- Page 1: HAND OVER FIST PRESS SHEEP IN THE R

- Page 5 and 6: This Volume’s CONTENTS ----------

- Page 7 and 8: ANOTHER OPENING -------------------

- Page 9: HAND OVER FIST PRESS SHEEP IN THE R

- Page 13 and 14: The CONTENTS ----------------------

- Page 15 and 16: OPENING ---------------------------

- Page 18 and 19: 6 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 3

- Page 22 and 23: 10 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 3

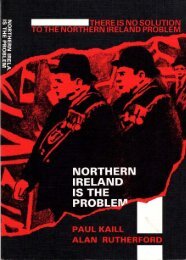

- Page 24 and 25: 12 especially in Northern Ireland w

- Page 26 and 27: 1914-1918 World War One Allied prop

- Page 28 and 29: 16 But this ideological war about t

- Page 31 and 32: Meanwhile, the BBC has confirmed th

- Page 33 and 34: ARMAMENTS MANUFACTURERS MAKE A KILL

- Page 36: a substantially undiscovered part o

- Page 39 and 40: OCTOBER 2015 27

- Page 41 and 42: OPINION ---------------------------

- Page 43: Books are weapons! Hit a tory with

- Page 46: 34 he had been tucked up nicely in

- Page 50 and 51: 38 .3 “Get up”. A foot pushed h

- Page 52 and 53: 40 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 3

- Page 54 and 55: 42 just to save you two dobbers fro

- Page 56: .4 Brad McGlaughlin. And I knew his

- Page 60: So, as social beings inhabiting thi

- Page 63 and 64: OPINION ---------------------------

- Page 65 and 66: Bigger businesses will simply incre

- Page 67: Stars are an important inclusion: t

- Page 70 and 71:

58 sprawling, bike on top of me, un

- Page 72 and 73:

60 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 3

- Page 74 and 75:

62 Ostensibly, Britain went to war

- Page 76 and 77:

64 On the African continent, South

- Page 78 and 79:

men) involved in the South West and

- Page 80 and 81:

68 Nowhere in Smuts’ report to th

- Page 82 and 83:

This wonderful piece of artwork fou

- Page 84 and 85:

72 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 3

- Page 86 and 87:

HAND OVER FIST PRESS 2 0 1 5

- Page 88 and 89:

Alan Rutherford 1984

- Page 90 and 91:

Alan Rutherford

- Page 92 and 93:

4 Alan Rutherford Don’t let this

- Page 94 and 95:

The collective principle asserts th

- Page 96 and 97:

8 services was nowhere near as gene

- Page 98 and 99:

hmm... tony still has those skeleto

- Page 100 and 101:

Alan Rutherford

- Page 102 and 103:

14 What’s going on here? Part of

- Page 104 and 105:

16 a hint at dickensian times to co

- Page 107 and 108:

That’s Why (we don’t comply wit

- Page 110:

22 Among other things they pointed

- Page 114:

26 Even faithful and simple Sancho

- Page 117 and 118:

I WALK THE LINE

- Page 119 and 120:

After your sharp, regular ribs, The

- Page 121 and 122:

Stop putting us in these fucking co

- Page 123 and 124:

Also at: www.disconnectedpress.co.u

- Page 127:

REVIEWED From Another Way of Tellin

- Page 131:

43 • The Portraits Chris Hoare is

- Page 135 and 136:

DECEMBER 2015 47

- Page 137 and 138:

DECEMBER 2015 49

- Page 141:

SERIALSCRIPT ----------------------

- Page 144 and 145:

56 The gunshot was loud against the

- Page 146 and 147:

Something you don’t read everyday

- Page 148 and 149:

The maritime world may be losing it

- Page 151 and 152:

NATURE ----------------------------

- Page 154 and 155:

66 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 4

- Page 156 and 157:

68 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 4

- Page 158 and 159:

70 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 4

- Page 160 and 161:

72 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 4

- Page 162 and 163:

74 Electrif Lycanthrope was the fir

- Page 165 and 166:

Alan Rutherford

- Page 167 and 168:

RANTING ---------------------------

- Page 169 and 170:

WAFFLE ----------------------------

- Page 171 and 172:

SHEEP IN THE ROAD XMAS 2015 5 A POV

- Page 173 and 174:

The CONTENTS ----------------------

- Page 175 and 176:

OPENING ---------------------------

- Page 177 and 178:

MENTION ---------------------------

- Page 179 and 180:

astute neversleeping masters made i

- Page 181:

Ours be the task to enlighten the i

- Page 184:

12 GET ON THE TRAIN From the standp

- Page 187 and 188:

