NCC Magazine: Fall 2019

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

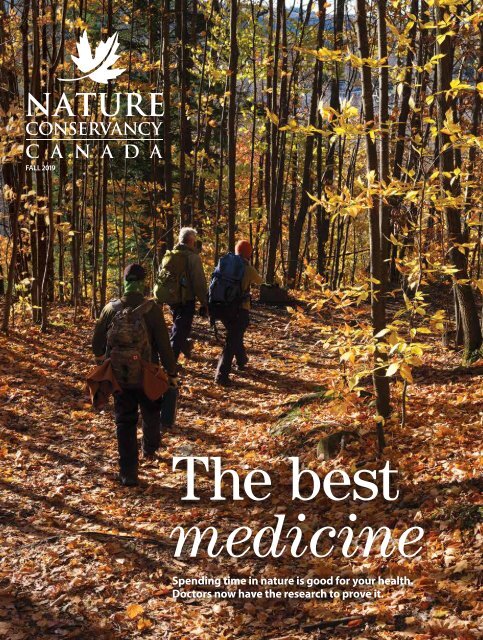

FALL <strong>2019</strong><br />

The best<br />

medicine<br />

Spending time in nature is good for your health.<br />

Doctors now have the research to prove it.

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

245 Eglinton Ave. East, Suite 410<br />

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 3J1<br />

magazine@natureconservancy.ca<br />

Phone: 416.932.3202<br />

Toll-free: 877.231.3552<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>) is the nation’s leading land<br />

conservation organization, working<br />

to protect our most important natural<br />

areas and the species they sustain.<br />

Since 1962, <strong>NCC</strong> and its partners have<br />

helped to protect 14 million hectares<br />

(35 million acres),<br />

coast to coast to coast.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong> is distributed to donors and<br />

supporters of <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

TM<br />

Trademarks owned by the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada.<br />

FSC is not responsible<br />

for any calculations on<br />

saving resources by<br />

choosing this paper.<br />

Printed on Rolland Opaque paper,<br />

which contains 30% post-consumer<br />

fibre, is EcoLogo, Processed Chlorine<br />

Free certified and manufactured in<br />

Canada by Rolland using biogas energy.<br />

Printed in Canada with vegetable-based<br />

inks by Warrens Waterless Printing.<br />

This publication saved 29 trees and<br />

104,292 litres of water*.<br />

COVER<br />

Hikers on <strong>NCC</strong>’s Alfred-Kelly Nature<br />

Reserve, a Nature Destination in Quebec.<br />

Photo by Guillaume Simoneau.<br />

THIS PAGE<br />

Fundy National Park, New Brunswick.<br />

Photo by Zack Metcalfe.<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

GENERATED BY: CALCULATEUR.ROLLANDINC.COM<br />

*<br />

2 FAL <strong>2019</strong> natureconservancy.ca

FALL <strong>2019</strong><br />

CONTENTS<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

Dear friend,<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

For most Canadians, the concept of a hectare may<br />

seem vague. So what would it mean if I told you that,<br />

based on a recent accounting of the total lands you<br />

have helped us conserve since 1962, our total came<br />

in at 14 million hectares (35 million acres)? That’s<br />

a big number!<br />

And how big is 14 million hectares? If you think of<br />

Canada’s geography, it’s about 25 times the size of<br />

PEI, or about four times the size of Vancouver Island.<br />

Describing those hectares in this way makes our collective<br />

efforts to conserve our country’s natural legacy<br />

much more understandable, and something in which<br />

you, as donors and partners, should take great pride.<br />

Thank you.<br />

If you’ve been a supporter of the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) for some time, you may note that<br />

this represents a significant boost in our tally of total<br />

land conserved. But we didn’t get there overnight.<br />

Every number of years, <strong>NCC</strong> undertakes a review of<br />

how we measure our conservation impact. This time<br />

we more fully accounted for the lands we have directly<br />

acquired, conserved and currently steward, as well as<br />

the broader impact of our work through partnership.<br />

Your support has meant that the past several years<br />

have seen an unprecedented increase in the pace of<br />

our work, particularly in large landscape-scale projects.<br />

This includes our work to help relinquish private<br />

rights in lands (such as timber, oil and gas), thereby<br />

removing impediments to conservation. In particular,<br />

we now count the Birch River Wildland Provincial Park<br />

in Alberta (contributing to the world’s largest boreal<br />

forest protected area) and the new Tallurutiup Imanga<br />

National Marine Conservation Area in Nunavut (Canada’s<br />

largest protected area) among major projects<br />

that have benefited from our work to remove private<br />

resource rights.<br />

And so I’m sharing with you 14-million reasons to<br />

feel good about nature.<br />

Nature makes us all feel good, and in this issue of<br />

our magazine, you’ll read about why more doctors than<br />

ever before are prescribing time in nature to improve<br />

their patients’ well-being. And thanks to your belief in<br />

our mission, there are now more places for Canadians<br />

to connect with nature and boost their health.<br />

Thank you for your support of our mission,<br />

John Lounds<br />

John Lounds<br />

President<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

8<br />

14 16<br />

14 Back from the brink<br />

Learn how the Nature Conservancy of Canada is helping bring back species<br />

at risk of extinction.<br />

6 Ralph Wang Trail<br />

Immerse yourself in the diversity of Canada’s endangered native prairie<br />

habitat with a walk down the trail at this Nature Destination in Manitoba.<br />

7 Paddle on<br />

Former Ottawa Riverkeeper Meredith Brown explores Canada’s lakes and<br />

rivers with her handmade whitewater paddle.<br />

8 Prescribing nature<br />

For the sake of a healthy and sustainable future, time in nature is essential.<br />

Doctors now have the research to prove it.<br />

12 Greater sage-grouse<br />

Learn about a bird whose courtship dance is one of North America’s most<br />

incredible wildlife spectacles.<br />

14 Project updates<br />

Listening for the bat signal in Saskatchewan; Making Darkwoods whole in BC;<br />

PEI nature reserve donated by local family.<br />

16 Birds of a feather<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada’s newly appointed Weston Family senior<br />

scientist, Ryan Norris, discusses how you can get involved in conservation.<br />

18 Stories, snakes and sons<br />

Looking back on many visits to Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park in Alberta.<br />

