Art Un ticle I.1 ited Sta In the ates News - Woodring College of ...

Art Un ticle I.1 ited Sta In the ates News - Woodring College of ...

Art Un ticle I.1 ited Sta In the ates News - Woodring College of ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

"Those who arrive by age 12 or 13 make a quick transition to English—that's <strong>the</strong> dividingline," says Rumbaut, who has studied language assimilation in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Un</strong><strong>ited</strong> <strong>Sta</strong>tes for threedecades. "It's a piece <strong>of</strong> cake for those who arrive much earlier on, because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dominance<strong>of</strong> English in every medium in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Un</strong><strong>ited</strong> <strong>Sta</strong>tes, from video to <strong>the</strong> <strong>In</strong>ternet. English wins."<strong>In</strong> addition, Spanish isn't <strong>the</strong> only fast-growing language in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Un</strong><strong>ited</strong> <strong>Sta</strong>tes: Chinese,Tagalog, Vietnamese, and Arabic have also seen impressive gains since 1990, whileEuropean languages that were once common in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Un</strong><strong>ited</strong> <strong>Sta</strong>tes (such as French, German,and Polish) are becoming less prevalent. But Rumbaut says that <strong>the</strong> children <strong>of</strong> newimmigrants speaking o<strong>the</strong>r languages will almost invariably turn to English as <strong>the</strong>ir primarytongue."The fate <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong>se languages is to succumb to rapid assimilation," says Rumbaut. "Theidea that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Un</strong><strong>ited</strong> <strong>Sta</strong>tes will devolve into riots and become Quebec unless everybodyspeaks English and English only, is absolutely not true. Demography will take care <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>problem itself—it is not really a policy issue."More Than One-Half <strong>of</strong> All Immigrants 'Very Pr<strong>of</strong>icient' in EnglishThe number <strong>of</strong> Americans speaking a language at home o<strong>the</strong>r than English has more thandoubled since 1980, reflecting <strong>the</strong> influx <strong>of</strong> millions <strong>of</strong> immigrants to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Un</strong><strong>ited</strong> <strong>Sta</strong>tes inrecent decades, particularly Spanish-speaking immigrants from Latin America. About 31million U.S. residents speak Spanish at home—easily making it <strong>the</strong> second-most spokenlanguage in <strong>the</strong> country.The idea that speaking languages o<strong>the</strong>r than English hinders full participation <strong>of</strong> U.S.citizenship has substantial public support. For example, in a Los Angeles Times poll <strong>of</strong>California voters after <strong>the</strong>ir 1998 vote to end bilingual education in that state, three out <strong>of</strong>every four agreed with <strong>the</strong> statement: "If you live in America, you need to speak English." 4 Amajority <strong>of</strong> Hispanics share this attitude, according to a new Pew Hispanic Center survey: 57percent <strong>of</strong> Hispanics say that "immigrants have to speak English to say that <strong>the</strong>y are part <strong>of</strong>American society." 5But a majority <strong>of</strong> those who speak languages o<strong>the</strong>r than English at home report <strong>the</strong>mselvesalready very pr<strong>of</strong>icient in English, according to 2004 data from <strong>the</strong> American CommunitySurvey (see Table 1). Fewer than 50 percent <strong>of</strong> people who use Spanish or ano<strong>the</strong>r non-English language at home speak English less than "very well"—including 48 percent <strong>of</strong> thosewho speak Spanish. Almost 70 percent <strong>of</strong> U.S. adults ages 18 to 64 who spoke Spanish in <strong>the</strong>home said <strong>the</strong>y also spoke English ei<strong>the</strong>r "well" or "very well." 6Table 1Language Spoken at Home by U.S. Residents Ages 5 and Older, 2004Primary language© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights ReservedEstimate(millions)Speaks English lessthan "very well"<strong>In</strong> millionsPercentageLanguage o<strong>the</strong>r than English 49.63 22.31 44.94%Spanish 30.52 14.64 47.96%O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>In</strong>do-European language 9.63 3.32 34.42%2

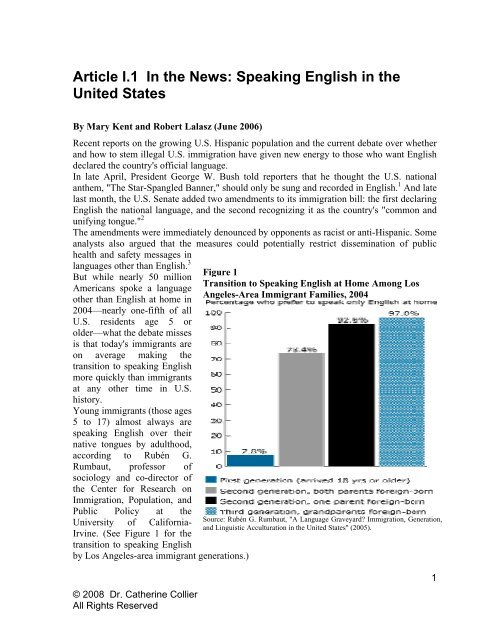

Asian/Pacific-Islander language 7.61 3.10 49.50%O<strong>the</strong>r languages 1.86 0.54 29.25%Source: U.S. Census Bureau, <strong>Un</strong><strong>ited</strong> <strong>Sta</strong>tes: Selected Social Characteristics: 2004 (2004)."The last people you have to tell that English is important are immigrants," says Rumbaut."English is already <strong>the</strong> de facto language <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country and <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world."The Transition to English Acceler<strong>ates</strong>U.S. immigrants are making <strong>the</strong> transition to speaking English much more quickly than didpast immigrants. Historically, this transition took three generations, with adult immigrantswho <strong>of</strong>ten did not learn English, children who were bilingual in English and <strong>the</strong>ir parents'language, and a third generation that spoke English almost exclusively.Today, however, more first- and second-generation Americans are becoming fluent inEnglish. <strong>In</strong> a study that followed more than 5,200 second-generation immigrant children in<strong>the</strong> Miami and San Diego school systems, Rumbaut and Princeton <strong>Un</strong>iversity pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong>sociology Alejandro Portes found that 99 percent spoke fluent English and less than one-thirdmaintained fluency in <strong>the</strong>ir parents' tongues by age 17. 7<strong>In</strong>deed, Census Bureau data for 2000 show that more than 67 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 6.5 million U.S.children ages 5 to 17 who spoke Spanish in <strong>the</strong>ir homes also spoke English "very well,"while 86 percent spoke English ei<strong>the</strong>r "very well" or "well" (see Table 2).Table 2Ability to Speak English for U.S. Residents Ages 5-17, 2000Primary language© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights ReservedEstimate(millions)English speaking levelVery well(millions)%Well(millions)Spanish 6.53 4.40 67.34 1.24 32.66O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>In</strong>do-European language 1.54 1.19 77.67 0.23 22.33Asian/Pacific-Islander language 1.15 0.80 69.56 0.24 30.44O<strong>the</strong>r languages 0.31 0.25 80.60 0.42 19.40Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2000 Supplementary Survey Summary Tables, table P035 (2006).Similar percentages <strong>of</strong> children who spoke a language o<strong>the</strong>r than English or Spanish at homealso spoke English "well" or "very well." The Census data also show that <strong>the</strong>se children arelearning English at higher r<strong>ates</strong> than ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>ir parents or grandparents.Ano<strong>the</strong>r study conducted by Rumbaut shows that more than 73 percent <strong>of</strong> second-generationimmigrants in Sou<strong>the</strong>rn California who have two foreign-born parents prefer to speakEnglish at home instead <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir native tongue (see Figure 1). 8 By <strong>the</strong> third generation, morethan 97 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se immigrants—Mexican, Salvadoran, Guatemalan, Filipino, Chinese,Korean, and Vietnamese—prefer to speak only English at home."The single most important indicator <strong>of</strong> how readily any speaker will switch to English andbecome fluent is <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> arrival, followed by level <strong>of</strong> education and length <strong>of</strong> stay," says%3

