You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

2019 POLLS: CONTRADICTIONS IN POLITY<br />

I see electoral<br />

corruption amid loud<br />

noise of fight against<br />

corruption<br />

— Nwabueze<br />

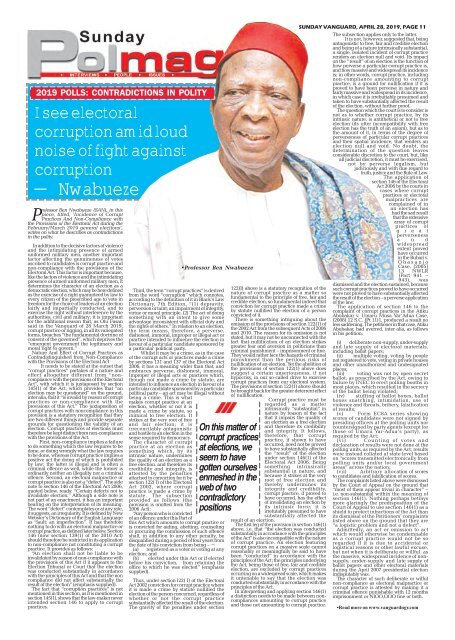

Professor Ben Nwabueze (SAN), in this<br />

piece, titled, ‘Incidence of Corrupt<br />

Practices And <strong>No</strong>n-Compliance with<br />

the Provisions of the Electoral Act during the<br />

February/March 2019 general elections’,<br />

writes on what he describes as contradictions<br />

in the polity.<br />

In addition to the decisive factors of violence<br />

<strong>and</strong> the intimidating presence of armed<br />

uniformed military men, another important<br />

factor affecting the genuineness of votes<br />

ascribed to c<strong>and</strong>idates is corrupt practice <strong>and</strong><br />

