Anthony Haden-Guest – Louise Nevelson

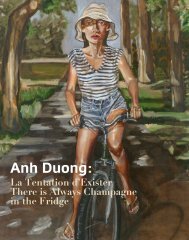

Excerpt from the book “Louise Nevelson – The Way I Think Is Collage”, the first monograph on one of the most important artists of the 20th century to focus on her collage works that spanned her entire career. Published by Galerie Gmurzynska on the occasion of an exhibition at the gallery space in Zurich.

Excerpt from the book “Louise Nevelson – The Way I Think Is Collage”, the first monograph on one of the most important artists of the 20th century to focus on her collage works that spanned her entire career. Published by Galerie Gmurzynska on the occasion of an exhibition at the gallery space in Zurich.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong><br />

The way I think is collage<br />

Texts by<br />

Robert Indiana<br />

Bill Katz<br />

<strong>Anthony</strong> <strong>Haden</strong>-<strong>Guest</strong>

By the time I first laid eyes on Louise<br />

<strong>Nevelson</strong>, which was soon after I arrived<br />

in Manhattan, she had become, to adapt<br />

Norman Mailer’s phrase, an advertisement<br />

for herself. She was not a National Treasure<br />

- that’s a label pinned on individuals,<br />

usually men, whose passions and poisons<br />

have been safely expended in the past -<br />

but a more formidable creature, a Sacred<br />

Monster, seemingly a bit afloat above<br />

mundane reality on the hovercraft of fame.<br />

This, after all, is the woman who announced<br />

during an Avedon shoot for Vogue “When<br />

I’m the star, I never get bored.”<br />

Face to face <strong>Nevelson</strong> could have an<br />

astringent, take-no-prisoners manner but in<br />

the wider world she owed that fame mostly<br />

to her appearance, which is to say the<br />

feathery barricades of dolly-bird eyelash,<br />

the exotic headgear, the clothing which, as<br />

with an Edward Goreyesque grande dame,<br />

veered from the operatic to the Haute Bag<br />

Lady and which might incorporate ethnic<br />

dress, tablecloths, ornaments made out of<br />

detritus, and vintage furs.<br />

The mandarins of the art world who incline<br />

to be suspicious of outré bohemianism - as<br />

when Degas snapped “My dear Whistler,<br />

you have too much talent to behave the way<br />

you do.” - forgave <strong>Nevelson</strong> largely, or so I<br />

would guess, because it was understood that<br />

she was not just a needy eccentric, but that<br />

there was an authentic streak of theater in<br />

her life, as in her work (She hugely admired<br />

Martha Graham).<br />

Edward Allbee, who knew <strong>Nevelson</strong><br />

well, has said that she told “half truths<br />

to most people.” She would give utterly<br />

contradictory reasons for her use of black,<br />

for instance, or for her preference for wood.<br />

Thus when she was 35 she said “I often hear<br />

the remark ‘Oh! If I could be a child again!,’<br />

but somehow, for myself, I am always so<br />

busy living in the present that I never look<br />

back to relive my childhood but more to<br />

search the ‘why and wherefore’ of things of<br />

the present.”<br />

So. That childhood. She was born Louise<br />

Berliawsky in 1899 in Kiev, which was then<br />

Tzarist Russia, and she sailed for America<br />

with her mother at the age of six to join her<br />

father who had gone before, There was a<br />

stop en route at the ship depot in Liverpool.<br />

Of this, she remembered “I can still see<br />

it filled with light, it was a fantasy. There<br />

were many shops that I thought were houses<br />

under one roof that could have been the<br />

heavens. There was a store that sold dolls.<br />

I had never seen a doll and was fascinated<br />

by the eyes. When you laid her down her<br />

eyes closed every time - I marveled at how<br />

unhuman I was because my eyes could<br />

remain open.”<br />

Most Jewish immigrants to the United<br />

States settled in the big cities but the<br />

Berliawskys set up in Rockland, Maine.<br />

There was little of Old Europe’s visceral<br />

anti-Semitism in this rock-ribbed Yankee<br />

