Croft (2000: 65) - Noun, verb and adjective are not ... - grandionline.net

Croft (2000: 65) - Noun, verb and adjective are not ... - grandionline.net

Croft (2000: 65) - Noun, verb and adjective are not ... - grandionline.net

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

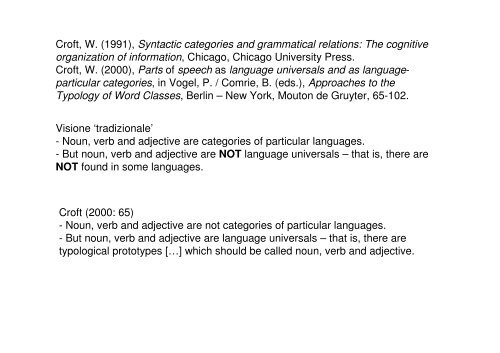

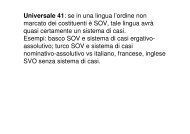

<strong>Croft</strong>, W. (1991), Syntactic categories <strong>and</strong> grammatical relations: The cognitiveorganization of information, Chicago, Chicago University Press.<strong>Croft</strong>, W. (<strong>2000</strong>), Parts of speech as language universals <strong>and</strong> as languageparticularcategories, in Vogel, P. / Comrie, B. (eds.), Approaches to theTypology of Word Classes, Berlin – New York, Mouton de Gruyter, <strong>65</strong>-102.Visione ‘tradizionale’- <strong>Noun</strong>, <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong> <strong>are</strong> categories of particular languages.- But noun, <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong> <strong>are</strong> NOT language universals – that is, there <strong>are</strong>NOT found in some languages.<strong>Croft</strong> (<strong>2000</strong>: <strong>65</strong>)- <strong>Noun</strong>, <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> categories of particular languages.- But noun, <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong> <strong>are</strong> language universals – that is, there <strong>are</strong>typological prototypes […] which should be called noun, <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong>.

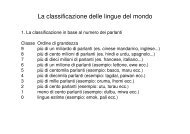

A proper theory of parts of speech that applies to all languages must satisfy thefollowing three conditions in order to be successful.First, there must be a criterion for distinguishing parts of speech from othermorphosyntactically defined subclasses.Second, there must be a cross-linguistically valid <strong>and</strong> uniform set of formalgrammatical criteria for evaluating the universality of the parts-of-speechdistinctions.Third there must be a clear distinction between language universals <strong>and</strong> particularlanguage facts.

“Syntactic categories, including those commonly labelled as parts of speech, <strong>are</strong>derivative from constructions that define them” (<strong>Croft</strong> <strong>2000</strong>: 85)Actual constructions <strong>are</strong> the primitive elementsof syntactic representation <strong>and</strong> categories <strong>are</strong>derived from them: it is a sample of differentconstructions with a common function thatdefines the boundaries of a category or of apart of speech.Typological comparison will sketch a pattern of variation <strong>and</strong> every singlelanguage will fit somewhere in this pattern of variation

<strong>Croft</strong> (1991: 67)ReferenceModificationPredicationObjectsunmarked nounsgenitive,adjectivalisations,PPs on nounspredicate nominals,copulasPropertiesdeadjectival nounsunmarked<strong>adjective</strong>sPredicate <strong>adjective</strong>s,copulasActionsaction nominals,complements,infinitives, gerundsparticiples, relativeclausesunmarked <strong>verb</strong>s

The universal-typological theory of parts of speech embraces constructions with<strong>and</strong> without function-indicating morphosyntax. Function-indicating morphosyntaxovertly encodes the functions of reference, predication <strong>and</strong> modification forvarious classes of lexical items. As such, function-indicating morphosyntax fallsunder the structural coding criterion of the theory of typological markedness. Thetheory of typological markedness […] is a general theory of the relationshipbetween form <strong>and</strong> meaning across languages

The theory defines universal prototypes for the three major parts of speech, butdoes <strong>not</strong> define boundaries for these categories. Boundaries <strong>are</strong> aspects oflanguage-particular grammatical categories, determined by distributionalanalysis”The typological universals do <strong>not</strong> predict the exact behaviour of individuallanguages; rather, they predict that a language will fit somewhere in the pattern ofvariation allowed by typological marking theoryThe behavioural potential criterion specifies that the unmarked memberdisplays at least as wide a range of grammatical behaviour as the markedmember. The behavioural potential criterion is again formulated as animplicational universal. It allows for the possibility of marked members […] tohave the same inflectional possibilities as unmarked members […] in somelanguage. It excludes the possibility of marked members having moreinflectional possibilities than unmarked members.The behavioural potential criterion also allows for the limited or “defective”behaviour of the marked member of a category […] without having to committo the marked member being “in” or “<strong>not</strong> in” the category in a universaltypologicalsense.

Moreover, the terms <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong> do <strong>not</strong> describe language-particulargrammatical categories anyway. They describe cross-linguistic patterns of variation.In particular they describe a prototype. A prototype describes the core of a category;it does <strong>not</strong> say anything about the boundary of a category […]. In fact, the universaltypological theory of parts of speech defines only prototypes for the parts of speech;it does <strong>not</strong> define boundaries. Boundaries <strong>are</strong> features of language-particularcategories.<strong>Noun</strong> > reference to an objectAdjective > modification by a propertyVerb > predication of an action

In such a theoretical framework, we can<strong>not</strong> exclude cases of multiple classmembership <strong>and</strong> of sporadic occurrence of linguistic constructions in atypicalroles.<strong>Croft</strong> (<strong>2000</strong>: 96)“it is quite common cross-linguistically to find a lexical item used in more thanone pragmatic function without overt derivation but with a significant <strong>and</strong> oftensystematic semantic shift […]. The relevant cross-linguistic universal is thatthese shifts <strong>are</strong> always towards the semantic class prototypically associated withthe pragmatic function”

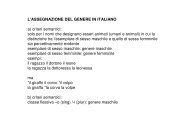

<strong>Noun</strong>GenderLexemeNumberinflected formAdjectiveinflected forminflected form?compound > constructional idiom > suffixcompound > constructional idiom > phrase