non-compliance with the provisions of the<br />

Electoral Act. This factor is important because,<br />

like the factors of violence <strong>and</strong> the intimidating<br />

presence of armed uniformed military men, it<br />

determines the character of an election as a<br />

democratic election, which may be here defined<br />

as the exercise of a right guaranteed by law to<br />

every citizen of the prescribed age to vote in<br />

freedom for the choice of leaders at an election<br />

fairly <strong>and</strong> impartially conducted, <strong>and</strong> to<br />

exercise the right without interference by the<br />

authorities, civil <strong>and</strong> military; it is important<br />

for the additional reason that, as Olu Fasan<br />

said in the Vanguard of 28 March 2019,<br />

corrupt practice or rigging, in all its variegated<br />

forms, breaches “the fundamental doctrine of<br />

consent of the <strong>go</strong>verned”, which deprives the<br />

“emergent <strong>go</strong>vernment the legitimacy <strong>and</strong><br />

moral right to <strong>go</strong>vern.”<br />

Nature And Effect of Corrupt Practices as<br />

Contradistinguished from <strong>No</strong>n-Compliance<br />

with the Provisions of the Electoral Act<br />

It needs to be stated at the outset that<br />

“corrupt practices” partakes of a nature <strong>and</strong><br />

effect altogether different from “noncompliance<br />

with the provisions of the Electoral<br />

Act”, with which it is juxtaposed by section<br />

145(1) of the Act, which provides that “an<br />

election may be questioned” on the ground,<br />

inter alia, that it “is invalid by reason of corrupt<br />

practices or non-compliance with the<br />

provisions of this Act.” The juxtaposition of<br />

corrupt practices with noncompliance in this<br />

provision is a statutory recognition that they<br />

are two different things <strong>and</strong> provide separate<br />

grounds for questioning the validity of an<br />

election. Corrupt practices at elections must<br />

therefore be kept distinct from non-compliance<br />

with the provisions of the Act.<br />

First, non-compliance implies a failure<br />

to do something which the law requires to be<br />

done, or doing wrongly what the law requires<br />

to be done, whereas corrupt practice implies a<br />

positive act the doing of which is prohibited<br />

by law; the latter is illegal <strong>and</strong> is often a<br />

criminal offence as well, while the former is<br />

ordinarily neither an illegality nor a criminal<br />

offence. Second, an electoral malpractice or<br />

corrupt practice is also not a “defect”. The side<br />

note to section 146 of the Electoral Act 2006,<br />

quoted below, reads: “Certain defects not to<br />

invalidate election.” Although a side note is<br />

not part of an enactment, it has an important<br />

bearing on the interpretation of its meaning.<br />

The word “defect” contemplates or at any rate,<br />

it suggests, an irregularity. It is defined by New<br />

Webster’s Dictionary of the English Language<br />

as “fault; an imperfection”. It has therefore<br />

nothing to do with an electoral malpractice or<br />

corrupt practice, as defined later below. Section<br />

146 (now section 139(1) of the 2010 Act)<br />

should therefore be restricted in its application<br />

to non-compliance not constituting a corrupt<br />

practice. It provides as follows:<br />

“An election shall not be liable to be<br />

invalidated by reason of non-compliance with<br />

the provisions of this Act if it appears to the<br />

Election Tribunal or Court that the election<br />

was conducted substantially in accordance<br />

with the principles of this Act <strong>and</strong> that the non<br />

compliance did not affect substantially the<br />

result of the election” (emphasis supplied).<br />

The fact that “corruption practices” is not<br />

mentioned in this section, as it is mentioned in<br />

section 145(1), shows that the law-maker never<br />

intended section 146 to apply to corrupt<br />

practices.<br />

•Professor Ben Nwabueze<br />

Third, the term “corrupt practices” is derived<br />

from the word “corruption” which connotes,<br />

according to the definition of it in Black’s Law<br />

Dictionary, 7th Edition, “(1) depravity,<br />

perversion or taint; an impairment of integrity,<br />

virtue or moral principle. (2) The act of doing<br />

something with an intent to give some<br />

advantage inconsistent with official duty <strong>and</strong><br />

the rights of <strong>others</strong>.” In relation to an election,<br />

the term means, therefore, a perverse,<br />

dishonest, immoral, improper or illegal act or<br />

practice intended to influence the election in<br />

favour of a particular c<strong>and</strong>idate sponsored by<br />

a particular political party.<br />

Whilst it may be a crime, as in the case<br />

of the corrupt acts or practices made a crime<br />

by sections 131 <strong>and</strong> 137 of the Electoral Act<br />

2006, it has a meaning wider than that, <strong>and</strong><br />

embraces perverse, dishonest, immoral,<br />

Improper or illegal acts or practices which,<br />

though not made a crime by statute, are<br />

intended to influence an election in favour of a<br />

particular c<strong>and</strong>idate sponsored by a particular<br />

political party – an act may be illegal without<br />

being a crime. This is what<br />

makes corrupt practice at an<br />

election, whether or not it is<br />

made a crime by statute, so<br />

inimical to free election. It<br />

strikes at the very root of free<br />

<strong>and</strong> fair election; it is<br />

irreconcilably anta<strong>go</strong>nistic<br />

