You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

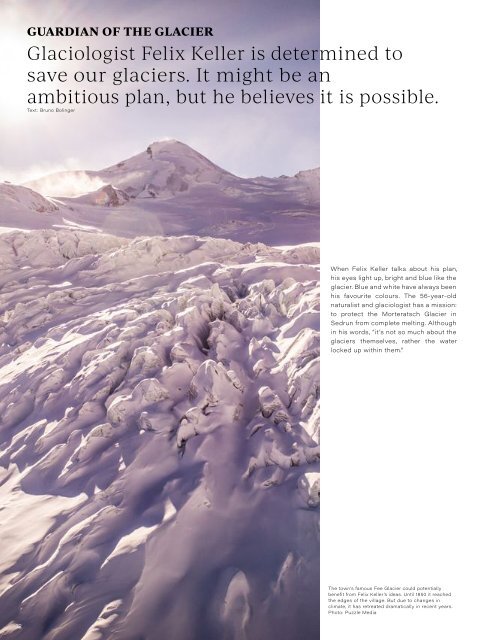

GUARDIAN OF THE GLACIER<br />

Glaciologist Felix Keller is determined to<br />

save our glaciers. It might be an<br />

ambitious plan, but he believes it is possible.<br />

Text: Bruno Bolinger<br />

When Felix Keller talks about his plan,<br />

his eyes light up, bright and blue like the<br />

glacier. Blue and white have always been<br />

his favourite colours. The 56-year-old<br />

naturalist and glaciologist has a mission:<br />

to protect the Morteratsch Glacier in<br />

Sedrun from complete melting. Although<br />

in his words, “it’s not so much about the<br />

glaciers themselves, rather the water<br />

locked up within them.”<br />

In Switzerland, 57 billion cubic metres of water are stored as ice<br />

in its glaciers. And that water is valuable. As the glaciers shrink,<br />

rivers will run lower and lower each year. At present, if the rains fail<br />

in summer, glacial melt prevents the rivers in the valley from drying<br />

up. But once the glaciers are gone, the water supply as we know it<br />

today will cease to function.<br />

Two years ago, Felix Keller was having lunch with his then<br />

supervisor at the Academia Engiadina educational institution in<br />

Samedan. “If you were of any value as a glaciologist, you ought<br />

to save the Morteratsch Glacier,” his supervisor teased. “Forget it,<br />

there’s no way that would work!” was Keller‘s answer at the time.<br />

But he couldn’t get the idea of saving the glacier out of his head.<br />

The very next day while fishing in a wild stream, he began to think<br />

through the possibilities and impossibilities of such an ambitious<br />

project. Glass, metal, plastic and paper – they all get recycled in<br />

this day and age, he thought. So why not the glacial meltwater?<br />

After days of thinking over the facts and turning them over in his<br />

head time and time again, Keller couldn’t find any good grounds<br />

on which to say they wouldn’t be able to successfully rescue the<br />

glacier. So the project was born. The question he found himself<br />

asking was: “Should we try to preserve glaciers as freshwater<br />

storage for future generations?”<br />

Keller presented his idea to friend and fellow glaciologist<br />

Hans Oerlemans from the University of Utrecht. A series of<br />

measurements taken by this university since 1994 makes the<br />

Morteratsch Glacier the world‘s best-studied glacier in terms of<br />

energy balance. Interestingly, Oerlemans, unlike Keller, believed<br />

the plan to be quite feasible. He suggested they could test the<br />

theory by spreading snow produced from the glacier’s meltwater<br />

over part of the glacier itself to protect it from solar radiation.<br />

The projections that followed the experiment were surprising.<br />

If just 10 percent of the glacier‘s surface could be kept snowcapped<br />

during the summer, the glacier would potentially start<br />

growing again within ten years. That would be a dramatic turnaround.<br />

But the numbers in question were enormous. One million<br />

square metres of glacier would have to be covered with metres of<br />

snow. That meant the project would require 30,000 tonnes of snow<br />

to be produced. 30,000 tonnes for each day of the short weather<br />

window between winter and early summer! It would need to be<br />

done in the high mountains and, if possible, without the use of<br />

electricity. Confronted with such a mammoth task, Keller faced<br />

sleepless nights once again.<br />

“If just 10 percent of the glacier’s<br />

surface could be kept snow-capped during the<br />

summer, the glacier would potentially start<br />

growing again within ten years.”<br />

Felix Keller, 56, grew up in Samedan and has three children. He is a co-director<br />

of the European Tourism Institute at the Higher School of Tourism in Samedan. He also<br />

works on various research projects and lectures on the geography of tourism,<br />

resource management, and teaching methods, and conducts international seminars.<br />

Photo: Bruno Bolinger<br />

A passionate violinist, Keller spends half an hour each morning<br />

practising. “My daily violin playing opens up my mind,” he says.<br />

Keller relies on his morning routine to come up with new ideas<br />

and solutions. One example is his plan to produce snow using a<br />

‘Schneelanze’ type snow cannon; it is patented in Switzerland and<br />

works without electricity. It should be possible to spread the snow<br />

using the cable cars that already run over the glacier. Soon, they<br />

hope that funding options will open up, and a working prototype for<br />

the project will be built in cooperation with industrial partners to<br />

prove its practical feasibility.<br />

The estimated cost of the whole project over the next 30<br />

years is 100 million Swiss francs. “That’s only a few million francs<br />

per year,” explains Keller, “even if it prevents just one river drying<br />

out in one of the dry summers we have to come, then it’s a good<br />

investment.” He goes one step further: “I recommend that we<br />

apply our approach to one glacier in each of the catchment areas<br />

supplying the six major rivers in Switzerland as soon as possible.”<br />

The town’s famous Fee Glacier could potentially<br />

benefit from Felix Keller‘s ideas. Until 1850 it reached<br />

the edges of the village. But due to changes in<br />

climate, it has retreated dramatically in recent years.<br />

Photo: Puzzle Media<br />

12<br />

13