community but plenty of un-neighborly<br />

chill. Isaac Berliawsky would ultimately do<br />

well in lumber and as a contractor but at<br />

the beginning he supported his family by<br />

picking bits and pieces he could sell from<br />

the dumps. And little Louise soon became<br />

absorbed in picking up and collecting little<br />

bits and pieces of stuff too.<br />

She was a shy, lonely child in Rockland.<br />

And here let me introduce another lonely<br />

child, Philip Haldane, who appears in The<br />

Magic City, a 1910 children’s book by E.<br />

Nesbit, who Gore Vidal ranked as second<br />

only to Lewis Carroll. Philip, an orphan,<br />

who feels abandoned by his older sister, sets<br />

to building a city on a tabletop.<br />

He was accustomed to the joy that comes<br />

with making things, wrote Nesbit. He<br />

put everything you can think into it; the<br />

dominoes, and the domino box; bricks and<br />

books; cotton-reels that he begged from<br />

Susan, and a collar-box and some cake-tins<br />

contributed by the cook. He made steps of<br />

the dominoes and a terrace of the domino<br />

box. He got bits of southernwood out of<br />

the garden and stuck them on cotton-reels,<br />

which made beautiful pots and they looked<br />

like bay trees in tubs. Brass finger-bowls<br />

17

Page 16<br />

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong>, 1971; Mort Kaye Studios, Inc., photographer;<br />

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> papers, Archives of American Art.<br />

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> in straw hat;<br />

Photographer unknown;<br />

Farnsworth Art Museum <strong>Nevelson</strong> Archive.

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> in sunglasses and fur coat<br />

in front of volcano image; Photographer unknown;<br />

Farnsworth Art Museum <strong>Nevelson</strong> Archive.

served for domes, and the lids of brass<br />

kettles and coffee-pots from the oak dresser<br />

in the hall made minarets of dazzling<br />

splendour. Chessmen were useful for<br />

minarets too.<br />

He worked hard and he worked cleverly,<br />

and as the cities grew in beauty and<br />

interestingness he loved them more and<br />

more. He was happy now. There was no<br />

time to be unhappy in.<br />

I don’t want to be simplistic, just to suggest<br />

that <strong>Nevelson</strong>’s Scavenger Aesthetic, the<br />

urge that drove her to make her sculptures<br />

and these collages, has deep, primal roots,<br />

both formal and romantic. <strong>Nevelson</strong> would<br />

later speak of her life as an immigrant child<br />

amongst the Maine Yankees and she related<br />

it to the fact that she began to see “almost<br />

anything on the street as art.”<br />

Louise met Charles <strong>Nevelson</strong>, a well-to-do<br />

entrepreneur, through her father. She was in<br />

her late teens and had been set on being an<br />

artist since she saw a statue in the Rockland<br />

library when she was nine. <strong>Nevelson</strong> took<br />

her to New York when she was 20. She<br />

stayed in the Martha Washington Hotel for<br />

Women on East 29th and they went to see<br />

the bracingly new Flatiron Building and the<br />

Statue of Liberty. She rhapsodised about<br />

“the water and the sky and this wonderful<br />

oversized thing. It looks like she reaches to<br />

heaven.”<br />

Louise and Charles married in 1918 but<br />

she was increasingly pulled apart by the<br />

demands of home-making and making<br />

art. “I continued my studies, and then my<br />

child was born. The greater restriction of<br />

a family life strangled me, and I ended my<br />

marriage,” she observed flintily. Her child<br />

was a son, Myron. <strong>Nevelson</strong> would earn a<br />

reputation for ruthlessness but her friend<br />

Marjorie Eaton would tell of her obsessive<br />

guilt at her desertion of her family, of her<br />

talking of it incessantly as she painted.<br />

Reading accounts of Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong>’s<br />

