lightfair international - Illuminating Engineering Society

lightfair international - Illuminating Engineering Society

lightfair international - Illuminating Engineering Society

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

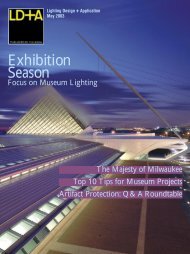

museums of past eras.<br />

The spatial organization of the 300,000 ft 2 structure is<br />

composed of groups of distinctly shaped galleries that Gehry<br />

swirled around a central atrium and froze before colliding<br />

with one another. The catalytic space is the 50 m high atrium—a<br />

kindred gesture to the Guggenheim’s now symbolic<br />

rotunda in New York.<br />

The galleries range in size and shapes, from rectilinear conventional<br />

forms to curvilinear walls. At other times they seem<br />

like spaces within spaces, sometimes separated by partial height<br />

walls that act like visual funnels. Ceiling heights range from 4.5<br />

to 20 m, arranged in flat, sloped, or curving planes, at times<br />

interrupted by rectilinear skylights with organic shaped wells or<br />

structural beams. Each space has its own unique spatial quality<br />

and character, so much so that the gallery designers nicknamed<br />

them “Nemo,” “Zorro,” “the Boot,” “the Boat,” and so on.<br />

Outsiders on the Inside<br />

“As an outsider it was intriguing to observe the Bilbao studio<br />

designers prepare for a design review,” Enrique Rojas said of his<br />

experience working with Gehry’s studio. “They scurried<br />

around to pull together the assortment of large scale models to<br />

an assemblage approximately 6 x 12 ft in size. Crude as the<br />

forms seemed, they fit beautifully. Minutes before the design<br />

session, the team gathered in almost orchestra form and waited<br />

for the conductor to descend from the upper floor.<br />

“Gehry moved pieces here and there, studied the shapes and<br />

one got the distinct sense that he used every square inch of that<br />

building to express his ideas. Everyone listened with absolute<br />

silence and attention.”<br />

Without the use of the large scale “work models” of the<br />

gallery spaces, it would have been almost impossible to imagine<br />

the geometry and luminous qualities of each gallery. The<br />

designers explored numerous ideas for providing indirect and<br />

object lighting placement—from movable light-columns to<br />

Gehry loves sunlight but precious artwork<br />

doesn’t. To minimize light damage to certain<br />

types of artwork, the museum established<br />

a maximum combined illumination level<br />

of 20 fc incident on the art surface.<br />

pendant horizontal ladders and to<br />

“pick-up sticks” suspended from<br />

concealed motorized lowering<br />

devices and catwalks.<br />

To study the placement of object<br />

(i.e., art) lighting, the designers used a<br />

series of vertical cross section diagrams<br />

to help establish strategic fixture<br />

locations (set at the intersection<br />

between 30 degrees from nadir and<br />

1.57 m above floor level) to light the<br />

art walls and possible sculpture or<br />

temporary wall-mounted exhibits. To<br />

keep their sense of scale in these large<br />

and colossal spaces, which were<br />

drawn in metric scale, Zaferiou and<br />

Rojas often sketched in people and<br />

possible sculptural art pieces. During one of his visits in Bilbao,<br />

Zaferiou was shocked to see Claes Oldenburg’s Swiss Knife<br />

exhibited in the Boat Gallery, “just as we had amusingly shown<br />

it in our lighting study sketches three years before the opening.”<br />

Let the Sun Shine In!<br />

Frank Gehry loves sunlight and the Guggenheim’s conservation<br />

staff fears it, and with good cause. To minimize ultraviolet<br />

and infrared radiation damage to certain types of sensitive artwork,<br />

the museum established a maximum combined illumination<br />

level of 20 fc (215 lx) incident on the art surface, with a<br />

2:1 uniformity ratio on the display walls.<br />

Lam Partners Inc.’s capability in understanding and predicting<br />

daylight illumination levels and direct sunlight path travel<br />

in the exhibition spaces was an important part of the lighting<br />

analysis process. Given the large-scale gallery study models<br />

produced by Gehry’s office, physical model testing was the best<br />

way to study and measure the amount and effects of daylight<br />

and sun path entering the art display areas.<br />

The designers were thankful for Gehry’s models, since there<br />

is no substitute method available for observing daylighting<br />

design in a building, especially in structures of the museum’s<br />

complexity. A case in point was the visual information that the<br />

models relayed to the designers. During daylight testing they<br />

noticed that in the large high spaces with skylights, the ceiling<br />

went dark during strong daylight conditions. Working with<br />

accurate physical models, Zaferiou and Rojas detected the need<br />

to add indirect ambient light to balance the brightness ratios<br />

between the skylight wells and adjacent ceiling planes.<br />

To help quantify and measure the natural lighting, the<br />

designers used the firm’s proprietary software program called<br />

SunScan (developed by Robert Osten, Principal) to test the<br />

architect’s study models. The program reads information<br />