<strong>Art</strong>icle I.2 Are Signed Languages "Real"Languages?By Dr. Laura Ann PetittoEvidence from American Sign Language and Langue des SignesQuébécoiseReprinted from Reprinted from: Signpost (<strong>In</strong>ternationalQuarterly <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sign Linguistics Association), vol. 7, No. 3.1-10. French and Spanish translations available on request.<strong>In</strong> <strong>the</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> 1993, a Mr. Gilles Read sent me a letter. Mr.Read is <strong>the</strong> General Manager <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Montreal MetropolitanDeaf Community Center. He wrote to me seeking adocument that addressed <strong>the</strong> question <strong>of</strong> whe<strong>the</strong>r signedlanguages were "real" languages. At <strong>the</strong> time, I was surprisedto discover that <strong>the</strong>re did not exist a document that simply and directly asked and answeredhis question, especially in one single source. Therefore, I wrote Mr. Read a letter, <strong>of</strong> whichan expanded version appears below. To be sure, I could not possibly have summarized forMr. Read all studies <strong>of</strong> signed languages to date, as fortunately thousands now exist. Nor wasit possible to summarize <strong>the</strong> many important studies <strong>of</strong> signed languages that have beenundertaken outside <strong>of</strong> North America. <strong>In</strong>deed, Mr. Read was preparing to attend meetings in<strong>the</strong> Provincial government <strong>of</strong> Québec and he needed a document that specifically addressed<strong>the</strong> linguistic status <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two main signed languages used in <strong>the</strong>se regions, in particularAmerican Sign Language (ASL) and Langue des Signes Québécoise (LSQ). Thus, my goalwas to draw toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> disparate studies on signed languages that have been conducted in avery clear way, and to show how <strong>the</strong>y bear on <strong>the</strong> critical question, "are signed languages'real' languages?" Although <strong>the</strong> examples are drawn from studies <strong>of</strong> ASL and LSQ, <strong>the</strong>general structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> arguments presented here are applicable to arguments for <strong>the</strong> "reallanguage" status <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r natural signed languages around <strong>the</strong> world.<strong>In</strong>troductionThis paper summarizes over thirty years <strong>of</strong> scientific research, which, in one form or ano<strong>the</strong>r,addresses <strong>the</strong> following question: Are <strong>the</strong> natural signed languages that are used by manydeaf persons throughout <strong>the</strong> world "real" languages? Below I demonstrate that signedlanguages are indeed "real" languages. I do so by drawing evidence from three categories <strong>of</strong>scientific research, including (i) Linguistic analyses <strong>of</strong> natural signed languages, (ii)Sociolinguistic analyses <strong>of</strong> natural signed languages, and, crucially, (iii) Biological analyses<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> status <strong>of</strong> natural signed languages in <strong>the</strong> human brain.© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved5

identical linguistic properties found in both ASL and in spoken language. For example,studies <strong>of</strong> Langue des Signes Québécoise (LSQ), <strong>the</strong> signed language used in Québec andelsewhere in Canada by culturally French Deaf persons, have revealed that it is a fullyautonomous natural language with a unique etymology (history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> derivation <strong>of</strong> its signs):It is a grammatically distinct language from ASL and it is a grammatically distinct languagefrom <strong>the</strong> signed language used in France. <strong>In</strong>deed, LSQ is a complete and richly complexlanguage. It has "phonological," morphological, syntactic, discourse, pragmatic, and semanticstructures that are entirely equal in complexity and richness to that which is found in anyspoken (or signed) language (e.g., Petitto, 1987b&c; Petitto & Charron, 1988; Petitto,Charron, & Briére, 1990; see also Brentari, 1991; Lacerte, 1991; Miller, 1991). Takentoge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> scientific study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> linguistic status <strong>of</strong> signed languages has demonstratedthat complete human languages are not restricted to <strong>the</strong> speech channel. Signed languagespossess all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> linguistic features that have been identified as being <strong>the</strong> essential, universalfeatures <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world's spoken languages.Sociolinguistic studies have been conducted that examine <strong>the</strong> social and cultural conditionsunder which natural signed languages are used. These studies have revealed that signedlanguages exhibit <strong>the</strong> identical sociolinguistic patterns observed in spoken languages. Likespoken languages, signed languages undergo change over time, and <strong>the</strong>y demonstrate <strong>the</strong>same types <strong>of</strong> historical change that are seen in spoken languages. For example, signedlanguages exhibit <strong>the</strong> same processes <strong>of</strong> expanding <strong>the</strong>ir lexicons (<strong>the</strong> set <strong>of</strong> words or signs ina language) through sign borrowings, loan signs, and compounding (e.g., see Battison, 1978;Klima & Bellugi, 1979; Woodward, 1976; Woodward & Erting, 1975). As is commonamong users <strong>of</strong> a particular spoken language (e.g., English, French), signed language userswithin distinct signed language communities (e.g., ASL or LSQ communities) demonstrateregional accents in <strong>the</strong>ir signing, lexical (=sign) variation depending on socio-economicstatus, and lexical variation depending on <strong>the</strong> language user's age, sex, and educationalbackground (e.g., Battison, 1978). Fur<strong>the</strong>r, users <strong>of</strong> distinct signed languages abide bylanguage-specific (tacit) rules <strong>of</strong> politeness, turn-taking, and o<strong>the</strong>r discourse (conversational)patterns found in spoken languages (e.g., Hall, 1983; Wilbur & Petitto, 1981, 1983). As canbe seen with users <strong>of</strong> particular spoken languages, users <strong>of</strong> particular signed languages <strong>of</strong>tenshare beliefs, attitudes, and customs with o<strong>the</strong>rs who use <strong>the</strong> same language, binding <strong>the</strong>minto a distinct cultural group--one that is not simply <strong>the</strong> signed version (or Deaf translation)<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> majority spoken culture within which <strong>the</strong>y reside (e.g., Hall, 1989; Lane, 1989; Padden& Humphries, 1988; Ru<strong>the</strong>rford, 1988). <strong>In</strong> Canada, for example, <strong>the</strong> ASL and <strong>the</strong> LSQsigned language communities, respectively, are bound by a distinct collection <strong>of</strong> beliefs andattitudes that are expressed in a variety <strong>of</strong> ways. These include, for example, (a) <strong>the</strong> existence<strong>of</strong> poetry in ASL or in LSQ, (b) humor and jokes in ASL or in LSQ, (c) indigenous artisticexpression through <strong>the</strong>atre and dance in ASL or in LSQ, (d) indigenous meeting customs andtraditions (e.g., witness <strong>the</strong> many Deaf social clubs in <strong>the</strong> ASL or <strong>the</strong> LSQ community, aswell as in <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r signed language communities throughout <strong>the</strong> world), (e) Deaf religiousorganizations in ASL or in LSQ, (f) Deaf sports events in ASL or in LSQ, (g) Deafnewspapers and o<strong>the</strong>r publications for <strong>the</strong> ASL or <strong>the</strong> LSQ communities, and so forth. <strong>In</strong>summary, sociolinguistic studies <strong>of</strong> natural signed languages have determined that <strong>the</strong>ydemonstrate strikingly similar patterns <strong>of</strong> change, variation, and social and cultural use thatare common to <strong>the</strong> world's spoken languages.7© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved

