vowel is lengthened it is<br />

introduced to the position before a vowel, e.g. trh 1 -tei ‘rub’ > tīrh 1 -tei, tīrh 1 -ā-tei > tĭrh 1 -tei,<br />

tīrh 1 -ā-tei. Then the preconsonantal vowel is shortened and can be recognized only by its<br />

accentuation. This is the origin of the apophonic relationship of verbs of the tĭrti (OCS trьti) ~<br />

-tirati type. This relationship was later analogically spread to verbs like bĭrati ~ -birati, merti<br />

~ -mirati and gnesti ~ -gnětati, greti ~ -grěbati.<br />

There are, however, some insurmountable difficulties related to Kuryłowicz’s theory.<br />

One such difficulty is that the shortening of preconsonantal long-vowels in the structure ī/ūRC<br />

must have taken place not long after the development of short high-vowels in front of syllabic<br />

sonorants, which is dated no later than 1000 BC. On the other hand, the origin of Common<br />

Slavic verbal aspect is a relatively recent process, cf. e.g. van Wijk: „Le système des aspects<br />

est lui aussi d’origine relativement moderne“ (RÉSl 9, 1929: 251).<br />

One must also bear in mind that imperfective verbs of the type -tirati are always found<br />

with verbal prefixes and have the following derivational history: simple verb (e.g. tьrti) →<br />

prefix + simple verb (prětьrti) → prefix + derived imperfective verb (prětirati). Therefore<br />

simple verbs in the modern languages (e.g. Sln. tirati) probably owe their existence to the loss<br />

of the prefix (dépréverbation). This means that in the framework of Kuryłowicz’s theory<br />

simple derived imperfective verbs existed for several centuries only to disappear before the<br />

earliest written texts. These facts force us to abandon Kuryłowicz’s theory as a general<br />

principle and to look for alternative solutions.<br />

In this paper an attempt is made to explain the lengthened grade in Slavic imperfective<br />

derivation as the result of different processes. The following processes come into<br />

consideration: (a) denominative verbs derived from nouns with a long vowel (some of which<br />

might be explained by Kuryłowicz’s formula); (b) derived verbs with lengthened grade (of IE<br />

origin or post-IE formations built after IE models); (c) after a proportion Te/aRT : TuRT =<br />

Te/aHT : x, x = *TuHT (= TūT) etc. (cf. Mathiassen, Studien, 1974: 18); (d) by the<br />

relationship ī : ĭ (i : ь; < *ei : i) arisen after the monophtongisation of diphthongs.<br />

If the scenario suggested in this paper is true, then the derivation of Slavic<br />

imperfective verbs with lengthened grade is a typical case of a conspiracy.<br />

35

On the Phonetics and Phonology of Stang's and Szemerényi's Laws<br />

Ryan Sandell, UCLA<br />

This paper works towards a better understanding of the phonetic and phonological processes<br />

in Proto-Indo-European that bear the labels of Stang’s Law (Stang 1965: 292 ff.) and<br />

Szemerényi’s Law (Szemerényi 1970: 106-11). Descriptively, both laws appear to involve the<br />

the loss of certain consonants in auslaut when preceded by certain other consonants, with<br />

consequent compensatory lengthening of the vowel in the final syllable (e.g., **di̯ eu̯ -m ><br />

*di̯ ēm; **ph 2 ter-s > *ph 2 tēr). Principally, two questions require an account:<br />

1. why are those certain word-final consonants lost?<br />

2. why does the loss of those consonants result in compensatory lengthening?<br />

Answers to the first question seem largely straightforward with respect to Stang's Law:<br />

assimilation of segments, coupled with the well-known constraint against adjacent identical<br />

segments in PIE, leads to loss of a consonant (cf. Mayrhofer 1986 [2012]: 171-2). In the case<br />

of Szemerényi's Law, already Szemerényi (1970: 109) advanced a similar explanation based<br />

on assimilation (e.g., *-rs#>*-rr#) and degemination, but some more recent work (e.g., Byrd<br />

