LSB September 2021 LR

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

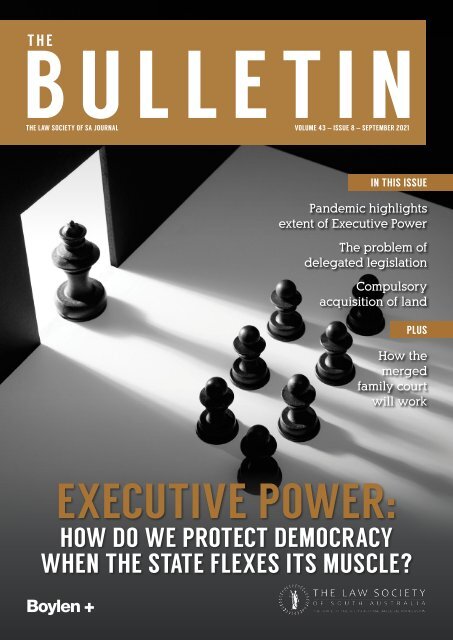

THE<br />

BULLETIN<br />

THE LAW SOCIETY OF SA JOURNAL<br />

VOLUME 43 – ISSUE 8 – SEPTEMBER <strong>2021</strong><br />

IN THIS ISSUE<br />

Pandemic highlights<br />

extent of Executive Power<br />

The problem of<br />

delegated legislation<br />

Compulsory<br />

acquisition of land<br />

PLUS<br />

How the<br />

merged<br />

family court<br />

will work<br />

EXECUTIVE POWER:<br />

HOW DO WE PROTECT DEMOCRACY<br />

WHEN THE STATE FLEXES ITS MUSCLE?

