Queensland Art Gallery - Queensland Government

Queensland Art Gallery - Queensland Government

Queensland Art Gallery - Queensland Government

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

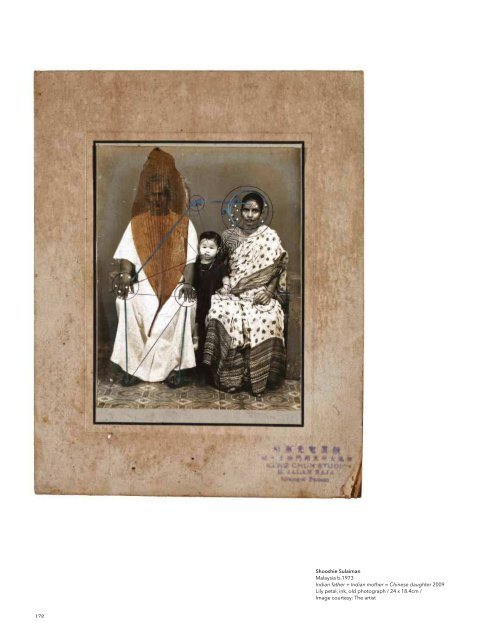

Shooshie Sulaiman<br />

Who’s afraid of the dark?<br />

My father, of Scottish heritage, is a great storyteller, and I have many<br />

eloquent memories of him telling stories about his life. My parents<br />

have always been very open and no question was taboo in our<br />

household. There was, however, one question I never posed — about<br />

my mother’s life in Malaysia. She was born in Malaysia to Chinese<br />

parents and came to Australia to attend university in the 1970s, but all<br />

other details are shrouded in darkness.<br />

I was the only child with Chinese heritage at my small primary school<br />

in far north <strong>Queensland</strong>. Apart from my mother’s face, the faces on<br />

the nightly news were the only representations of Chinese and Malay<br />

people that I was familiar with. Many years later, I still feel a sense of<br />

the unfamiliar while viewing Shooshie Sulaiman’s Darkroom 2009, an<br />

installation of photographic portraits of men and women from around<br />

Malaysia, posed alone, in pairs and in groups.<br />

Sulaiman found these portraits of nameless people in second-hand<br />

stores around Malacca. The portraits, dating from the 1950s and 1960s<br />

with their sepia tones, reference the time preceding the 13 May 1969<br />

race riots. 1 Sulaiman was born after the riots, but lives with their legacy as<br />

a person of both Malay and Chinese heritage. In Darkroom, she brings<br />

together approximately 50 portraits, transforming the faces of the portrait<br />

sitters using flower petals, collage, ink and paint, and mounting the<br />

images in found frames. The petals of pressed lily, lotus, poppy, tulip and,<br />

particularly, the hibiscus are used to soften the faces of the male figures.<br />

Hibiscus rosa-sinensis is the national flower of Malaysia, although<br />

it is not native to the country. Its five petals represent the nation’s<br />

five principles: belief in God, loyalty to king and country, upholding<br />

the constitution, the sovereignty of the law, and good behaviour<br />

and morality. These were first announced at Independence Day<br />

celebrations in 1970 in response to the events of 1969. Sulaiman’s use<br />

of single hibiscus petals in Darkroom is thus a subtle device through<br />

which she questions Malaysia’s national principles and laws.<br />

people. Single group photographs tend to display a false sense of<br />

unity; although the family is all smiles, many other frames reveal frowns<br />

and tensions. Portraits of a nation also tend towards a false sense<br />

of unity. The Malaysian <strong>Government</strong> describes the nation as a place<br />

where ‘Malays, Chinese, Indians and many other ethnic groups . . . have<br />

influenced each other, creating a truly Malaysian culture’. 2 It may be<br />

argued that Darkroom, as a collection of nameless faces, is better able<br />

to display the diversity and multiplicity of stories — as well as hint at the<br />

lost ones — that create the Malaysian national portrait.<br />

The portraits of these nameless faces are installed in an ‘open house’, a<br />

replication of the library in Sulaiman’s former Kuala Lumpur residence,<br />

a small wooden building behind the National <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> and the<br />

National Theatre — two of Malaysia’s major art institutions. The ‘open<br />

house’ is an ongoing metaphor in Sulaiman’s work — she makes herself<br />

and her work accessible via open spaces. She opens her home for art<br />

exhibitions, in keeping with the Malaysian festive tradition of opening<br />

your home to family, friends and strangers to celebrate cultural or<br />

religious festivities. For Darkroom, Sulaiman opens the doors of her<br />

library to us, inviting us to join her in celebrating the ambiguous and<br />

fractured nature of Malaysian identity.<br />

Ellie Buttrose<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 On 13 May 1969, following the 10 May Malaysian general election, Chinese–Malay<br />

race riots broke out in Kuala Lumpur. A state of emergency was declared, and there<br />

were officially around 200 deaths, although unofficial figures are far greater.<br />

2 Tourism Malaysia, <br />

viewed October 2009.<br />

Shooshie Sulaiman<br />

Malaysia b.1973<br />

Indian father + Indian mother = Chinese daughter 2009<br />

Lily petal, ink, old photograph / 24 x 18.4cm /<br />

Image courtesy: The artist<br />

Women are chronically under-represented in some aspects of Malaysian<br />

society, especially in politics, where they make up only ten per cent of<br />

parliament. Sulaiman counters this by using flower petals to soften the<br />

dominant representation of men, and brings women’s issues to the<br />

surface by painting over the women’s portraits with red ink, with titles<br />

like ‘menstruation’. Sulaiman is also interested in the slippage that occurs<br />

in the process of trying to define genders, which, like race, dominates<br />

identity politics. She creates ambiguity by partially covering female<br />

portraits with paper laden with text and titling them ‘masculine’, and<br />

using flower petals as a mechanism for feminising the male portraits.<br />

My parents, sister and I have very rarely been captured in the same<br />

frame. Our collection of photographs of us in pairs or trios is better<br />

able to represent my family as a group of related but independent<br />

172 173