Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

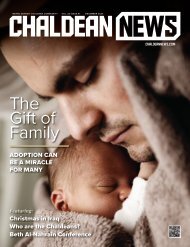

Peter and Samira Essa at Willow Run Airport with family and friends when they arrived to America.<br />

started to actually create printed invitations at this<br />

time in Iraq,” said Fr. Boji. “In the 40s and 50s,<br />

they hosted two important events, the Henna and<br />

the Begana where they took food from the bride’s<br />

house to the groom’s house.”<br />

This happened on the same day, typically a Saturday,<br />

but at different times of the day. “The henna<br />

then was a lot simpler than it is today in America,”<br />

said Fr. Boji. “It was just a few women and the close<br />

relatives with the mother-in-law.”<br />

During this time period some wedding ceremonies<br />

would take place in the early morning hours<br />

around 2 or 3 a.m. “The tradition was that the father<br />

of the bride would not allow his daughter to<br />

leave the house without being married,” said Fr.<br />

Boji. “Usually early morning and it lasted a long<br />

time. Priests recited prayers and blessings.”<br />

After the prayers and blessing, the bride and<br />

groom were taken out and paraded in a circle to<br />

the entire village. The drums and zurna were<br />

played. “As the bride and groom passed, people in<br />

the town, young men, would bring them a bottle of<br />

Arak. “It was a sign of respect,” said Fr. Boji.<br />

Riding a horse was common in the 60s and 70<br />

but not typically ridden by the bride. “They would<br />

put a mattress, the cover sheets and the pillows on<br />

a horse and young boys around 9 or 10 years old<br />

would sit on the mattresses,” said Fr. Boji.<br />

Those invited to the wedding would gather at<br />

the groom’s house for dinner. The next morning,<br />

guests would gather again and bring the envelopes,<br />

the wedding gifts. “They usually cooked Pakota<br />

(Barley dish) for the guests the next day.”<br />

There were traditional celebrations of dancing.<br />

“Usually before the wedding was a couple of days<br />

of gathering and some of the youth of that neighborhood<br />

would dance. But the day of the wedding<br />

itself, whomever wanted to dance could dance but<br />

it was not as big tradition for all weddings.”<br />

In the 50s and 60s, the wedding ceremonies<br />

were moved to 10 or 11 in the morning. “The<br />

groom’s family would go to the bride’s family house<br />

and the youth boys about 15 or 16 years old would<br />

go to the door with a bottle of Arak and a chicken<br />

for mezza later,” said Fr. Boji. “This was like in the<br />

form of payment. They would not let the bride out<br />

of the house until this was paid.”<br />

This is how the tradition became that the<br />

groom’s family paid for the wedding. Later the bottle<br />

of Arak and the chicken were replaced with money.<br />

There was a similar tradition where the groom<br />

would go the bride’s house and young men would<br />

hit the bottom of their shoes with sticks until the<br />

bride’s family gave them Arak and a Chicken.<br />

Although these traditions were left behind in Iraq,<br />

the significant traditions that remain in America are<br />

the prayers. The actual wedding vows today are from<br />

the Latin Rite. The blessing of the bride and groom<br />

and the rings are from Chaldean traditions.<br />

“In 30s and 40s, vows were between the father of<br />

the groom and the father of the bride,” said Fr. Boji.<br />

“The father of groom was proposing and the father<br />

of bride in is accepting. This was part of the ceremony.<br />

In the engagement back then, it was not the<br />

bride and groom, it was groom’s father to the bride’s<br />

father. These traditions are in the liturgical books.”<br />

In Iraq, the groom buys the dresses, “the Chass,”<br />

said Fr. Boji. “The brides’ family would kind of pay<br />

it back with making the food and putting money<br />

in the coat pocket of the groom. The entire town<br />

would see that the bride’s family would pay the<br />

groom back in this way.”<br />

Also in Iraq, the marriages were arranged up<br />

until the 70s and early 80s.<br />

Peter and Samir Essa knew each other for about<br />

three days before they married and didn’t speak to<br />

each other until about three days after the wedding.<br />

“Here is the picture of the two of us on the<br />

day Peter side hi to me and I said hi back,” said<br />

Samira as she pointed to the photo.<br />

That was almost the limit of their conversations<br />

as Peter only spoke English and Samira only<br />

spoke Arabic and Chaldean.<br />

“My mother-in-law would translate for me,”<br />

said Samira, ‘when I first arrived in the United<br />

States. She spoke Sourath. I loved it because I felt<br />

like I was speaking to my own mother.”<br />

During these days of their wedding there was<br />

a revolution in Iraq and King Faisal’s regime was<br />

overthrown. Peter and Samira were unable to leave<br />

Iraq. “My passport was stamped by King Faisal,”<br />

said Samira. “It was no longer valid. I needed a new<br />

stamp by the Prime Minister.”<br />

As an American, Peter was taken by the Em-<br />

THEN AND NOW continued on page 28<br />

<strong>FEBRUARY</strong> <strong>2018</strong> CHALDEAN NEWS 27