jiafm, 2010-32(2) april-june. - forensic medicine

jiafm, 2010-32(2) april-june. - forensic medicine

jiafm, 2010-32(2) april-june. - forensic medicine

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

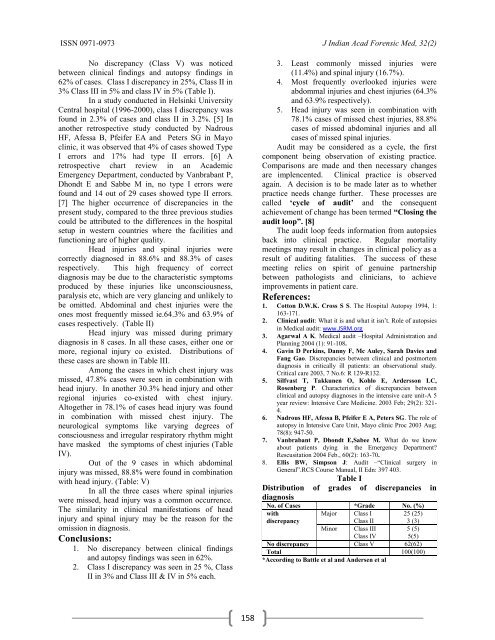

ISSN 0971-0973 J Indian Acad Forensic Med, <strong>32</strong>(2)No discrepancy (Class V) was noticedbetween clinical findings and autopsy findings in62% of cases. Class I discrepancy in 25%, Class II in3% Class III in 5% and class IV in 5% (Table I).In a study conducted in Helsinki UniversityCentral hospital (1996-2000), class I discrepancy wasfound in 2.3% of cases and class II in 3.2%. [5] Inanother retrospective study conducted by NadrousHF, Afessa B, Pfeifer EA and Peters SG in Mayoclinic, it was observed that 4% of cases showed TypeI errors and 17% had type II errors. [6] Aretrospective chart review in an AcademicEmergency Department, conducted by Vanbrabant P,Dhondt E and Sabbe M in, no type I errors werefound and 14 out of 29 cases showed type II errors.[7] The higher occurrence of discrepancies in thepresent study, compared to the three previous studiescould be attributed to the differences in the hospitalsetup in western countries where the facilities andfunctioning are of higher quality.Head injuries and spinal injuries werecorrectly diagnosed in 88.6% and 88.3% of casesrespectively. This high frequency of correctdiagnosis may be due to the characteristic symptomsproduced by these injuries like unconsciousness,paralysis etc, which are very glancing and unlikely tobe omitted. Abdominal and chest injuries were theones most frequently missed ie.64.3% and 63.9% ofcases respectively. (Table II)Head injury was missed during primarydiagnosis in 8 cases. In all these cases, either one ormore, regional injury co existed. Distributions ofthese cases are shown in Table III.Among the cases in which chest injury wasmissed, 47.8% cases were seen in combination withhead injury. In another 30.3% head injury and otherregional injuries co-existed with chest injury.Altogether in 78.1% of cases head injury was foundin combination with missed chest injury. Theneurological symptoms like varying degrees ofconsciousness and irregular respiratory rhythm mighthave masked the symptoms of chest injuries (TableIV).Out of the 9 cases in which abdominalinjury was missed, 88.8% were found in combinationwith head injury. (Table: V)In all the three cases where spinal injurieswere missed, head injury was a common occurrence.The similarity in clinical manifestations of headinjury and spinal injury may be the reason for theomission in diagnosis.Conclusions:1. No discrepancy between clinical findingsand autopsy findings was seen in 62%.2. Class I discrepancy was seen in 25 %, ClassII in 3% and Class III & IV in 5% each.3. Least commonly missed injuries were(11.4%) and spinal injury (16.7%).4. Most frequently overlooked injuries wereabdommal injuries and chest injuries (64.3%and 63.9% respectively).5. Head injury was seen in combination with78.1% cases of missed chest injuries, 88.8%cases of missed abdominal injuries and allcases of missed spinal injuries.Audit may be considered as a cycle, the firstcomponent being observation of existing practice.Comparisons are made and then necessary changesare implencented. Clinical practice is observedagain. A decision is to be made later as to whetherpractice needs change further. These processes arecalled „cycle of audit‟ and the consequentachievement of change has been termed “Closing theaudit loop”. [8]The audit loop feeds information from autopsiesback into clinical practice. Regular mortalitymeetings may result in changes in clinical policy as aresult of auditing fatalities.The success of thesemeeting relies on spirit of genuine partnershipbetween pathologists and clinicians, to achieveimprovements in patient care.References:1. Cotton D.W.K. Cross S S. The Hospital Autopsy 1994, 1:163-171.2. Clinical audit: What it is and what it isn‟t. Role of autopsiesin Medical audit: www.JSRM.org3. Agarwal A K. Medical audit –Hospital Administration andPlanning 2004 (1): 91-108.4. Gavin D Perkins, Danny F, Mc Auley, Sarah Davies andFang Gao. Discrepancies between clinical and postmortemdiagnosis in critically ill patients: an observational study.Critical care 2003, 7 No.6: R 129-R1<strong>32</strong>.5. Silfvast T, Takkunen O, Kohlo E, Ardersson LC,Rosenberg P. Characteristics of discrepancies betweenclinical and autopsy diagnoses in the intensive care unit-A 5year review: Intensive Care Medicine. 2003 Feb; 29(2): <strong>32</strong>1-4.6. Nadrous HF, Afessa B, Pfeifer E A, Peters SG. The role ofautopsy in Intensive Care Unit, Mayo clinic Proc 2003 Aug;78(8): 947-50.7. Vanbrabant P, Dhondt E,Sabee M. What do we knowabout patients dying in the Emergency Department?Rescusitation 2004 Feb., 60(2): 163-70.8. Ellis BW, Simpson J: Audit –“Clinical surgery inGeneral”.RCS Course Manual, II Edn: 397 403.Table IDistribution of grades of discrepancies indiagnosisNo. of Cases *Grade No. (%)withdiscrepancyMajor Class IClass II25 (25)3 (3)Minor Class IIIClass IV5 (5)5(5)No discrepancy Class V 62(62)Total 100(100)*According to Battle et al and Andersen et al158

![syllabus in forensic medicine for m.b.b.s. students in india [pdf]](https://img.yumpu.com/48405011/1/190x245/syllabus-in-forensic-medicine-for-mbbs-students-in-india-pdf.jpg?quality=85)

![SPOTTING IN FORENSIC MEDICINE [pdf]](https://img.yumpu.com/45856557/1/190x245/spotting-in-forensic-medicine-pdf.jpg?quality=85)

![JAFM-33-2, April-June, 2011 [PDF] - forensic medicine](https://img.yumpu.com/43461356/1/190x245/jafm-33-2-april-june-2011-pdf-forensic-medicine.jpg?quality=85)

![JIAFM-33-4, October-December, 2011 [PDF] - forensic medicine](https://img.yumpu.com/31013278/1/190x245/jiafm-33-4-october-december-2011-pdf-forensic-medicine.jpg?quality=85)