FALL <strong>2019</strong> 3

COAST TO<br />

COAST<br />

Back<br />

from<br />

the<br />

brink<br />

The Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada’s restoration<br />

work is helping protect<br />

endangered species and<br />

is even bringing back<br />

species at risk of extinction<br />

In May of this year, the United Nations<br />

released a Global Assessment Report on<br />

the outlook for species biodiversity worldwide.<br />

This report found that up to one million<br />

unique species are at risk of extinction due to<br />

human-related effects, such as climate change<br />

and habitat loss. The truth is, we are losing<br />

species at an alarming rate, and every day<br />

species are put at risk of disappearing from<br />

the Earth forever.<br />

That’s where you and the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) come in. Efforts to conserve<br />

and restore animal and plant populations in the<br />

wild are an ongoing and important part of our<br />

conservation strategy. And while addressing<br />

the underlying causes for population decline is<br />

a crucial step, we need more habitat protection<br />

and restoration to bring these species back from<br />

the brink of extinction.<br />

Wildlife conservation efforts can take many<br />

forms — from captive breeding programs designed<br />

to boost populations to the restoration<br />

and protection of key habitats. Across Canada,<br />

species at risk are struggling to cope with the<br />

loss of native habitats, invasive species and<br />

rapidly changing climate patterns. But dedicated<br />

conservationists are working hard to restore<br />

populations and protect species biodiversity.<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

KEN GILLESPIE PHOTOGRAPHY/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO.<br />

4 FALL <strong>2019</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Here are six species at risk<br />

that <strong>NCC</strong> is helping to conserve<br />

Piping plover<br />

Blanding’s turtle<br />

American badger<br />

In Atlantic Canada, piping plovers nest<br />

only on sand and pebble beaches with<br />

scattered vegetation. These endangered<br />

birds require peace and quiet<br />

away from human disturbance to raise<br />

their young. In Nova Scotia, the birds<br />

breed on fewer than 30 beaches in<br />

total, and the distribution of suitable<br />

habitat is similarly sparse throughout<br />

the rest of Atlantic Canada. <strong>NCC</strong> has<br />

partnered with provincial governments,<br />

Bird Studies Canada, the Island Nature<br />

Trust, Nature NB, Intervale and other<br />

conservation organizations to identify<br />

and protect piping plover nesting<br />

beaches and clean up shoreline<br />

habitat in the Atlantic region.<br />

Blanding’s turtle is considered<br />

endangered throughout its Great<br />

Lakes and St. Lawrence ranges.<br />

In these areas, road mortality is<br />

among the biggest threats to its<br />

survival. <strong>NCC</strong> conservationists are<br />

actively engaging with the public to<br />

teach drivers how to safely stop and<br />

help turtles cross the road. With new<br />

tools such as carapace.ca, a website<br />

developed by <strong>NCC</strong> and the Province<br />

of Quebec, anyone can snap a picture<br />

of a turtle they see on the road<br />

and contribute to a citizen<br />

science database.<br />

In 2004, <strong>NCC</strong> biologists working on<br />

the Kootenay River Ranch property<br />

in central British Columbia discovered<br />

the presence of endangered<br />

American badgers. The 1,250-hectare<br />

(3,089-acre) stretch of the Upper<br />

Columbia River Valley offers<br />

a continuous grassland habitat free<br />

of roads and other human development,<br />

which so often disturb and<br />

create human-animal conflict for<br />

badger populations. This protected<br />

natural area also provides scientists<br />

with the opportunity to conduct<br />

ongoing research on the endangered<br />

species to further improve<br />

restoration efforts.<br />

SWIFT FOX: CREDIT: ROBERT HARDING/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO. ALL OTHERS: ROBERT MCCAW.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

Monarch<br />

The global population of monarchs<br />

has been decreasing at a rapid rate.<br />

This is thought to be a result of habitat<br />

loss in both its wintering ground in<br />

Mexico and throughout its summer<br />

ranges in Canada and the U.S. <strong>NCC</strong> is<br />

working to restore breeding, feeding<br />

and stopover habitats across the<br />

country and is actively planting<br />

milkweed (the monarch caterpillar’s<br />

host plant) and other native wildflowers<br />

in Manitoba to improve and<br />

expand feeding and breeding habitat<br />

throughout the province. On Pelee<br />

Island in Ontario, we are restoring<br />

wetland and meadow habitat for rare<br />

and at-risk species, such as monarchs.<br />

Swift fox<br />

The swift fox represents an amazing<br />

conservation success story. Although<br />

the species was once extirpated<br />

(locally extinct) in Canada due<br />

primarily to habitat loss, in 1973<br />

a reintroduction program was<br />

launched that has seen a return of<br />

approximately 650 swift foxes to the<br />

Prairies of Alberta and Saskatchewan.<br />

As the species still faces threats from<br />

genetic isolation due to habitat<br />

fragmentation, <strong>NCC</strong>’s work to secure<br />

and steward the remaining grassland<br />

habitat that serves as linkages<br />

between the populations is vital.<br />

Plains bison<br />

An icon of the Prairies, the plains<br />

bison once thundered across much<br />

of western North America, but by the<br />

turn of the 20 th century overhunting<br />

had reduced the total population to<br />

as few as 300 individuals. Since being<br />

reintroduced to Saskatchewan’s Old<br />

Man on His Back Prairie and Heritage<br />

Conservation Area in 2003, <strong>NCC</strong> has<br />

maintained a herd of genetically<br />

pure bison on the property. <strong>NCC</strong> staff<br />

now manage the grassland prairie<br />

for grazing and keep a close eye on<br />

the health of the population.<br />

FALL <strong>2019</strong> 5

BOOTS ON<br />

THE TRAIL<br />

Burrowing owl<br />

Ralph Wang Trail<br />

Immerse yourself in the diversity of Canada’s endangered<br />

native prairie habitat at this Nature Destination in Manitoba<br />

The Ralph Wang Trail, located near<br />

Pierson, Manitoba, provides a glimpse<br />

into the past, when native prairie once<br />

stretched beyond the horizon. Today, grasslands<br />

like this are rare, as are many of the birds<br />

and plants you’ll encounter along the trail.<br />

Grasslands such as those around the<br />

Ralph Wang Trail have long been synonymous<br />

with Canada’s Prairie provinces. They provide<br />

critical stopovers for migratory birds and habitat<br />

for waterfowl and rare and endangered<br />

species, including ferruginous hawk, burrowing<br />

owl and prairie butterflies. Grasslands also<br />

protect our water, sequester and store carbon<br />

and provide a precious and sustainable source<br />

of grazing land for livestock.<br />

The Ralph Wang Trail is also a travel corridor<br />

for wildlife and makes for a good place to<br />

see deer, fox, coyote and other animals. The<br />

eastern cottonwood trees provide an oasis<br />

for songbirds, while the prairie is home to<br />

a variety of rare grassland birds.<br />

HABITAT<br />

Along the trail, the land transitions between<br />

the uplands of native mixed-grass prairie and<br />

the wet meadows of the lowlands. As the trail<br />

moves closer to the water, the vegetation<br />

changes from grasses and wildflowers to<br />

willows, sedges and prairie cordgrass.<br />

Mixed-grass prairie surrounding the trail<br />

may at first look like a field of knee-high<br />

grass, but upon closer inspection you can’t<br />

help but notice its diversity. When the snow<br />

melts, the prairie comes alive with a colourful<br />

variety of grasses and wildflowers, including<br />

a combination of drought-tolerant short-grass<br />

prairie plants and tall grass prairie plants that<br />

grow in moist soils.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>. BURROWING OWL: ROBERT MCCAW.<br />