Successful law firms<br />

are agile<br />

Whether you’re at home or back in the office,<br />

LEAP lets you work with flexibility. Transition to<br />

LEAP and take advantage of integrated matter<br />

management, document automation and legal<br />

accounting in one platform.<br />

leap.com.au/agile-law-firms

This issue of The Law Society of South Australia: Bulletin is<br />

cited as (2020) 43 (8) <strong>LSB</strong>(SA). ISSN 1038-6777<br />

CONTENTS<br />

EXECUTIVE POWER FEATURES & NEWS REGULAR COLUMNS<br />

6 The march of executive authority<br />

highlights fragility of democracy<br />

By Morry Bailes AM<br />

10 The problem of delegated legislation<br />

in South Australia<br />

By Assoc Prof Lorne Neudorf<br />

12 Covid-Safe check-in: use beyond<br />

contact tracing? – By Raffaele Piccolo<br />

16 The exercise of emergency powers<br />

by the executive in COVID-19<br />

times: What recent cases say about<br />

constitutional protection of our<br />

freedoms – By Sue Milne<br />

24 Compulsory Acquisition of Land:<br />

Navigating the intersection between<br />

executive powers and individual<br />

property rights – By Don Mackintosh<br />

22 Harassment in the legal industry:<br />

Cultural change requires a movement,<br />

not a mandate – By Alexia Bailey &<br />

Marissa Mackie<br />

28 Introduction of the Federal Circuit<br />

and Family Court of Australia<br />

By The Hon Chief Justice Will Alstergren<br />

34 Event report: Country Conference on<br />

Kangaroo Island – By Alan Oxenham<br />

36 The venerable common law forfeiture<br />

rule and suggestions for reform<br />

By Dr David Plater & Dr Sylvia Villios<br />

42 Steering statutory unconscionability<br />

out of a jam at last: Stubbings v Jams<br />

2 Pty Ltd – By Dr Gabrielle Golding &<br />

Dr Mark Giancaspro<br />

4 President’s Message<br />

5 From the Editor<br />

9 From the Conduct Commissioner:<br />

Poaching clients from your former<br />

firm – By Greg May<br />

19 Wellbeing & Resilience: R U OK? U R<br />

are not alone – By Zoe Lewis<br />

20 Young Lawyers: Dancing privileges<br />

embraced at pre-lockdown Young<br />

Professionals’ Gala<br />

32 Tax Files: Loan accounts: trouble?<br />

By Stephen Heath<br />

33 Members on the Move<br />

39 Bookshelf<br />

40 Risk Watch: Time to tame your inbox<br />

By Mercedes Eyers-White<br />

45 Family Law Case Notes<br />

By Craig Nichol & Keleigh Robinson<br />

46 Gazing in the Gazette<br />

Executive Members<br />

President:<br />

R Sandford<br />

President-Elect: J Stewart-Rattray<br />

Vice President: A Lazarevich<br />

Vice President: V Gilliland<br />

Treasurer:<br />

F Bell<br />

Immediate Past<br />

President:<br />

T White<br />

Council Member: M Mackie<br />

Council Member: M Tilmouth<br />

Metropolitan Council Members<br />

T Dibden<br />

M Tilmouth<br />

A Lazarevich M Mackie<br />

M Boyle<br />

E Shaw<br />

J Marsh<br />

C Charles<br />

R Piccolo<br />

M Jones<br />

Country Members<br />

S Minney<br />

(Northern and Western Region)<br />

P Ryan<br />

(Central Region)<br />

J Kyrimis<br />

(Southern Region)<br />

Junior Members<br />

vacant<br />

Ex Officio Members<br />

The Hon V Chapman, Prof V Waye,<br />

Prof T Leiman<br />

Assoc Prof Peter Burdon<br />

KEY LAW SOCIETY CONTACTS<br />

Chief Executive<br />

Stephen Hodder<br />

stephen.hodder@lawsocietysa.asn.au<br />

Executive Officer<br />

Rosemary Pridmore<br />

rosemary.pridmore@lawsocietysa.asn.au<br />

Chief Operations Officer<br />

Dale Weetman<br />

dale.weetman@lawsocietysa.asn.au<br />

Member Services Manager<br />

Michelle King<br />

michelle.king@lawsocietysa.asn.au<br />

Director (Ethics and Practice)<br />

Rosalind Burke<br />

rosalind.burke@lawsocietysa.asn.au<br />

Director (Law Claims)<br />

Kiley Rogers<br />

krogers@lawguard.com.au<br />

Manager (LAF)<br />

Annie MacRae<br />

annie.macrae@lawsocietysa.asn.au<br />

Programme Manager (CPD)<br />

Natalie Mackay<br />

Natalie.Mackay@lawsocietysa.asn.au<br />

Programme Manager (GDLP)<br />

Desiree Holland<br />

Desiree.Holland@lawsocietysa.asn.au<br />

THE BULLETIN<br />

Editor<br />

Michael Esposito<br />

bulletin@lawsocietysa.asn.au<br />

Editorial Committee<br />

A Bradshaw P Wilkinson<br />

S Errington D Sheldon<br />

J Arena D Weekley<br />

B Armstrong D Misell<br />

M Ford<br />

The Law Society Bulletin is published<br />

monthly (except January) by:<br />

The Law Society of South Australia,<br />

Level 10-11, 178 North Tce, Adelaide<br />

Ph: (08) 8229 0200<br />

Fax: (08) 8231 1929<br />

Email: bulletin@lawsocietysa.asn.au<br />

All contributions letters and enquiries<br />

should be directed to<br />

The Editor, The Law Society Bulletin,<br />

GPO Box 2066,<br />

Adelaide 5001.<br />

Views expressed in the Bulletin<br />

advertising material included are<br />

not necessarily endorsed by The<br />

Law Society of South Australia.<br />

No responsibility is accepted by the<br />

Society, Editor, Publisher or Printer<br />

for accuracy of information or errors<br />

or omissions.<br />

PUBLISHER/ADVERTISER<br />

Boylen<br />

GPO Box 1128 Adelaide 5001<br />

Ph: (08) 8233 9433<br />

Email: admin@boylen.com.au<br />

Studio Manager: Madelaine Raschella<br />

Elliott<br />

Layout: Henry Rivera<br />

Advertising<br />

Email: sales@boylen.com.au

FROM THE EDITOR<br />

Buoyant mood as profession<br />

celebrates peers<br />

MICHAEL ESPOSITO, EDITOR<br />

In a Herculean feat of logistics and<br />

planning, the Law Society held its Legal<br />

Professional Dinner on Friday 27 August,<br />

hosting a buoyant congregation of 300<br />

guests.<br />

While immense credit must go to the<br />

organising staff of the Society and SkyCity<br />

for putting on such a successful event,<br />

especially after the disappointment of<br />

last-year’s lockdown-induced cancellation,<br />

particular gratitude must go to practitioners<br />

who attended the event in such high spirts.<br />

Despite a number of restrictions being<br />

imposed on guests, including compulsory<br />

mask wearing, a strict no dancing policy,<br />

and a ban on that most time-honoured<br />

of social custom – vertical consumption<br />

– it was so heart-warming to see such an<br />

enthusiastic response to the event.<br />

It was also a privilege to honour the<br />

nominees and award winners on the<br />

night, and particular to hear about their<br />

incredible achievements.<br />

The Women’s Domestic Violence<br />

Court Assistance Service was the<br />

highly deserving winner of the Justice<br />

Award. The staff who work at the<br />

service help women who have been<br />

exposed to domestic violence navigate<br />

the justice system. They provide advice<br />

about intervention orders and tenancy<br />

disputes, and have guided thousands of<br />

clients through the process, including all<br />

throughout the pandemic. The importance<br />

of this cannot be overestimated. One<br />

particularly moving note from a client<br />

read: “Thank you for giving us our freedom and<br />

safety back. My kids are now growing up in a<br />

home free of DV abuse because of your help.”<br />

The four Young Lawyer of the Year<br />

nominees showed that the future of the<br />

law is indeed in good hands. In a hotly<br />

contested field, Antonella Rodriguez was<br />

named Young Lawyer of the Year. The<br />

family lawyer excelled in her first role as<br />

Associate to Justice Berman in the Family<br />

Court of Australia and has continued to<br />

impress at current firm Tolis & Co. As an<br />

associate, Antonella was heavily involved in<br />

the Judicial Council on Cultural Diversity’s<br />

efforts to improve services to culturally<br />

diverse participants in the justice system.<br />

Antonella has also been volunteering<br />

with the Red Cross Emergency Services,<br />

assisting people to access shelter,<br />

resources, and emergency funds and<br />

reuniting families following last year’s<br />

bushfires.<br />

She volunteers in numerous other<br />

environmental organisations, in yet<br />

another example of practitioners making<br />

time to give back to the community.<br />

The Mary Kitson Award winner,<br />

for outstanding contribution to the<br />

advancement of women in the profession,<br />

was presented to the trailblazing Justice<br />

Trish Kelly.<br />

Justice Trish Kelly’s exceptional legal<br />

career alone is a source of inspiration<br />

for women in the profession. In her<br />

roles as prosecutor at both State and<br />

Federal level, a senior legal officer at the<br />

Equal Opportunity Commission, and of<br />

course judicial officer culminating in her<br />

appointment as the inaugural President<br />

of the Court of Appeal, Justice Kelly has<br />

been a purveyor of the law par excellence,<br />

and her contribution to protecting the<br />

rights of victims of crime has been<br />

particularly noteworthy. In addition,<br />

Justice Kelly has been a Member of the<br />

Intellectually Disabled Services Council of<br />

South Australia and a member of the Rape<br />

Crisis Centre Board.<br />

It’s pleasing to see gender equity<br />

become an important issue for the<br />

judiciary, and Justice Sam Doyle’s<br />

considered article “The path to gender<br />

equality requires removing cultural &<br />

structural barriers in the profession”<br />

reflects the heightened awareness and<br />

commitment to the cause. His article won<br />

the “Bulletin Article of the Year - Special<br />

Interest Category” on Friday Night. The<br />

Attorney General, The Hon Vicki Chapman MP,<br />

flanked by Danielle Stopp (left) and Bianca Paterson<br />

of the Women's Domestic Violence Court Assistance<br />

Service, which won the Justice Award.<br />

Young Lawyer of the Year winner Antonella Rodriguez<br />

(second from left) with (from left), Young Lawyers<br />

Committee Co-Chair Patrick Kerin, Law Society<br />

President Bec Sandford, and Young Lawyers<br />

Committee Co-Chair Bianca Geppa.<br />

Bulletin Article of the Year, among a<br />

field of exceptional articles, went to<br />

Dr Philip Ritson for his article “Supreme<br />

Court decision highlights pitfalls of raising<br />

money for charitable purposes”.<br />

There are so many members of the<br />

profession who may never win awards but<br />

are equally deserving of commendation,<br />

despite never seeking praise for their<br />

outstanding contributions to the<br />

community. Let me take this opportunity to<br />

thank all of those who serve the profession<br />

and broader society in their own way.<br />

A more detailed wrap-up of the Legal<br />

