Anthony Haden-Guest – Wifredo Lam / Jean-Michel Basquiat

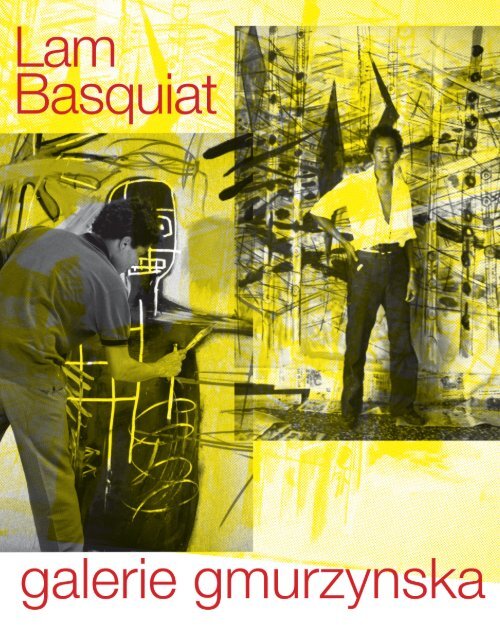

Excerpt from “Lam/Basquiat”, a catalog published by Galerie Gmurzynska on the occasion of a special presentation at Art Basel 2015, prepared in collaboration with Annina Nosei.

Excerpt from “Lam/Basquiat”, a catalog published by Galerie Gmurzynska on the occasion of a special presentation at Art Basel 2015, prepared in collaboration with Annina Nosei.

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Wifredo <strong>Lam</strong> / <strong>Jean</strong>-<strong>Michel</strong> <strong>Basquiat</strong><br />

by <strong>Anthony</strong> <strong>Haden</strong>-<strong>Guest</strong><br />

It was while <strong>Jean</strong>-<strong>Michel</strong> <strong>Basquiat</strong><br />