...say what? 15 ‘I said, Assad mu

- Page 189 and 190:

XMAS 2015 17

- Page 191 and 192:

19 ALL TOGETHER NOW! XMAS 2015

- Page 193 and 194:

CAUTIONARY ------------------------

- Page 195 and 196:

From Ben Traven’s The Treasure of

- Page 197 and 198:

BLOODLUST -------------------------

- Page 199 and 200:

27 The unspeakable in pursuit of th

- Page 201 and 202:

dog units and lots of police cars w

- Page 203 and 204:

Once I started to feel better I ask

- Page 205 and 206:

Warwickshire Police were given foot

- Page 207 and 208:

XMAS 2015 35

- Page 209 and 210:

XMAS 2015 37

- Page 211 and 212:

Prejudice and faith have something

- Page 213 and 214:

XMAS 2015 41

- Page 215 and 216:

XMAS 2015 43

- Page 217 and 218:

XMAS 2015 45

- Page 219 and 220:

XMAS 2015 47

- Page 221 and 222:

XMAS 2015 49

- Page 223 and 224:

XMAS 2015 51

- Page 225 and 226:

XMAS 2015 53

- Page 227 and 228:

XMAS 2015 55

- Page 229 and 230:

XMAS 2015 57

- Page 231 and 232:

XMAS 2015 59

- Page 233 and 234:

RUST 61 XMAS 2015

- Page 235 and 236:

63 TOO XMAS 2015

- Page 237 and 238:

WAFFLE ----------------------------

- Page 239 and 240:

SHEEP IN THE ROAD JANUARY 2016 6

- Page 241:

The CONTENTS ----------------------

- Page 245:

MENTION ---------------------------

- Page 248:

and is no longer accessible first h

- Page 251 and 252:

www.caferoyalbooks.com crbnotes.wor

- Page 253 and 254:

HEAVEN HELP THOSE seeking in the AS

- Page 255:

JANUARY 2016 15

- Page 258 and 259:

highlighted in two publications of

- Page 260 and 261:

20 Anti-Capitalist Britain is a col

- Page 263 and 264:

AMBIGRAM --------------------------

- Page 265 and 266:

CONTEMPT --------------------------

- Page 267 and 268:

In the days leading up to the war,

- Page 269 and 270:

Although the Judge found our argume

- Page 271 and 272:

JANUARY 2016 31

- Page 273 and 274:

Ali Ismail Abbas, born 1991, is an

- Page 275 and 276:

JANUARY 2016 35

- Page 277 and 278:

elow: Roy Prockter, left: Birgit V

- Page 279 and 280:

elow: Simon Heywood, left: Sian Cwp

- Page 281 and 282:

JANUARY 2016 41

- Page 283 and 284:

NEWMAN ----------------------------

- Page 285 and 286:

BRIGHT LIGHTS ---------------------

- Page 287 and 288:

Dave was studying the patterns on t

- Page 289 and 290:

‘I never did tell you about Marcu

- Page 292 and 293:

The Branch Secretary 52 Cheltenham

- Page 294 and 295:

BRITISH 54 FOREIGN POLICY SHEEP IN

- Page 297 and 298:

FIBONACCI -------------------------

- Page 299 and 300:

CATASTROPHY -----------------------

- Page 301 and 302:

The fourth bomb’s recovery would

- Page 303:

63 After Palomares the USAF seems t

- Page 306 and 307:

NU R R N 66 U DE G OU D SHEEP IN TH

- Page 308 and 309:

68 REVIEW -------------------------

- Page 310 and 311:

70 The entrance to the exhibition i

- Page 312 and 313:

72 In the ‘Crossings’ section,

- Page 314 and 315:

74 Then we head into the pertinent

- Page 316 and 317:

76 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 6

- Page 318 and 319:

HAND OVER FIST PRESS 2 0 1 6

- Page 320 and 321:

SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 7

- Page 323 and 324:

OPENING ---------------------------

- Page 325 and 326:

They are wrong Lets join together W

- Page 327:

7 Nobody is doing what Joe Sacco is

- Page 330 and 331:

10 Later in life, in my trampship t

- Page 332 and 333:

12 Coke financially supported the N

- Page 334 and 335:

14 In the 1930s, Hugo Boss started

- Page 336 and 337:

16 ‘situation’, they really nee

- Page 340 and 341:

20 EXPLOITED ----------------------

- Page 342 and 343:

Endi Poskovic ... the juxtaposition

- Page 344 and 345:

long-dead stars. where the other bu

- Page 346 and 347:

26 Most of the stars in the sky, in

- Page 348 and 349:

