Continental trace fossils and museum exhibits - Geological Curators ...

Continental trace fossils and museum exhibits - Geological Curators ...

Continental trace fossils and museum exhibits - Geological Curators ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

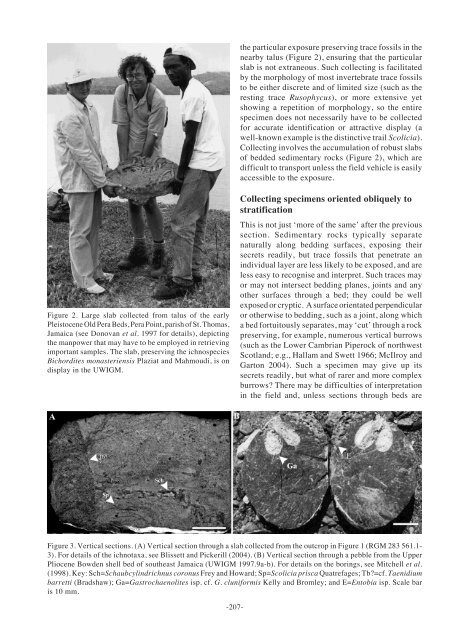

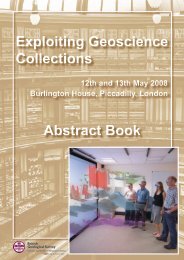

the particular exposure preserving <strong>trace</strong> <strong>fossils</strong> in thenearby talus (Figure 2), ensuring that the particularslab is not extraneous. Such collecting is facilitatedby the morphology of most invertebrate <strong>trace</strong> <strong>fossils</strong>to be either discrete <strong>and</strong> of limited size (such as theresting <strong>trace</strong> Rusophycus), or more extensive yetshowing a repetition of morphology, so the entirespecimen does not necessarily have to be collectedfor accurate identification or attractive display (awell-known example is the distinctive trail Scolicia).Collecting involves the accumulation of robust slabsof bedded sedimentary rocks (Figure 2), which aredifficult to transport unless the field vehicle is easilyaccessible to the exposure.Figure 2. Large slab collected from talus of the earlyPleistocene Old Pera Beds, Pera Point, parish of St. Thomas,Jamaica (see Donovan et al. 1997 for details), depictingthe manpower that may have to be employed in retrievingimportant samples. The slab, preserving the ichnospeciesBichordites monasteriensis Plaziat <strong>and</strong> Mahmoudi, is ondisplay in the UWIGM.Collecting specimens oriented obliquely tostratificationThis is not just ‘more of the same’ after the previoussection. Sedimentary rocks typically separatenaturally along bedding surfaces, exposing theirsecrets readily, but <strong>trace</strong> <strong>fossils</strong> that penetrate anindividual layer are less likely to be exposed, <strong>and</strong> areless easy to recognise <strong>and</strong> interpret. Such <strong>trace</strong>s mayor may not intersect bedding planes, joints <strong>and</strong> anyother surfaces through a bed; they could be wellexposed or cryptic. A surface orientated perpendicularor otherwise to bedding, such as a joint, along whicha bed fortuitously separates, may ‘cut’ through a rockpreserving, for example, numerous vertical burrows(such as the Lower Cambrian Piperock of northwestScotl<strong>and</strong>; e.g., Hallam <strong>and</strong> Swett 1966; McIlroy <strong>and</strong>Garton 2004). Such a specimen may give up itssecrets readily, but what of rarer <strong>and</strong> more complexburrows? There may be difficulties of interpretationin the field <strong>and</strong>, unless sections through beds areFigure 3. Vertical sections. (A) Vertical section through a slab collected from the outcrop in Figure 1 (RGM 283 561.1-3). For details of the ichnotaxa, see Blissett <strong>and</strong> Pickerill (2004). (B) Vertical section through a pebble from the UpperPliocene Bowden shell bed of southeast Jamaica (UWIGM 1997.9a-b). For details on the borings, see Mitchell et al.(1998). Key: Sch=Schaubcylindrichnus coronus Frey <strong>and</strong> Howard; Sp=Scolicia prisca Quatrefages; Tb?=cf. Taenidiumbarretti (Bradshaw); Ga=Gastrochaenolites isp. cf. G. cluniformis Kelly <strong>and</strong> Bromley; <strong>and</strong> E=Entobia isp. Scale baris 10 mm.-207-