6 FALL <strong>2019</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Ferruginous hawk<br />

BACKPACK<br />

ESSENTIALS<br />

SPECIES TO SPOT<br />

• burrowing owl<br />

• chestnut-collared<br />

longspur<br />

• ferruginous hawk<br />

• grasshopper sparrow<br />

• LeConte’s sparrow<br />

• loggerhead shrike<br />

• monarch<br />

• moose<br />

• mule deer<br />

• sharp-tailed grouse<br />

• Sprague’s pipit<br />

FERRUGINOUS HAWK: ROBERT MCCAW. PORTRAIT: JESSICA DEEKS.<br />

COMMUNITY EFFORT<br />

In 2012, the Regional Municipality of Edward<br />

(now the Municipality of Two Borders)<br />

entered into an agreement with the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) to ensure the<br />

ongoing protection of the prairie. Though<br />

the land remains municipally owned, a conservation<br />

agreement places certain restrictions<br />

on development.<br />

For almost 40 years, Ralph Wang was the<br />

reeve of the Regional Municipality of Edward.<br />

An amateur birdwatcher and with a lifelong<br />

interest in conservation, Wang worked<br />

with <strong>NCC</strong>’s Manitoba Region to set up a<br />

conservation agreement on land owned by<br />

the municipality.<br />

This area is protected and managed by<br />

the Municipality of Two Borders in cooperation<br />

with <strong>NCC</strong> and a local cattle producer.<br />

SEASON<br />

April 15 to November 15<br />

TRAIL<br />

Type: loop Difficulty: easy<br />

Round-trip distance: 1 km<br />

Surface: mowed grass<br />

DIRECTIONS<br />

From Pierson, drive west on Highway 3 for<br />

1.6 kilometres. Turn south (left) on Antler<br />

Road and proceed for 8.8 kilometres. The<br />

Ralph Wang Trail will be on the east (left)<br />

side of the road.1<br />

Nature Destinations<br />

Learn more at naturedestinations.ca<br />

Paddle on<br />

Former Ottawa Riverkeeper Meredith Brown explores<br />

Canada’s wilderness by navigating its lakes and rivers<br />

with her handmade whitewater paddle<br />

When you live in the world’s largest freshwater ecosystem, [the Great<br />

Lakes basin], you learn how to paddle! My favourite way to explore our<br />

Canadian wilderness is through the endless network of lakes and rivers<br />

that ultimately connect us to our neighbours and to our oceans. As rivers carve their<br />

path across the landscape, they meander and create patterns of rapids and pools.<br />

The rapids are my favourite — for the sounds, the earthy smell and the challenge of<br />

making it down the hydraulic patterns caused by river rocks and elevation changes.<br />

For navigating rivers, I travel by canoe with my handmade whitewater paddle. It<br />

was made using sustainably harvested, local wood by my friend Andy Convery, who<br />

is an artist, educator, canoe builder, paddle maker and wilderness guide. The paddle<br />

was a gift from my husband, Ronnie, who I also love to bring into nature with me.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

FALL <strong>2019</strong> 7

<strong>Fall</strong> at <strong>NCC</strong>’s Alfred-Kelly Nature Reserve,<br />

a Nature Destination in Quebec<br />

BY Zack Metcalfe, author and freelance writer<br />

Prescribing<br />

For the sake of a healthy and sustainable future, time in nature is essential.<br />

Doctors now have the research to prove it.<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

8 FALL <strong>2019</strong> natureconservancy.ca

GUILLAUME SIMONEAU<br />

It was too cold even for insects.<br />

The glassy surface of Lake Superior<br />

faithfully reflected a ruby sky as<br />

the sun rose over Ontario’s Pancake<br />

Bay Provincial Park, crisp beams<br />

of light cutting through the branches of oldgrowth<br />

maple, birch, oak, spruce and pine. The<br />

mist burned away, and birdsong swelled to<br />

fill the open chambers of this lakeside wood.<br />

I was alone.<br />

A week on the road, living out of my car<br />

and hastily erected tents, had me wound<br />

pretty tight, but here I felt calm for the first<br />

time in days, even exultant.<br />

While I wasn’t aware of it in the moment,<br />

the natural cathedral in which I stood was orchestrating<br />

profound changes in me, lowering<br />

my blood pressure and heart rate, and stemming<br />

the flow of the stress hormone cortisol.<br />

My anxieties, tribulations and ruminations<br />

were dissipating while feelings of happiness,<br />

curiosity, vitality and awe were welling up.<br />

The health benefits of time in nature,<br />

once the stuff of folk wisdom, are now the<br />

subject of medical interest. Among children,<br />

regular doses of nature have the long-term<br />

benefits of improved self-esteem, vision,<br />

body weight, attention and overall academic<br />

performance. In surgical recovery rooms,<br />

patients with windows overlooking greenery<br />

are less dependent on painkillers. Having 10<br />

more trees on your city block improves selfperceived<br />

health, equivalent to being seven<br />

years younger, or $10,000 a year richer.<br />

These findings and others are no longer<br />

theoretical, speaking to a phenomenon as<br />

powerful as it is mysterious.<br />

Continued, next page >><br />

nature<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

FALL <strong>2019</strong> 9

Students at Trent University explore<br />

the school’s natural areas and<br />

conduct research on the benefits<br />

of time in nature.<br />

Relatedness<br />

Lisa Nisbet, associate professor at Trent<br />

University’s department of psychology in<br />

Ontario, has focused her career on this<br />

subject. While we walked the edge of campus<br />

in early June, she expounded on the benefits<br />

of even 15 minutes in natural settings.<br />

Nisbet’s research has focused on how time<br />

in nature influences our treatment of nature,<br />

examining what she calls nature relatedness.<br />

In simple terms, nature relatedness is how<br />

much a person appreciates nature as a whole<br />

— not just the cute or scenic parts — and to<br />

what extent they understand the complex relationships<br />

tying it all together. Holding<br />

swamps and sunny beaches in equal regard for<br />

their unique diversity means you’re on the<br />

right track. Regarding yourself as a small piece<br />

of an enormous ecological puzzle, better still.<br />

To determine a person’s level of relatedness,<br />

Nisbet and her colleagues established<br />

the Nature Relatedness Scale: a test of 21<br />

items, which gives a score between 1 and 5,<br />

with 1 representing poor nature relatedness.<br />

To date, this scale has been translated into<br />

over a dozen languages, adopted by a number<br />

of environmental organizations (including the<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada [<strong>NCC</strong>] with its<br />