Biological analyses <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> status <strong>of</strong> natural signed languages in <strong>the</strong> humanbrainThough <strong>the</strong>re is now wider acceptance that signed languages are "real" languages based onlinguistic and socio-cultural grounds, a persistent and powerful misconception remains. Themisconception can be summarized as follows: "Spoken language is fundamentally better thansigned language; sign is 'inferior' ('secondary') to speech. The notion that signed languagesare real languages, but somehow "inferior" or lower than <strong>the</strong> higher status spoken languages,is reminiscent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> late 19th century division <strong>of</strong> spoken languages into "high" and "low"languages. (Here, languages deemed "high" were those used in Western Europe, and "low or"primitive" languages were those used elsewhere by aboriginal peoples.) Though subsequentscientific studies have shown that <strong>the</strong> high-low classification <strong>of</strong> spoken languages is whollyfallacious, similar attitudes regarding spoken versus signed languages have not been subjectto <strong>the</strong> same sorts <strong>of</strong> scientific scrutiny. The above view about signed languages runsespecially deep because it invokes biology. At <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> misconception is <strong>the</strong> notionthat signed languages are biologically inferior to spoken languages. Why is this so? Theanswer involves a three-tiered set <strong>of</strong> related assumptions: First, a common quip is "mostpeople speak, so speaking must be better." I call this <strong>the</strong> "more is better" assumption. Second,drawing from <strong>the</strong> observation that "most people speak," people have fur<strong>the</strong>r assumed that thismust "prove" that speech, alone, has been selected for over <strong>the</strong> development or evolution <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> species (or, in "phylogeny"). Third, <strong>the</strong> assumption that speech has been selected for overhuman evolution, has implicitly been used to support <strong>the</strong> core, critical assumption about <strong>the</strong>biological foundations <strong>of</strong> human language: <strong>the</strong> brain must be neurologically set for speechearly in <strong>the</strong> developmental history <strong>of</strong> individual human organisms (or, in "ontogeny"). Thisthird assumption has generally been regarded as being true because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> remarkableregularities observed in very early spoken language acquisition. Noting such universalregularities in, for example, <strong>the</strong> timing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> onset <strong>of</strong> speaking children's early vocalbabbling and first words, researchers have concluded that <strong>the</strong> brain and its' maturation mustbe attuned to perceiving and producing spoken language input (per se) in early life. To besure, a typical answer to <strong>the</strong> question "how does early human language acquisition begin?" isthat it is <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong>, and wholly determined by, <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> anatomy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>vocal tract and <strong>the</strong> neuroanatomical and neurophysiological mechanisms involved in <strong>the</strong>motor control <strong>of</strong> speech production (e.g., Locke, 1983; MacNeilage & Davis, 1990;MacNeilage, Studdert-Kennedy, & Lindblom, 1985; van der Stelt & Koopmans-van Beinum,1986). An implicit assumption that underlies such views is that spoken languages are bettersu<strong>ited</strong> to <strong>the</strong> brain's maturational needs in development. Put ano<strong>the</strong>r way, <strong>the</strong> view <strong>of</strong> humanbiology that underlies <strong>the</strong> prevailing third assumption is that <strong>the</strong> human brain is "hardwired"for speech and that speech is "special" or "privileged." On this view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brain, <strong>the</strong>n, signedlanguages can only be regarded as being "biologically" inferior to (or "lower" than) spokenlanguages. By extension, many educators and researchers, alike, have assumed that speech isbetter in order to achieve "normal" language acquisition.© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved8

Is <strong>the</strong>re any evidence in support <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> alleged "inferior" biological status<strong>of</strong> signed languages?Surprisingly, with <strong>the</strong> exception <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> studies reported below, <strong>the</strong> critical studies required toevaluate <strong>the</strong> above assumptions have not been conducted. As noted above, most allcontemporary answers to questions about <strong>the</strong> biological foundation <strong>of</strong> language have beenbased on <strong>the</strong> core assumption that very early language acquisition is tied to speech. There is,however, a fatal flaw with this assumption: Given that only languages utilizing <strong>the</strong> speechmodality are studied, it is in principle, a priori, impossible to find data that would doanything but support this hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. Only when a modality o<strong>the</strong>r than speech is analyzedcan any generalization about <strong>the</strong> brain's predisposition for speech be evaluated, and,<strong>the</strong>refore, whe<strong>the</strong>r signed languages have <strong>the</strong> same or different status in <strong>the</strong> human brain.The critical ontogenetic evidence regarding <strong>the</strong> biological status <strong>of</strong> naturalsigned languageOver <strong>the</strong> past 12 years, research in my own laboratory has been directed at understanding <strong>the</strong>biological foundations <strong>of</strong> human language. My central aim has been to discover <strong>the</strong> specificbiological and environmental factors that toge<strong>the</strong>r permit early language acquisition to beginin our species. Studies <strong>of</strong> very early signed language acquisition <strong>of</strong>fer an especially clearwindow into <strong>the</strong> biological foundations <strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> human language (be it spoken or signed), aswell as its biological status in <strong>the</strong> brain. Spoken and signed languages utilize differentperceptual modalities (sound versus sight), and <strong>the</strong> motor control <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tongue and hands aresubserved by different neural substr<strong>ates</strong> in <strong>the</strong> brain. Comparative analyses <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>selanguages, <strong>the</strong>n, provide key insights into <strong>the</strong> specific neural architecture that determinesearly human language acquisition in our species. If, as has been argued, very early humanlanguage acquisition is under <strong>the</strong> exclusive control <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> maturation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mechanisms forspeech production and/or speech perception, <strong>the</strong>n spoken and signed languages should beacquired in radically different ways. At <strong>the</strong> very least, fundamental differences in <strong>the</strong> timecourse and nature <strong>of</strong> spoken versus signed language acquisition would suggest that each maybe processed and represented in different ways, presumably due to <strong>the</strong>ir differing biologicalstatus in <strong>the</strong> human brain. To investigate <strong>the</strong>se issues, I have conducted numerouscomparative studies <strong>of</strong> children acquiring spoken languages (English or French) and childrenacquiring signed languages (American Sign Language or Langue des Signes Québécoise),ages birth through 36 months.The empirical findings from my cross-linguistic and cross-modal studiesare clear(i) Deaf children who are exposed to signed languages from birth, acquire <strong>the</strong>se languages onan identical maturational time course as hearing children acquire spoken languages. Deafchildren acquiring signed languages from birth do so without any modification, loss, or delayto <strong>the</strong> timing, content, and maturational course associated with reaching all linguisticmilestones observed in spoken language. Beginning at birth, and continuing through age 3© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved9

and beyond, speaking and signing children exhibit <strong>the</strong> identical stages <strong>of</strong> languageacquisition. These include <strong>the</strong> (a) "syllabic babbling stage" (7-10 months, approx.) as well aso<strong>the</strong>r developments in babbling (e.g., "variegated babbling," ages 10-12 months, and "jargonbabbling," ages 12 months and beyond; Petitto, 1984, 1987a&b; Petitto & Marentette,1991a), (b) "first word stage" (11-14 months, approx.; e.g., Petitto, 1985, 1986, 1988, 1992,1993b; Petitto & Marentette, 1991b; Petitto, Costopoulos, & Stevens, in preparation), and(c)"first two-word stage" (16-22 months, approx.; Petitto, 1987a; Petitto & Marentette,1991b). Though some researchers have claimed that "first signs" are acquired earlier than"first words," subsequent analyses have revealed that <strong>the</strong> claim is wholly unfounded1.Surprising similarities are also observed in deaf and hearing children's timing onset and use<strong>of</strong> gestures. Signing and speaking children produce strikingly similar pre-linguistic (9-12months) and post-linguistic communicative gestures (12-48 months; e.g., Petitto, 1984,1987a, 1992). They do not produce more (or more elaborate) gestures, even though linguistic"signs" (identical to <strong>the</strong> "word") and communicative gestures reside in <strong>the</strong> same modality,and even though some signs and gestures are formationally and referentially similar. <strong>In</strong>stead,deaf children consistently differentiate linguistic signs from communicative gesturesthroughout development, acquiring and using each in <strong>the</strong> same ways observed in hearingchildren (see Petitto, 1992). Signing children exhibit highly similar patterns <strong>of</strong> latergrammatical development as well (ages 22-36 months, approx., and beyond), includingsystematic morphological and syntactic developments (e.g., "over-regularizations," negation,question formation, and so forth; e.g., Petitto, 1984, 1987a; see also Newport & Meier,1985). Throughout development, signing and speaking children exhibit remarkably similarcomplexity in <strong>the</strong>ir utterances. For example, analyses <strong>of</strong> young ASL and LSQ children'ssocial and conversational patterns <strong>of</strong> language use over time, as well as <strong>the</strong> types <strong>of</strong> thingsthat <strong>the</strong>y "talk" about over time (its' semantic and conceptual content, categories, andreferential scope), have demonstrated unequivocally that <strong>the</strong>ir language acquisition follows<strong>the</strong> identical path as is observed in age-matched hearing children acquiring spoken language(Charron & Petitto, 1991; Petitto, 1992; Petitto & Charron, 1988). (ii) Hearing childrenexposed to both signed and spoken languages from birth (e.g., one parent signs and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rparent speaks) demonstrate no preference for speech whatsoever, even though <strong>the</strong>y can hear.<strong>In</strong>stead, <strong>the</strong>y acquire both <strong>the</strong> signed and <strong>the</strong> spoken language to which <strong>the</strong>y are beingexposed on an identical maturational timetable (<strong>the</strong> timing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> onset <strong>of</strong> all linguisticmilestones occurs at <strong>the</strong> same time in both <strong>the</strong> signed and spoken modalities). <strong>In</strong> addition,such children acquire <strong>the</strong> signed and spoken languages to which <strong>the</strong>y are being exposed (e.g.,ASL and English, or, LSQ and French) in <strong>the</strong> same manner that o<strong>the</strong>r children acquire twodifferent spoken languages from birth in a "bilingual" home, for example, one with spokenFrench and spoken English (Petitto, 1985, 1986, 1993b; see especially, Petitto, 1993a, andPetitto, Costopoulos, & Stevens, in preparation). (iii) Hearing children who are exposedexclusively to signed languages from birth through early childhood (i.e., <strong>the</strong>y receive little orno systematic spoken language input whatsoever), achieve each and every linguisticmilestone (manual babbling, "first signs," "first two-signs," and so forth) in signed languageon <strong>the</strong> identical time course as has been observed for hearing children acquiring spokenlanguage and deaf children acquiring signed language. Thus, entirely normal languageacquisition occurred in <strong>the</strong>se hearing children (a) without <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> auditory and speechperception mechanisms, and (b) without <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> motoric mechanisms for <strong>the</strong>production <strong>of</strong> speech (Petitto, a & b; Petitto, Costopoulos, & Stevens, in preparation).10© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved

