SEVEN PAPERS ON EXISTENTIAL ANALYSIS ... - Wagner College

SEVEN PAPERS ON EXISTENTIAL ANALYSIS ... - Wagner College

SEVEN PAPERS ON EXISTENTIAL ANALYSIS ... - Wagner College

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

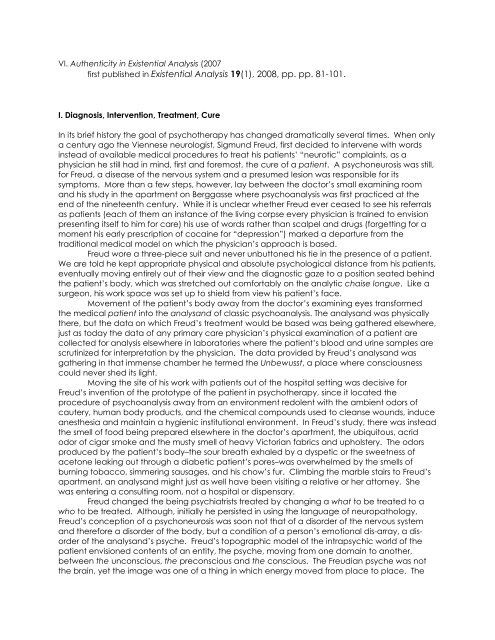

VI. Authenticity in Existential Analysis (2007<br />

first published in Existential Analysis 19(1), 2008, pp. pp. 81-101.<br />

I. Diagnosis, Intervention, Treatment, Cure<br />

In its brief history the goal of psychotherapy has changed dramatically several times. When only<br />

a century ago the Viennese neurologist, Sigmund Freud, first decided to intervene with words<br />

instead of available medical procedures to treat his patients’ “neurotic” complaints, as a<br />

physician he still had in mind, first and foremost, the cure of a patient. A psychoneurosis was still,<br />

for Freud, a disease of the nervous system and a presumed lesion was responsible for its<br />

symptoms. More than a few steps, however, lay between the doctor’s small examining room<br />

and his study in the apartment on Berggasse where psychoanalysis was first practiced at the<br />

end of the nineteenth century. While it is unclear whether Freud ever ceased to see his referrals<br />

as patients (each of them an instance of the living corpse every physician is trained to envision<br />

presenting itself to him for care) his use of words rather than scalpel and drugs (forgetting for a<br />

moment his early prescription of cocaine for “depression”) marked a departure from the<br />

traditional medical model on which the physician’s approach is based.<br />

Freud wore a three-piece suit and never unbuttoned his tie in the presence of a patient.<br />

We are told he kept appropriate physical and absolute psychological distance from his patients,<br />

eventually moving entirely out of their view and the diagnostic gaze to a position seated behind<br />

the patient’s body, which was stretched out comfortably on the analytic chaise longue. Like a<br />

surgeon, his work space was set up to shield from view his patient’s face.<br />

Movement of the patient’s body away from the doctor’s examining eyes transformed<br />

the medical patient into the analysand of classic psychoanalysis. The analysand was physically<br />

there, but the data on which Freud’s treatment would be based was being gathered elsewhere,<br />

just as today the data of any primary care physician’s physical examination of a patient are<br />

collected for analysis elsewhere in laboratories where the patient’s blood and urine samples are<br />

scrutinized for interpretation by the physician. The data provided by Freud’s analysand was<br />

gathering in that immense chamber he termed the Unbewusst, a place where consciousness<br />

could never shed its light.<br />

Moving the site of his work with patients out of the hospital setting was decisive for<br />

Freud’s invention of the prototype of the patient in psychotherapy, since it located the<br />

procedure of psychoanalysis away from an environment redolent with the ambient odors of<br />

cautery, human body products, and the chemical compounds used to cleanse wounds, induce<br />

anesthesia and maintain a hygienic institutional environment. In Freud’s study, there was instead<br />

the smell of food being prepared elsewhere in the doctor’s apartment, the ubiquitous, acrid<br />

odor of cigar smoke and the musty smell of heavy Victorian fabrics and upholstery. The odors<br />

produced by the patient’s body–the sour breath exhaled by a dyspetic or the sweetness of<br />

acetone leaking out through a diabetic patient’s pores–was overwhelmed by the smells of<br />

burning tobacco, simmering sausages, and his chow’s fur. Climbing the marble stairs to Freud’s<br />

apartment, an analysand might just as well have been visiting a relative or her attorney. She<br />

was entering a consulting room, not a hospital or dispensary.<br />

Freud changed the being psychiatrists treated by changing a what to be treated to a<br />

who to be treated. Although, initially he persisted in using the language of neuropathology,<br />

Freud’s conception of a psychoneurosis was soon not that of a disorder of the nervous system<br />

and therefore a disorder of the body, but a condition of a person’s emotional dis-array, a disorder<br />

of the analysand’s psyche. Freud’s topographic model of the intrapsychic world of the<br />

patient envisioned contents of an entity, the psyche, moving from one domain to another,<br />

between the unconscious, the preconscious and the conscious. The Freudian psyche was not<br />

the brain, yet the image was one of a thing in which energy moved from place to place. The