Nature Quiz program – naturequiz.ca), and<br />

applied to over 10,000 people, from office<br />

workers to conservation professionals. The<br />

average Canadian scores around three on<br />

the Nature Relatedness Scale.<br />

What Nisbet found is that the more time<br />

people spend in nature, the higher their nature<br />

relatedness tends to be, and the more<br />

We all know that when we go out into<br />

nature, we feel calmer, less stressed,<br />

happier, but now we have numbers to<br />

back these feelings up.<br />

likely they are to engage in environmentally<br />

conscious behaviours. And the more time we<br />

spend in nature, the more likely we are to<br />

want to protect it.<br />

“It’s very difficult for the average person to<br />

be an environmental citizen unless they have<br />

an intrinsic motivation to protect nature,” she<br />

explains. “If you don’t see or understand the<br />

consequences of pouring paint down the drain<br />

or putting pesticides on your lawn, you’re just<br />

not going to take the appropriate action.”<br />

“We need to make nature a habit,” she adds.<br />

Best medicine<br />

Ten years ago, Dr. Melissa Lem wrote her first<br />

prescription for nature to a young man battling<br />

attention deficit disorder. She was confident<br />

in the demonstrated benefits, but was<br />

still hesitant to prescribe something so radically<br />

new, fearing it would sound “crunchy<br />

granola.” All the same, it was well-received.<br />

Since then, she’s become an advocate<br />

for nature prescriptions, championing them<br />

at conferences, during guided tours through<br />

the provincial parks of BC and in her family<br />

medicine practice. Lem prescribes time in<br />

nature for depression, stress, attention<br />

disorders, even concussions; 30 minutes<br />

a pop, two hours a week, minimum.<br />

“We all know that when we go out into<br />

nature, we feel calmer, less stressed, happier,<br />

but now we have numbers to back these feelings<br />

up,” she says.<br />

Lem sits on the board of the Canadian<br />

Association of Physicians for the Environment<br />

(cape.ca), an organization whose mission is to<br />

better human health through environmental protection.<br />

It’s thanks to doctors such as Lem that<br />

such things will eventually find their way into<br />

medical textbooks, and that green prescriptions<br />

will become commonplace in medical clinics.<br />

“Doctors and nurses are consistently rated<br />

among the five most trusted professionals<br />

in Canada,” Lem says. “When we say something,<br />

patients listen. If we could get health<br />

professionals to mobilize and prescribe nature<br />

more frequently, I think that would be<br />

quite powerful.”<br />

Just such an endeavour is brewing at the<br />

South Georgian Bay Community Health<br />

TAYLOR ROADES.<br />

10 FALL <strong>2019</strong> natureconservancy.ca

TAYLOR ROADES.<br />

Centre, near Wasaga Beach, Ontario. Ruth<br />

McArthur is a nurse with the District Health<br />

Authority and board member of the Wasaga<br />

Beach Healthy Community Network, the<br />

group ultimately responsible for crafting<br />

these prescriptions. McArthur says the<br />

size and scope of the program is fundingdependent,<br />

but she and her colleagues<br />

expect to be able to write their first<br />

prescriptions sometime this fall.<br />

As they have thus far been imagined, these<br />

prescriptions will come hand-in-hand with<br />

maps of accessible parks near Wasaga Beach,<br />

and perhaps park passes from Ontario Parks<br />

(who is a partner with the health network).<br />

The group hopes to raise awareness among<br />

health centre clients and other health care<br />

practitioners about the benefits of spending<br />

time in nature.<br />

Coming home<br />

In July, I met Tyler Coady, a young man of 33,<br />

strong and very well-spoken, who greeted me<br />

with a joke and a smile in downtown Charlottetown,<br />

PEI. Coady suffers from post-traumatic<br />

stress disorder (PTSD) — the consequence<br />

of a roadside bomb he encountered<br />

during his military service in Afghanistan.<br />

“One of the things I missed the most being<br />

overseas was green space,” says Coady.<br />

“PTSD disrupts pretty well every aspect of<br />

your life,” he explains. It’s plagued him with<br />

unwelcome flashbacks and constant, crippling<br />

anxiety. Coady initially withdrew from society.<br />

Counseling, medication and peer support<br />

were integral to his ongoing recovery, but so<br />

was his purchase of a small farm and regular<br />

hikes through its wilder corners.<br />

While in busy areas, Coady must actively<br />

suppress his PTSD symptoms. When he’s in<br />

nature, however, staying calm is no work at all.<br />

Whatever hold nature has on the human mind,<br />

it’s especially pronounced in people like Coady.<br />

Making use of a master’s degree in military<br />

psychology, he’s been coordinating peer support<br />

groups for other Island veterans with mental<br />

injuries, helping them find peace in nature.<br />

The Island Nature Trust, a valued <strong>NCC</strong><br />

partner, is among the oldest private land trusts<br />

in Canada, protecting over 1,600 hectares<br />

(over 4,000 acres) of PEI wilderness since its<br />

founding in 1979. Recognizing the special<br />

need among veterans for nature, they offered<br />

Coady the use of their largest protected<br />

area — replete with forests, wetlands, trails<br />

and old access roads for those struggling<br />

with mobility.<br />

“There is broad recognition now that we’re<br />

only going to protect what we love. Trying<br />

to compartmentalize people and the rest of<br />

nature doesn’t work,” says Megan Harris,<br />

executive director of the Island Nature<br />

Trust. “We are not separate from nature,<br />

and there are things we need in nature.<br />

Those needs are sometimes compounded<br />

when our minds have been tested in the<br />

extreme, as with veterans.”<br />

Nature For All<br />

For its part, <strong>NCC</strong> has created a number<br />

of programs to increase the connections between<br />

people and nature. Its Conservation<br />

Volunteers program empowers Canadians to<br />

participate in hands-on conservation, restoration<br />

and research on their properties across<br />

the country. <strong>NCC</strong> also has close to 40 Nature<br />

Destinations (naturedestinations.ca), which<br />

offer access to a suite of properties ready to<br />

receive the eager hiker, amateur birder or<br />

nature novice.<br />

“We’re pleased to share these select sites<br />

to help Canadians of all levels of ability and<br />

experience to connect with nature,” said<br />

Erica Thompson, <strong>NCC</strong>’s director of engagement.<br />

“The ‘great outdoors’ brings families<br />

and friends together, and can provide a<br />

greater personal appreciation of nature and<br />

the importance of caring for these special<br />

places. My recent visit to the Gaspé Peninsula,<br />