development as a young woman artist,<br />

working her way into middle age, is<br />

agonizing, but not quite as agonizing as it<br />

must have been to live, because she was<br />

such a late developer that it is essentially a<br />

long preamble, a bildungsroman, with the<br />

important buildings only popping up in<br />

the last chapters. And, like Mark Rothko,<br />

<strong>Nevelson</strong> would neither forget nor forgive<br />

her years of privation.<br />

An account of her life is also an account of<br />

the art world before the fame, the money.<br />

<strong>Nevelson</strong> joins the Art Students League;<br />

there are squabbles; getting left out of<br />

groups; studying with Frederick Kiesler,<br />

the radical Viennese architect, with Hans<br />

Hofmann and with Baroness Hilda Rebay,<br />

a force behind what was on its way to<br />

becoming the Guggenheim Museum for<br />

Non-Objective Art; and working, although<br />

not as closely as she sometimes liked to<br />

suggest, with the Mexican muralist, Diego<br />

Rivera.<br />

There was her outspokenly active sexlife<br />

- “I love romances and I like to have<br />

affairs” - which included flings with Kiesler<br />

(probably) and Rivera (certainly). And<br />

there are other more unexpected elements,<br />

such as <strong>Nevelson</strong>’s interest in Spiritualism,<br />

Buddhism, dream analysis and the like.<br />

Laura Lisle, author of Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong>: A<br />

Passionate Life, quotes Hans Hoffman’s<br />

observation that “the fourth dimension is<br />

the realm of the spirit and imagination,<br />

of feeling and sensibility,” and notes a<br />

suggestion that the Fourth Dimension is the<br />

unseen fourth wall in Cubism. There’s not<br />

much occult hoopla in the art world these<br />

days. It pursues other gods.<br />

The art world differed in another<br />

substantial way. <strong>Nevelson</strong> struggled for<br />

thirty years, working in near obscurity and<br />

making no sales. She was given a show by<br />

Karl Nierendorf, a dealer from Cologne,<br />

who had opened a gallery close to MOMA<br />

at 20 West 53rd Street. It soon became one<br />

of New York’s best. Her show opened on<br />

September 22, 1940 and got a number of<br />

reviews, mostly favorable.<br />

Nothing sold.<br />

<strong>Nevelson</strong>, who was already drinking<br />

20

heavily, fell into such a depression that she<br />

actually found the daylight painful. Many<br />

good artists were suffering similarly at<br />

the time but <strong>Nevelson</strong> was also a “woman<br />

artist.” Cue magazine reviewed her thus on<br />

October 4 1941: We learned the artist is a<br />

woman, in time to check our enthusiasm.<br />

Had it been otherwise, we might have<br />

hailed these sculptural expressions as by<br />

surely a great figure among moderns. No<br />

wonder <strong>Nevelson</strong> said of this period in a<br />

television interview when she was 78: “You<br />

have blinders like a horse. You don’t look<br />

too much. You have a place to go.”<br />

In 1943 Jimmy Ernst, the son of Max<br />

Ernst, and his partner, Elenore Lust, gave<br />

<strong>Nevelson</strong> a solo show, her third, at New<br />

York’s Norlyst Gallery. It was called The<br />

Circus. That too was excellently received.<br />

Again not one piece sold.<br />

When the work was returned to her studio,<br />

<strong>Nevelson</strong>, who was running short on space,<br />

picked out a few bits and pieces for recycling<br />

into future work, hauled the body<br />

of the show out to the lot behind her Tenth<br />

Street building and burned it.<br />

Success came when <strong>Nevelson</strong> was pushing<br />

sixty. How many hopefuls these days would<br />

give it that long? Then the sales came,<br />

the fame built. Life in 1958 described<br />

her as “A sorceress at her desk.” But her<br />

long-contained rage was always ready to<br />

explode. When Alfred Barr asked her where<br />

she had been all these years, <strong>Nevelson</strong><br />

snapped “Right here in New York, working<br />

- where the hell have you been?” Laura<br />

Lisle relates how she sat at the bar at one of<br />

her openings, in tears, and saying again and<br />

again “It’s too late, it’s much too late.”<br />

Actually, the timing had been absolutely<br />

right. <strong>Nevelson</strong>’s work had always looked<br />

interesting, but seldom seemed wholly<br />

resolved. Only now was she beginning to<br />

produce the unerring series of sculptures<br />

and collages such as these. Only Philip<br />

Guston, fourteen years her junior, comes<br />

to mind as a comparable late bloomer.<br />

And Guston, of course, had been an early<br />

Above<br />

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> with Bill Katz, Marisol, Jasper<br />

