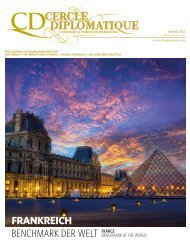

CERCLE DIPLOMATIQUE - issue 04/2020

CD is an independent and impartial magazine and is the medium of communication between foreign representatives of international and UN-organisations based in Vienna and the Austrian political classes, business, culture and tourism. CD features up-to-date information about and for the diplomatic corps, international organisations, society, politics, business, tourism, fashion and culture. Furthermore CD introduces the new ambassadors in Austria and informs about designations, awards and top-events. Interviews with leading personalities, country reports from all over the world and the presentation of Austria as a host country complement the wide range oft he magazine.

CD is an independent and impartial magazine and is the medium of communication between foreign representatives of international and UN-organisations based in Vienna and the Austrian political classes, business, culture and tourism. CD features up-to-date information about and for the diplomatic corps, international organisations, society, politics, business, tourism, fashion and culture. Furthermore CD introduces the new ambassadors in Austria and informs about designations, awards and top-events. Interviews with leading personalities, country reports from all over the world and the presentation of Austria as a host country complement the wide range oft he magazine.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

LE MONDE ESSAY

Lebanon – a microcosm of the

rest of the world

Karin Kneissl

studied law and Arabic at

the University of Vienna.

She later served as an

Austrian diplomat in the

office of the Legal Advisor,

Cabinet of the minister,

Middle East Desk and was

posted among others in

Paris and Madrid. Later on,

she worked as an

independent correspondent

on energy affairs, analyst

and university lecturer

(Vienna, Beirut). She served

as Austrian Foreign Minister

from December 2017 – June

2019. Thereafter, she

returned to her independent

work. She has written

various books, numerous

papers and articles on the

topics of geopolitics, energy

and international relations.

kkneissl.com

Endless wars, terrorism, social unrest, immense corruption and a tremendous

explosion – is a list of what it means to live in Lebanon. The Lebanese

are professional survivors and most of what I have learnt about life, they

have taught me – also to understand what might be happening next in our

own societies west of Beirut.

The name Lebanon is much older than the Lebanese

republic. We can read it in King

Solomon’s Song of Songs and so many other

texts, like the Tell el Amarna tablets. This is a correspondence

on tiny tiles, excavated by archaeologists

in Egypt, and a fascinating collection of classic complaints

by diplomats about their posts. I enjoyed reading

the translations in the Cairo Museum of Antiquities

many years ago, for they prove that really

little changes in human civilisation, notably in the

history of diplomacy. Most of the pieces stem from

the time of Pharaoh Amenophis III, whose court was

in close contact with its vassals in Byblos in what is

currently Lebanon. The importance of cedar wood

for the fabrication of coffins has put Mount Lebanon

on the map of geopolitics ever since.

Going global long ago

Millenia ago, Phoenician merchants spread from

the Mediterranean to the African coasts, maybe even

farther. They created an “after sale service” for their

trading points, circulated new ideas and innovative

techniques, including the alphabet, which they had

encountered in Ugarit. They contributed to globalisation

as it existed several thousands of years ago. To

emigrate has since been part of the Lebanese culture,

though they always keep in touch with their country

of origin. In addition to approximately five million Lebanese

in Lebanon, 12 million others dispose of a Lebanese

passport but live elsewhere. Their remittances

from the Americas, the Gulf etc. keep the country

running. Migration has always been a feature of Lebanon,

some left out of curiosity for foreign lands, others

left out of despair.

The term “Lebanisation” is equal to “Balkanisation”,

and they are often interchanged in political sciences.

Both refer to the implosion of a state, the dismantling

of institutions and the rise of tiny units to the

detriment of a central structure. Once the state’s monopoly

of force is weakened, militias enter the scene.

When Lebanon drowned in the proxy war of the

1970s, analysts referred to the “Balkanisation of Lebanon”.

And in the 1990s, the break-up of Yugoslavia

was called by many historians: the Lebanisation of Yugoslavia.