measured through light sensors that are placed in the models<br />

and normalizes the data for the latitude in Bilbao, Spain (or<br />

anywhere on the globe).<br />

To record the sunlight paths, a special rotating table was<br />

designed that calibrates the sun’s geometry between the test site<br />

and the project site. A miniature video camera was installed in<br />

the models to record the daily sun path in each gallery for different<br />

times of the year at typical Summer, Winter, and<br />

Equinox daylight conditions. The invaluable information<br />

recorded in the videos was enhanced with dubbed in music<br />

and visual graphics to label hours of the day and seasonal conditions<br />

at a local television studio and then presented to the<br />

museum’s staff for evaluation.<br />

This Guggenheim Museum has more daylight fenestration<br />

than most museums, but through the use of carefully selected<br />

glazing materials (made up high daylight-low UV-transmission<br />

glass, frit glass sandwiched with UV absorbing interlayer) and<br />

motorized shades the light levels are maintained according to<br />

the museum’s criteria.<br />

Lighting a Modern Masterpiece<br />

The lighting design for this uniquely modern building is<br />

responsive to the complex nature and power of the major volumes<br />

and interstitial crevices, which seem to multiply at every<br />

turn and junction. “Without our constant coordination with<br />

the design team and review of the work models it would have<br />

been impossible to layout our design in two-dimensional format,”<br />

explains Rojas. The design team’s intent was to create<br />

spaces which evoked the “artist-in-residence” idea, and the<br />

lighting design would contribute to this goal.<br />

Unlike American lighting designers, Europeans seem to<br />

design with higher levels of glare tolerance and use fluorescent<br />

and metal halide sources in addition to incandescent sources.<br />

Given the high ceilings in the museum, the selection of<br />

European lamps was limiting. After researching light sources<br />

and fixture manufacturers in the European market, and considering<br />

special 220 V electrical power characteristics in Spain,<br />

it became clear that the fixtures for the<br />

galleries would be custom designed.<br />

“The building design presented<br />

physical and conceptual lighting challenges,”<br />

says Zaferiou. The physical<br />

challenges had to deal with complex<br />

geometry of unusually tall ceilings<br />

and curving walls. The conceptual<br />

challenge was driven by Gehry’s goal<br />

to create a flexible lighting system that<br />

did not “scar” the ceiling with permanent<br />

lines of recessed track lighting<br />

and that would be relatively easy to<br />

maintain. Gehry instructed the lighting<br />

designers to “create a bag of lighting<br />

tricks,” and informed them that<br />

he “would not be opposed to using a<br />

In the galleries, a family of lamps was<br />

needed that had a range of wattages<br />

and beamspreads to properly illuminate<br />

the artwork in these diverse spaces.<br />

non-traditional system of lighting, as long as it was not too visible<br />

and not an aesthetic imposition in the building.”<br />

The designers worked with the architect’s highly creative<br />

staff to further develop a unique power-point and power-bar<br />

system that Gehry first conceived for the Weisman Museum in<br />

Minneapolis, MN. Special recessed, structural outlet boxes<br />

with split-wired receptacles occur in a regular 2 m 2 pattern on<br />

all the gallery ceilings, and are regarded as power-points. An<br />

individual object light fixture can be directly attached to these<br />

points on special clamping bars (power-bars) with built-in<br />

receptacles, which can be secured to hold between two and six<br />

fixtures, depending on the length of the power-bar. The bars<br />

can rotate 360 degrees on the power-points, which then offers<br />

more mounting position flexibility than a conventional track<br />

system. A fixture can be located almost anywhere on a gallery<br />

ceiling. In some of the taller galleries, power-points are also<br />

installed on the upper wall surfaces and in light wells for additional<br />

aiming flexibility.<br />

The special power-bar clamping system proved to be a cost<br />

effective alternative to custom curved track, and it is not limited<br />

to any fixture manufacturer. Retractable magnetic covers<br />

painted to match the ceiling conceal the power-points that are<br />

not in use and therefore minimize visual clutter and the scarring<br />

of the ceiling plane.<br />

The Details<br />

In the galleries which have ceiling heights beyond reach by<br />

motorized lifts, it was ultimately decided to provide 11 m high<br />

catwalks in order to suspend the object lights, ambient wall<br />

washers and uplights, and the work lights, and to facilitate<br />

maintenance access without disturbing the art.<br />

Since dimming for light reduction is not desirable in museum<br />

lighting due to color temperature shift, a family of lamps<br />

with a range of wattages and beamspreads was necessary to<br />

illuminate artwork in these diverse spaces. The generous range<br />

42 LD+A/April 1999<br />

LD+A/April 1999 43