2010: 88-94) has instead suggested that a general ban on word-final resonant + fricative<br />

sequences was operative in PIE. The fact that cases involving both *s and *h 2 , despite the<br />

divergent phonetic properties of those segments, have been adduced as instances of<br />

Szemerényi's Law (cf. Szemerényi 1970: 155, 159), raises the further question of whether the<br />

all Szemerényi's Law phenomena reflect the same process.<br />

The second question is more troubling, in light of the fact that a plausible model of<br />

compensatory lengthening (Moraic Theory; see Hayes 1989) does not predict compensatory<br />

lengthening of the type VC 1 C 2 # > V̄ C 1 #, and that the typological study of Kavitskaya (2002)<br />

does not find evidence for compensatory lengthening of such a type. Evidence from Greek,<br />

Latin, and Indo-Iranian, however, suggests that word-final consonants may have been<br />

extrametrical (i.e., did not bear a mora) in PIE (a not uncommon situation cross-linguistically;<br />

cf. Hayes 1995: 56-60). Thus, when a formerly weight-bearing consonant became word-final,<br />

its mora was transferred to the preceding vowel, and so produced the lengthened vowel.<br />

References:<br />

Byrd, A. M. (2010). Reconstructing Indo-European Syllabification. Ph.D. thesis, University<br />

of California, Los Angeles.<br />

Hayes, B. (1989). Compensatory Lengthening in Moraic Phonology. Linguistic Inquiry 20,<br />

253--306.<br />

Hayes, B. (1995). Metrical Stress Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.<br />

Kavitskaya, D. (2002). Compensatory Lengthening: Phonetics, Phonology, Diachrony. New<br />

York: Routledge.<br />

Mayrhofer, M. (1986 [2012]). Indogermanische Grammatik I 2: Lautlehre. Heidelberg: Carl<br />

Winter.<br />

Stang, C. (1965). Indo-Européen *G w ŌM, *D(I)I̯ ĒM. In: Symbolae linguisticae in honorem<br />

Georgii Kuryłowicz (Polska Akademia Nauk. Prace Komisji Językoznawsta, ed.).<br />

Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.<br />

Szemerényi, O. (1970). Einführung in die vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft. Darmstadt:<br />

Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.<br />

36

The fourth makes it whole? The reduced lengthened ablaut grade in Old Indo-Aryan<br />

Ondřej Šefčík, Masaryk University, Brno<br />

Due to the abolishing of both original IE o-grades (i.e. IE full o-grade and lengthened o-<br />

grade) in Indo-Iranian, the ablaut system of Indo-Aryan was formed with only three grades:<br />

reduced (RG, 0/i), full (FG, a) and lengthened (LG, ā).<br />

We can describe the ablaut system in OIA with a set of values distinguishing different<br />

grades, i.e. any given ablaut grade is attached to a unique set of values.<br />

For describing the Old Indo-Aryan ablaut system, we need only four values of two<br />

features ({±reduced} and {±lengthened}) thus FG = {-reduced, -lengthened}, RG: =<br />

{+reduced, -lengthened}; LG = {-reduced, +lengthened}:<br />

0/I RG<br />

=<br />

a ā FG LG<br />

This system is not “complete”, since there is a gap where there could be a grade with<br />

values {+reduced, +lengthened}. It should be noted that this gap was filled in the Balto-Slavic<br />

languages, which have two reduced lengthened grades in two variants: {e-reduced<br />

lengthened} and {o-reduced lengthened}.<br />

We suppose that analogically in Old Indo-Aryan, there are traces of tendencies to<br />

formalize a fourth grade (i.e. reduced lengthened grade, RLG, ī) and we can at least partially<br />

reach the “complete” system of ablaut in OIA as:<br />

0/i (ī) RG (RLG)<br />

=<br />

a ā FG LG<br />

The forming of “reduced lengthened” grade in OIA was seconded by the fact, that the<br />

loss of original laryngeals left roots lengthened, when those roots, unlike roots which lack an<br />

original laryngeal. Thus lengthened reduced grade arose first as a variant of reduced grade.<br />