Profession Dinner will be published in the<br />

October edition of the Bulletin. B<br />

4<br />

THE BULLETIN <strong>September</strong> <strong>2021</strong>

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE<br />

Emergency powers must not<br />

lead to long-term immunity<br />

from checks & balances<br />

REBECCA SANDFORD, PRESIDENT<br />

Terms like ‘rule of law’ and ‘separation<br />

of powers’ are often thrown around,<br />

but some of us may not have had cause to<br />

think about those concepts in much depth<br />

in our day to day lives after finishing law<br />

school - at least, not until last year. The<br />

pandemic, and the state of emergency<br />

it ushered in, resulted in huge changes<br />

to the way the law affects our lives, and<br />

to executive power being exercised in<br />

previously unanticipated ways.<br />

By way of brief reminder for those<br />

of us whose attendance at legal theory<br />

tutorials may feel like a distant memory,<br />

the separation of powers allows us to<br />

have confidence that in our system of<br />

responsible government, each of the<br />

Parliament, Executive and Judiciary will<br />

balance the power able to be exercised<br />

by each other ‘arm’ of that triad. Our<br />

Members of Parliament are elected to<br />

represent us and make decisions on our<br />

behalf, and if they don’t do that in a way<br />

which is appropriate or responsible, the<br />

consequences may include court action to<br />

strike down invalid laws, or the voting in<br />

of a different representative at the next<br />

possible opportunity.<br />

Ordinarily, decisions which generally<br />

affect the lives and liberties of citizens vest<br />

in the Parliament or in the Government.<br />

Those bodies make use of consultative<br />

processes which can enable adverse<br />

consequences to be identified and<br />

addressed, prior to the implementation<br />

of any new legal regime. The Law Society<br />

plays a role in that process, including<br />

through the making of submissions<br />

and public comment on legal matters.<br />

The decisions made by Government,<br />

and implemented through laws made by<br />

Parliament, are the subject of scrutiny in<br />

a number of respects, including by way of<br />

judicial review.<br />

In emergency situations, it makes<br />

sense to consolidate more of the decision<br />

making power in a central or singular<br />

location, and to remove for a short time<br />

some of the checks and balances that<br />

would otherwise exist to prevent improper<br />

use of that power, recognizing that an<br />

extraordinary situation is at play and<br />

that the exercise of those accountability<br />

processes may prevent the ability of<br />

the Government to deliver support or<br />

assistance, or regulate behaviour, as needed<br />

to keep things functioning despite unusual<br />

circumstances. However, that ordinarily<br />

occurs only for a limited time, and a return<br />

to ‘normal’ processes occurs as promptly<br />

as possible. The pandemic has seen a<br />

number of unprecedented approaches to<br />

the use of executive power, and potentially<br />

demonstrated the need for a refreshed<br />

look at how executive power is managed in<br />

an emergency situation.<br />

In SA, the Parliament was initially<br />

responsible for the creation of the<br />

Emergency Management Act, under<br />

which a state of emergency can be<br />

declared. If that occurs, responsibility<br />

for managing that emergency falls to<br />

the State Coordinator, a position held<br />

by the Commissioner of Police - an<br />

unelected position, but perhaps the one<br />

best suited to coordinate a rapid response<br />

to an emergency. It is via the powers<br />

provided for by that Act and in relation<br />

to that position that the Commissioner<br />

of Police, in the last 18 months, has<br />

issued directions which have required us<br />

to isolate or quarantine, get covid-tested,<br />

check in with QR codes wherever we<br />

go, and restrict attendance at businesses,<br />

weddings, funerals and other gatherings.<br />

It has become apparent, as a result of<br />

the state of emergency declared in SA<br />

last March (and refreshed on a monthly<br />

basis since then) that the current regime<br />

when used in practice actually vests a<br />

significant amount of executive power in<br />

the State Coordinator. I certainly don’t<br />

envy our Commissioner of Police that<br />

responsibility, and whilst the consultative<br />

and collaborative approach taken in<br />

the exercise of that power to date is<br />

commendable, we must still be mindful<br />

that consultation is not required, and it is<br />

a lot of power for any individual to have<br />

- especially one who is appointed, rather<br />

than elected.<br />

The situation in SA is a little different<br />

from that in some other states, where<br />

directions have been issued by Health<br />

Ministers under Public Health Acts.<br />

Some of the steps taken by the Federal<br />

Government have also been unexpected,<br />

including the convening of the ‘National<br />

Cabinet’ - a body whose powers, and<br />

decisions, have started to come under<br />

scrutiny, with the Administrative Appeals<br />

Tribunal recently finding that the body is<br />

not in fact a committee of federal cabinet.<br />

That decision has consequences not<br />

only in the context of the Freedom of<br />

Information matter in which it was made,<br />

but may have broader ramifications on the<br />

impact of decisions made by that body.<br />

Limits on liberties and democratic<br />

principles will generally be accepted as<br />

a short term measure and where they<br />

are reasonable and proportionate, but<br />

all around the country, many are now<br />

beginning to query whether current<br />

approaches to managing public movement<br />

in light of the pandemic are, or are still,<br />

the right ones. Emergency Management<br />

legislation is a useful and necessary<br />

tool, but - as is also the case with other<br />

legislative regimes - it’s appropriate to<br />

regularly check if it is serving its intended<br />

purpose, or indeed, whether its current<br />

use is in accordance with that aim. The<br />

question now being asked by increasingly<br />

more people is at what point should we say<br />

that the situation has stabilized enough for<br />

us move away from a state of ‘emergency’,<br />

and return to a system where proper<br />

scrutiny and accountability is applied to<br />

decisions made by our elected officials,<br />

rather than delegated authorities? B<br />

<strong>September</strong> <strong>2021</strong> THE BULLETIN 5

EXECUTIVE POWER<br />

THE MARCH OF EXECUTIVE<br />

AUTHORITY HIGHLIGHTS<br />

FRAGILITY OF DEMOCRACY<br />

MORRY BAILES AM, SENIOR LAWYER & BUSINESS ADVISOR, TINDALL GASK BENTLEY<br />

As lawyers we spend a lot of time<br />

talking up the importance of the<br />

independence of the judiciary. It is indeed<br />

critically important, so we are not wrong<br />

in our obsession with it. An erosion of<br />

independence in the judiciary is often the<br />

first sign a democracy has lost its way. Take<br />

Hong Kong as a current example. How<br />

long can eminent foreign judges continue<br />

to sit comfortably on its Apex court, when<br />

it is now quite clear that there is political<br />

interference in the selection of the judiciary<br />

at other levels.<br />

However, at times we dwell perhaps<br />

too exclusively on this admittedly most<br />

vital of building blocks, perhaps at the<br />

expense of scrutinising our other arms of<br />

government.<br />

Our parliament is fairly easily<br />

understood fulfilling its legislative<br />

role. However executive government<br />

remains shrouded in a bit of mystery. It<br />

is opaque in a way the United States of<br />

America’s system is not, where executive<br />

power is so singularly concentrated in<br />

the office of President. Here executive<br />

power is wielded by some of the same<br />

parliamentarians that pass law, including<br />

the Attorney-General.<br />

The parliamentary convention in the<br />

British Parliament is that the Attorney-<br />

General of England and Wales has no<br />

position in Cabinet creating a degree of<br />

separation, answerable to the parliament<br />

rather than the cabinet. Not so in our<br />

country or in our state. The Attorney-<br />

General is at the heart of executive power.<br />

What is not at first apparent in the use<br />

of executive power is just how much is<br />

delegated through subordinate legislation.<br />

Parliament is responsible for delegating<br />

a great deal of its function, by necessity,<br />

to ministers who in turn rely on their<br />

agencies. The ‘trickle down’ effect is<br />

not widely understood nor is the extent<br />

of such delegations. All of a sudden,<br />

decisions are being made that parliament<br />

didn’t know about or hadn’t necessarily<br />

contemplated. Enter the era of rule by the<br />

executive, and a foreboding sense that the<br />

executive arm of government may have<br />

spread its tentacles so far that it is difficult<br />

to entirely comprehend or reign in.<br />

A current example arises from the<br />

Return to Work Act, introduced by the<br />

former ALP government and passed by<br />

the then parliament. It gave certain powers<br />

to the Minister for Industrial Relations, to<br />

makes changes to the Act’s impairment<br />

assessment guidelines.<br />

Following some judicial decisions<br />

involving interpretation of the Act and<br />

guidelines, the perception was that things<br />

had gone against the interests of Return<br />

to Work SA. The Minister for Industrial<br />

Relations indicated an intention or interest<br />

in changing the guidelines, perhaps to take<br />

away the disadvantage for Return to Work<br />

SA created by those judicial decisions,<br />

although that was not his stated intention.<br />

Instead, his intent was cloaked in more<br />

beguiling words:<br />

“to deliver greater clarity, consistency,<br />

and transparency, and to reflect relevant<br />

clinical developments. There are also<br />

corrections and clarifications proposed.”<br />

In spite of a sense of inequity about<br />

what the Minister for Industrial Relations<br />

may do, and opposition from parts of the<br />

legal profession and medical profession,<br />

the powers delegated to the Minister were<br />

not contained in a disallowable instrument.<br />

