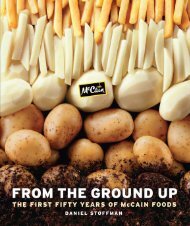

From the Ground Up - McCain Foods Limited

From the Ground Up - McCain Foods Limited

From the Ground Up - McCain Foods Limited

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Michael <strong>McCain</strong>, 1993.<br />

For all its efforts in <strong>the</strong> juice business, <strong>McCain</strong> never<br />

lost sight of its goal to become a big player in french<br />

fries in <strong>the</strong> United States. The original base in nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Maine had distribution advantages, but because of<br />

<strong>the</strong> agronomic limitations of <strong>the</strong> region and <strong>the</strong> processing<br />

technology of <strong>the</strong> time, french fries produced<br />

<strong>the</strong>re weren’t yet up to <strong>the</strong> standards of those produced<br />

in <strong>the</strong> western United States. <strong>McCain</strong>’s first expansion<br />

outside <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast came in 1988 when it acquired<br />

potato baron Pete Taggares’s French fry operations in<br />

O<strong>the</strong>llo, in <strong>the</strong> prime potato-growing area of eastern<br />

Washington State, and in Clark, South Dakota. The following<br />

year, <strong>McCain</strong> spent $35 million to expand <strong>the</strong><br />

O<strong>the</strong>llo plant.<br />

Earlier in 1988, <strong>McCain</strong> had lost out on a chance to<br />

become a major force in french fries overnight when<br />

Lamb Weston was put up for sale by its owner, Amfac. Wallace <strong>McCain</strong>, Tim Bliss,<br />

and Carl Morris toured all <strong>the</strong> Lamb Weston plants and recommended making a bid.<br />

However, Harrison did not think <strong>McCain</strong> had <strong>the</strong> management strength to absorb a<br />

company as big as Lamb Weston. And so, <strong>McCain</strong> did not make a competitive bid for<br />

Lamb Weston, and it went to ConAgra instead.<br />

When Michael took it over in 1991, <strong>the</strong> U.S. business had just absorbed <strong>the</strong> western<br />

U.S. plants bought from Taggares. Michael was eager for more. The industry had added<br />

capacity, causing many competitors to favour volume over profit margins. Michael<br />

and his team proposed acquisitions that would have given <strong>the</strong> company <strong>the</strong> scale and<br />

product portfolio it needed to be competitive. They wanted to buy factories owned<br />

by Nestlé and ano<strong>the</strong>r owned by Universal, which had an excellent assortment of innovative<br />

potato products. But, because of opposition from Harrison, <strong>the</strong>se deals were<br />

not made.<br />

As a result, <strong>McCain</strong> remained largely unknown in <strong>the</strong> United States, struggling to<br />

be profitable. Much of its sales were in <strong>the</strong> lower-priced private-label segments of <strong>the</strong><br />

market. The more profitable premium market was still dominated by <strong>the</strong> big three.<br />

Michael <strong>McCain</strong> summarizes <strong>the</strong> problems in <strong>McCain</strong>’s U.S. potato business at <strong>the</strong><br />

time: “Low scale, no brand, poor product and customer mix, and many operating<br />

problems. Lamb Weston was mauling us in <strong>the</strong> marketplace. It had <strong>the</strong> brand, and it<br />

had a product mix that was giving it enormous advantage. Forty percent of its sales<br />

were in <strong>the</strong> new battered potato products and curly fries, with margins we believed to<br />

be exceeding 40 or 50 percent.”<br />

Lamb Weston was making so much money in <strong>the</strong> specialized segments that it<br />

could afford to be very competitive in pricing to protect its volumes in <strong>the</strong> conventional<br />

segment of <strong>the</strong> french fry market. “It had a classic mix advantage over us,” says<br />

Michael. “Customer mix, product mix, and brand mix.”<br />

Michael <strong>McCain</strong> has a well-deserved reputation as a hard-driving executive<br />

who hates to lose. <strong>From</strong> <strong>McCain</strong>’s U.S. headquarters outside Chicago, he and his<br />

team worked hard to build good relations with his customers. One of those customers<br />

was McDonald’s. Michael established friendly relationships with members<br />

of <strong>the</strong> McDonald’s management team. As Frank van Schaayk observed later, it<br />

was Michael who “turned <strong>the</strong> corner” for <strong>McCain</strong> with McDonald’s for its North<br />

American business.<br />

He also designed <strong>the</strong> landmark Argentina deal with McDonald’s, that Wallace<br />

completed in 1993: an open price calculation with an agreed return on investment for<br />

<strong>McCain</strong> for a period, to entice <strong>McCain</strong> to build a plant in South America. (An open<br />

cost calculation is sometimes agreed to by a buyer and seller for a new product for<br />

which <strong>the</strong>re is no historical cost of production or distribution. In this case, <strong>McCain</strong><br />

required that all its costs plus a pre-agreed profit margin be guaranteed before it<br />

would build a plant. McDonald’s thus had an incentive to buy more because a higher<br />

production volume would reduce <strong>the</strong> cost per unit.)<br />

After almost five years at <strong>the</strong> helm of <strong>the</strong> U.S. business, Michael was fired by<br />

Harrison, in <strong>the</strong> wake of <strong>the</strong> split between <strong>the</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>rs, after which <strong>the</strong> Wallace<br />

<strong>McCain</strong> family acquired Maple Leaf <strong>Foods</strong>. Michael’s new job was as <strong>the</strong> chief<br />

172 f rom <strong>the</strong> <strong>Ground</strong> up<br />

south of <strong>the</strong> border 173<br />

LEFt: Tony Allen (centre) of<br />

Allen and Kidd Farms receives<br />

<strong>the</strong> 2004 <strong>McCain</strong> Idaho<br />

champion potato growers<br />

award; here with Laurie<br />

Jecha-Beard, vice-president of<br />

agriculture for <strong>McCain</strong> <strong>Foods</strong><br />

USA, and Jerry Swisher, field<br />

representative for <strong>McCain</strong><br />

<strong>Foods</strong> USA, in Burley, Idaho.<br />

RIGht: Field manager Doug<br />

Nelson in Basset, Nebraska,<br />

2000.