Significance <strong>of</strong> biological studies <strong>of</strong> early signed and spoken languageacquisitionDespite <strong>the</strong> modality differences, signed and spoken languages are acquired in virtuallyidentical ways. The differences that were observed between children acquiring a signedlanguage versus children acquiring a spoken language were no greater than <strong>the</strong> differencesobserved between hearing children learning one spoken language, say, French, versusano<strong>the</strong>r, say, Finnish. Such findings cast serious doubt on <strong>the</strong> core hypo<strong>the</strong>sis in very earlyspoken language acquisition: that <strong>the</strong> maturation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mechanisms for <strong>the</strong> production and/orperception <strong>of</strong> speech, exclusively determines <strong>the</strong> time course and content <strong>of</strong> early humanlanguage acquisition. These findings fur<strong>the</strong>r challenge <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis that speech (and sound)is critical to normal language acquisition, and <strong>the</strong>y challenge <strong>the</strong> related hypo<strong>the</strong>sis thatspeech is uniquely su<strong>ited</strong> to <strong>the</strong> brain's maturational needs in language ontogeny. If speech,alone, were neurologically set or "privileged" in early brain development, <strong>the</strong>n, for example,<strong>the</strong> hearing infants exposed to both speech and sign from birth might be expected to attemptto glean every morsel <strong>of</strong> speech that <strong>the</strong>y could get from <strong>the</strong>ir environment. Faced implicitlywith a "choice" between speech and sign, <strong>the</strong> very young hearing infant in this context mightbe expected to turn away from <strong>the</strong> sign input, favoring instead <strong>the</strong> speech input, and <strong>the</strong>rebyacquire signs differently (e.g., later). Similarly, deaf and hearing infants exposed only tosigned languages from birth should have demonstrated grossly abnormal patterns <strong>of</strong> languageacquisition. None <strong>of</strong> this happened. What is most interesting about <strong>the</strong>se research findings isthat <strong>the</strong> modality "switch" can be "thrown" after birth regarding whe<strong>the</strong>r a child acquireslanguage on <strong>the</strong> hands or <strong>the</strong> language on <strong>the</strong> tongue. Such findings have led me to propose anew way to construe human language ontogeny (see especially Petitto, 1993a&b). Speechand sound are not critical to human language acquisition. <strong>In</strong>stead, <strong>the</strong>re appears to be astunning, biologically-based equipotentiality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> modalities (spoken and signed) to receiveand produce natural language in ontogeny (Petitto, 1994). The only way that signed andspoken languages could be acquired with such startling similarity, is if <strong>the</strong> brain's <strong>of</strong> allnewborns possess a mechanism that is sensitive to aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> structural regularities <strong>of</strong>natural language, irrespective <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> input modality. Ra<strong>the</strong>r than being exclusively"hardwired" for speech or sound, our species appears to "hardwired" to detect aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>patterning <strong>of</strong> language (specifically, aspects <strong>of</strong> its structural and prosodic regularities; seePetitto, 1993a&b). If <strong>the</strong> environmental input contains <strong>the</strong> requisite patterns unique to naturallanguage, human infants will attempt to produce and to acquire those patterns, irrespective <strong>of</strong>whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> input is signed or spoken. (For a discussion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> specific neural substr<strong>ates</strong> thatunderlie this capacity in ontogeny, as well as <strong>the</strong>ir possible roots in phylogeny, see especiallyPetitto, 1993a&b.) <strong>In</strong> summary, <strong>the</strong> present findings prove wholly false assumptions about<strong>the</strong> "biological inferiority" <strong>of</strong> signed languages relative to spoken languages. Signed andspoken languages are acquired in <strong>the</strong> same ways, and on <strong>the</strong> same maturational time course.With regard to <strong>the</strong> brain and human biology, this indic<strong>ates</strong> that signed and spoken languagesengage <strong>the</strong> same brain-based mechanisms in very early language acquisition.© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved11

Conclusion: Are Signed Languages Real Languages?Results from studies <strong>of</strong> early language acquisition provide especially strong evidencerelevant to assessing whe<strong>the</strong>r signed languages are real languages. Here we see clearly that<strong>the</strong> prevailing assumption about <strong>the</strong> biological foundations <strong>of</strong> human language--indeed, <strong>the</strong>very assumption upon which notions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> alleged biological superiority <strong>of</strong> speech over signrests--is not supported when <strong>the</strong> relevant studies are conducted. Specifically, no evidence wasfound that <strong>the</strong> newborn brain is neurologically set exclusively for speech in early languageontogeny. No evidence was found that speech is biologically more "special," more"privileged," or "higher" in status than sign in early language ontogeny. <strong>In</strong>stead, <strong>the</strong> key,persistent research finding to emerge is this: The biological mechanisms in <strong>the</strong> brain thatunderlie early human language acquisition do not appear to differentiate between spokenversus signed language input. Both types <strong>of</strong> input appear to be processed equally in <strong>the</strong> brain.This provides powerful evidence that signed and spoken languages occupy identical and,crucially, equal biological status in <strong>the</strong> human brain. <strong>In</strong> summary, I have outlined three lines<strong>of</strong> scientific research on <strong>the</strong> status <strong>of</strong> natural signed languages relative to spoken languages,including Linguistic, Sociolinguistic, and Biological research. All three types <strong>of</strong> researchprovide powerful converging evidence that natural signed languages are "real languages,"demonstrating all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> features characteristic <strong>of</strong> language in our species. Thus, <strong>the</strong>re is noscientific reason to exclude ASL or LSQ, or any o<strong>the</strong>r natural signed language, from <strong>the</strong>family <strong>of</strong> languages used by human beings. That signed languages are real languages cannow be considered to be an unequivocal scientific fact.AcknowledgementsI thank Kevin Dunbar, Jamie MacDougall and <strong>the</strong> researchers (students and staff) whoassisted in <strong>the</strong> studies discussed within, and, crucially, <strong>the</strong> Deaf and hearing families who solovingly gave <strong>the</strong>ir time and support to <strong>the</strong>se studies. I also thank <strong>the</strong> following for fundingthis research: Natural Science and Engineering Council <strong>of</strong> Canada, <strong>the</strong> MacDonnell-PewCentre Grant in Cognitive Neuroscience, and <strong>the</strong> McGill-IBM Cooperative Project.Footnotes1 Most all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> claims regarding <strong>the</strong> earlier onset <strong>of</strong> first signs over first words stem fromone group <strong>of</strong> researchers (e.g., Bonvillian, Orlansky, Novack, & Folven, 1983; Folven &Bonvillian, 1991). Recently, a second group <strong>of</strong> researchers (Meier & Newport, 1991) hasbased <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>the</strong>oretical arguments in support <strong>of</strong> a possible "sign advantage" largely onBonvillian et al's claims. The subjects in Bonvillian et al.'s studies are reported to haveproduced <strong>the</strong>ir "first sign" at a mean age <strong>of</strong> 8.2 months (a date that differs from hearingchildren’s' first words, which occurs at approximately 11 months). However, in <strong>the</strong>ir studies,<strong>the</strong> infants' "first signs" were not required to be used in a meaningful or referential way.<strong>In</strong>stead, infant manual productions containing "recognizable adult phonetic forms" withoutany "referential" content, were attributed "sign" status (=lexical or word status). What <strong>the</strong>ywere actually measuring, however, is clear from <strong>the</strong> spoken language acquisition literatureand from my own work: <strong>In</strong> spoken language, we see that hearing infants around ages 7-10months begin production <strong>of</strong> "syllabic babbling," whereupon <strong>the</strong>y produce vocal productionscontaining recognizable adult phonetic forms without any referential content. Similarly, in© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved12