<strong>and</strong> hostile to an election in the<br />

sense required by democracy.<br />

The character of corrupt<br />

practice at an election as<br />

something which, by its<br />

intrinsic nature, undermines<br />

the quality of an election as a<br />

free election. <strong>and</strong> therefore its<br />

credibility <strong>and</strong> integrity, is<br />

attested by the penalties<br />

attached to conviction for it by<br />

section 122( I) of the Electoral<br />

Act 2002, where corrupt<br />

practice is made a crime by<br />

statute. The subsection<br />

provided as follows (the<br />

provision is omitted from the<br />

2006 Act):<br />

“Any person who is convicted<br />

of an offence under this Part of<br />

this Act which amounts to corrupt practice or<br />

is convicted for aiding, abetting, counseling<br />

or procuring the commission of such offence<br />

shall, in addition to any other penalty, be<br />

disqualified during a period of four years from<br />

the date of his conviction from being – ¬<br />

(a) registered as a voter or voting at any<br />

election; <strong>and</strong><br />

(b) elected under this Act or if elected<br />

before his conviction, from retaining the<br />

office to which he was elected” (emphasis<br />

supplied).<br />

Thus, under section l22( I) of the Electoral<br />

Act 2002 conviction for corrupt practice where<br />

it is made a crime by statute nullified the<br />

election of the person concerned, regardless of<br />

whether or not the corrupt practice<br />

substantially affected the result of the election.<br />

The gravity of the penalties under section<br />

On this matter of<br />

corrupt practices<br />

at elections, we<br />

seem to have<br />

<strong>go</strong>tten ourselves<br />

enmeshed in the<br />

web of two<br />

contradictory<br />

positions<br />

122(I) above is a statutory recognition of the<br />

nature of corrupt practice as a matter so<br />

fundamental to the principle of free, fair <strong>and</strong><br />

credible election, so fundamental indeed that<br />

conviction for corrupt practice made a crime<br />

by statute nullified the election of a person<br />

convicted of it.<br />

There is something intriguing about the<br />

omission of the provisions of section 122(1) of<br />

the 2002 Act from the subsequent Acts of 2006<br />

<strong>and</strong> 2010. The reason for its omission is not<br />

stated, but it may not be unconnected with the<br />

fact that nullification of an election strikes<br />

greater fear <strong>and</strong> aversion in politicians than<br />

criminal punishment – imprisonment or fine.<br />

They would rather face the hazards of criminal<br />

punishment than the perilous risks of<br />

nullification of an election. Yet the abolition of<br />

the provisions of section 122(1) above does<br />

suggest a certain unseriousness, if not<br />

hypocrisy, in our so-called drive to exorcise<br />

corrupt practices from our electoral system.<br />

The provisions of section 122(1) above should<br />

be brought back for the greater deterrent effect<br />

of nullification.<br />

Corrupt practice must be<br />

regarded as a matter<br />

intrinsically “substantial” in<br />

nature by reason of the fact<br />

that it impairs the quality of<br />

an election as a free election<br />

<strong>and</strong> therefore its credibility<br />

<strong>and</strong> integrity. It follows,<br />

therefore, that corrupt<br />

practice, if shown to have<br />

occurred, need not be proved<br />

to have substantially affected<br />

the “result” of the election<br />

under section 146(1) of the<br />

Electoral Act 2006. Being<br />

something intrinsically<br />

substantial in nature, <strong>and</strong><br />

because it strikes at the very<br />

root of free election <strong>and</strong><br />

thereby undermines its<br />

integrity <strong>and</strong> credibility,<br />

corrupt practice, if proved to<br />

have occurred, has the effect<br />

of invalidating an election by<br />

its intrinsic force; it is<br />

irrefutably presumed to have<br />

substantially affected the<br />

result of an election.<br />

The first leg of the provision in section 146(1)<br />

above, i.e. that “the election was conducted<br />

substantially in accordance with the principles<br />

of the Act” is also incompatible with the nature<br />

of corrupt practice. An election featuring<br />

corrupt practices on a massive scale cannot<br />

reasonably or meaningfully be said to have<br />

been “conducted” in accordance with the<br />

principles of the Act; the principles underlying<br />

the Act, being those of free, fair <strong>and</strong> credible<br />

election, are excluded by corrupt practices<br />

occurring on a widespread scale, which makes<br />

it untenable to say that the election was<br />

conducted substantially in accordance with the<br />

principles of the Act.<br />

In interpreting <strong>and</strong> applying section 146(1)<br />

a distinction needs to be made between noncompliances<br />

amounting to corrupt practice<br />

<strong>and</strong> those not amounting to corrupt practice.<br />

SUNDAY VANGUARD, APRIL 28, 2019, PAGE 11<br />

The subsection applies only to the latter.<br />

It is not, however, suggested that, being<br />

anta<strong>go</strong>nistic to free, fair <strong>and</strong> credible election<br />

<strong>and</strong> being of a nature intrinsically substantial,<br />

a single, isolated incident of corrupt practice<br />

renders an election null <strong>and</strong> void. Its impact<br />

on the “result” of an election is the function of<br />

how perverse a particular corrupt practice is,<br />

<strong>and</strong> how massive <strong>and</strong> widespread its incidence<br />

