Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

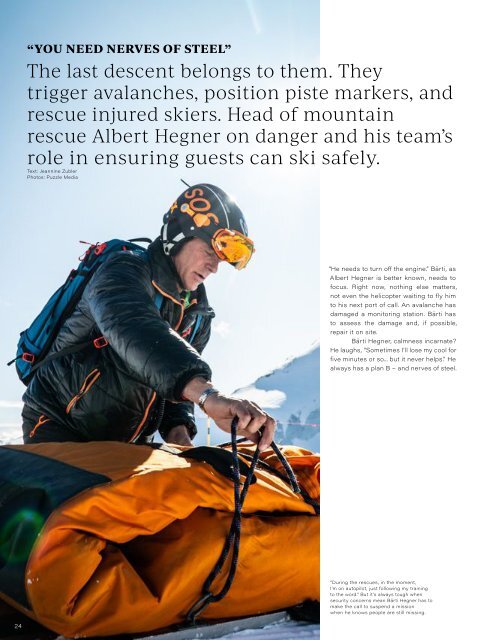

“YOU NEED NERVES OF STEEL”<br />

The last descent belongs to them. They<br />

trigger avalanches, position piste markers, and<br />

rescue injured skiers. Head of mountain<br />

rescue Albert Hegner on danger and his team’s<br />

role in ensuring guests can ski safely.<br />

Text: Jeannine Zubler<br />

Photos: Puzzle Media<br />

“He needs to turn off the engine.” Bärti, as<br />

Albert Hegner is better known, needs to<br />

focus. Right now, nothing else matters,<br />

not even the helicopter waiting to fly him<br />

to his next port of call. An avalanche has<br />

damaged a monitoring station. Bärti has<br />

to assess the damage and, if possible,<br />

repair it on site.<br />

Bärti Hegner, calmness incarnate?<br />

He laughs, “Sometimes I’ll lose my cool for<br />

five minutes or so... but it never helps.” He<br />

always has a plan B – and nerves of steel.<br />

“I always have a plan B”<br />

The ability to stay calm is indispensable in a job where the situation is<br />

constantly changing. And ‘routine’ is an alien concept to Bärti. The one<br />

fixed point in his schedule is at half-past four each morning when he<br />

is always in his office at the valley station. From there, he analyzes the<br />

previous night, and in particular the information collected by his snowcat<br />

drivers. He uses everything at his disposal to estimate the current<br />

avalanche risk and decides whether the ski area will open that day.<br />

The Swiss Avalanche Institute (SLF) makes a general<br />

recommendation for the area which serves as a guide. In addition to<br />

all of that, he sometimes draws on the experiences of his predecessor<br />

Dominik Kalbermatten, who boasts 25 years worth of valuable<br />

knowledge when it comes to assessing the snow situation in the<br />

area. Sometimes, Bärti has to increase the danger level above the<br />

SLF recommendation. As the head of mountain rescue for the high<br />

alpine ski resort Saas-Fee, he has a huge responsibility and faces<br />

several challenging decisions daily. A particular challenge of this ski<br />

resort is that it starts at an altitude where many others end, at 1,800<br />

metres above sea level. The avalanche situation is rarely clear cut.<br />

As the leader of the mountain rescue team, he is responsible for the<br />

safety of the whole area. It would even be his duty to recommend total<br />

evacuation if the avalanche risk were to reach levels that extreme.<br />

He makes these decisions with the support of the Bergbahnen (lift<br />

company) management team as well as the crisis staff at the town hall.<br />

After a heavy snowfall, the ski resort usually stays closed at<br />

the beginning of the day. It remains closed until Bärti and his team<br />

can detonate explosives to trigger controlled avalanches in highrisk<br />

areas, removing dangerous buildups of snow from the steepest<br />

slopes. They usually use a helicopter, or, when there is no other<br />

option, they ski tour and do the job by hand. When it comes to touring,<br />

Bärti needs to carry around 20 kilograms of explosives in his backpack.<br />

Is that not scary? “It‘s heavy,” he says with a wink. Once the<br />

snow loads on the steep slopes have been reduced, the avalanche<br />

Both in Saas-Fee and Saas-Grund there<br />

are glacier slopes. Leaving the pistes<br />

in glacial areas is extremely risky and<br />

re-quires years of experience, training,<br />

and knowledge of crevasse rescue and<br />

how to use ropes effectively. Mountain<br />

guides know the area well and offer ski<br />

and snowboard freeride tours.<br />

Saas-Fee‘s piste patrol works closely with Air Zermatt. For complex rescues in<br />

difficult-to-access terrain, Bärti calls in the helicopter. This is often the case when the<br />

rescue requires heavy equipment.<br />

situation can be reassessed. And when it reaches a reasonable level<br />

of risk, they can reopen the snowsports area. That doesn’t mean the<br />

risk has totally resolved, Bärti emphasises: “You should never lose<br />

your respect for the mountains. Avalanche danger prevails, as long<br />

as there is snow on the ground.”<br />

Crevasses also present a huge risk factor. In the winter they<br />

lie hidden under a sheet of snow. Even Bärti, who knows the area<br />

and its terrain better than most, says that leaving the marked pistes<br />

on the glacier is too dangerous for him. He has witnessed far too<br />

many rescue missions for that. He recalls the time a young snowboarder<br />

fell into a crack below the Allalinhorn. Despite the efficient<br />

rescue effort, the snowboarder later died in the hospital. Such cases<br />

can really affect Bärti and the team. Especially when children are<br />

involved, he reflects, becoming more pensive. “During the rescues, in<br />

“During the rescues, in the moment,<br />

I’m on autopilot, just following my training<br />

to the word.” But it‘s always tough when<br />

security concerns mean Bärti Hegner has to<br />

make the call to suspend a mission<br />

when he knows people are still missing.<br />

saas-fee.ch/bergfuehrer<br />

Avalanche bulletin<br />

Produced by the WSL Institute for Snow<br />

and Avalanche Research SLF, the<br />

bulletin appears twice daily in winter: find<br />

it on slf.ch or the app for smartphones.<br />

“We talk a lot within the team about<br />

the things we experience. Talk,<br />

talk, and talk again, it helps us to<br />

process everything.”<br />

24<br />

25