signed language, we see that sign-exposed infants around ages 7-10 months also beginproduction <strong>of</strong> "syllabic babbling," albeit on <strong>the</strong>ir hands (Petitto & Marentette, 1991a). Thus,it would appear that Bonvillian et al., have mislabeled genuine instances <strong>of</strong> manual babblingin sign-exposed infants as being "first signs." Recall that <strong>the</strong>ir date for <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> first signs is8.2 months--which is smack in <strong>the</strong> middle <strong>of</strong> infants' manual (and/or vocal) babbling stage(see also Petitto, 1988, for a discussion <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r methodological considerations associatedwith this research, including <strong>the</strong> over attribution <strong>of</strong> linguistic sign status to <strong>the</strong>se infants nonlinguisticcommunicative gestures).© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved13

<strong>Art</strong>icle I.3 The <strong>In</strong>terpreter: Has a remote Amazoniantribe upended our understanding <strong>of</strong> Language?By John ColapintoOne morning last July, in <strong>the</strong> rain forest <strong>of</strong> northwestern Brazil, Dan Everett, an Americanlinguistics pr<strong>of</strong>essor, and I stepped from <strong>the</strong> pontoon <strong>of</strong> a Cessna floatplane onto <strong>the</strong> beachbordering <strong>the</strong> Maici River, a narrow, sharply meandering tributary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Amazon. On <strong>the</strong> bankabove us were some thirty people--short, dark skinned men, women, and children--someclutching bows and arrows, o<strong>the</strong>rs with infants on <strong>the</strong>ir hips. The people, members <strong>of</strong> a hunterga<strong>the</strong>rertribe called <strong>the</strong> Pirahã, responded to <strong>the</strong> sight <strong>of</strong> Everett--a solidly built man <strong>of</strong> fifty-fivewith a red beard and <strong>the</strong> booming voice <strong>of</strong> a former evangelical minister--with a greeting thatsounded like a pr<strong>of</strong>usion exotic songbirds, a melodic chattering scarcely discernible, to <strong>the</strong>uninitiated, human speech. <strong>Un</strong>related to any o<strong>the</strong>r extant tongue, and based on just eightconsonants and three vowels, Pirahã as one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> simplest sound systems known. Yet itpossesses such a complex array <strong>of</strong> tones, stresses, and syllable lengths that its speakers candispense with <strong>the</strong>ir vowels and consonants altoge<strong>the</strong>r and sing, hum, or whistle conversations. Itis a language so confounding to non-natives that until Everett and his wife, Keren, arrived among<strong>the</strong> Pirahã, as Christian missionaries, in <strong>the</strong> nineteen-seventies, no outsider had succeeded inmastering it. Everett eventually abandoned Christianity, but he and Keren have spent <strong>the</strong> pastthirty years, on and <strong>of</strong>f, living with <strong>the</strong> tribe, and in that time <strong>the</strong>y have learned Pirahã as noo<strong>the</strong>r Westerners have.“Xaoi hi gaisai xigiaihiabisaoaxai ti xabiihai hiatiihi xigio hoihi,” Everett said in <strong>the</strong> tongue'schoppy staccato, introducing me as someone who would be "staying for a short time" in <strong>the</strong>village. The men and women answered in an echoing chorus, "Xa6i hi go6 kaisigiaihlxapagaiso."Everett turned to me. "They want to know what you’re called in 'crooked head’.'" "Crookedhead" is <strong>the</strong> tribe's term for any language that is not Pirahã, and it is a clear pejorative. ThePirahã consider all forms <strong>of</strong> human discourse o<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong>ir own to be laughably inferior, and<strong>the</strong>y are unique among Amazonian peoples in remaining monolingual. They playfully tossed myname back and forth among <strong>the</strong>mselves, altering it slightly with each reiteration, until it becamean unrecognizable syllable. They never uttered it again, but instead gave me a little Pirahã name:Kaaxáoi, that <strong>of</strong> a Pirahã man, from a village downriver, whom <strong>the</strong>y thought I resembled. "That'scompletely consistent with my main <strong>the</strong>sis about <strong>the</strong> tribe," Everett told me later. "They rejecteverything from outside <strong>the</strong>ir world. They just don't want it, and it's been that way since <strong>the</strong> day<strong>the</strong> Brazilians first found <strong>the</strong>m in this jungle in <strong>the</strong> seventeen-hundreds."Everett, who this past fall became <strong>the</strong> chairman <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Languages, Literature, andCultures at Illinois <strong>Sta</strong>te <strong>Un</strong>iversity, has been publishing academic books and papers on <strong>the</strong>Pirahã: (pronounced pee-da-HAN) for more than twenty-five years. But his work remainedrelatively obscure until early in 2005, when he posted on his Web site an ar<strong>ticle</strong> titled "CulturalConstraints on Grammar and Cognition in Pirahã," which was published that fall in <strong>the</strong> journalCultural Anthropology. The ar<strong>ticle</strong> described <strong>the</strong> extreme simplicity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tribe's livingconditions and culture. The Pirahã, Everett wrote, have no numbers, no fixed color terms, noperfect tense, no deep memory, no tradition <strong>of</strong> art or drawing, and no words for "all," "each,""every," "most," or "few" --terms <strong>of</strong> quantification believed by some linguists to be among <strong>the</strong>© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved14