28 stars, there will only be one su

- Page 350 and 351:

30 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 7

- Page 352 and 353:

32 REVIEW -------------------------

- Page 354 and 355:

34 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 7

- Page 356 and 357:

36 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 7

- Page 359 and 360:

SHITARTICLE -----------------------

- Page 361 and 362:

Anarchists suggest that humans are

- Page 363 and 364:

UNDERGROUND 43 FEBRUARY 2016

- Page 365 and 366:

‘Of course, the representation of

- Page 367 and 368:

95 percent of Brit Expats Sent Back

- Page 369 and 370:

FEBRUARY 2016 49

- Page 371 and 372:

JUST ANOTHER SHORT STORY Photograph

- Page 373 and 374:

FEBRUARY 2016 53

- Page 375 and 376:

was quite well paid at the Dunlop f

- Page 377 and 378:

farewells to friends of convenience

- Page 379 and 380:

FEBRUARY 2016 59

- Page 381 and 382:

WAFFLE ----------------------------

- Page 383 and 384:

8 EUROSCEPTICS SHEEP IN THE ROAD EA

- Page 385:

The CONTENTS ----------------------

- Page 388 and 389:

4 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 8

- Page 390 and 391:

It was to that end that we set abou

- Page 392 and 393:

8 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 8

- Page 394 and 395:

of roasting rabbit filled the house

- Page 396 and 397:

12 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 8

- Page 398 and 399:

‘I must stay - to protect you and

- Page 402 and 403:

18 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 8

- Page 404 and 405:

20 When I arrive on the Strand to b

- Page 406 and 407:

22 Britain’s response to what is

- Page 408 and 409:

24 thing” and remains “somethin

- Page 410 and 411:

26 Photograph: Alan Rutherford Chic

- Page 412 and 413:

28 AGE-OLD QUESTION? MARTIN TAYLOR

- Page 414 and 415:

the wasps and flies could get in th

- Page 416 and 417:

32 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 8

- Page 419 and 420:

FOLLY -----------------------------

- Page 421 and 422:

REFERENDUM? DEMOOCRACY? ASK ME SOME

- Page 423 and 424:

They did not want to provoke a resp

- Page 425 and 426:

That is the tragedy of this referen

- Page 427 and 428:

EASTER 2016 43

- Page 429 and 430:

DON’T MARK HIS FACE Hull Prison R

- Page 431 and 432:

EASTER 2016 47

- Page 433 and 434:

and screamed at me to get away from

- Page 435 and 436:

EASTER 2016 51

- Page 437 and 438:

DUBLIN EASTER 1916 Edited from an a

- Page 439 and 440:

British military forces in Ireland,

- Page 441 and 442:

The effect of the book, as each chi

- Page 443 and 444:

EASTER 2016 59

- Page 445 and 446:

61 161 EASTER 2016

- Page 447 and 448:

WAFFLE ----------------------------

- Page 449 and 450:

9 SHEEP IN THE ROAD APRIL 2016 STIL

- Page 451:

The CONTENTS ----------------------

- Page 454 and 455:

... at its core, the cylinder too i

- Page 456 and 457:

Photograph: Alan Rutherford

- Page 458 and 459:

8 In 1649 Gerrard Winstanley and 14

- Page 460 and 461:

Royal is a new imprint within Café

- Page 462:

Nils Burwitz Namibia: Heads or Tail

- Page 466 and 467:

CONSTRUCT-IVISM El Lissitzky was on

- Page 468 and 469:

Artwork: Shepard Fairey

- Page 471 and 472:

UTTER FOLLY -----------------------

- Page 473 and 474:

volatile things, and tampering with

- Page 475 and 476:

In the end, our captivity lasted un

- Page 477 and 478:

a city of iron and fire oozing kero

- Page 479 and 480:

to be targeted, but increasingly de

- Page 481 and 482:

in the pockets of economic deprivat

- Page 483 and 484:

33 by Edmund at nevercomedowncomix.

- Page 485 and 486:

35 APRIL FOOL 2016

- Page 487 and 488:

37 APRIL FOOL 2016

- Page 489 and 490:

39 The images and the comic as a wh

- Page 491 and 492:

INTERVIEW -------------------------

- Page 493:

D. You know, these are great storie

- Page 503:

This building once housed Cheltenha

- Page 512 and 513:

what he really wanted to talk about

- Page 514 and 515:

Photograph: Delia McDevitt

- Page 516 and 517:

and visionaries had been shot in 19

- Page 518 and 519:

68 SHEEP IN THE ROAD : NUMBER 9

- Page 520:

HAND OVER FIST PRESS 2 0 1 6