When parliamentarians had a look at what<br />

they had enacted, they discovered that<br />

as the powers were not contained in the<br />

disallowable instrument, parliament had no<br />

role; it could not move a motion to prevent<br />

the minister using his delegated power.<br />

Despite Labor’s attempt to rectify a situation<br />

(which it largely created) by introducing<br />

a Bill to mandate that such changes be<br />

made via Regulation, the Minister recently<br />

gazetted the changes with all but the stroke<br />

of his pen. All because parliament gave<br />

away its power to a member of executive<br />

government, and lost control.<br />

Needless to say that example is one of<br />

thousands upon thousands of delegations<br />

by way of subordinate legalisation to the<br />

executive arm.<br />

No example though better illustrates<br />

the true power of the executive than<br />

what has happened from the start of the<br />

COVID pandemic. Parliament has quite<br />

literally allowed our freedom of movement,<br />

our freedom of association, our liberty, and<br />

an accounting of our daily whereabouts<br />

to be decided by government agencies.<br />

The Commissioner of Police has certain<br />

6<br />

THE BULLETIN <strong>September</strong> <strong>2021</strong>

EXECUTIVE POWER<br />

powers as does the Chief Public Health<br />

Officer. Through a matrix of primary and<br />

subordinate legislation and instruments we<br />

are captured and controlled by unelected<br />

largely unaccountable people. None of this<br />

should take from their efforts. Additionally,<br />

it is parliament that did this and we elected<br />

its members. Yet the fact remains that the<br />

power delegated to the executive is vast.<br />

Analysing bills before parliament these<br />

days is a three part process. What is in the<br />

primary bill, what is in the regulations and<br />

then the real devil in the detail, what is in<br />

the delegations? Often it is there that one<br />

realises a minister can do whatever she or<br />

he wishes.<br />

Back to COVID, the use of executive<br />

power can be argued to be a necessity due<br />

to the speed with which decisions need to<br />

be made. On the other hand the control<br />

over our daily lives by government agencies<br />

and their leaders is extraordinary. It goes<br />

without saying that the power must be<br />

exercised with bona fides and the courts<br />

stand by to curtail these uses of power if<br />

they are beyond power. Yet it is a very big<br />

ask for a private citizen at personal expense<br />

to test such pervasive executive decrees.<br />

Odds are that they are lawful anyway.<br />

Moreover, the raison d’être behind an<br />

executive use of power may be singular<br />

(for instance to quell a disease) and have<br />

no regard for any consequential loss of<br />

rights. So it was when Western Australians<br />

were compelled to use QR codes after<br />

receiving assurances from their Premier<br />

and Health Minister that the data would<br />

be sacrosanct and used exclusively for<br />

health purposes, only to have police<br />

unapologetically seize the data as evidence<br />

in a murder investigation. So much for the<br />

oft employed lines of self justification, ‘if<br />

you only knew what we knew’ and ‘trust<br />

the system’.<br />

For the executive the ends so often<br />

justify the means, whereas the judicial arm<br />

of government is much more likely to<br />

take exception to that approach. However<br />

good faith immunities have made it<br />

difficult or impossible to resort to the<br />

courts for remedies.<br />

What the growth of executive power<br />

has meant for the legal profession has been<br />

profound. Administrative law has become<br />

a growth area. Administrative tribunals<br />

proliferate, and statutory interpretation is<br />

what the law is now mostly about.<br />

It has become necessary for superior<br />

courts to analyse what species of executive<br />

power is being utilised, and its validity.<br />

Traditionally we have had two sources<br />

of executive power in our country, by<br />

prerogative or by statute. Edmund Barton<br />

in Adelaide in 1897 explained executive<br />

power as:<br />

‘primarily divided into two classes:<br />

those exercised by the prerogative ...<br />

and those which are ordinary Executive<br />

Acts, where it is prescribed that the<br />

Executive shall act in Council.’ 1<br />

Born from those constitutional<br />

conventions was S61 of the Australian<br />

Photo: REUTERS / Sandra Sanders - stock.adobe.com.<br />

Constitution which seeks to describe the<br />

executive powers of the Commonwealth<br />

(though not exhaustively as remarked upon<br />

by Sir Anthony Mason), excluding those<br />

still held by the states. S61 reads as follows:<br />

‘The executive power of the<br />

Commonwealth is vested in the Queen<br />

and is exercisable by the Governor-<br />

General as the Queen’s representative,<br />

and extends to the execution and<br />

maintenance of this Constitution, and<br />

of the laws of the Commonwealth.’<br />

Particularly at the Federal level the<br />

development of jurisprudence about<br />

executive power has been evolving since<br />

Federation. The use of executive power<br />

in borders cases has been central to that<br />

evolution including the Federal Court in<br />

Ruddock v Vadarlis. 2<br />

Former Chief Justice Robert French<br />

AC summarised the recent state of<br />

executive power in Australia in a paper for<br />

the University of Western Australia Law<br />

Review in this this way:<br />

‘There are, no doubt from an academic<br />

perspective, many unanswered questions<br />

about the scope of Commonwealth<br />

executive power in Australia and<br />

perhaps also the scope of the executive<br />

power of the States. Some of them<br />

may give rise to anxiety about future<br />

directions. The judiciary is unlikely to<br />

provide a comprehensive answer in any<br />

one case. The development of principle<br />

will proceed case-by-case.’ 3<br />

<strong>September</strong> <strong>2021</strong> THE BULLETIN 7

EXECUTIVE POWER<br />

However, for most Australians the<br />

evolution of executive power in our<br />

country is not likely very well understood.<br />

What is understood are the daily<br />

experiences citizens have with the myriad<br />

of executive decisions that are made, daily<br />

impacting their lives.<br />

If we go back to Hong Kong for<br />

a moment, the real problem there has<br />

been an executive doing the bidding of<br />

Beijing. The Legislative Council there is<br />

really wall paper. The power is held by a<br />

Beijing appointed executive, and now that<br />

Beijing has started to flex muscle it is really<br />

the end of a democratic, self-governing<br />

territory. It brings meaning to<br />

Sir Owen Dixon’s words,<br />

‘History and not only ancient history,<br />

shows that in countries where<br />

democratic institutions have been<br />

unconstitutionally superseded, it has<br />

been done not seldom by those holding<br />

the executive power.’ 4<br />

In the case of our close ally the United<br />

States, President Obama governed largely<br />

by executive decree as did President Trump<br />

and President Biden appears to be going<br />

down the same route. Executive power<br />

is necessary but to what extent is it being<br />

used to navigate around the legislature?<br />

In spite of the fears of many the U.S.<br />

has managed perfectly well to keep its<br />

Presidents acting constitutionally, so the<br />

exercise of executive power, however hard<br />

it may be to define at times, must also be<br />

seen to operate within the constraints of a<br />

society that respects the rule of law and is<br />

ring-fenced by the judiciary.<br />

Thus in spite of the awesome power<br />

of the executive during COVID it has<br />

been utilised with the best intentions in a<br />

country that is underpinned by the rule of<br />

law. It would create greater comfort for<br />

many however if the parliament would not<br />

take, at times, such a ‘hands off ’ approach.<br />

That said, executive power is critical to<br />

governance of Australia, and of each of<br />

its States, and is as ancient in origin as it is<br />

illusive to define.<br />

As our populations grow, as governance<br />

becomes more complex, and as our<br />

parliaments grapple with globalisation in<br />

the modern age, one certainty is the growth<br />

of the executive arm of government.<br />

It is critically important that this not go<br />

unchecked. For much of the opening<br />

chapters of COVID, parliaments were in<br />

recess. The Biosecurity Act was used to<br />

wield far reaching executive power, as was<br />

our State’s Emergency Management Act,<br />

together with a raft of COVID specific<br />

primary and subordinate legislation. In<br />

a head nod to these unparalleled powers<br />

the Chief Public Health Officer let slip<br />

last year that she may wish to retain QR<br />

tracking for reasons other than COVID.<br />

The infection of unfettered power might<br />

be the lasting legacy of COVID long after<br />

the virus itself has been quelled.<br />

It is necessary to remind ourselves,<br />

the citizenry, and most importantly our<br />

parliamentarians, that executive power<br />

used at these ‘shock and awe’ levels is<br />

extraordinary and not the norm. For<br />

parliament to be at times incapable of<br />

controlling the power it has delegated<br />

does not rest easily with our concept of<br />

the separation of powers. Not only do the<br />

powers require independence they also<br />

require balance. When police and military<br />

are in charge and able to detain us and<br />

restrain us, the grant of those powers must<br />

be temporary or we tempt the creation of<br />

a society long rejected by Australians.<br />

The march of executive supremacy,<br />

as some have described, has reached an<br />

interesting juncture in Australia. It is vital<br />

that we vigilantly measure that march<br />

and ensure supremacy remains firstly<br />

vested with parliaments. As lawyers our<br />

understanding of these concepts, central<br />

to our stable democracy and grounding<br />

the rule of law, mean that we have a<br />

responsibility greater than others to<br />

protect and guard the fragility of a system<br />

that should not be permitted to tilt to far<br />

toward rule only by executive order. B<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 Official Report of the Australasian Federal<br />