Quebec, including <strong>NCC</strong>’s Nature Destination<br />

at Pointe Saint-Pierre, reconfirmed to me<br />

the importance of spending time in nature,<br />

unplugging from all devices and celebrating<br />

the curiosity and inspiration that comes<br />

from time well-spent outside.”<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is encouraging people to explore<br />

its Nature Destinations, both on the ground<br />

and online, in all 10 provinces. Visitors can<br />

experience a variety of activities, including<br />

hiking, walking, canoeing, kayaking, photography<br />

and wildlife appreciation. From<br />

Victoria to St. John’s, there are a blend of<br />

natural areas that are accessible in both<br />

urban and rural areas for people to take<br />

advantage of.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> has several goals with its Nature<br />

Destinations program. It hopes to get people<br />

outside so they can enjoy the physical and<br />

mental health benefits of being active in<br />

nature. <strong>NCC</strong> also hopes that people will gain<br />

an appreciation for the ecological benefits<br />

that nature offers, such as clean air and<br />

water, and the importance of conserving<br />

nature for future generations.<br />

From indoor enthusiasts to nature lovers<br />

and everyone in between, <strong>NCC</strong> wants to<br />

make the outdoors more accessible to people.<br />

In preparation for going to one of the<br />

Nature Destinations, people are also encouraged<br />

to visit naturequiz.ca and take the<br />

six-question online Nature Quiz and receive<br />

a Nature Score, which will show how connected<br />

they are to nature. Once people<br />

receive their Nature Score, they can sign<br />

up for a virtual Nature Coach, and receive<br />

email tips for a happier, healthier life by<br />

incorporating time in the outdoors.<br />

Thompson is also a member of<br />

#NatureForAll Canada, an initiative of the<br />

International Union for Conservation of<br />

Nature, aimed at reconnecting humans with<br />

what remains of our natural heritage. The<br />

Canadian chapter is a young but growing<br />

coalition of NGOs, government departments,<br />

academics and of course <strong>NCC</strong>, bringing<br />

a diversity of disciplines to bear on this<br />

campaign of reconnection.<br />

The separation of human beings from<br />

nature has done monumental harm to mind,<br />

body and biodiversity; a point made only<br />

too clear by the people in this article. For<br />

the sake of a healthy and sustainable future,<br />

through these programs and others, finding<br />

ways to pursue nature is not just helping nature,<br />

it’s helping ourselves. Since that early<br />

morning in Pancake Bay Provincial Park,<br />

I find myself more likely to reach for hiking<br />

shoes than for Aspirin, and far less willing<br />

to spend a beautiful day indoors.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

FALL <strong>2019</strong> 11

SPECIES<br />

PROFILE<br />

Greater<br />

sage-grouse<br />

Learn about a bird whose elaborate courtship dance is<br />

one of North America’s most incredible wildlife spectacles<br />

RICK & NORA BOWERS /ALAMY STOCK PHOTO<br />

12 FALL <strong>2019</strong> natureconservancy.ca

APPEARANCE<br />

The greater sage-grouse is brownish-grey<br />

on top, and its tail is black and white.<br />

Adult males have a white band on a black<br />

breast and a collar of pointed white<br />

feathers, along with a pointed tail. Both<br />

sexes sport a black belly.<br />

Greater sage-grouse<br />

recovery project<br />

Although it was once common across the western prairie, the<br />

population of greater sage-grouse decreased by an estimated<br />

80 per cent over the past 30 years. Today, fewer than 250 wild<br />

greater sage-grouse remain in southeastern Alberta and southwestern<br />

Saskatchewan.<br />

The birds were designated as endangered in Canada under the<br />

Species at Risk Act, primarily due to native grassland habitat loss,<br />

fragmentation and degradation due to oil and gas exploration<br />

and the conversion of grassland to cropland.<br />

RANGE<br />

This species is found in western North<br />

America in areas where sagebrush grows,<br />

including southeastern Alberta and<br />

southwestern Saskatchewan. The bird is<br />

extirpated (locally extinct) from BC.<br />

DANCING GROUNDS<br />

Each spring, greater sage-grouse congregate<br />

in areas called leks. Here, males<br />

display elaborate courtship dances for<br />

females. As the males strut, they inflate<br />

and deflate their throat sacs with a<br />

popping sound, throwing their heads<br />

back, spreading their wings and fanning<br />

out their tails.<br />

SAGEBRUSH<br />

Greater sage-grouse populations are<br />

limited to sagebrush grasslands. In the<br />

summer, sagebrush makes up more than 60<br />

per cent of the adult greater sage-grouse’s<br />

diet, along with flowers and buds from<br />

forbs. In the winter, sagebrush makes up<br />

its entire diet.<br />

HELP OUT<br />

You can help protect habitat for greater<br />

sage-grouse. To find out how, visit<br />

giftsofnature.ca.<br />

In 2014, the federal and provincial governments pledged<br />

funding to help protect greater sage-grouse, enabling the<br />

Calgary Zoo to begin a dedicated conservation breeding<br />

and reintroduction program.<br />

In 2016, the zoo announced the creation of Canada’s first-ever<br />

greater sage-grouse breeding facility: the Snyder-Wilson Family<br />

Greater Sage-Grouse Pavilion. Since then, the zoo has established<br />

a healthy population of 54 sage-grouse that makes up the<br />

conservation breeding flock.<br />

In fall 2018, the Calgary Zoo released 66 birds at two protected<br />

locations. One of the sites, provided by Parks Canada, is in<br />

Grasslands National Park in Saskatchewan. The other is on<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) conservation lands in<br />

southeast Alberta.<br />

The Bell-Sage-Grouse<br />

Legacy Project<br />

Barbara Bell was a caring <strong>NCC</strong> supporter who included a gift to<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> in her Will. It was her wish that this gift contribute to a legacy<br />

for conservation while helping an endangered species to recover.<br />

With this gift, <strong>NCC</strong> has invested in a new conservation site<br />

surrounded by native grassland in prime greater sage-grouse<br />

habitat. This property will be named the Bell-Sage-Grouse<br />

Legacy Project.<br />

Barbara’s legacy will be carefully managed to support <strong>NCC</strong>’s<br />

role in habitat restoration and the ongoing stewardship of this<br />

site and of other vital prairie grassland conservation sites.<br />

The Bell-Sage-Grouse Legacy Project started as an agricultural<br />

field that had not been planted for approximately five years.<br />

In the coming years, <strong>NCC</strong> will undertake the restoration of this<br />