common building blocks <strong>of</strong> human cognition. Everett's most explosive claim, however, was thatPirahã displays no evidence <strong>of</strong> recursion, a linguistic operation that consists <strong>of</strong> inserting onephrase inside ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same type, as when a speaker combines discrete thoughts ("<strong>the</strong> manis walking down <strong>the</strong> street," "<strong>the</strong> man is wearing a top hat") into a single sentence ("The manwho is wearing a top hat is walking down <strong>the</strong> street"). Noam Chomsky, <strong>the</strong> influential linguistic<strong>the</strong>orist, has recently revised his <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> universal grammar, arguing that recursion is <strong>the</strong>cornerstone <strong>of</strong> all languages, and is possible because <strong>of</strong> a uniquely human cognitive ability.Steven Pinker, <strong>the</strong> Harvard cognitive scientist, calls Everett's paper "a bomb thrown into <strong>the</strong>party." For months, it was <strong>the</strong> subject <strong>of</strong> passionate debate on social-science blogs and Listservs.Everett, once a devotee <strong>of</strong> Chomskyan linguistics, insists not only that Pirahã is a "severecounterexample" to <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> universal grammar but also that it is not an isolated case. "Ithink one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reasons that we haven't found o<strong>the</strong>r groups like this," Everett said, "is becausewe've been told, basically, that it's not possible." Some scholars were taken aback by Everett'sdepiction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pirahã as a people <strong>of</strong> seemingly unparalleled linguistic and cultural primitivism."I have to wonder whe<strong>the</strong>r he's some Borgesian fantasist, or some Margaret Mead being stitchedup by <strong>the</strong> locals," one reader wrote in an e-mail to <strong>the</strong> editors <strong>of</strong> a popular linguistics blog.I had my own doubts about Everett's portrayal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pirahã shortly after I arrived in <strong>the</strong> village.We were still unpacking when a Pirahã boy, who appeared to be about eleven years old, ran outfrom <strong>the</strong> trees beside <strong>the</strong> river. Grinning, he showed <strong>of</strong>f a surprisingly accurate replica <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>floatplane we had just landed in. Carved from balsa wood, <strong>the</strong> model was four feet long and hada tapering fuselage, wings, and pontoons, as well as propellers, which were affixed with smallpieces <strong>of</strong> wire so that <strong>the</strong> boy could spin <strong>the</strong> blades with his finger. I asked Everett whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>model contradicted his claim that <strong>the</strong> Pirahã do not make art. Everett barely glanced up. "Theymake <strong>the</strong>m every time a plane arrives," he said. "They don't keep <strong>the</strong>m around when <strong>the</strong>re aren'tany planes. It’s a chain reaction, and someone else will do it, but <strong>the</strong>n eventually it will peterout." Sure enough, I later saw <strong>the</strong> model lying broken and dirty in <strong>the</strong> weeds beside <strong>the</strong> river. Noone made ano<strong>the</strong>r one during <strong>the</strong> six days I spent in <strong>the</strong> village.<strong>In</strong> <strong>the</strong> wake <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> controversy that greeted his paper, Everett encouraged scholars to come to <strong>the</strong>Amazon and observe <strong>the</strong> Pirahã for <strong>the</strong>mselves. The first person to take him up on <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>fer wasa forty-three-year-old American evolutionary biologist named Tecurnseh Fitch, who in 2002 coauthoredan important paper with Chomsky and Marc Hauser, an evolutionary psychologist andbiologist at Harvard, on recursion. Fitch and his cousin Bill, a sommelier based in Paris, weredue to arrive by floatplane in <strong>the</strong> Pirahã village a couple <strong>of</strong> hours after Everett and I did. As <strong>the</strong>plane landed on <strong>the</strong> water, <strong>the</strong> Pirahã, who had ga<strong>the</strong>red at <strong>the</strong> river, began to cheer. The twomen stepped from <strong>the</strong> cockpit, Fitch toting a laptop computer into which he had programmed aweek's worth <strong>of</strong> linguistic experiments that he intended to perform on <strong>the</strong> Pirahã. They werequickly surrounded by curious tribe members. The Fitch cousins, having traveled widely toge<strong>the</strong>rto remote parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world, believed that <strong>the</strong>y knew how to establish an instant rapport withindigenous peoples. They brought <strong>the</strong>ir cupped hands to <strong>the</strong>ir mouths and blew loon calls backand forth. The Pirahã looked on stone-faced. Then Bill began to make a loud popping sound bysnapping a finger <strong>of</strong> one hand against <strong>the</strong> opposite palm. The Pirahã remained impassive. Thecousins shrugged sheepishly and abandoned <strong>the</strong>ir efforts."Usually you can hook people really easily by doing <strong>the</strong>se funny little things," Fitch said later."But <strong>the</strong> Pirahã kids weren't buying it, and nei<strong>the</strong>r were <strong>the</strong>ir parents. Everett snorted. "It's notpart <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir nature," he said. "So <strong>the</strong>y're not interested."© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved15

A few weeks earlier, I had called Fitch in Scotland, where he is a pr<strong>of</strong>essor at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Un</strong>iversity <strong>of</strong>St. Andrews. "I'm seeing this as an exploratory fact-finding trip," he told me. “I want to see withmy own eyes how much <strong>of</strong> this stuff that Dan is saying seems to check out."Everett is known among linguistics experts for orneriness and impatience with academicdecorum. He was born into a working-class family in Holtville, a town on <strong>the</strong> California-Mexicoborder, where his hard-drinking fa<strong>the</strong>r, Leonard, worked variously as a bartender, a cowboy, anda mechanic. "I don't think we had a book in <strong>the</strong> house," Everett said. "To my Dad, people whotaught at colleges and people who wore ties were 'sissies'-all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m. I suppose some <strong>of</strong> that isstill in me." Everett’s chief exposure to intellectual life was through his mo<strong>the</strong>r, a waitress, whodied <strong>of</strong> a brain aneurysm when Everett was eleven. She brought home Reader's Digest condensedbooks and a set <strong>of</strong> medical encyclopedias, which Everett attempted to memorize. <strong>In</strong> high school,he saw <strong>the</strong> movie “My Fair Lady” and thought about becoming a linguist, because, he laterwrote, Henry Higgins's work "attracted me intellectually, and because it looked like phoneticianscould get rich."As a teen-ager, Everett played <strong>the</strong> guitar in rock bands (his keyboardist later became an earlymember <strong>of</strong> Iron Butterfly) and smoked pot and dropped acid, until <strong>the</strong> summer <strong>of</strong> 1968, when hemet Keren Graham, ano<strong>the</strong>r student at El Capitan High School, in Lakeside. The daughter <strong>of</strong>Christian missionaries, Keren was brought up among <strong>the</strong> Satere people in nor<strong>the</strong>astern Brazil.She inv<strong>ited</strong> Everett to church and brought him home to meet her family. "They were loving andcaring and had all <strong>the</strong>se groovy experiences in <strong>the</strong> Amazon," Everett said. "They supported meand told me how great I was. This was just not what I was used to." On October 4, 1968, at <strong>the</strong>age <strong>of</strong> seventeen, he became a born-again Christian. "I felt that my life had changed completely,that I had stepped from darkness into light-all <strong>the</strong> expressions you hear." He stopped using drugs,and when he and Keren were eighteen <strong>the</strong>y married. A year later, <strong>the</strong> first <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir three childrenwas born, and <strong>the</strong>y began preparing to become missionaries.<strong>In</strong> 1976, after graduating with a degree in Foreign Missions from <strong>the</strong> Moody Bible <strong>In</strong>stitute <strong>of</strong>Chicago, Everett enrolled with Keren in <strong>the</strong> Summer <strong>In</strong>stitute <strong>of</strong> Linguistics, known as S.I.L., aninternational evangelical organization that seeks to spread God's Word by translating <strong>the</strong> Bibleinto <strong>the</strong> languages <strong>of</strong> pre-literate societies. They were sent to Chiapas, Mexico, where Kerenstayed in a hut in <strong>the</strong> jungle with <strong>the</strong> couple's children-by this time, <strong>the</strong>re were three-- whileEverett underwent grueling field training. He endured fifty-mile hikes and survived for severaldays deep in <strong>the</strong> jungle with only matches, water, a rope, a machete, and a flashlight.The couple was given lessons in translation techniques, for which Everett proved to have a gift.His friend Peter Gordon, a linguist at Columbia <strong>Un</strong>iversity who has published a paper on <strong>the</strong>absence <strong>of</strong> numbers in Pirahã, says that Everett regularly impresses academic audiences with ademonstration in which he picks from among <strong>the</strong> crowd a speaker <strong>of</strong> a language that he hasnever heard. 'Within about twenty minutes, he can tell you <strong>the</strong> basic structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> languageand how its grammar works," Gordon said. "He has incredible breadth <strong>of</strong> knowledge, is really,really smart, knows stuff inside out.” Everett’s talents were obvious to <strong>the</strong> faculty at S.I.L., wh<strong>of</strong>or twenty years had been trying to make progress in Pirahã, with little success. <strong>In</strong> October,1977, at S.I.L.’s invitation, Everett, Keren, and <strong>the</strong>ir three small children moved to Brazil, first toa city called Belem, to learn Portuguese, and <strong>the</strong>n, a year later, to a Pirahã village at <strong>the</strong> mouth <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Maici River. “At that time, we didn’t know that Pirahã was linguistically so hard,” Kerentold me.There are about three hundred and fifty Pirahã spread out in small villages along <strong>the</strong> Maici andMarmelos Rivers. The village that I vis<strong>ited</strong> with Everett was typical: seven huts made by© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved16

