Management of pregnancy - VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines ...

Management of pregnancy - VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines ...

Management of pregnancy - VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>VA</strong>/<strong>DoD</strong> <strong>Clinical</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> Guideline<br />

For Pregnancy <strong>Management</strong><br />

The American Cancer Society (ACS) (Saslow, 2002) recommends routine cervical screening for sexually active<br />

women between the ages <strong>of</strong> 21 and 70. Furthermore, ACS recommends cervical screening be performed annually<br />

with conventional cervical cytology smears or every two years using liquid-based cytology. Women over age 30<br />

who have had three consecutive, technically satisfactory normal/negative cytology results may be screened every<br />

two to three years (unless they have a history <strong>of</strong> in utero diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure, are HIV positive, or are<br />

immunocompromised by organ transplantation, chemotherapy, or chronic corticosteroid treatment) (Saslow et al.,<br />

2002).<br />

The United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) strongly recommends screening for cervical cancer<br />

in women who have been sexually active and have a cervix. Indirect evidence suggests most <strong>of</strong> the benefit can be<br />

obtained by beginning screening within three years <strong>of</strong> onset <strong>of</strong> sexual activity or age 21 (whichever comes first) and<br />

screening at least every three years (USPSTF, 2003). All pregnant women are included in this population, and<br />

recommendations for screening apply during this time in their lives. There is no evidence <strong>of</strong> an increased incidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> cervical dysplasia during <strong>pregnancy</strong> that would necessitate more frequent testing (Lurain & Gallop, 1979). This<br />

fact, combined with increased rates <strong>of</strong> false positive cervical cytology in <strong>pregnancy</strong>, challenges the common practice<br />

<strong>of</strong> uniformly performing cervical smears at the first antenatal visit.<br />

The goal in evaluating abnormal cervical cytology is to rule out the presence <strong>of</strong> invasive cervical cancer (LaPolla et<br />

al., 1988). Colposcopy is safe during <strong>pregnancy</strong>, but should be performed only by colposcopists experienced in<br />

<strong>pregnancy</strong> exams (Wright et al., 2007).<br />

The use <strong>of</strong> cytobrush and spatula may cause minimal spotting in <strong>pregnancy</strong>, but is not associated with any adverse<br />

outcomes (H<strong>of</strong>fman et al., 1991; Koonings et al., 1992). The endocervical swab is less sensitive than a brush for<br />

endocervical sampling and should therefore not be used (Martin-Hirsch et al., 1999).<br />

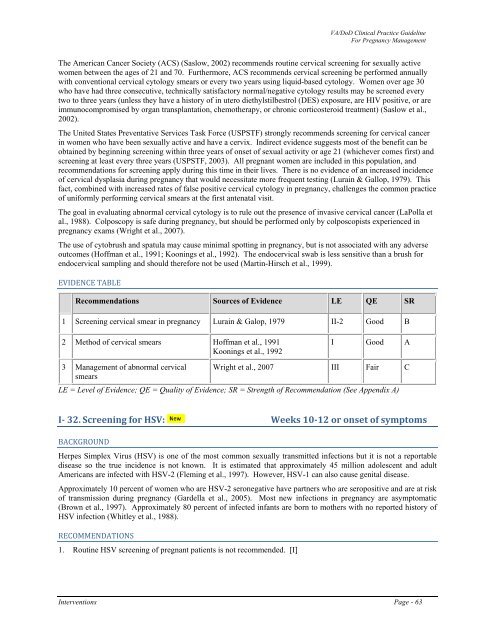

EVIDENCE TABLE<br />

Recommendations Sources <strong>of</strong> Evidence LE QE SR<br />

1 Screening cervical smear in <strong>pregnancy</strong> Lurain & Galop, 1979 II-2 Good B<br />

2 Method <strong>of</strong> cervical smears H<strong>of</strong>fman et al., 1991<br />

Koonings et al., 1992<br />

I Good A<br />

3 <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> abnormal cervical Wright et al., 2007 III Fair C<br />

smears<br />

LE = Level <strong>of</strong> Evidence; QE = Quality <strong>of</strong> Evidence; SR = Strength <strong>of</strong> Recommendation (See Appendix A)<br />

I 32. Screening for HSV: Weeks 1012 or onset <strong>of</strong> symptoms<br />

BACKGROUND<br />

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) is one <strong>of</strong> the most common sexually transmitted infections but it is not a reportable<br />

disease so the true incidence is not known. It is estimated that approximately 45 million adolescent and adult<br />

Americans are infected with HSV-2 (Fleming et al., 1997). However, HSV-1 can also cause genital disease.<br />

Approximately 10 percent <strong>of</strong> women who are HSV-2 seronegative have partners who are seropositive and are at risk<br />

<strong>of</strong> transmission during <strong>pregnancy</strong> (Gardella et al., 2005). Most new infections in <strong>pregnancy</strong> are asymptomatic<br />

(Brown et al., 1997). Approximately 80 percent <strong>of</strong> infected infants are born to mothers with no reported history <strong>of</strong><br />

HSV infection (Whitley et al., 1988).<br />

RECOMMENDATIONS<br />

1. Routine HSV screening <strong>of</strong> pregnant patients is not recommended. [I]<br />

Interventions Page - 63