Johns, Alfonso Ossorio and Victoria Bar;<br />

Photographer unknown; Farnsworth Art Museum<br />

<strong>Nevelson</strong> Archive.<br />

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong>, Robert Indiana and others,<br />

1973; Diana MacKown, photographer; Louise<br />

<strong>Nevelson</strong> papers, Archives of American Art.<br />

21

loomer also, but producing different<br />

blooms..<br />

There was both luck and happenstance<br />

in <strong>Nevelson</strong>’s blossoming, but it’s the luck<br />

and happenstance that you need to be able<br />

to recognize and make work for you. Lisle<br />

notes that in 1957 Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> got<br />

a crate of liquor as a Christmas present.<br />

She investigated it. In terms of their form<br />

crates were Cubist, and Cubism was her<br />

enduring passion, but it was a Cubism<br />

without spatial illusion, unless you count<br />

the shadows as illusion. And the crates were<br />

also boxes, appropriate places to show off<br />

her bits and pieces. Ahead lay the great wall<br />

pieces.<br />

As for these collages they are another<br />

repository for her essential bits and pieces.<br />

The pieces <strong>Nevelson</strong> liked to show off,<br />

turn into something else, build with, play<br />

with, create with. Like the bits and pieces<br />

she had begun collecting as a girl of six in<br />

Rockland, Maine.<br />

<strong>Anthony</strong> <strong>Haden</strong>-<strong>Guest</strong><br />

Page 22<br />

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> at age twenty, c. 1919;<br />

Photographer unknown; Farnsworth Art Museum<br />

<strong>Nevelson</strong> Archive.<br />

Above<br />

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> standing in profile, ca. 1974;<br />

Arnie Zane, photographer; Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> papers,<br />

Archives of American Art.<br />

Page 24<br />

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong>, captain of the Rockland High<br />

School girls basketball team, Rockland, Maine,<br />

1916; Photographer unknown; Farnsworth Art<br />

Museum <strong>Nevelson</strong> Archive.<br />

Page 25<br />

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> in the kitchen of her East 30th<br />

Street home, c. 1954, with column form First<br />

Personage, completed in 1956; Photograph by<br />

Richard Goodbody; Farnsworth Art Museum<br />

<strong>Nevelson</strong> Archive.<br />

23

Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong><br />

The way I think is collage<br />

Publication © Galerie Gmuryznska, 2012<br />

Credits<br />

Concept: Krystyna Gmurzynska, Mathias Rastorfer<br />

Coordination: Mitchell Anderson, Jeannette Weiss<br />

Support: Guadalupe Alonso, Alessandra Consonni<br />

Texts:<br />

Robert Indiana<br />

Bill Katz<br />

<strong>Anthony</strong> <strong>Haden</strong>-<strong>Guest</strong><br />

Printed by: Grafiche Step, Parma<br />

Photographs:<br />

© Arnold Newman/Getty Images<br />

© Mike Zwerling, Courtesy of the Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> papers, ca. 1903-1979,<br />

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution<br />

© Steve Balkin, Courtesy of the Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> papers, ca. 1903-1979,<br />

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution<br />

© Tom Jones, Farnsworth Art Museum <strong>Nevelson</strong> Archive<br />

© Diana MacKown, Courtesy of the Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> papers, ca. 1903-1979,<br />

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution<br />

© Arnold Newman/Getty Images<br />

© Mort Kaye Studios, Inc., Courtesy of the Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> papers, ca. 1903-1979,<br />

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.<br />

© Farnsworth Art Museum <strong>Nevelson</strong> Archive<br />

© Arnie Zane, Courtesy of the Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> papers, ca. 1903-1979,<br />

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution<br />

© Richard Goodbody, Farnsworth Art Museum <strong>Nevelson</strong> Archive<br />

© John Pedin/NY daily News Archive via Getty Images<br />

© Ara Guler, Courtesy of the Louise <strong>Nevelson</strong> papers, ca. 1903-1979,<br />

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution<br />

© Robin Platzer/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images<br />

© Diana Walker/ Time Life Pictures/Getty Images<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted<br />

or reproduced in anyform or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means,<br />

now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording,<br />

or in any information retrieval system, without prior written permission from the copyright holders.<br />

ISBN<br />

3-905792-02-8<br />

978-3-905792-02-7