propping palm-frond ro<strong>of</strong>s on top <strong>of</strong> four sticks. The huts had dirt floors and no walls orfurniture, except for a raised platform <strong>of</strong> thin branches to sleep on. These fragile dwellings, inwhich a family <strong>of</strong> three or four might live, lined a path that wound through low brush and grassnear <strong>the</strong> riverbank. The people keep few possessions in <strong>the</strong>ir huts – pots and pans, a machete, aknife – and make no tools o<strong>the</strong>r than scraping implements (used for making arrowheads), looselywoven palm-leaf bags, and wood bows and arrows. Their only ornaments are simple necklacesmade from seeds, teeth, fea<strong>the</strong>rs, beds, and soda-can pull-tabs, which <strong>the</strong>y <strong>of</strong>ten get from traderswho barter with <strong>the</strong> Pirahã for Brazil nuts, wood, and sorva (a rubbery sap used to make chewinggum), and which <strong>the</strong> tribe members wear to ward <strong>of</strong>f evil spirits.<strong>Un</strong>like o<strong>the</strong>r hunter-ga<strong>the</strong>rer tribes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Amazon, <strong>the</strong> Pirahã have resisted efforts bymissionaries and government agencies to teach <strong>the</strong>m farming. They maintain tiny, weed-infestedpatches <strong>of</strong> ground a few steps into <strong>the</strong> forest, where <strong>the</strong>y cultivate scraggly manioc plants. “Thestuff that’s growing in this village was ei<strong>the</strong>r planted by somebody else or it’s what grows whenyou spit <strong>the</strong> seed out,” Everett said to me one morning as we walked through <strong>the</strong> village.Subsisting almost entirely on fish and game, which <strong>the</strong>y catch and hunt daily, <strong>the</strong> Pirahã haveignored lessons in preserving meats by salting or smoking, and <strong>the</strong>y produce only enoughmanioc flour to last a few days. (The Kawahiv, ano<strong>the</strong>r Amazonian tribe that Everett hasstudied, make enough to last for months.) One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir few concessions to modernity is <strong>the</strong>irdress: <strong>the</strong> adult men wear T-shirts and shorts that <strong>the</strong>y get from traders; <strong>the</strong> women wear plaincotton dresses that <strong>the</strong>y sew <strong>the</strong>mselves."For <strong>the</strong> first several years I was here, I was disappointed that I hadn't gone to a 'colorful' group<strong>of</strong> people," Everett told me, "I thought <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people in <strong>the</strong> Xingu, who paint <strong>the</strong>mselves and use<strong>the</strong> lip pl<strong>ates</strong> and have <strong>the</strong> festivals. But <strong>the</strong>n I realized that this is <strong>the</strong> most intense culture that Iwould ever have hoped to experience. This a culture that's invisible to <strong>the</strong> naked eye, but that isincredibly powerful, <strong>the</strong> most powerful culture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Amazon, nobody has resisted change likethis in <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Amazon, and maybe <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world."According to <strong>the</strong> best guess <strong>of</strong> archeologists, <strong>the</strong> Pirahã arrived in <strong>the</strong> Amazon between tenthousand and forty thousand years ago, after bands <strong>of</strong> Homosapiens from Eurasia migrated to <strong>the</strong>Americas over <strong>the</strong> Bering Strait. The Pirahã were once part <strong>of</strong> a larger <strong>In</strong>dian group called <strong>the</strong>Mura, but had split from <strong>the</strong> main tribe by <strong>the</strong> time <strong>the</strong> Brazilians first encountered <strong>the</strong> Mura, in1714. The Mura went on to learn Portuguese and to adopt Brazilian ways, and <strong>the</strong>ir language isbelieved to be extinct. The Pirahã, however, retreated deep into <strong>the</strong> jungle.<strong>In</strong> 1921, <strong>the</strong> anthropologist Curt Nimuendajú spent time among <strong>the</strong> Pirahã and noted that <strong>the</strong>yshowed "little interest in <strong>the</strong> advantages <strong>of</strong> civilization" and displayed "almost no signs <strong>of</strong>permanent contact with civilized people."S.I.L. first made contact with <strong>the</strong> Pirahã nearly fifty years ago, when a missionary couple, Arloand Vi Heinrichs, joined a settlement on <strong>the</strong> Marmelos. The Heinrichses stayed for six and a halfyears, struggling to become pr<strong>of</strong>icient in <strong>the</strong> language. The phonemes (<strong>the</strong> sounds from whichwords are constructed) were exceedingly difficult, featuring nasal whines and sharp intakes <strong>of</strong>breath, and sounds made by popping or flapping <strong>the</strong> lips. <strong>In</strong>dividual words were hard to learn,since <strong>the</strong> Pirahã habitually whittle nouns down to single syllables. Also confounding was <strong>the</strong>tonal nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> language: <strong>the</strong> meanings <strong>of</strong> words depend on changes in pitch. (The words for"friend" and "enemy" differ only in <strong>the</strong> pitch <strong>of</strong> a single syllable.) The Heinrichses' task wasfur<strong>the</strong>r complicated because Pirahã, like a few o<strong>the</strong>r Amazonian tongues, has male and femaleversions: <strong>the</strong> women use one fewer consonant than <strong>the</strong> men do.© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved17

“We struggled even getting to <strong>the</strong> place where we felt comfortable with <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> agrammar," Heinrichs told me. It was two years before he attempted to translate a Bible story; hechose <strong>the</strong> Prodigal Son from <strong>the</strong> Book <strong>of</strong> Luke. Heinrichs read his halting translation to a Pirahãmale. "He kind <strong>of</strong> nodded and said, in his way, “That's interesting,” Heinrichs recalled.”But <strong>the</strong>rewas no spiritual understanding-it had no emotional impact. It was just a story." After sufferingrepeated bouts <strong>of</strong> malaria, <strong>the</strong> couple was reassigned by S.I.L. to administrative jobs in <strong>the</strong> city<strong>of</strong> Brasilia, and in 1967 <strong>the</strong>y were replaced with Steve Sheldon and his wife, Linda. Sheldonearned a master's degree in linguistics during <strong>the</strong> time he spent with <strong>the</strong> tribe, and he wasfrustrated that Pirahã refused to conform to expected patterns-as he and his wife complained inworkshops with S.I.L. consultants. “We would say, 'It just doesn't seem that <strong>the</strong>re's any way thatit does X, Y, or Z,' " Sheldon recalled, "And <strong>the</strong> standard answer--since this typically doesn'thappen in languages-was 'Well, it must be <strong>the</strong>re, just look a little harder.'"Sheldon's anxiety over his slow progress was acute. He began many mornings by getting sick tohis stomach. <strong>In</strong> 1977, after spending ten years with <strong>the</strong> Pirahã, he was promoted to director <strong>of</strong>S.I.L. in Brazil and asked <strong>the</strong> Everetts to take his place in <strong>the</strong> jungle. Everett and his wife werewelcomed by <strong>the</strong> villagers, but it was months before <strong>the</strong>y could conduct a simple conversation inPirahã. “There are very few places in <strong>the</strong> world where you have to learn a language with nolanguage in common," Everett told me. "It's called a monolingual field situation." He had beentrained in <strong>the</strong> technique by his teacher at S.I.L., <strong>the</strong> late Kenneth L. Pike, a legendary fieldlinguist and <strong>the</strong> chairman <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> linguistics department at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Un</strong>iversity <strong>of</strong> Michigan. Pike, whocreated a method <strong>of</strong> language analysis called tagmemics, taught Everett to start with commonnouns. "You find out <strong>the</strong> word for stick,'" Everett said. "Then you try to get <strong>the</strong> expression for'two sticks,' and for 'one stick drops to <strong>the</strong> ground,' 'two sticks drop to <strong>the</strong> ground.' You have toact everything out, to get some basic notion <strong>of</strong> how <strong>the</strong> clause structure works-where <strong>the</strong> subject,verb, and object go."The process is difficult, as I learned early in my visit with <strong>the</strong> Pirahã. One morning, whileapplying bug repellent, I was watched by an older Pirahã man, who asked Everett what I wasdoing. Eager to communicate with him in sign language, I pressed toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> thumb and indexfinger <strong>of</strong> my right hand and weaved <strong>the</strong>m though <strong>the</strong> air while making a buzzing sound with mymouth. Then I brought my fingers to my forearm and slapped <strong>the</strong> spot where my fingers hadalighted. The man looked puzzled and said to Everett, "He hit himself." I tried again-this timemaking a more insistent buzzing.The man said to Everett, "A plane land on his arm." WhenEverett explained to him what I was doing, <strong>the</strong> man studied me with a look <strong>of</strong> pitying contempt<strong>the</strong>n turned away. Everett laughed. "You were trying to tell him something about your generalstate--that bugs bo<strong>the</strong>r you," he said. "They never talk that way and <strong>the</strong>y could never understandit. Bugs are a part <strong>of</strong> life.""O.K.," I said. "But I’m surprised he didn't know I was imitating an insect.""Think <strong>of</strong> how cultural that is," Everett said, "The movement <strong>of</strong> your hand. The sound. Even <strong>the</strong>way we represent animals is cultural."Everett had to bridge many such cultural gaps in order to gain more than a superficial grasp <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> language. "I went into <strong>the</strong> jungle, helped <strong>the</strong>m make fields, went fishing with <strong>the</strong>m," he said."You cannot become one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m, but you've got to do as much as you can to feel and absorb <strong>the</strong>language.” The tribe, he maintains, has no collective memory that extends back more than one ortwo generations, and no original creation myths. Marco Antonio Gonçalves, an anthropologist atFederal <strong>Un</strong>iversity <strong>of</strong> Rio de Janeiro, spent eighteen months with <strong>the</strong> Pirahã in <strong>the</strong> nineteeneightiesand wrote a dissertation on <strong>the</strong> tribe's beliefs. Gonçalves, who spoke lim<strong>ited</strong> Pirahã,© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved18