is; in other words, corrupt practice, including<br />

non-compliance amounting to corrupt<br />

practice, is a ground for nullification if it is<br />

proved to have been perverse in nature <strong>and</strong><br />

fairly massive <strong>and</strong> widespread in its incidence,<br />

in which case it is irrebuttably presumed <strong>and</strong><br />

taken to have substantially affected the result<br />

of the election, without further proof.<br />

The question which the court is to consider is<br />

not as to whether corrupt practice, by its<br />

intrinsic nature, is antithetical or not to free<br />

election (its utter incompatibility with free<br />

election has the truth of an axiom), but as to<br />

the amount of it, in terms of the degree of<br />

perverseness of particular corrupt practices<br />

<strong>and</strong> their spatial incidence, that renders an<br />

election null <strong>and</strong> void. <strong>No</strong> doubt, the<br />

determination of the question leaves<br />

considerable discretion to the court, but, like<br />

all judicial discretion, it must be exercised,<br />

not by perverse legalism, but<br />

judiciously <strong>and</strong> with due regard to<br />

truth, justice <strong>and</strong> the Rule of Law.<br />

The application of<br />

section 146 of the Electoral<br />

Act 2006 by the courts in<br />

cases where corrupt<br />

practices or electoral<br />

malpractices are<br />

complained of in<br />

an election has<br />

had the sad result<br />

that the extensive<br />

array of corrupt<br />

practices of<br />

g r e a t<br />

perverseness<br />

a n d<br />

widespread<br />

extent proved<br />

t o<br />

have occurred<br />

in the Buhari v.<br />

Obasanjo<br />

Case, [2005]<br />

13 NWLR<br />

(Part 941 –<br />

943), was<br />

dismissed <strong>and</strong> the election sustained, because<br />

such corrupt practices proved to have occurred<br />

were not proved to have substantially affected<br />

the result of the election – a perverse application<br />

of the law.<br />

The application of section 146 to the<br />

complaint of corrupt practices in the Atiku<br />

Abubakar v. Umaru Musa Yar’Adua Case,<br />

(2008) 12 S.C. (Pt 11)1, produced a result no<br />

less saddening. The petitioner in that case, Atiku<br />

Abubakar, had averred, inter alia, as follows<br />

in his petition:<br />

(i) deliberate non-supply, under-supply<br />

<strong>and</strong> late supply of electoral materials,<br />

including ballot papers;<br />

(ii) multiple voting, voting by people<br />

not registered to vote, voting in private houses<br />

<strong>and</strong> other unauthorized <strong>and</strong> undesignated<br />

places;<br />

(iii) voting was not by open secret<br />

ballot, as prescribed by the Act, owing to<br />

failure by INEC to erect polling booths in<br />

most places, which resulted in the secrecy<br />

of the ballot being violated;<br />

(iv) stuffing of ballot boxes, ballot<br />

boxes snatching, intimidation, use of<br />

violence <strong>and</strong> threats, bribery, falsification<br />

of results;<br />

(v) Form EC8A series showing<br />

scores of c<strong>and</strong>idates were not signed by<br />

presiding officers at the polling units nor<br />

countersigned by party agents (except for<br />

those of Umaru Yar-Adua’s party), as<br />

required by the Act;<br />

(vi) Counting of votes <strong>and</strong><br />

declaration of results were not done at the<br />

polling units, as required by the Act; results<br />

were instead collated at state level based<br />

on “scores transmitted electronically from<br />

polling units <strong>and</strong>/or local <strong>go</strong>vernment<br />

areas” across the nation;<br />

(vii) Arbitrary allocation of scores<br />

to c<strong>and</strong>idates <strong>and</strong> falsification of scores.<br />

The complaints listed above were dismissed<br />

by the Court of Appeal on the ground that<br />

“most of them appear trivial in character” –<br />

i.e. non-substantial within the meaning of<br />

section 146(1). <strong>No</strong>thing perhaps betrays<br />

more glaringly the predisposition of the<br />

Court of Appeal to use section 146(1) as a<br />

shield to protect infractions of the Act than<br />

its dismissal of the Petitioners’ complaints<br />

listed above on the ground that they are<br />

“a logistic problem <strong>and</strong> not a defect”.<br />

Admittedly, an act or omission to act<br />

which would otherwise be condemnable<br />

as a corrupt practice would not be so<br />

regarded if it is due to accidental or<br />

logistical reasons or other lawful excuse,<br />

but not when it is deliberate or willful. as<br />

the massive, widespread incidence of nonsupply,<br />

under-supply <strong>and</strong> late supply of<br />

ballot papers <strong>and</strong> other electoral materials<br />

during the April 2007 presidential election<br />

indisputably was.<br />

The character of such deliberate or wilful<br />

non-compliance as electoral malpractice or<br />

corrupt practice is attested by making it a<br />

criminal offence punishable with 12 months<br />

imprisonment or NlOO,OOO fine or both.<br />

•Read more on www.vanguardngr.com