Convention Debates, Adelaide, 19 April 1897<br />

2 Vol 43(2)<br />

3 [2001] FCA 1329<br />

4 Australian Communist Party v Commonwealth<br />

(1951) 83 C<strong>LR</strong> 1<br />

EXPERT<br />

FORENSIC<br />

REPORTS &<br />

LITIGATION<br />

SUPPORT<br />

Benefit from over 30 years<br />

experience in engineering, road<br />

and workplace safety, with<br />

in-depth incident investigation.<br />

Court tested to the highest<br />

levels in all jurisdictions.<br />

• Accident investigation<br />

• 3D incident reconstructions<br />

• Forensic & safety engineering<br />

• Transport & workplace safety<br />

INSIGHT • DETAIL • CLARITY • RELIABILITY<br />

8<br />

THE BULLETIN <strong>September</strong> <strong>2021</strong><br />

To discuss your needs call:<br />

0418 884 174<br />

george@georgerechnitzer.com.au<br />

www.georgerechnitzer.com.au

FROM THE CONDUCT COMMISSIONER<br />

Poaching clients from<br />

your former firm<br />

GREG MAY, LEGAL PROFESSION CONDUCT COMMISSIONER<br />

It is of course common for a lawyer to<br />

move from one firm to another. The<br />

question often arises as to whether it is<br />

appropriate for a lawyer to attempt to<br />

“poach” a client from his or her former<br />

firm – that is, to get the client to terminate<br />

the instructions of the former firm and<br />

to instead instruct the lawyer’s new firm.<br />

Indeed, that will often be a substantial<br />

reason for the new firm employing the<br />

lawyer – because of the likelihood that<br />

at least some of the lawyer’s clients will<br />

follow him or her to the new firm.<br />

So, how proactive can the lawyer be in<br />

attempting to induce a client to follow? I<br />

think everyone would accept that a client<br />

who finds out about the lawyer changing<br />

firms from, for example, a promotional<br />

advertisement in the paper, and who<br />

unilaterally decides to change firms, is<br />

entitled to do so and the lawyer cannot<br />

be criticised. But what happens when<br />

the lawyer starts contacting clients to<br />

encourage them to change firms?<br />

This issue was considered many years<br />

ago in a Supreme Court decision by<br />

Justice Perry 1 . While the case itself dealt<br />

with disciplinary proceedings against a<br />

chiropractor, Perry J made the following<br />

observations in relation to the legal<br />

profession (at [51] to [53]):<br />

In the context, for example, of the legal<br />

profession, it is unlikely that a charge of<br />

unprofessional conduct would these days be<br />

sustained simply on the basis that a practitioner<br />

had endeavoured to induce customers to engage<br />

him or her, rather than remain a client of<br />

another practitioner.<br />

There is much movement of practitioners in<br />

and out of legal firms, and it is a common<br />

occurrence for practitioners who leave a firm to<br />

take up practice elsewhere, to draw with them<br />

clients of the firm which they have left. This is<br />

an unexceptional and everyday experience.<br />

Even the regular monthly Bulletin published<br />

by the Law Society of South Australia<br />

makes public announcements of movements<br />

of practitioners from one practice situation to<br />

another. No doubt clients of a former practice<br />

who may read such publications may be induced<br />

to follow a practitioner to a new practice.<br />

And that was 17-plus years ago – if<br />

Perry J thought then that there was “much<br />

movement of practitioners in and out of<br />

legal firms”, there can be no doubt that<br />

that is the case now!<br />

Having said that, from a conduct<br />

point of view there is still a right way and<br />

a wrong way to go about attempting to<br />

induce a client to move firms. Professor<br />

Dal Pont says 2 that the following<br />

requirements apply to any such contact:<br />

• the departing lawyer should first<br />

inform the firm of her or his proposed<br />

departure, so that it may meet with<br />

and/or write to clients informing<br />

them of any new arrangements for the<br />

conduct of their matters;<br />

• any contact by the departing lawyer<br />

should not deprecate the firm or its<br />

members;<br />

• the departing lawyer should in no way<br />

suggest or indicate that clients are<br />

obliged to instruct the new firm, nor<br />

should the departing lawyer undermine<br />

existing lawyer-client relationships<br />

between the firm and its clients;<br />

• if a client expresses a wish to transfer<br />

instructions from the firm to the<br />

departing lawyer, the departing lawyer<br />

should inform the client of his or her<br />

responsibility to negotiate the terms of<br />

the transfer, including the requirement<br />

either to pay all outstanding costs<br />

and disbursements or to secure the<br />

firm’s entitlements to costs and<br />

disbursements.<br />

He goes on to say that the firm should<br />

then facilitate the transfer of files, subject<br />

to the payment of any such firm’s fees and<br />

disbursements.<br />

In my view, particularly if the<br />

departing lawyer is a partner at the old<br />

firm, he or she should not contact any<br />

clients in this way until after having left the<br />

firm, unless his or her old firm consents<br />

to that contact prior to departure. Until<br />

the departing lawyer has left the firm,<br />

he or she has certain duties to the firm<br />

that in my view would be breached if the<br />

departing lawyer is attempting to induce a<br />

client to leave that firm while still at that<br />

firm.<br />

Importantly, Professor Dal Pont also<br />

says that “any valid contractual restriction on<br />

solicitation of a client contained in the departing<br />

lawyer’s contract of employment or partnership<br />

agreement with her or his former firm must be<br />

adhered to”.<br />

The UK Supreme Court has recently<br />

ruled 3 that a type of non-compete<br />

undertaking of a solicitor was not given<br />

in the course of practice because it was a<br />

business arrangement. The Court made<br />

the following observations at [122]:<br />

A business arrangement between two law<br />

firms is not the sort of work which solicitors<br />

undertake as part of their ordinary professional<br />

practice. It is a business matter, even if the<br />

business in question relates to the provision of<br />

professional services.<br />

It was therefore held that the inherent<br />

supervisory jurisdiction of the Supreme<br />

Court to regulate the conduct of solicitors<br />

did not govern its enforceability. The<br />

Court was of the view that the contractual<br />

law doctrine of restraint of trade would<br />

apply to such agreements so that only<br />

reasonable restraints could be enforced.<br />

Another interesting aspect of<br />

the judgment is the finding that the<br />

supervisory jurisdiction does not apply<br />

directly to corporate law firms as they<br />

are not officers of the court. This creates<br />

difficulties in relation to undertakings<br />

given on behalf of corporate firms, and<br />

the Court expressed the hope that the UK<br />

Parliament might address this lacuna. B<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 Judge v Chiropractors Board of South Australia [2004]<br />

SASC 214.<br />

2 Dal Pont, Lawyers Professional Responsibility,<br />

7 th edition at [20.65]<br />

3 Harcus Sinclair LLP v Your Lawyers Ltd [<strong>2021</strong>]<br />

UKSC 32<br />

<strong>September</strong> <strong>2021</strong> THE BULLETIN 9

FEATURE<br />

Time to take lawmaking seriously:<br />

the problem of delegated<br />

legislation in South Australia<br />

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR LORNE NEUDORF, ADELAIDE LAW SCHOOL, UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE<br />