For a further systematization of the RLG we should note the following tendencies:<br />

1. In the passive of the present stem (ya-passive), with the lengthening of a preceding<br />

root vowel of otherwise non-lengthened reduced grade.<br />

2. Analogically, in the formation of the derivative stem.<br />

3. In the reduplicative aorist, where the reduplication syllable is “reduced” like the<br />

reduplication syllables of present or desiderative reduplication, but is also<br />

“lengthened”, either by the quality of the reduplication vowel or position.<br />

It is no coincidence that all three stems are “secondary”, i.e. highly productive stems<br />

with a clear semantics (passive, desiderative, causative aorist), which contrast with old<br />

37

“primary” stems. The first two stems arose from positional lengthening before a lost laryngeal<br />

as well, while the third was probably formed independently purely through an analogy.<br />

Selected literature:<br />

Kortlandt, F. H. H. (1972) Modelling the Phoneme - New Trends in East European<br />

Phonemic Theory. The Hague: Mouton.<br />

MacDonell, A. A. (1910): Vedic Grammar. Strassburg: Karl J. Trübner.<br />

Marcus, S. (1967) Introduction mathématique à la linguistique structurale. Paris: Dunod.<br />

Šefčík, O. (2008) Values, Features, Fine Metrics and Oppositions. Linguistica Brunensia 56:<br />

5–14.<br />

Šefčík, O. (2009) Preliminary Description of the Czech Phonemic System Using Feature<br />

Geometry. In: Dočekal, M. & M. Ziková (eds.) Czech in Formal Grammar 183-196.<br />

Muenchen: Lincom Europa.<br />

Whitney, W. D. (1885): The Roots, Verb-forms and Primary Derivatives of the Sanskrit-<br />

Language. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel.<br />

Whitney, W. D. (1924 5 ): Sanskrit Grammar. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel.<br />

38

Zur Etymologie von griechisch κῆλᾰ ‚Pfeile, Geschosse‘<br />

Thomas Steer, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg<br />

Die Etymologie von gr. Nom.-Akk.Pl.n. κῆλᾰ ‚Pfeile, Geschosse‘ (Il.+) ist noch nicht<br />

abschließend geklärt. Formal und semantisch bestehen verschiedene Anschlussmöglichkeiten,<br />

vgl. z.B. R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek (Leiden / Boston 2010) s.v.<br />

Die Belegstellen bei Homer, wo κῆλᾰ in erster Linie die Geschosse des Pfeilgottes<br />

Apollon bezeichnet, machen eine ursprüngliche Bedeutung ‚Pfeile‘ wahrscheinlich. Daher<br />

dürfte die bereits mehrfach vorgeschlagene und favorisierte Verknüpfung von κῆλᾰ mit ved.<br />

śará- ‚Rohr‘ (RV+), ‚Pfeil‘ (AV+), śáru- ‚Geschoss, Pfeil, Speer‘ (RV+) semantisch am<br />

wahrscheinlichsten sein. Hinzu kommen noch andere Argumente: Bei Homer werden mit<br />

κῆλᾰ nur Geschosse von Göttern (A 53 des Apollon, M 280 des Zeus) bezeichnet. Und auch<br />

im Rigveda wird śáru- offenbar nur für von Göttern gesandte Geschosse benutzt. Außerdem<br />

bestehen zwischen Apollon und dem altindischen Gott Rudra, der auch Śarva (abgeleitet von<br />

śáru-) genannt wird (vgl. VS 16,18; 16,28), sehr auffällige mythologische Parallelen (Pfeil<br />

und Bogen als Attribute; Seuchen- und Heilgötter etc.); vgl. z.B. Th. Oberlies, Die Religion<br />

des R̥ gveda. Erster Teil: Das religiöse System des R̥ gveda (Wien 1998) 206f., 213–16.<br />

Als lautlich problematisch bei der semantisch und mythologisch gut motivierten<br />