From the Ground Up - McCain Foods Limited

From the Ground Up - McCain Foods Limited

From the Ground Up - McCain Foods Limited

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

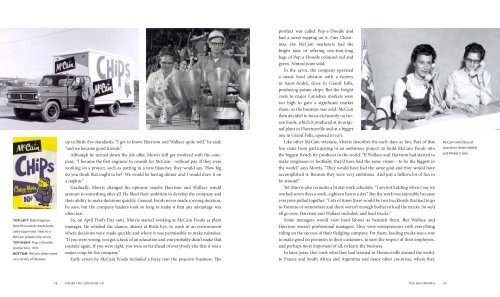

TOP LEFT: Bob Ferguson,<br />

New Brunswick snack foods<br />

sales supervisor, next to a<br />

<strong>McCain</strong> potato-chip truck.<br />

TOP RIGHT: Pop-a-Doodle<br />

production, 1970.<br />

BOTTOm: <strong>McCain</strong> chips came<br />

in a variety of flavours.<br />

up to Birds Eye standards. “I got to know Harrison and Wallace quite well,” he said,<br />

“and we became good friends.”<br />

Although he turned down <strong>the</strong> job offer, Morris still got involved with <strong>the</strong> company.<br />

“I became <strong>the</strong> first engineer to consult for <strong>McCain</strong> – without pay. If <strong>the</strong>y were<br />

working on a project, such as putting in a new blancher, <strong>the</strong>y would say, ‘How big<br />

do you think that ought to be?’ We would be having dinner and I would draw it on<br />

a napkin.”<br />

Gradually, Morris changed his opinion: maybe Harrison and Wallace would<br />

amount to something after all. He liked <strong>the</strong>ir ambition to develop <strong>the</strong> company and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir ability to make decisions quickly. General <strong>Foods</strong> never made a wrong decision,<br />

he says, but <strong>the</strong> company leaders took so long to make it that any advantage was<br />

often lost.<br />

So, on April Fool’s Day 1962, Morris started working at <strong>McCain</strong> <strong>Foods</strong> as plant<br />

manager. He relished <strong>the</strong> chance, absent at Birds Eye, to work in an environment<br />

where decisions were made quickly and where it was permissible to make mistakes.<br />

“If you were wrong, you got a heck of an education and you probably didn’t make that<br />

mistake again. If you were right, you were so far ahead of everybody else that it was a<br />

major coup for <strong>the</strong> company.”<br />

Early errors by <strong>McCain</strong> <strong>Foods</strong> included a foray into <strong>the</strong> popcorn business. The<br />

product was called Pop-a-Doodle and<br />

had a sweet topping on it. One Christmas,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>McCain</strong> marketers had <strong>the</strong><br />

bright idea of offering two-foot-long<br />

bags of Pop-a-Doodle coloured red and<br />

green. Almost none sold.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> 1970s, <strong>the</strong> company operated<br />

a snack food division with a factory<br />

in Saint-André, close to Grand Falls,<br />

producing potato chips. But <strong>the</strong> freight<br />

costs to major Canadian markets were<br />

too high to gain a significant market<br />

share, so <strong>the</strong> business was sold. <strong>McCain</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>n decided to focus exclusively on frozen<br />

foods, which it produced at its original<br />

plant in Florenceville and at a bigger<br />

one in Grand Falls, opened in 1971.<br />

Like o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>McCain</strong> veterans, Morris describes <strong>the</strong> early days as fun. Part of that<br />

fun came from participating in an ambitious project: to build <strong>McCain</strong> <strong>Foods</strong> into<br />

<strong>the</strong> biggest french fry producer in <strong>the</strong> world. “If Wallace and Harrison had started to<br />

make eyeglasses or footballs, <strong>the</strong>y’d have had <strong>the</strong> same vision – to be <strong>the</strong> biggest in<br />

<strong>the</strong> world,” says Morris. “They would have had <strong>the</strong> same goal and <strong>the</strong>y would have<br />

accomplished it. Because <strong>the</strong>y were very ambitious. And just a helluva lot of fun to<br />

be around.”<br />

Yet Morris also recounts a brutal work schedule: “I am not kidding when I say we<br />

worked seven days a week, eighteen hours a day.” But <strong>the</strong> work was enjoyable because<br />

everyone pulled toge<strong>the</strong>r. “Lots of times <strong>the</strong>re would be two truckloads that had to go<br />

to Toronto or somewhere and <strong>the</strong>re weren’t enough bodies to load <strong>the</strong> trucks. So we’d<br />

all go over, Harrison and Wallace included, and load trucks.”<br />

Some managers would view hard labour as beneath <strong>the</strong>m. But Wallace and<br />

Harrison weren’t professional managers. They were entrepreneurs with everything<br />

riding on <strong>the</strong> success of <strong>the</strong>ir fledgling company. For <strong>the</strong>m, loading trucks was a way<br />

to make good on promises to <strong>the</strong>ir customers, to earn <strong>the</strong> respect of <strong>the</strong>ir employees,<br />

and perhaps most important of all, to learn <strong>the</strong> business.<br />

In later years, <strong>the</strong>y took what <strong>the</strong>y had learned in Florenceville around <strong>the</strong> world,<br />

to France and South Africa and Argentina and many o<strong>the</strong>r countries, where <strong>the</strong>y<br />

18 <strong>From</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Ground</strong> up<br />

t he BeG inninG 19<br />

<strong>McCain</strong> switchboard<br />

operators Helen Hallett<br />

and Mabel Carter.