The Parliament of South Australia plays<br />

a key constitutional role as the state’s<br />

lawmaker-in-chief, operating as the forum<br />

for the exercise of legislative power in a<br />

democratic society founded on the rule<br />

of law. Since its establishment in 1857,<br />

the South Australian Parliament has been<br />

at the cutting edge of some of the most<br />

important political and social changes in<br />

Australia and indeed the world. It enacted<br />

legislation that made South Australia the<br />

first colonial government to grant women<br />

both the right to vote and stand for<br />

election (1895) and the first Australian state<br />

to decriminalise sexual activity between<br />

consenting males (1975), for which the<br />

criminal law had previously prescribed<br />

severe punishments including death, life<br />

imprisonment in solitary confinement, hard<br />

labour and whipping.<br />

Because of the important interests<br />

at stake in lawmaking, the parliamentary<br />

process is designed to help lawmakers<br />

appreciate the implications of proposed<br />

legislation. Significant measures of<br />

accountability and transparency are part of<br />

the legislative process that must be followed<br />

before a bill can become law. The process<br />

requires public readings, the publication of<br />

draft legislative text, open debate by elected<br />

members that represent constituencies<br />

across the state, committee study where<br />

the views of experts and citizens are<br />

expressed, and the recorded votes of all<br />

members in each of the two Houses. The<br />

legislative process not only helps lawmakers<br />

better understand their legislative choices,<br />

it safeguards the legitimacy of Parliament<br />

as lawmaker for a diverse society. It also<br />

enhances the quality of legislative outcomes<br />

by subjecting policy and legislative text to<br />

multiple rounds of scrutiny from diverse<br />

perspectives, including those of members<br />

of different political parties that collectively<br />

represent a cross-section of the community.<br />

Over the past few decades, there has<br />

been a shift away from parliamentary<br />

lawmaking to an alternative lawmaking<br />

process. This trend threatens parliament’s<br />

role as lawmaker-in-chief and undermines<br />

democratic values and institutions. It<br />

can be seen throughout Australia and in<br />

other Westminster parliaments including<br />

those in Canada, the United Kingdom and<br />

New Zealand. This alternative form of<br />

lawmaking side-steps the parliamentary<br />

process by having the executive branch of<br />

government make laws directly. Such laws<br />

have the same legal force as legislation<br />

enacted by parliament. It occurs through<br />

the parliamentary delegation of legislative<br />

powers. Almost all bills include significant<br />

delegations that permit the executive to<br />

make delegated legislation directly. These<br />

delegations may allow the executive to<br />

fill in the details of a statutory scheme,<br />

but they can also be drafted in sweeping<br />

terms that authorise the executive to<br />

make and implement significant policy<br />

choices. Bills often allow the executive to<br />

make laws that are ‘necessary or expedient<br />

for the purposes of this Act’, providing<br />

little guidance on the kinds of delegated<br />

laws that might later be made and little<br />

opportunity for a reviewing court to<br />

impose meaningful limits on the scope of<br />

the delegated power.<br />

South Australia is no exception to the<br />

general trend. Delegated legislation is the<br />

principal way that new law is made in the<br />

state. Last year, 88% of all new laws made<br />

were delegated laws. 1 While the pandemic<br />

has prompted an even greater reliance on<br />

delegated legislation to respond quickly<br />

to changing circumstances, the number<br />

of delegated laws overshadowed that of<br />

primary legislation in South Australia<br />

well before COVID-19: over the past<br />

three years, 86% of all new laws made in<br />

the state were in the form of delegated<br />

legislation. In terms of the total number<br />

of pages of legislative text, delegated<br />

legislation comprised nearly 70% of the<br />

statute book over the same period of time.<br />

To be made, delegated laws need to<br />

follow only a cursory process set out in the<br />

Subordinate Legislation Act 1978. The Act<br />

imposes none of the robust accountability<br />

and transparency measures found in<br />

the ordinary parliamentary process: for<br />

delegated legislation, there is no public<br />

reading, no publication of draft legislative<br />

text, no open debate, no committee study<br />

to hear from experts and citizens, and no<br />

recorded vote. In fact, there is no vote at<br />

all because lawmaking decisions are made<br />

in secret, behind closed doors. Discussions<br />

and deliberations by the cabinet relating<br />

to delegated legislation are confidential<br />

and protected by legal privilege. The Act<br />

imposes no requirements for consultation<br />

of any kind before new delegated laws are<br />

made. Details of any consultation carried<br />

out are not published. It is not possible to<br />

see what information was relied upon by<br />

the executive in making legislative choices<br />

or who might have influenced them. Was<br />

the information fair and accurate? Which<br />

individuals and groups were consulted?<br />

Were any concerns raised? If so, were<br />

the concerns addressed? Under the Act,<br />

none of these questions need to be<br />

answered. In making delegated legislation,<br />

the executive is not required to publish a<br />

statement to explain the purpose of the<br />

new law, or even explain why a change<br />

to the law might be desirable. Without<br />

this context, it is sometimes difficult to<br />

work out whether a delegated law has a<br />

rational purpose and whether its text is<br />

connected to that purpose. And despite<br />

the Act imposing a default rule of four<br />

months’ commencement for delegated<br />

legislation, almost all new laws invoke an<br />

exemption that permits them to come<br />

into force immediately, on the very day on<br />

which they are made. In South Australia,<br />

delegated legislation is made by the<br />

government as a fait accompli.<br />

The only parliamentary oversight<br />

of delegated legislation takes place in<br />

the over-burdened and under-resourced<br />

Legislative Review Committee. 2 Consisting<br />

of six members drawn from both Houses,<br />

the Committee scrutinises all ‘rules,<br />

regulations and by-laws’ that are required<br />

to be tabled in Parliament – a Herculean<br />

task if there ever was one. Last year, more<br />

than 1,400 pages of delegated legislation<br />

were made in 324 different instruments,<br />

which does not include all the new bylaws<br />

made by the state’s 68 local councils or<br />

rules of court that are also scrutinised<br />

10<br />

THE BULLETIN <strong>September</strong> <strong>2021</strong>

FEATURE<br />

by the Committee. With the support of<br />

one secretary in relation to its scrutiny<br />

function, the Committee is expected<br />

to examine each and every line of this<br />

morass of often highly technical legislative<br />

text against 38 different considerations,<br />

including: whether it infringes the<br />

separation of powers; is inconsistent with<br />

the rule of law; is in accordance with its<br />

enabling legislation and the requirements<br />

of any other Act; has certainty of meaning<br />

and operation; fails to protect privacy;<br />

authorises the use of force, detention<br />

or search and seizure; has retrospective<br />

effect; imposes strict or absolute liability;<br />

reverses the evidential burden of proof;<br />

abrogates privileges including the privilege<br />

against self-incrimination; interferes with<br />

property rights; intends to bring about<br />

radical changes in relationships or attitudes<br />

of people in an aspect of the life of the<br />

community; has unforeseen consequences;<br />

is inconsistent with natural justice; has<br />

costs that outweigh the benefits; imposes<br />

excessive fees and charges; authorises<br />

excessive discretionary decisions; provides<br />

adequate notice to persons who may be<br />

affected; and restricts independent merits<br />

review of discretionary decisions affecting<br />

rights, interests or obligations.<br />

In effect, the Committee is tasked<br />

with carrying out the entire parliamentary<br />

process for all delegated legislation subject<br />

to scrutiny, giving it one of the most<br />

critical roles in upholding democratic<br />

values for most laws made in South<br />

Australia. Inevitably, it is snowed under<br />

by a ceaseless flurry of new delegated<br />

legislation. While the Committee does<br />

what it can within its situational and<br />

operational constraints (including<br />

occasionally introducing notices of motion<br />

to disallow delegated legislation), it is<br />

ultimately hamstrung by the Subordinate<br />

Legislation Act 1978’s paper-thin process for<br />

making delegated legislation that fails to<br />

impose adequate and meaningful controls<br />

on executive lawmaking. Under the Act’s<br />

framework and with few resources, it is<br />

not possible for the Committee to achieve<br />

the minimum levels of accountability<br />

and transparency for lawmaking that are<br />

expected in a democratic society.<br />

Three changes are urgently needed to<br />

address this problem. First, the scheme<br />

for making delegated legislation in South<br />

Australia under the Subordinate Legislation<br />

Act 1978 needs a major overhaul to beef<br />

up the standards and requirements for<br />

making delegated laws. The delegated<br />

lawmaking schemes at the Commonwealth<br />

and in other jurisdictions provide useful<br />

comparative guidance on these necessary<br />

reforms. Second, a specialist bills committee<br />

is needed to identify and challenge<br />

inappropriate delegations of legislative<br />

power. Parliament must reassert itself as the<br />

chief lawmaking institution and prevent the<br />

continued erosion of its legislative powers<br />

and role. If Parliament is not willing to act,<br />

courts may have to. In a recent judgment<br />

of the Supreme Court of Canada, Justice<br />

Côté would have held certain legislative<br />

delegations unconstitutional on the basis<br />

that they conferred ‘inordinate discretion in<br />

the executive with no meaningful checks’<br />

on their use. 3 The statute at issue in that<br />

case ‘knows no bounds’ as it ‘set forth a<br />

wholly-unfettered grant of broad discretion’<br />

to the executive. 4 In Justice Côté’s view,<br />

the delegations infringed the constitutional<br />

principles of parliamentary sovereignty, the<br />

separation of powers and the rule of law<br />

and were ‘so inconsistent with our system<br />

of democracy that they are independently<br />

unconstitutional’. 5 Third, the Committee<br />

is in desperate need of additional staffing<br />

resources to allow it to effectively provide<br />

parliamentary oversight of the most<br />

significant source of law in South Australia.<br />

Again, comparative benchmarking against<br />

the Commonwealth and other jurisdictions<br />

will indicate the appropriate level of<br />

resources that are needed.<br />

The Parliament of South Australia’s<br />

traditional role of providing a democratic<br />

forum for the contestation of ideas<br />

and perspectives is at risk because of<br />

an alternative lawmaking process that is<br />

used to make the vast majority of laws<br />

outside Parliament. While the trend toward<br />

delegation may be unstoppable, reforms<br />

can establish an appropriately robust<br />

delegated lawmaking process that meets<br />

requisite standards of accountability and<br />

transparency for lawmaking in a democratic<br />

society. Effective parliamentary oversight<br />

through an appropriately resourced<br />

committee is also essential to maintain<br />

the constitutional role of Parliament as<br />

lawmaker-in-chief and ultimately the<br />

legitimacy of delegated laws. Unfortunately,<br />

the Parliament of South Australia has fallen<br />

behind other jurisdictions. The erosion<br />

of Parliament’s place must be reversed. It<br />

must reassert itself and reinvigorate the<br />

process by which delegated legislation<br />

is made and scrutinised. But why strive<br />

for the bare minimum or merely seek to<br />

catch-up with others? Parliament should<br />

restore its once-proud tradition to lead<br />

the way in the promotion of democratic<br />

values. Two inquiries presently underway<br />

– the inquiry of the Effectiveness of<br />

the Current System of Parliamentary<br />

Committees parliamentary committee<br />

and the South Australian Productivity<br />

Commission’s inquiry into the reform of<br />

the state’s regulatory framework – have the<br />

potential to initiate the process of bringing<br />

about positive change. While important,<br />

the challenges of delegated legislation are<br />

unlikely to be fully addressed by the reform<br />

recommendations of any single inquiry. To<br />

show leadership, more fundamental change<br />

is needed. It will require a wholesale reconceptualisation<br />

of how we make laws. B<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 See Lorne Neudorf, ‘Strengthening the Scrutiny<br />