was working in Annina Nosei’s downstairs<br />

space that he became familiar with the<br />

work of Wifredo <strong>Lam</strong>. It seems that<br />

<strong>Basquiat</strong> was in the process of looking over<br />

the work of other artists that caught his<br />

attention - Nosei had suggested he check<br />

out the Cobra group, for instance - and he<br />

had been strongly drawn to <strong>Lam</strong>. Dieter<br />

Buckhart, the Viennese curator who put<br />

together the remarkable show of <strong>Basquiat</strong><br />

notebooks for the Brooklyn Museum,<br />

simply says that <strong>Lam</strong> was “on <strong>Basquiat</strong>’s<br />

ladder.”<br />

Not hard to see why. Not only did<br />

<strong>Lam</strong> have preternatural skills in picturemaking<br />

but <strong>Basquiat</strong> and <strong>Lam</strong> shared<br />

biographical background of a nature well<br />

fitted to feed into the making of those<br />

pictures. Both were of mixed race. And<br />

similarly mixed race. Wifredo was the<br />

eighth child of <strong>Lam</strong>-Yam, an emigrant to<br />

the Americas from Canton, and his mother,<br />

Ana Serafina Catilla, was of mixed African<br />

and Spanish stock. <strong>Basquiat</strong>’s father,<br />

Gerard, was a Haitian of African descent,<br />

his mother Matilde was Puerto Rican. So<br />

both were a melange, yes, but both looked<br />

African. Which means being identified as<br />

African in most of the world. You don’t<br />

believe me? Feel free to check with Barack<br />

Obama or Tiger Woods on this.<br />

<strong>Lam</strong> was born in Sagua la Grande,<br />

a township on the coast of Cuba, on<br />

December 8, 1902. He would often say<br />

that his first intuition of the marvelous was<br />

the shadow of a bat fluttering through<br />

his bedroom when he was five. The family<br />

moved to Havana when he was in his early<br />

teens and he was sent none too willingly<br />

to study law. He went to an art school<br />

instead, disliked the Beaux Arts training,<br />

but got a grant to study in Europe and<br />

left for Madrid when he was 21, planning<br />

to soon move on to Paris. Actually he<br />

spent fourteen years in Spain, joining an<br />

avant-garde group where he made art<br />

variously inflected with Cubism, Fauvism<br />

and Surrealism. But in 1931 his first wife and<br />

their son died of TB, darkening his world.<br />

<strong>Lam</strong> fought for the Republicans in<br />

the Spanish Civil War, took part in the<br />

defense of Madrid. He then finally made his<br />

way to Paris, arriving in the beating heart<br />

of the avant-garde on May 1, 1938, armed<br />

with a letter of introduction to Picasso,<br />

given to him by the Catalan sculptor<br />

Manolo Hugue. Havana, <strong>Lam</strong>’s former<br />

hometown, was not, of course, “primitive”<br />

but the capital of a former colonial culture<br />

and <strong>Lam</strong>, whose family had wanted him to<br />

be a lawyer, was scarcely tribal, but this<br />

did not prevent his perceived African-ness<br />

from being a plus with the Parisian avantgarde,<br />

who had long been channeling<br />

the energy of tribal art. Indeed their<br />

use of it had sometimes been attacked<br />

as exploitative, an avant-garde form of<br />

colonialism, but it was actually a matter<br />

14

of using that raw, brimming energy<br />

to undermine the genteel salons. As<br />

when Josephine Baker, the dancer who<br />

electrified the Paris of the 20s in La<br />

Revue Negre, had observed, “For too long<br />

people have hidden their behinds. I see<br />

no reason to be ashamed of them.”<br />

Picasso told Andre Malraux in 1937<br />

that his discovery of the energy in tribal<br />

art and artifacts had begun when he<br />

had been overwhelmed on a visit to the<br />

Ethnographic Museum in the Palais de<br />

Trocadero. “The masks weren’t just like<br />

any other pieces of sculpture,” he said.<br />

“Not at all. They were magic things. Les<br />

Demoiselles d’Avignon must have come<br />

to me that very day.” He had made that<br />

painting - arguably the first “modern”<br />

artwork - in 1907. This is a Picassoid<br />

reading, of course, and it has been<br />

claimed that it was Derain who brought<br />

the work to his attention. But that<br />

Picasso got the most oomph! out of the<br />

encounter is not open to question.<br />

Picasso and Wifredo <strong>Lam</strong> did duly<br />

meet. And Picasso took to the Cuban right<br />

away. “Even if you hadn’t brought me a<br />

letter from Manolo, I would have noticed<br />

you in the street,” Picasso told <strong>Lam</strong> later.<br />

“And I would have thought: I absolutely<br />

must make a friend of this man.” He quickly<br />

saw to it that <strong>Lam</strong> met the creme de la<br />

creme of the avant garde, introducing him<br />

to Max Ernst, Andre Breton, Tristan Tzara,<br />

Fernand Leger, Henri Matisse, George Braque<br />

and <strong>Michel</strong> Leiris, who was a Surrealist and<br />

the director of the Black Africa department<br />

in the Trocadero, and who would in due<br />

course write a book about <strong>Lam</strong>.<br />

The tutelary Picasso/<strong>Lam</strong><br />

relationship was discussed at the<br />

time and it makes for an interesting<br />

comparison with the young/old, black/<br />

white relationship between <strong>Jean</strong>-<br />

<strong>Michel</strong> <strong>Basquiat</strong> and Andy Warhol. One<br />

significant difference is that Picasso was<br />

no way perceived as being in a creative<br />

slump - indeed was accelerating from<br />

one prime into another - whereas Warhol<br />

could be seen as needing <strong>Basquiat</strong> rather<br />

more than vice versa. A more serious<br />

distinction, though, was that <strong>Basquiat</strong>,<br />

young though he was, was already a<br />

developed artist when he began to work<br />

with Andy Warhol, whereas Picasso<br />

saw promise in the work of the still<br />

evolving <strong>Lam</strong>, who was soon perceived<br />