65-hectare (160-acre) parcel of land. This restoration work is<br />

a collaborative effort supported by the Alberta Conservation<br />

Association and Alberta Environment and Parks.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> looks forward to this site becoming an intact parcel of native<br />

prairie that provides continuous habitat for greater sage-grouse<br />

and other native grassland species.<br />

With this investment, the impact of Barbara’s generous support<br />

will be felt across Alberta’s grasslands for generations.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

FALL <strong>2019</strong> 13

PROJECT<br />

UPDATES<br />

1<br />

Listening for bat signals<br />

SASKATCHEWAN<br />

2<br />

1<br />

THANK YOU!<br />

Your support has made these<br />

projects possible. Learn more at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/where-we-work.<br />

Listening for bats in central Saskatchewan.<br />

3<br />

Little brown myotis and northern myotis bats are both listed as endangered<br />

in Canada due to devastating population declines in eastern Canada as<br />

a result of white-nose syndrome, an introduced fungal disease.<br />

The fungus is moving west, but it has not yet been documented in Saskatchewan.<br />

As a result, there is an urgent need to determine the population status of<br />

myotis bats in Saskatchewan, as well as to determine what type of habitats they<br />

are using for different parts of their life cycle.<br />

Through acoustic surveys, the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s (<strong>NCC</strong>’s) Saskatchewan<br />

Region has been working to develop a better understanding of what bat<br />

species are found on our properties — by listening for their calls. Using an ultrasonic<br />

recording device in areas likely to be used by bats (such as waterbodies and forest<br />

trails) <strong>NCC</strong> staff record the bats’ calls as they fly around and forage for insects.<br />

The calls of each species are unique. By reviewing sonograms of the bats’ calls<br />

recorded on each property, we can determine which species are present and how<br />

active they are. To date, we have surveyed eight properties across the province<br />

and documented all eight bat species known to occur in Saskatchewan, including<br />

endangered little brown myotis and northern myotis.<br />

In summer 2018, we initiated a project to identify where little brown and northern<br />

myotis were using habitat in the aspen and mixed-wood forests of central Saskatchewan.<br />

Both species have been confirmed in the area; however, which areas<br />

and habitat types they are actually using and for what purpose (such as for day<br />

roosting or as a maternity colony) remains unclear. After catching bats with mist<br />

nets, we then attach radio transmitters to them. Bats with transmitters are tracked<br />

back to their roosting areas, which can then be identified.<br />

Both little brown myotis and northern myotis use tree cavities for roost sites,<br />

so the trees being used can be compared to others on the landscape to identify<br />

which trees are used by myotis bats. This information can help <strong>NCC</strong> tailor our<br />

management plans in the areas where these species occur to help with the<br />

species’ protection and recovery.<br />

You can also help by joining Neighbourhood Bat Watch (batwatch.ca), which<br />

aims to document and monitor bat colonies across Canada. The data collected<br />

allows scientists to track bat populations and distribution, and determine if the<br />

populations are stable or growing, or if they are in need of conservation action.<br />

Determining the age of the bat. Adult bats have a fused joint in their wing, while it is absent in<br />

juveniles. Shining a light from behind illuminates the joint and helps distinguish this feature.<br />

SARAH LUDLOW.<br />

14 FALL <strong>2019</strong> natureconservancy.ca

2<br />

Making Darkwoods whole<br />

BRITISH COLUMBIA<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: STEVE OGLE. STEVE OGLE. YAY MEDIA AS/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO. SEAN LANDSMAN.<br />

When <strong>NCC</strong> acquired Darkwoods in 2008, we knew<br />

at the time that this major accomplishment was not<br />

truly complete. As vast as Darkwoods was (spanning<br />

over 550 square kilometres), there was a missing<br />

piece right in the heart of the conservation area.<br />

For Tom Swann, <strong>NCC</strong>’s director of strategic<br />

initiatives and major gifts, this missing piece was<br />

central to the vision of Darkwoods. He believed it<br />

was a question of when, not if, <strong>NCC</strong> would acquire<br />

the unprotected land at the core of this important<br />

conservation area.<br />

“It didn’t matter who we were talking to; as<br />

soon as we put a map of Darkwoods in front of<br />

them, they would immediately point at the hole<br />

in the middle and ask, ‘What’s that? What’s going<br />

to happen to it?’” Tom recalls.<br />

Ten years after the initial conservation of Darkwoods,<br />

the timing fell into place to make it whole,<br />

by filling the “hole” in its centre. The landowners<br />

were ready to sell the property. Thanks to a trusting<br />

relationship built over time with <strong>NCC</strong> staff,<br />

they chose to prioritize a conservation sale over<br />

other options that would have left the land open<br />

to unsustainable development opportunities.<br />

The newly conserved lands encompass most of<br />

the Next Creek watershed, which nurtures pockets<br />

of old-growth inland temperate rainforest and provides crucial habitat for grizzly bear, wolverine, elk,<br />

bull trout and other wildlife. The unique forests found here are sometimes known as snow forests,<br />

because they receive most of their moisture from the snowpack. These snow forests harbour the<br />

highest tree diversity in BC. Notably, like all of Darkwoods, this land represents a stronghold for the<br />

endangered whitebark pine.<br />

“Conserving the Next Creek watershed and expanding the Darkwoods Conservation Area presented<br />

an incredible opportunity to fulfill a conservation vision that started over a decade ago,” says Nancy<br />

Newhouse, <strong>NCC</strong>’s BC regional vice-president. “We are so grateful for all of the people and organizations<br />

who believed in this vision of creating an internationally significant conservation impact.”<br />

Learn more about the people and organizations who helped make this project happen at natureconservancy.ca/bc.<br />