of Delegated Legislation’ (Presentation to the<br />

South Australian Legislative Review Committee,<br />

2 February <strong>2021</strong>) slides and Hansard transcript<br />

available at https://www.parliament.sa.gov.<br />

au/Committees/lrc (located in the sub-folder<br />

‘1 Committee Information’ / ‘Committee<br />

Performance’).<br />

2 It should be noted that the Committee is<br />

restricted by the Subordinate Legislation Act 1978<br />

to the kinds of instruments that it can scrutinise.<br />

Such instruments must be called a ‘regulation,<br />

rule or by-law’: s 4 ‘regulation’.<br />

3 References re Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act,<br />

<strong>2021</strong> SCC 11 at [223].<br />

4 Ibid, [230], [240].<br />

5 Ibid, [241].<br />

<strong>September</strong> <strong>2021</strong> THE BULLETIN 11

FEATURE<br />

COVID SAFE CHECK-IN: USE<br />

BEYOND CONTACT TRACING?<br />

RAFFAELE PICCOLO, BARRISTER, ANTHONY MASON CHAMBERS<br />

Since December, 2020 the use of COVID<br />

SAfe Check-In has been mandatory at<br />

most venues in South Australia. Venues are<br />

required to display posters with a unique<br />

QR code (which links to COVID SAfe<br />

Check-In). In turn, patrons are required<br />

to register their attendance at such venues<br />

using COVID SAfe Check-In (accessible<br />

via the QR code displayed). 1 Refusal or<br />

failure to comply with this requirement<br />

constitutes an offence, and if prosecuted,<br />

attracts a maximum penalty of a fine or<br />

imprisonment. 2<br />

The stated purpose for mandating<br />

the use of COVID SAfe Check-In is to<br />

improve contact tracing efficiency, so that<br />

contact tracers, ‘can immediately, 24/7, go<br />

straight to that database instead of waiting until<br />

the next day to get hold of a business and to get<br />

those details’. 3<br />

Since the introduction of COVID<br />

SAfe Check-In, the State Government has<br />

repeatedly given a number of assurances<br />

regarding the data collected via COVID<br />

SAfe Check-In. These assurances have<br />

included the following. First, the data<br />

collected is stored in a government secured<br />

and encrypted database. Second, the data is<br />

only to be retained for a period of 28 days,<br />

and will only be released to SA Health for<br />

official contact tracing purposes. Third,<br />

if the data is used for contact tracing, the<br />

data is only to be retained for as long as<br />

necessary for those purposes, and no longer<br />

than the COVID-19 pandemic remains. 4<br />

The mandatory use of COVID<br />

SAfe Check-In is a reasonable and<br />

proportionate means to facilitating<br />

efficient contact tracing. This is not<br />

disputed. However, given the potential<br />

for the use of the data collected via<br />

COVID SAfe Check-In for purposes<br />

other than contact tracing (to lessen the<br />

transmission of COVID-19), more than<br />

simple assurances are required. Legislative<br />

safeguards to the same effect are necessary.<br />

The need for legislative safeguards<br />

remains, despite the refusal of SA Health<br />

to disclose similar information when<br />

requested by police in November, 2020.<br />

At this time, police were investigating an<br />

allegation that a person had lied during<br />

12<br />

THE BULLETIN <strong>September</strong> <strong>2021</strong><br />

an initial interview with SA Health about<br />

his employment at Woodville Pizza Bar<br />

(the information the subject of this<br />

interview was ‘central’ to the decision to<br />

impose the ‘circuit breaker’ lockdown in<br />

South Australia in November, 2020). 5 SA<br />

Health reportedly refused to disclose any<br />

information regarding the interview on the<br />

basis of ‘patient privilege’ (also described<br />

as ‘patient-doctor confidentiality’). 6<br />

Little comfort can be taken from this<br />

example. First, the information collected<br />

via COVID SAfe Check-In is stored in a<br />

database maintained by the Department of<br />

the Premier and Cabinet (not SA Health).<br />

SA Health is only provided access to data<br />

as and when necessary to undertake contact<br />

tracing. 7 Second, the refusal on the part of<br />

SA Health was reported to be in response<br />

to a request from police, rather than under<br />

compulsion of a warrant or subpoena (with<br />

which non-compliance might amount to<br />

contempt). The basis upon which such a<br />

warrant, or subpoena, might be resisted, are<br />

discussed further below.<br />

In any event, concerns regarding the<br />

lack of legislative safeguards are evermore<br />

paramount now, approximately nine<br />

months after the introduction of COVID<br />

SAfe Check-In, for three reasons. First,<br />

recent reports that law enforcement<br />

authorities in other jurisdictions have<br />

accessed, or attempted to access, similar<br />

data for purposes other than contact tracing<br />

(using a warrant). 8 Second, moves by<br />

other jurisdictions to introduce legislative<br />

safeguards to better ensure that such data is<br />

not used for any purpose other than contact<br />

tracing. 9 Third, the recent expansion of the<br />

use of COVID SAfe Check-In to public<br />

transport, with the implication that a greater<br />

amount of data will be collected. 10<br />

POWER TO ISSUE DIRECTIONS<br />

Pursuant to the Emergency Management<br />

Act 2004 (SA) (‘Emergency Management Act’),<br />

a declaration of a major emergency (‘the<br />

declaration’) in relation to the COVID-19<br />

pandemic has been in effect in South<br />

Australia since 22 March, 2020. 11 The effect<br />

of the declaration is to vest in the State<br />

Co-ordinator (the Commissioner of Police)<br />

a number of responsibilities and powers,<br />

including the power to direct or require<br />

persons to do or cause to be done any of<br />

a number of things. 12 Most relevantly, the<br />

State Co-ordinator can require a person<br />

to furnish such information as may be<br />

reasonably required in the circumstances. 13<br />

REQUIREMENT TO REGISTER ATTENDANCE<br />

USING COVID SAFE CHECK-IN<br />

During the period of the declaration,<br />

the State Co-ordinator has issued a number<br />

of directions. On 1 December, 2020,<br />

the State Co-ordinator issued Emergency<br />

Management (Public Activities No 13)<br />

(COVID-19) Direction 2020 (‘Public Activities<br />

No 13 Direction’). Unlike predecessor<br />

directions, 14 Public Activities No 13 Direction<br />

included a requirement that any person<br />

attending at a relevant place had to<br />

use their ‘best endeavours in all of the<br />

circumstances’ to ensure that their ‘relevant<br />

contact details’ 15 were captured by the<br />

approved contact tracing system 16 (defined<br />

as COVID SAfe Check-In, or ScanTek, or<br />

another system approved by the State Coordinator).<br />

17 The requirement that a person<br />

register their attendance at a venue using<br />

COVID SAfe Check-In has remained a<br />

component in replacement directions since<br />

issued by the State Co-ordinator. 18<br />

INADEQUACY OF CURRENT PROTECTIONS<br />

When issued, Public Activities No 13<br />

Direction did not include any provision<br />

which restricted the use or disclosure of<br />

the information collected by COVID<br />

SAfe Check-In. It was not until 8 April,<br />

<strong>2021</strong>, that provisions were implemented<br />

regarding the use of data collected via<br />

COVID SAfe Check-In. These provisions<br />

provide the following. First, any data<br />

collected pursuant to any directions issued<br />

under the Emergency Management Act is only<br />

allowed to be used for the purpose of<br />

contact tracing in relation to COVID-19,<br />

or managing the COVID-19 pandemic.<br />

Second, any data retrieved from the<br />

database and given to SA Health for the<br />