agrees that <strong>the</strong> tribe has no creation myths but argues that few Amazonian tribes do. Whenpressed about what existed before <strong>the</strong> Pirahã and <strong>the</strong> forest, Everett says, <strong>the</strong> tribespeopleinvariably answer, "It has always been this way."Everett also learned that <strong>the</strong> Pirahã have no fixed words for colors, and instead use descriptivephrases that change from one moment to <strong>the</strong> next. "So if you show <strong>the</strong>m red cup, <strong>the</strong>y're likely tosay, 'This looks like blood,'" Everett said. "Or <strong>the</strong>y could say, 'This is like vrvcum' a local berrythat <strong>the</strong>y use to extract a red dye."By <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir first year, Dan Everett had a working knowledge <strong>of</strong> Pirahã. Keren tutoredKaaxáoi and a child with a monkey <strong>the</strong>y have hunted. <strong>Un</strong>like o<strong>the</strong>r Amazon tribes, <strong>the</strong>Pirahã have resisted efforts by missionaries and government agencies to teach <strong>the</strong>mfarming, and subsist almost entirely on fish and game.© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved19

herself by strapping a cassette recorder around her waist and listening to audiotapes while sheperformed domestic tasks. (The Everetts lived in a thatch hut that was slightly larger and moresophisticated than <strong>the</strong> huts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pirahã; it had walls and a storage room that could be locked.)During <strong>the</strong> family’s second year in <strong>the</strong> Amazon, Keren and <strong>the</strong> Everetts' eldest child, Shannon,contracted malaria, and Keren lapsed into a coma. Everett borrowed a boat from river traders andtrekked through <strong>the</strong> jungle for days to get her to a hospital. As soon as she was discharged,Everett returned to <strong>the</strong> village. (Keren recuperated in Belem for several months before joininghim.) "Christians who believe in <strong>the</strong> Bible believe that it is <strong>the</strong>ir job to bring o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>the</strong> joy <strong>of</strong>salvation," Everett said. "Even if <strong>the</strong>y’re murdered, beaten to death, imprisoned-that's what youdo for God.<strong>Un</strong>til Everett arrived in <strong>the</strong> Amazon, his training in linguistics had been lim<strong>ited</strong> to fieldtechniques. "I wanted as little formal linguistic <strong>the</strong>ory as I could get by with," he told me. "Iwanted <strong>the</strong> basic linguistic training to do a translation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> New Testament." This changedwhen S.I.L. lost its contract with <strong>the</strong> Brazilian government to work in <strong>the</strong> Amazon. S.I.L. urged<strong>the</strong> Everetts to enroll as graduate students at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sta</strong>te <strong>Un</strong>iversity <strong>of</strong> Campinas (UNICAMP), in<strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> Sao Paulo, since <strong>the</strong> government would give <strong>the</strong>m permission to continue living ontribal lands only if <strong>the</strong>y could show that <strong>the</strong>y were linguists intent on recording an endangeredlanguage. At UNICAMP, in <strong>the</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> 1978, Everett discovered Chomsky's <strong>the</strong>ories. "For me, itwas ano<strong>the</strong>r conversion experience," he said.<strong>In</strong> <strong>the</strong> late fifties, when Chomsky, <strong>the</strong>n a young pr<strong>of</strong>essor at M.I.T., first began to attract notice,behaviorism dominated <strong>the</strong> social science. According to B. F. Skinner, children learn words andgrammar by being praised for correct usage, much as lab animals learn to push a lever thatsupplies <strong>the</strong>m with food. <strong>In</strong> 1959, in a demolishing review <strong>of</strong> Skinner's book "Verbal Behavior,"Chomsky wrote that <strong>the</strong> ability <strong>of</strong> children to create grammatical sentences that <strong>the</strong>y have neverheard before proves that learning to speak does not depend on imitation, instruction, or rewards.As he put it in his book "Reflections on Language" (1975), "To come to know a human languagewould be an extraordinary intellectual achievement for a creature not specifically designed toaccomplish this task."Chomsky hypo<strong>the</strong>sized that a specific faculty for language is encoded in <strong>the</strong> human brain atbirth. He described it as a language organ, which is equipped with an immutable set <strong>of</strong> rules--auniversal grammar--that is shared by all languages, regardless <strong>of</strong> how different <strong>the</strong>y appear to be.The language organ, Chomsky said, cannot be dissected in <strong>the</strong> way that a liver or a heart can, butit can be described through detailed analyses <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> abstract structures underlying language. "Bystudying <strong>the</strong> properties <strong>of</strong> natural languages, <strong>the</strong>ir structure, organization, and use," Chomskywrote, "we may hope to gain some understanding <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> specific characteristics <strong>of</strong> humanintelligence. We may hope to learn something about human nature."Beginning in <strong>the</strong> nineteen-fifties, Chomskyans at universities around <strong>the</strong> world engaged informal analyses <strong>of</strong> language, breaking sentences down into ever more complex tree diagrams thatshowed branching noun, verb, and prepositional phrases, and also "X-bars," "transformations,""movements," and "deep structures" –Chomsky’s terms for some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> elements that constitute<strong>the</strong> organizing principles <strong>of</strong> all language. ”I’d been doing linguistics at a fairly low level <strong>of</strong>rigor," Everett said. "As soon as you started reading Chomsky’s stuff, and <strong>the</strong> people mostclosely associated with Chomsky, you realized this is a totally different level--this is actuallysomething that looks like science." Everett conceived his Ph.D. dissertation at UNICAMP as astrict Chomskyan analysis <strong>of</strong> Pirahã. Dividing his time between Sao Paulo and <strong>the</strong> Pirahã village,where he collected data, Everett completed his <strong>the</strong>sis in 1983. Written in Portuguese and later© 2008 Dr. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine CollierAll Rights Reserved20