as his protégé. Indeed the part Picasso<br />

played in his flowering was huge, and<br />

included getting him a dealer, Pierre<br />

Loeb, who put it on the record that he<br />

visited <strong>Lam</strong>’s studio with Picasso.<br />

Loeb said, while looking at the work,<br />

“He is influenced by blacks.”<br />

Picasso said, “He has the right, he<br />

IS black.”<br />

15

<strong>Lam</strong> had his first solo show in Paris<br />

with the Loeb gallery in the summer of<br />

1939. Those who attended his opening<br />

included Le Corbusier and Marc Chagall.<br />

And that same year Picasso and <strong>Lam</strong><br />

showed together at the Perls Gallery in<br />

New York, as Warhol and <strong>Basquiat</strong> would<br />

almost half a century later.<br />

I should note that many of the<br />

details above come from a 2003 essay<br />

by <strong>Michel</strong>e Greet, entitled Inventing<br />

Wifredo <strong>Lam</strong>: The Parisian Avant-<br />

Garde’s Primitivist Fixation. In this<br />

Greet observes that “during his time in<br />

Paris, <strong>Lam</strong> did not employ Africanizing<br />

forms as a reflection of his Afro-Cuban<br />

heritage, but rather he engaged these<br />

forms as a means of emulating the<br />

modernity of the Parisian avant-garde,<br />

and in so doing, definitively breaking<br />

with his academic training. <strong>Lam</strong> was<br />

attracted to Picasso’s incorporation of<br />

primitive forms to invent visually new<br />

and challenging images … <strong>Lam</strong> began<br />

to explore the possibility of imbuing<br />

these formal constructions with meaning<br />

specific to his identity as an Afro-Cuban.”<br />

So. It was 1940 and <strong>Lam</strong> went<br />

down to Marseilles in Vichy France to<br />

dodge the Nazis. There he became a<br />

habitué of the Villa Air-Bel, HQ for<br />

the “Defense of Intellectuals Menaced<br />

by Nazism,” which was run by a<br />

gentlemanly American, Varian Fry,<br />

who described <strong>Lam</strong> as “the tragicmasked<br />

Cuban Negro who was one of<br />

the very few pupils Picasso ever took.”<br />

Amongst the Menaced Intellectuals<br />

were a number of Surrealists, including<br />

Andre Masson, Max Ernst, Victor<br />

Brauner and Andre Breton, who<br />

picked <strong>Lam</strong> to illustrate his poem<br />

Fata Morgana. In retrospect it was a<br />

last gasp of the primacy of the Paris<br />

avant-garde. And the following year<br />

Wifredo <strong>Lam</strong> was back in Cuba.<br />

* * *<br />

Yes, <strong>Lam</strong> was back, with his<br />

mother and his three sisters, but<br />

Havana was greatly changed. Under<br />

the Batista regime, the capital was<br />

Americanized, a tourist playground,<br />

utterly disregarding the hard lives of the<br />

peasantry in the countryside. “For me,<br />

seeing Europe had been everything,”<br />

he wrote. <strong>Lam</strong>’s humanitarian nature,<br />

the side of him that had labored making<br />

anti-Franco posters was reawakened.<br />

“What I saw on my return looked like<br />

Hell,” he wrote. “All the drama of the<br />

colonialism of my youth resurfaced in<br />

me.”<br />

Nor that only. His sister Eloisa<br />

well acquainted with the venerable<br />

rituals of Santeria. “When I came<br />

back to Cuba, I was taken back by<br />

its nature, by the traditions of the<br />

Blacks, and by the transculturation of<br />

its African religions. And so I began<br />

to orientate my paintings towards the<br />

African.”<br />

Eloisa arranged for her brother<br />

and a friend, Alejo Carpentier, one of<br />

the writers who had formulated the<br />

key Latin-American concept, Magic<br />

Realism, to participate in the rites. It<br />

was as if the pictorial language which<br />

had helped Picasso and the Cubists<br />

construct Modernism was now <strong>Lam</strong>’s<br />

to use for real.<br />

16

Wifredo <strong>Lam</strong> with Pablo Picasso, Cannes, 1954<br />

It was at the suggestion of Andre<br />

Breton that he was offered a New York<br />

show by Pierre Matisse. The younger son<br />

of the artist had moved to New York and<br />

opened a gallery twenty years before.<br />

He was now operating out of the Fuller<br />

Building on East 57th, where he showed<br />

Giacometti, Derain, Dubuffet, Balthus<br />

and Le Corbusier. Wifredo <strong>Lam</strong> might<br />

as well have been back in Paris. Back<br />

in Cuba <strong>Lam</strong> worked as never before.<br />

MoMA bought his 1943 canvas, La Jungla.<br />

They hung it alongside Les Demoiselles<br />

d’Avignon.<br />

Wifredo <strong>Lam</strong> died in September<br />

1982. That March <strong>Jean</strong>-<strong>Michel</strong><br />

<strong>Basquiat</strong> had his first one-man<br />

show at the Annina Nosei Gallery.<br />

It did extremely well. A review by<br />

Jeffrey Deitch read “<strong>Basquiat</strong>’s great<br />

strength is his ability to merge his<br />

absorption of imagery from the<br />

streets, the newspapers, and TV<br />

with the spiritualism of his Haitian<br />

heritage, injecting both into a<br />

marvelously intuitive understanding<br />

of the language of modern painting.”<br />

Good call.<br />

17

Publication © Galerie Gmurzynska 2015<br />

For the works by <strong>Jean</strong>-<strong>Michel</strong> <strong>Basquiat</strong> and Wifredo <strong>Lam</strong>:<br />

© 2015, ProLitteris, Zurich<br />

Documentary Images of Wifredo <strong>Lam</strong> SDO Wifredo <strong>Lam</strong><br />

Editors:<br />

Krystyna Gmurzynska<br />

Mathias Rastorfer<br />

Mitchell Anderson<br />

Coordination:<br />

<strong>Jean</strong>nette Weiss, Daniel Horn<br />

Support:<br />

Alessandra Consonni<br />

Cover design:<br />

Louisa Gagliardi<br />

Design by OTRO<br />

James Orlando<br />

Brady Gunnell<br />

Texts:<br />

Jonathan Fineberg<br />

<strong>Anthony</strong> <strong>Haden</strong>-<strong>Guest</strong><br />

Kobena Mercer<br />

Annina Nosei<br />

PRINTED BY<br />

Grafiche Step, Parma<br />

ISBN<br />

3-905792-28-1<br />

978-3-905792-28-7