purpose of contact tracing is taken to be

FEATURE<br />

information protected by the Health Care<br />

Act 2008 (SA) (‘Health Care Act’). 19<br />

It might be inferred that the purpose<br />

of these provisions was to purportedly<br />

respond to concerns regarding the<br />

potential use of the data collected via<br />

COVID SAfe Check-In for purposes other<br />

than contact tracing. 20 In any event, as<br />

outlined below, the provisions contained<br />

in the directions appear to be ineffectual in<br />

meeting any such objective.<br />

DISCLOSURE REQUIRED BY A COURT OR<br />

TRIBUNAL OR AUTHORISED BY LAW<br />

First, while the State Co-ordinator<br />

can issue directions to require a person to<br />

furnish information it is not clear that the<br />

State Co-ordinator thereafter has a power<br />

to restrict the use of that information<br />

(such as data collected via COVID SAfe<br />

Check-In) by others for other purposes.<br />

Moreover, regardless of the effectiveness<br />

of such provisions, any purported<br />

restriction is clearly in conflict with the<br />

provisions of the Emergency Management<br />

Act regarding disclosure of information<br />

(with the effect that the provisions of the<br />

Act will prevail over the directions to the<br />

extent of any inconsistency).<br />

Section 31A of the Emergency<br />

Management Act prohibits the disclosure<br />

of information relating to the personal<br />

affairs of another that was obtained<br />

in the course of the administration or<br />

enforcement of that Act. Contravention<br />

of this prohibition constitutes an offence.<br />

It is this provision (along with the<br />

aforementioned assurances) on which the<br />

State Government has relied to assert that<br />

data collected via COVID SAfe Check-In<br />

is adequately protected from disclosure. 21<br />

However, reliance on this provision is<br />

misplaced; the provision explicitly allows<br />

for disclosure of information if required<br />

by a court or tribunal constituted by law. 22<br />

Thus, for example, the disclosure might<br />

be compelled pursuant to a subpoena,<br />

or a warrant. Failure to comply with a<br />

subpoena without lawful excuse constitutes<br />

a contempt of court, and is punishable by a<br />

fine or imprisonment (or both). 23<br />

A person might attempt to resist<br />

a subpoena, by seeking to have the<br />

subpoena set aside, 24 or asserting a claim<br />

to public interest immunity. 25 In relation<br />

to any claim of public interest immunity,<br />

the court is required to consider two<br />

conflicting aspects of the public interest:<br />

the harm that would be done by the<br />

production of data on the one hand, as<br />

against a consideration of whether the<br />

fair and efficient administration of justice<br />

would be frustrated or impaired by the<br />

non-disclosure on the other. 26 Similarly,<br />

in relation to a warrant, public interest<br />

immunity might be raised as basis for<br />

resisting seizure. 27 Moreover, a defendant<br />

might seek to convince a court to exercise<br />

the discretion to exclude lawfully obtained<br />

evidence on the basis of fairness (that<br />

admitting the evidence would be unfair<br />

to the defendant in the sense that the trial<br />

would be unfair). 28 Whether a subpoena<br />

is set aside, a claim for public interest<br />

immunity is upheld, or such data is<br />

otherwise excluded as evidence in any trial,<br />

will depend on the circumstances of the<br />

particular proceeding before a court; it will<br />

be decided on a case by case basis.<br />

Second, the inclusion of the reference<br />

to the Health Care Act does not appear to<br />

take the purported restriction regarding<br />

the disclosure of data collected via<br />

COVID SAfe Check-In much further.<br />

This Act prohibits the disclosure of<br />

personal information which was obtained<br />

in connection with the operation of<br />

this Act except to the extent a person<br />

is authorised or required to disclose<br />

that information. Contravention of this<br />

prohibition constitutes an offence. Again,<br />

however, the provision explicitly allows for<br />

disclosure of information as required or<br />

authorised by or under law. 29<br />

It’s noteworthy that the Western<br />

Australia State Government expressed<br />

similar concerns regarding the effectiveness<br />

of issuing directions to restrict the<br />

disclosure of information collected via<br />

SafeWA (an analogue of COVID SAfe<br />

Check-In). 30 These concerns served as a<br />

basis for the implementation of further<br />

legislative safeguards (as discussed below).<br />

ADMISSIBILITY OF DATA AS EVIDENCE IN<br />

ANY CIVIL PROCEEDING, OR CRIMINAL<br />

PROSECUTION<br />

Moreover, while the Emergency<br />

Management Act and the Health Care Act<br />

generally prohibit and criminalise the<br />

disclosure of information, such as data<br />

collected via COVID SAfe Check-In, this<br />

legislation does not render the information<br />

inadmissible as evidence in any civil<br />

proceeding, or criminal prosecution. Thus,<br />

even if information is disclosed to a law<br />

enforcement authority in contravention of<br />

the prohibition, the information remains<br />

admissible as evidence in any proceeding<br />

before a court notwithstanding that the<br />

disclosure might be illegal or unlawful,<br />

unless otherwise excluded by a court.<br />

In deciding whether to exercise the<br />

discretion to exclude illegally obtained<br />

evidence the court has to consider and<br />

weigh against each other two competing<br />

requirements of public policy. On the one<br />

hand there is the public interest in bringing<br />

to conviction those who commit criminal<br />

offences, and on the other hand there is<br />

the public interest in the protection of<br />

the individual from unlawful and unfair<br />

treatment. 31 Whether such information is<br />

excluded as evidence will depend on the<br />

circumstances of the particular proceeding<br />

before a court; it will be decided on a case<br />

by case basis.<br />

In summation, this legislative<br />

framework makes it difficult for South<br />

Australians to have absolute confidence<br />

in the assurances provided by the State<br />

Government regarding the storage, use<br />

and disclosure, of the data collected via<br />

COVID SAfe Check-In.<br />

Moreover, the potential access by<br />

law enforcement authorities to such data<br />

for purposes other than contact tracing<br />

(for general law enforcement activities) is<br />

not merely theoretical. Law enforcement<br />

authorities in Queensland, and Western<br />

Australia, have accessed such data, and in<br />

Victoria have requested access (but were<br />

refused, and advised to obtain a warrant). 32<br />

Moreover, the Acting Minister for Police<br />

in Victoria has publicly expressed his<br />

<strong>September</strong> <strong>2021</strong> THE BULLETIN 13

FEATURE<br />

reluctance to implement any legislation to<br />

guard against law enforcement authorities<br />

obtaining access to such data for use for<br />

purposes other than contact tracing. 33<br />

FORM OF ANY LEGISLATIVE SAFEGUARDS<br />

The legislation adopted by the<br />

Commonwealth, and Western Australia,<br />

serve as useful examples, of the form of<br />

legislative safeguards required in South<br />

Australia.<br />

At the Commonwealth level, there is<br />

the Privacy Amendment (Public Health Contact<br />

Information) Act 2020 (Cth). 34 This legislation<br />

regulates the collection, storage, use and<br />

disclosure of the personal information<br />

of persons captured by the use of the<br />

application COVIDSafe. The legislation<br />

criminalises the unauthorised collection,<br />

use or disclosure of data obtained via<br />

COVIDSafe. The same legislation provided<br />