3<br />

PEI nature reserve donated by local family<br />

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND<br />

Thanks to a well-known family on PEI, <strong>NCC</strong> has conserved 91 hectares (226<br />

acres) of rare wetland and hardwood forest in Kingsboro, near Souris. The<br />

site was donated to <strong>NCC</strong> by Camilla MacPhee and her family, in memory of<br />

her late husband, Melvin MacPhee.<br />

At 13, Melvin began working in his parents’ grocery store in Souris, later<br />

called Clover Farm. In the 1980s, he developed a mall in Souris and became<br />

one of the larger local employers. He was widely regarded as a communityminded<br />

business leader. Melvin was inducted into the PEI Business Hall of Fame in 2005, and died in<br />

2010 at the age of 78.<br />

The Camilla and Melvin MacPhee Nature Reserve features a large undisturbed peat bog; a type<br />

of freshwater wetland that is rare on the Island. It also features an older-growth forest of red maple,<br />

sugar maple and yellow birch; a combination of native hardwoods that is no longer common on PEI. The<br />

area provides habitat for eastern wood-pewee, listed under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, as well as<br />

many provincially rare plants, such as herb-Robert and nodding trillium.<br />

Partner<br />

Spotlight<br />

TD Bank Group (TD) is supporting<br />

the Nature Conservancy of<br />

Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) through its<br />

corporate citizenship platform,<br />

The Ready Commitment,<br />

as the presenting sponsor<br />

of NatureTalks.<br />

The NatureTalks Cross-Country<br />

Speaker Series visits cities across<br />

Canada, providing thoughtprovoking<br />

content and discussions<br />

led by a diverse panel of experts.<br />

As presenting sponsor, TD is<br />

supporting a large network of<br />

community leaders and socially<br />

conscious citizens who are coming<br />

together to explore and value<br />

nature as a resource, a source of<br />

inspiration and a place that<br />

sustains life.<br />

Through The Ready Commitment,<br />

TD aspires to use its business,<br />

philanthropy and people to<br />

help elevate the quality of the<br />

environment so that people<br />

and economies can thrive. This<br />

is part of its commitment to<br />

help create a more inclusive<br />

and sustainable tomorrow.<br />

TD and its national foundation,<br />

TD Friends of the Environment<br />

Foundation, have supported <strong>NCC</strong><br />

for over 30 years. From 2012 to<br />

2016, TD and <strong>NCC</strong> worked<br />

together to help protect forested<br />

areas across Canada. TD helped<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> protect more than 16,000<br />

hectares (40,000 acres) in seven of<br />

Canada’s eight forest regions. From<br />

coastal forest in British Columbia,<br />

to boreal forest in Saskatchewan,<br />

to Acadian forest in Nova Scotia,<br />

support from TD has helped <strong>NCC</strong><br />

protect important forested habitats<br />

across all 10 provinces.<br />

To learn more about TD’s<br />

commitment, visit<br />

td.com/vibrantplanet.<br />

natureconservancy.ca

FORCE FOR<br />

NATURE<br />

Birds of<br />

a feather<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada’s newly appointed Weston Family senior<br />

scientist, professor Ryan Norris, discusses how you can get involved in conservation<br />

MIKE FORD.<br />

16 FALL <strong>2019</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Open grassland spans the 80 hectares<br />

(200 acres) of Kent Island, New Brunswick,<br />

neighbouring Grand Manan Island in the<br />

Bay of Fundy. For 12 years each spring, you could<br />

find Ryan Norris on a patch of land occupying just<br />

300 square metres of this quaint island.<br />

ROBERT MCCAW.<br />

“I could stand in the middle of my study site and see ocean on<br />

both sides,” recalls the associate professor in the Department<br />

of Integrative Biology at the University of Guelph in Ontario.<br />

“Sometimes I would see whales go by.”<br />

Norris was there to monitor the island’s population of savannah<br />

sparrows; part of a four-decade-long, ongoing study on the population<br />

ecology of this species, originated by American ornithologist<br />

Nat Wheelwright and now facilitated by Norris and his research lab.<br />

It was here on Kent Island that Norris evolved his understanding of<br />

how migratory birds fit into the country’s larger conservation picture<br />

under the threats of climate change. Based on his research observations,<br />

Norris notes, “We’re losing birds.”<br />

“At the start of my career, I never considered myself a conservation<br />

biologist. Now, ecologists have no choice — we all need to be<br />

conservation biologists,” says Norris. As the climate rapidly changes,<br />

there is no separation between ecology (the study of species and<br />

their relationships with the environment) and conservation biology<br />

(the study of how we save species), he explains. “It’s why I’m here<br />

at the Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>).”<br />

This spring, Norris was appointed <strong>NCC</strong>’s Weston Family senior<br />

scientist. In this role, Norris will apply conservation research to what<br />

is arguably one of the most urgent issues of our time: the protection<br />

of plants and animals and the natural habitats they need to survive.<br />

Norris will also develop and lead the new Weston Family Conservation<br />

Science Fellows Program, which will support conservation<br />

leaders of the future. The program will offer hands-on opportunities<br />

to graduate students who are studying species at risk, invasive<br />

species or effective conservation.<br />

It’s exciting for people at every<br />

level to contribute and be involved<br />

in conservation science.<br />

“I envision this program as a way to develop and mentor the next<br />

generation of ecologists,” Norris explains. “I hope it becomes a global<br />

example for training conservation leaders.”<br />

Norris brings with him his experience as an ecologist and leader<br />

in migratory bird and monarch butterfly research. He started his<br />

research lab at the University of Guelph in 2006 to focus on the effects<br />

of varying seasons on migratory and resident species, such as those<br />

found here in Canada.<br />

An effective science communicator, Norris hopes to shed light on<br />

the impacts of climate change on migratory species.<br />

“The conservation of these species depends on knowing where<br />

they go during migration and how climate change influences their<br />

Savannah sparrow<br />

success in the wild, or lack of thereof,” he<br />

says. “In my position with <strong>NCC</strong>, I hope to<br />

strengthen collaborations with academic<br />

partners, progress our knowledge on species<br />

and use this information to make evidencebased<br />

decisions about how to better conserve<br />

natural spaces across Canada.”<br />

Norris believes everyone can do their<br />

part to help protect habitat and the species<br />

that live there. The opportunities for citizen<br />

scientists to contribute to conservation<br />

efforts in Canada have never been greater.<br />

With apps like eBird and iNaturalist, the<br />

public can submit species observations<br />

to larger databases.<br />

“Public-contributed data is being used for<br />

high-level research. This information adds<br />

to the data that scientists are using to piece<br />

together information about species behaviours,<br />

habitat and migratory patterns,” he states. “It’s<br />

exciting for people at every level to contribute<br />

and be involved in conservation science.”<br />

While he has wrapped up his time on<br />

the Bay of Fundy for now to work on other<br />

research projects, Norris reflects fondly<br />

about his time on Kent Island, both professionally<br />

and personally.<br />

“I watched my daughter grow up on the<br />

island. She was five months old the first time<br />

she visited it. Now she’s six years old. It’s still<br />

one of my favourite places to be. I actually<br />

just got back from there.”1<br />

The Weston Family senior scientist position and the<br />

Weston Family Conservation Science Fellows Program<br />

are both made possible through the generosity of<br />

The W. Garfield Weston Foundation.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

