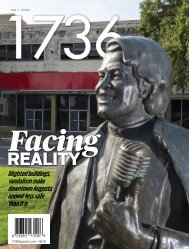

Education Edition - 1736 Magazine, Fall 2019

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

SPIVEY continued from 23<br />

Although Spivey was a Richmond Academy alumnus, he<br />

politely declined the offer. But then the “offer” politely turned<br />

into an order.<br />

So in 2009, a somewhat reluctant Spivey took the helm of a<br />

school that had lost its luster in the 34 years since he roamed<br />

its halls as a senior. But his three years as principal not only<br />

changed the school – it changed Spivey’s life.<br />

“It was the best job I ever had,” said Spivey, who retired<br />

from the school system in 2014 as deputy superintendent.<br />

Although graduation rates, test scores and other performance<br />

metrics increased under his leadership, Spivey<br />

considers his crowning achievement to be restoring the historic<br />

school’s sense of pride, and its decorum.<br />

“The school was out of control,” Spivey said. “They were<br />

having some gang issues, a lot of fighting going on. There just<br />

wasn’t a lot of pride in the school. The teachers were just kind<br />

of down and out.”<br />

Spivey made sweeping changes at the school, relying on a<br />

common-sense based playbook the former physical education<br />

teacher and coach developed during his years in administration,<br />

first as a principal at Tutt Middle School and later as<br />

principal at Westside.<br />

First on the list was restoring order. Spivey got security officers<br />

out of the central office and dispersed them throughout<br />

the three-story building. Then he changed the policy to allow<br />

students to enter the building when they arrived at school -<br />

just like Westside - rather than letting them crowd around the<br />

school’s locked doors.<br />

“You can imagine what it was like not letting them in until<br />

the bell sounded,” Spivey said. “You’ve got 1,300 students<br />

trying to rush the doors.”<br />

Spivey also cut the school’s three lunch periods to two,<br />

eliminated the second period that cut into classroom time. He<br />

reduced lunchroom crowding by implementing an intramural<br />

basketball program, which encouraged many students to eat<br />

faster to play and watch the games. He also had the school’s<br />

former cafeteria, which had been turned into a weight room<br />

during the 1980s, turned into a seniors-only lunchroom, which<br />

dispersed the crowds even more. (The lunchroom was later<br />

renamed The Carl T. Spivey Cafe in his honor.)<br />

He boosted school spirit by replacing damaged trophy cases,<br />

which had been broken during fights, with new cases built<br />

by a friend who was a master carpenter. The cracked tiles at<br />

the school’s main entrance were replaced by floating wood<br />

flooring with the school’s “R” logo prominently painted in<br />

the middle. Against the advice of his colleagues, he allowed a<br />

bonfire to be lighted during homecoming.<br />

“Everybody had a great time, nobody got in trouble,” Spivey<br />

said. “Those are just the little things to kind of restore that high<br />

school atmosphere. It didn’t hurt that the football team was<br />

good and they were winning - that adds a lot of school spirit.<br />

“Football’s the first sport of the year. If it does well, a lot of<br />

kids get on the bandwagon and it makes a lot of difference with<br />

the culture of the school. If (the athletes and cheerleaders) are<br />

not doing well, then other people become the ‘cool’ kids.”<br />

Spivey himself was a high school athlete, getting baseball<br />

scholarships to South Georgia State College and the University<br />

of West Georgia. His first jobs in the school system were<br />

teaching physical education and serving as a coach at several<br />

county schools before moving into administration in 1996 as<br />

assistant principal of Westside High School.<br />

When it came to discipline or counseling students from<br />

disadvantaged backgrounds, Spivey could draw on his own<br />

experiences growing up in Augusta’s blue-collar Harrisburg<br />

neighborhood, which at the time was home to many textile mill<br />

workers, city employees and other working-class families.<br />

His first home was in the Olmstead Homes public housing<br />

project before his father, a firefighter, moved the family to<br />

a home on nearby Lake Avenue. Like many Harrisburg kids,<br />

Spivey attended John Milledge Elementary and Tubman Junior<br />

High, and spent a lot of time at Chafee Park’s pool and gymnasium,<br />

as well as the adjacent Whataburger and the Boys & Girls<br />

Club on Division Street.<br />

“I always thought we were kind of middle class, but as I look<br />

back, we probably were kind of poor,” Spivey recalls. “But our<br />

parents made us go to church on Sunday and taught us good<br />

lessons. The neighborhood people, everybody watched out for<br />

everybody, so I think I learned some good life lessons by being<br />

raised in Harrisburg. I think my older friends would say the<br />

same thing.<br />

“I think being raised in Harrisburg helped me stay<br />

grounded,” he said. “As I became a principal, I could relate<br />

to the kids. At Richmond Academy, we had a very diverse<br />

population. I always felt like I could relate well to all of them<br />

because I knew where I came from.”<br />

Spivey’s biggest contribution to restoring pride in Richmond<br />

Academy was his idea to establish a school “Hall of Fame.” He<br />

came up with the concept after seeing a similar program at a<br />

smaller school while on a cross-state cycling trip with his wife.<br />

With a charter dating back to 1783, Richmond Academy<br />

has produced numerous noteworthy graduates, from former<br />

Supreme Court Justice Joseph R. Lamar to Forrest “Spec”<br />

Towns, Georgia’s first Olympian and first gold medal<br />

recipient.<br />

Spivey and a committee began working on the Hall of Fame<br />

and in 2012 named its first inductees, which included former<br />

Georgia Gov. Carl Sanders, anchorwoman Judy Woodruff and<br />

NCAA Hall of Fame coach Pat Dye. Portraits of inductees hang<br />

in the school’s media room and recipients are recognized at an<br />

awards banquet every October.<br />

“I think it has really helped pull the community back into the<br />

school,” Spivey said.<br />

The Hall of Fame’s bylaws state that at least one inductee<br />

each year be an educator. This year, that educator happens to<br />

be Spivey, who after leaving Richmond Academy served as the<br />

school system’s deputy superintendent as well as its interim<br />

superintendent until his retirement in 2014.<br />

In all his 34 years as an educator and administrator, Spivey<br />

still considers his three years at Richmond Academy as the<br />

high watermark of his career.<br />

“I know that our graduation rates improved and out test<br />

scores improved,” Spivey said. “But the biggest thing that<br />

changed was the atmosphere. That feeling of being able to<br />

enjoy school.”<br />

78 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com<br />

1117_T_78_AM____.indd 78<br />

10/25/<strong>2019</strong> 12:10:01 PM