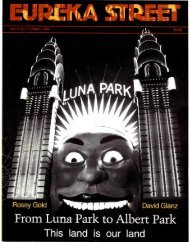

0 - Eureka Street

0 - Eureka Street

0 - Eureka Street

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Brian F. McCoy<br />

Tired of the injustice<br />

Fifty years ago Rosa Parks inspired African Americans by refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man,<br />

and her example is still inspiring Aboriginal people today<br />

0 N<br />

' D cccMBU '955, a Thu"day<br />

night in Montgom ery, Alabama, Rosa<br />

Parks, 42, boarded a bus to head home.<br />

It had been a long h ard day and she<br />

was tired. She and three other African<br />

Americans sat in the fifth row, the farthest<br />

forward they were allowed. After a<br />

few stops the first four rows were fi lled<br />

with whites and a white man was still<br />

standing. By law in Alabama black and<br />

white could not share the sa me row. The<br />

other three stood. She refused.<br />

The bus driver threatened to call the<br />

police. Everyone else stood up except her.<br />

'Go ahead and call them,' she said, 'I'm<br />

not moving.' The police came; she was<br />

arrested and later charged. This was not<br />

the fi rst time an African American had<br />

protested against racial discrimination or<br />

refused to give up their scat on a public<br />

bus. But this time was to prove different.<br />

Rosa was a committed Christian<br />

who belonged to the African Methodist<br />

Episcopal Church. She had worked with<br />

Dexter Nixon, secretary of the National<br />

Association for the Advancement of<br />

Colored People, and enjoyed considerable<br />

respect in her own community.<br />

When she later said, 'Our mistreatment<br />

was just not right, and I was tired<br />

of it,' she gave voice to a feeling many<br />

others could share. This time, facing a<br />

driver who had refused her once before<br />

because she would not enter the bus by<br />

the rear door, she realised she had taken<br />

an important step. She was found guilty<br />

and fi n ed $14.<br />

Her charge, violating a city segregation<br />

code, provided the opportunity for a legal<br />

test case in the United States Supreme<br />

Court. However, the result of that challenge<br />

rem ained more than a year away.<br />

Her arrest touched and encouraged others<br />

to act, and within three days a boycott of<br />

Montgomery buses h ad been called. On<br />

the evening before the boycott, a you ng<br />

Baptist minister stood up and spoke to a<br />

large assembled church gathering. 'There<br />

com es a time,' he reminded them, 'when<br />

people get tired.' He added: 'We are tired<br />

of being segregated and humiliated; tired<br />

of being kicked about by the brutal feet of<br />

oppression.' The speaker was 26-ycar-old<br />

M artin Luther King. Ordained a Baptist<br />

minister at 19, Nobel Peace Prize recipient<br />

at 35, assassinated at 39.<br />

Later that night the enormity of the<br />

challenge was revealed. Any protest, the<br />

assembled group realised, would need to<br />

stand up against the violence that continued<br />

to be expressed by white people and<br />

institutions towards them . And, as if that<br />

wasn't enough to contend with, the protesters<br />

also h ad to consider possible retaliation<br />

by their own people. In many cases<br />

they were the ones most directly affected<br />

by the hardship of a bus boycott.<br />

As the imminent danger and risks<br />

dawned upon them , King would la tcr recall,<br />

'The clock on the wall read almost midnight,<br />

but the clock in our souls revealed<br />

that it was daybreak.' Whatever his oratory<br />

that night, and whatever the skills a nd<br />

energy others brought to that meeting, it<br />

was Rosa Parks who provided the mom ent<br />

others could identify with and support.<br />

She was not the only one who was tired.<br />

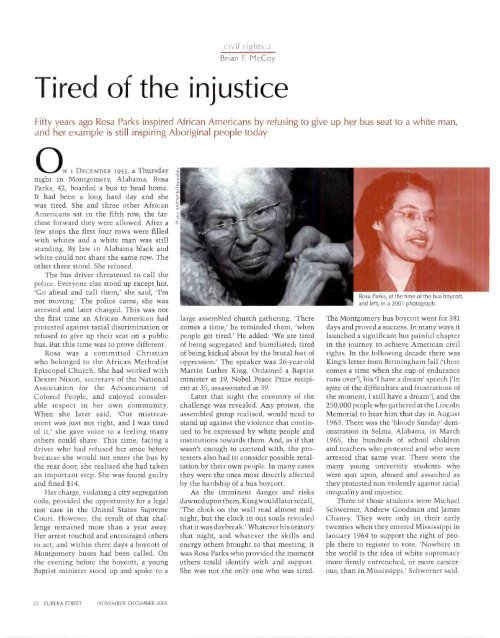

Rosa Parks, at th e time of th e bus boycott,<br />

and left, in a 2001 photograph.<br />

The Montgom ery bus boycott went for 381<br />

days and proved a success. In many ways it<br />

launched a significant but painful chapter<br />

in the journey to achieve American civil<br />

rights. In the following decade there was<br />

King's letter from Birmingham Jail ('there<br />

comes a time when the cup of endurance<br />

runs over'), his 'I have a dream' speech ('In<br />

spite of the difficulties and frustrations of<br />

the moment, I still have a dream'), and the<br />

250,000 people who gathered at the Lincoln<br />

Memorial to hear him that clay in August<br />

1963. There was the 'bloody Sunday' demonstration<br />

in Selma, Alabama, in March<br />

1965, the hundreds of school children<br />

and teachers who protested and who were<br />

arrested that same year. There were the<br />

many young university students who<br />

were spat upon, abused and assaulted as<br />

they protested non-violently against racial<br />

inequality and injustice.<br />

Three of those students were Michael<br />

Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James<br />

Chaney. They were only in their early<br />

twenties when they entered Mississippi in<br />

January 1964 to support the right of people<br />

there to register to vote. 'Nowhere in<br />

the world is the idea of white supremacy<br />

m ore firmly entrenched, or more cancerous,<br />

than in Mississippi,' Schwerner said.<br />

22 EUREKA STREET NOVEMBER- DECEMBER 2005