FALL <strong>2019</strong> 17

CLOSE<br />

ENCOUNTERS<br />

Stories, snakes and sons<br />

Chris Fisher, author, filmmaker and television host<br />

NatureTalks<br />

Chris Fisher will be<br />

a speaker at this fall’s<br />

NatureTalks events.<br />

Learn more at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/<br />

naturetalks.<br />

Driving across Alberta’s grasslands, the horizon<br />

reaches about as far as you can see. The land<br />

is flat, stretched taut over the skin of some of<br />

Canada’s best grasslands — which are among the world’s<br />

most endangered ecosystems. Travelling through this<br />

landscape in no way prepares you for your first glimpse of<br />

Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park/Áísínai’pi — a UNESCO<br />

World Heritage site. Dipping over the crest of the Milk<br />

River valley, hoodoos — the sun-bleached bones of the<br />

Prairies — become visible. This is the land of the Blackfoot<br />

people, where petroglyph tablets share stories of<br />

generations and vindicate the park’s inclusion into the<br />

UNESCO club. Just as eroding winds shaped the iconic<br />

pillars of the hoodoos, these curvaceous landforms<br />

have shaped millennia of visions.<br />

Looking back on my many visits to Writing-on-Stone,<br />

I now realize that by getting lost in this hoodoo maze as<br />

a child, I was actually finding something within myself.<br />

By spending time in places like this, the compass of my<br />

life was set to align with birds, bugs and fresh air.<br />

I recently returned to the park with my two young<br />

sons. It was my chance to help them discover something<br />

in this sacred place. Unbeknownst to us, we had<br />

pitched our tent on a highway for reptiles and amphibians.<br />

Bullsnakes, wandering gartersnakes and even a rattlesnake<br />

slithered through our site, between their upcountry<br />

hibernacula and their riverside summer grounds.<br />

Most slithered through uncelebrated, but a couple<br />

provided a showcase. We admired a yearling rattler at<br />

a distance, until it was safely moved by park staff. I later<br />

formalized introductions between my boys (plus a throng<br />

of onlookers) and a bullsnake calmly coiling in my arms.<br />

I shared information with them about the snake; but these<br />

moments are always more about feelings than facts. Feelings<br />

are our memories’ trigger.<br />

I’m proud that my sons continue to react well to every<br />

snake they meet. It’s hard to know whether they remember<br />

anything from their first intimate encounter with that<br />

bullsnake. But such moments crucially inform our character<br />

and the values upon which they are inscribed.1<br />

CORY PROULX.<br />

18 FALL <strong>2019</strong> natureconservancy.ca

What Will We Leave<br />

For Them?<br />

Invest in what matters most<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada's Landmark Campaign is the largest<br />

private conservation fundraising campaign in Canadian history. Reaching<br />

our target of $750 million will mean the completion of 500 conservation<br />

projects from coast to coast to coast, and the protection of the countless<br />

species that depend on this habitat.<br />

Together, we can protect Canada’s natural legacy.<br />

Donate today at LeaveYourLandmark.ca.<br />

Thank you to all of our donors for supporting the Landmark Campaign.<br />

There's still time to get involved; together, we can reach the campaign target.<br />

With your help, we will conserve more land faster, connect more Canadians<br />

to nature and inspire the next generation of conservation leaders.

Leave your<br />

YOUR<br />

VOICES<br />

Landmark<br />

Thank you for your continued support of the Landmark Campaign!<br />

The success of the Landmark Campaign would not be possible<br />

without your support. Together, we have raised over $615 million to<br />

date to conserve more land, connect Canadians to nature and inspire<br />

the next generation of conservation leaders. You have helped to<br />

complete over 400 conservation projects from coast to coast to coast.<br />

Thank you for investing in nature.<br />

82% ACHIEVED<br />

RAISE<br />

$750<br />

MILLION<br />

NATURE CONSERVANCY OF CANADA<br />

245 Eglinton Ave. East, Suite 410, Toronto, ON M4P 3J1<br />

89% ACHIEVED<br />

CONSERVE<br />

500<br />

NEW PROPERTIES<br />

THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT.<br />

Protecting<br />

the landscape<br />

“I received the Spring <strong>2019</strong> issue<br />

of your publication. I am a former<br />

employee of Parks Canada (retired<br />

over six years ago) and still active<br />

in outdoor activities. I’m also a volunteer<br />

with <strong>NCC</strong>, monitoring the MacFarlane Woods<br />

Nature Preserve on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia.<br />

I also, when able, take part in other <strong>NCC</strong> activities on<br />

Cape Breton Island.<br />

“I was surprised and elated to see the article on<br />

the Beaver Hills Biosphere Reserve in Alberta, as I was<br />

an early team member on the Beaver Hills Initiative<br />

(BHI) as a geomatics specialist from Parks Canada. My<br />

work with the BHI included mapping out undisturbed<br />

areas within the boundaries, working with various<br />

working groups within the BHI on planning issues on<br />

how to protect the area.<br />

“Thanks for bringing the BHI, now the Biosphere<br />

Reserve, to people’s attention. I presented papers<br />

nationally and internationally on the BHI and the<br />

work we were doing to protect the landscape. Our<br />

work was recognized widely and copied in such<br />

places as the eastern slopes around Denver, Colorado,<br />

in their planning for land use.<br />

“Keep up the great work across Canada. I will be involved<br />

for as long as my health holds up.”<br />

~ Rod Thompson has been a monthly donor since 2018<br />

SEND US YOUR STORIES! magazine@natureconservancy.ca<br />

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: BRENT CALVER, COSTAL PRODUCTIONS, COURTESY OF ROD THOMPSON.