The Soviet Union was balkanised/lebanised,

Spain and the United Kingdom might be on the brink

of a similar dissolution. However, Lebanon is still there

on the map, both as a state and a society. This fact is

quite admirable, for too many commentators have announced

the end of Lebanon, again and again.

Corruption is the name of the game

When I had the honour to speak at the General Assembly

of the United Nations in September 2018, I

took the opportunity to pay tribute to Lebanon’s amazing

capacity for survival. I decided to start my speech

in Arabic, one of the six official UN-languages. In my

remarks I referred to the Lebanese determination to

continue living with dignity and elegance. While

many of my Austrian compatriots have lost the sense

of putting on nice clothes, polishing shoes and many

other tiny but important features of everyday life, the

Lebanese still cherish those habits no matter what.

You may call it superficial, I consider it a sort of resistance

against ugliness.

The Lebanese have been surviving wars, bombings

by their neighbours and a constant influx of refugees.

And they have somehow managed to live through it all.

But what has finally broken the backbone of the Lebanese

society is the omnipresent corruption that plagues

the society. It starts with buying and selling university

diplomas in the commercialised private education system

and includes moves to obtain medical aid and find

work. Everything is done via “wasta” which is the Arabic

word for “connection”, i.e. corruption. The entire

political structure which is based on a confessional

partition of power represents one big corrupt system,

providing the people with totally inadequate public

services. Add to this the expansive and dubious world

of non-governmental organisations which have become

a business branch of their own. This combination

has been lethal to the Lebanese society.

The result is a high degree of frustration by Lebanese

of all age groups. In October 2019, hundreds of

thousands of them decided to descend into the streets

and ask for an end to the mess. The movement was

PHOTOS: FELICITAS MATERN, ADOBE STOCK

called a revolution, but a year later nothing has changed.

The same faces still hold the same posts. A terrible

explosion in the port of Beirut on August 4 this year,

hit the capital and destroyed thousands of apartments.

Here also, corruption is most probably the culprit as

several police reports had been warning the port authorities

that chemicals stocked there for years could

cause an inferno. Nobody acted.

Orientation and the Orient

In Latin the saying goes: ex oriente lux – Orientation

comes from Orient. Ever since the antiquity, we

always look to the East for guidance. In the 1980s, not

only did Lebanon go through wars, but also through

horrible terrorist attacks. In the 1990s it went through

the destruction of its cities and nature by wild and corrupt

construction. Confessionalism broke and fragmented

the society even more than the war. Being

Lebanese became a statement of one’s ethnic confessional

identity. As a result, state structures weakened;

private money increasingly replaced public funds.

Ever since my first journey in 1989 to this “petit pays

qui fait tant de bruit” (this small country that makes so

much noise) as Metternich said in 1830 on the occasion

of the first humanitarian intervention of history, I

have been fascinated and appalled at the same time.

Lebanon is a laboratory of political and social developments.

What happens there, repeats itself in

many ways in other parts of the world. Terrorism, ethnicism,

religious extremism, breakdown of state institutions,

corruption: you name it, you have it. In past

years, when speaking on the Middle East, I regularly

pointed out the return of the social question. The Arab

revolts of 2011 were more about unemployment, corruption,

lack of housing, etc. The slogans were dignity,

justice and freedom.

Similar outbreaks of frustration are to be expected

in the near future in many cities around the world.

The notion of the “angry citizen” became famous in

2010 with the pamphlet of the former French Resistance

member and diplomat Stéphane Hessel, entitled

“Indignez-vous!” (“Time for Outrage!”). What might

be different from previous demonstrations such as the

“Yellow Vests” in France and the “Occupy Wall Street”

movement is that these demonstrations will be led by

people who are not simply angry, but desperate. This is

what happened in Lebanon last year, and it can happen

elsewhere soon. The question is whether we will

be able to survive in dignity and elegance, as the Lebanese

do.

View of Lebanon’s capital

Beirut, before the explosion

on August 4, this year.

46 Cercle Diplomatique 4/2020

Cercle Diplomatique 4/2020

47