Queensland Art Gallery - Queensland Government

Queensland Art Gallery - Queensland Government

Queensland Art Gallery - Queensland Government

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

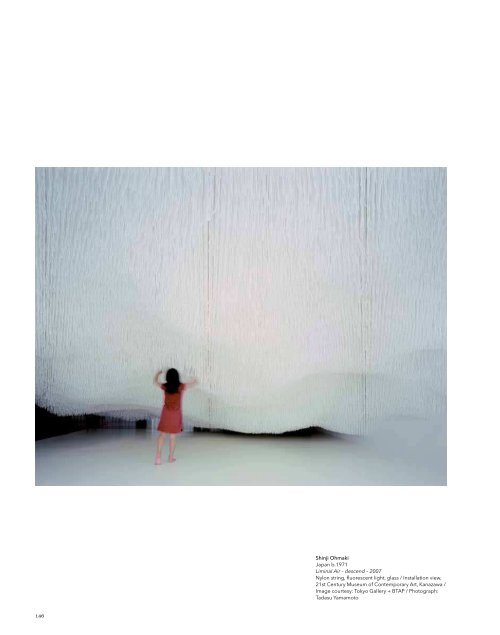

Shinji Ohmaki<br />

Dissolving into light<br />

It is often said that artists ‘transform spaces’, yet their approaches<br />

vary greatly. The works of Shinji Ohmaki transform space, but not by<br />

assimilation; rather, by dissimilation. 1 Aristotle wrote that ‘<strong>Art</strong> imitates<br />

nature’; Ohmaki’s works neither imitate nature nor try to be natural.<br />

Instead, they make us recognise that we, as human beings, are ‘others’,<br />

existing outside the natural laws of space.<br />

I remember the first time I walked into Ohmaki’s 2002 installation<br />

ECHO. I felt a sense of dislocation as the bright flowers drawn with<br />

food colouring on the floor began to blur and disintegrate from the<br />

impact of my own footsteps, and were left as a stain on the floor. I was<br />

the one who destroyed the beauty of the work.<br />

Works that encourage audience participation, and require viewers<br />

to complete them, tend to be united under the banner of ‘relational’<br />

or ‘interactive’ art. In the case of ECHO, however, the installation<br />

dissimilates us, making us aware that the beauty of the flowers<br />

is artificial on several levels. It is created by human hands and,<br />

furthermore, drawn in artificial food colouring, the result of human<br />

desire to make natural colours and flavours more intense. It is the<br />

viewer who collapses this artificiality.<br />

According to the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, flowers and<br />

plants are not intended to be beautiful; it is nature’s rationality that<br />

gives them beauty. However, beauty created by people is motivated<br />

by a desire that Kant called ‘purpose’. 2 At first glance, Ohmaki’s<br />

works often appear seductive and serene, perhaps because of their<br />

accessibility and use of appealing motifs, such as flowers, soap<br />

bubbles and light. On the other hand, the works gently point out<br />

that human life and energy motivated by desire or ‘purpose’ can<br />

sometimes be violently transformed — and this transformation may<br />

not always be welcome.<br />

anime film Akira, in which the lead character’s spirit becomes fused<br />

with his body, which dissolves into light and then transforms into energy.<br />

The white ropes and white light surround viewers in the glass space,<br />

merging them into the glowing installation like the character in the<br />

film. Liminal Air – descend – 2007–09 is a work inviting an experience of<br />

dissolution, in which we become fused with our environment.<br />

In Ohmaki’s most recent installation, Vacuum Fluctuation 2009, shown<br />

at Tokyo Wonder Site Shibuya, the dregs of consumer society —<br />

represented by tonnes of industrial slag — gradually fell to the floor<br />

from a small hole in the ceiling during the course of the exhibition.<br />

Like a grisly hourglass, the work registered how human beings are<br />

consuming the earth’s energy and rapidly destroying its environment.<br />

Shinji Ohmaki’s practice is beautiful. The seductiveness and serenity<br />

of his work may perhaps overshadow the fact that his practice also<br />

works as a warning to contemporary society. Human beings are a part<br />

of nature, but will be dissimilated easily, as Ohmaki’s work tells us, if we<br />

do not pay it enough attention. Yet Ohmaki never becomes cynical. He<br />

maintains hopes and dreams, and tries to encourage us to coexist with<br />

our natural environment — by communicating through art.<br />

Shihoko Iida<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 ‘Dissimilation’ means to become dissimilar or less similar to one’s environment. In<br />

this essay, the word means that a viewer becomes alien in the installation space by<br />

invading and destroying its spatial harmony, and comes to realise his/her isolated<br />

existence in the environment.<br />

2 See Immanuel Kant, The Critique of Judgement, 1790, trans. Shinoda, Hideo,<br />

Iwanami Shoten, Japan, 1964.<br />

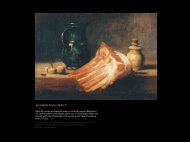

Shinji Ohmaki<br />

Japan b.1971<br />

Liminal Air – descend – 2007<br />

Nylon string, fluorescent light, glass / Installation view,<br />

21st Century Museum of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>, Kanazawa /<br />

Image courtesy: Tokyo <strong>Gallery</strong> + BTAP / Photograph:<br />

Tadasu Yamamoto<br />

Still, Ohmaki does not place us in a double bind; rather, his works offer<br />

multifarious viewpoints, particularly in his ‘Liminal Air’ series started<br />

in 2003. These massive installations invite us to experience multiple<br />

ideas of ‘liminality’, including the reversal of inside and outside, the<br />

visible and invisible, body and spirit, and life and death. In 2003,<br />

Ohmaki played with physiological and spatial liminality, covering the<br />

entire ceiling of the Tokyo Wonder Site Hongo gallery space with a<br />

large cascade-like structure made of plaster, which reached down<br />

to the floor. Later that year, at <strong>Gallery</strong> A4 (A-quad) in Tokyo, Ohmaki<br />

constructed a new version of the work by suspending approximately<br />

120 000 braided nylon ropes from the ceiling. In 2007, at the 21st<br />

Century Museum of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>, Kanazawa, this work was<br />

developed further to create Liminal Air – descend – 2007. Here, Ohmaki<br />

hung approximately 120 000 braided nylon ropes from the ceiling in<br />

a specially constructed glass space filled with subdued lighting. The<br />

work crystallised a concept he drew from a scene in the 1988 Japanese<br />

146 147