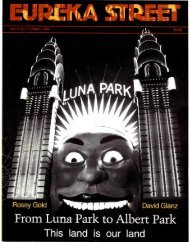

0 - Eureka Street

0 - Eureka Street

0 - Eureka Street

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Lucy Turner<br />

Guatemala's unforgiven<br />

As the government apologises to victims' families for state-sanctioned atrocities during the civil war,<br />

the perpetrators remain free<br />

BY BAM oN a<br />

AuGu" 2005, the<br />

Sacapulas Municipal Hall is filled with<br />

residents of surrounding villages, dressed<br />

in traditional traje and speaking quietly<br />

in Qu iche, the local indigenous language.<br />

Representatives of the Guatemalan government,<br />

weary from the five- hour drive<br />

to the sma ll highland town, and looking<br />

uncomfortable in their stiff suits, begin to<br />

take their seats on the stage. Despite the<br />

heat and the crowd, in the early light the<br />

hall has the reverent hush of a chapel.<br />

Domingo, Agustin and Ju an sit silently<br />

in the first row, their faces revealing a sadness<br />

which the events about to take place<br />

will do little to ease. They are preparing to<br />

hear government officials publicly accept<br />

state responsibility for the 1990 murder<br />

of their m other, Maria Mejia, a respected<br />

community leader and outspoken critic<br />

of the arm y. They will offer formal apologies,<br />

and seek her family's forgiveness.<br />

The banner su spended above the officials'<br />

heads, bearing a photo of Maria<br />

and printed with stark black lettering,<br />

expresses succinctly the response they<br />

can expect: No hay perd6n sin justicia<br />

No forgiveness without justice.<br />

Fifteen years after her brut a 1 assassination<br />

in front of her husband and children<br />

by members of the military who still live<br />

in their village, no investiga tions have<br />

taken place, no one has been charged, and<br />

the case remains, like thousands like it,<br />

in absolute impunity.<br />

Guatemala is still coming to terms<br />

with peace a decade after a 36-year civil<br />

war ended with the signing of peace<br />

accords. Among the challenges it faces<br />

is how to address the profound dam age<br />

caused by decades of conflict and state<br />

repression, which included atrocities such<br />

as the massacre of hundreds of indigenous<br />

villages, tens of thousands of 'disappearances'<br />

and widespread torture.<br />

As in other countries undergoing<br />

post-conflict transitions, Guatemala<br />

established a truth commission as part<br />

of its reconciliation process. In 1999, the<br />

H istorical Clarification Commission<br />

(CEH, for its initials in Spanish) published<br />

its report, Guatemala-Memory of<br />

Silence, which concluded that the civil<br />

war had claimed more than 200,000<br />

victims, 83 per cent of whom were<br />

indigenous Mayans. The report found that<br />

the state was responsible for 93 per cent of<br />

the human rights violations committed,<br />

which included genocide.<br />

The CEH 's recommendations, in<br />

addition to stressing the importance of<br />

the peace accords, sought to specifically<br />

address victims' needs. These recommendations<br />

included m easures for dignifying<br />

the memory of victims, a wide-rangi ng<br />

reparations program, and, importantly,<br />

justice.<br />

0<br />

VER THE PAST S I X YEARS Guatemalan<br />

governments have implemented some<br />

of these recommendations, most notably<br />

via the creation of a N ational Reparation<br />

Program, which includes material restitution<br />

(such as building roads), economic<br />

compensation, psychological rehabilitation,<br />

and measures to dignify victim s<br />

(such as monuments and the renaming<br />

of buildings). Little has been done, however,<br />

to bring those responsible for human<br />

rights crimes to justice.<br />

In contrast to other societies undergoing<br />

post-conflict tran sitions, Guatemala<br />

did not pass sweeping amnesty laws as<br />

part of its reconciliation process.<br />

The 1996 National Reconciliation Law,<br />

which provides for the limited exemption<br />

of responsibility in some cases, specifically<br />

excludes crimes against humanity-in particular<br />

genocide, forced disappearance and<br />

torture-committed during the internal<br />

armed conflict. The CEH recommended<br />

that those responsible for such crimes be<br />

prosecuted, tried and punished.<br />

This means there is no legal barrier to<br />

proceeding against human rights violators.<br />

On the contrary, the government has strong<br />

political,lega land moral obligations to bring<br />

those responsible to justice. Politically, it<br />

committed itself to fight impunity in the<br />

Global Agreement on Human Rights, one<br />

of the principal peace accords signed in<br />

1994. In addition, the nation's constitution<br />

and a range of international human rights<br />

treaties impose a legal duty to investigate,<br />

try, and punish human rights violators.<br />

The moral imperative is confirmed by<br />

the proliferation of victims' organisations<br />

since the signing of the peace accords and<br />

their persistent demand that justice is the<br />

only path to real reconciliation.<br />

Despite this, impun ity remains a fact<br />

for almost 100 per cent of human rights<br />

abuses committed during Guatemala's<br />

civil war.<br />

There are many reasons for this,<br />

the primary one being a lack of political<br />

will: the political spectrum remain s<br />

dominated by right-wing parties whose<br />

m embers and supporters among the armed<br />

forces m ight well be the focus of criminal<br />

investiga tions.<br />

Lack of political will is compounded<br />

by the systemic weaknesses of the justice<br />

system. The institutions responsible<br />

for carrying out criminal investigations<br />

arc under-resourced, staffed by inadequately<br />

trained and inadequately experienced<br />

personnel, and show little interest<br />

in initiating the investigations as they are<br />

required to do by law. The court system<br />

is renowned for its inefficiency, inconsistency<br />

a nd corruption.<br />

Furthermore, the Ministry of Defense<br />

is unco-operative with criminal investigations<br />

indicating military involvement<br />

in human rights crimes. It has classified<br />

much of the information held by the armed<br />

forces as 'state secrets', in order to prevent<br />

its release. When cases do come to trial,<br />

the army defends its own by paying lawyers<br />

who employ obstructionist legal tactics<br />

aimed at delaying proceedings and<br />

exhausting victims' resolve.<br />

In light of these obstacles, only a handful<br />

of cases have been adequately investigated<br />

and tried, and even fewer have resulted in<br />

appropriate sanctions being imposed. These<br />

18 EUREKA STREET NOVEMBER- DECEMBER 2005