Gastroenterology Today Autumn 2023

Gastroenterology Today Autumn 2023

Gastroenterology Today Autumn 2023

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

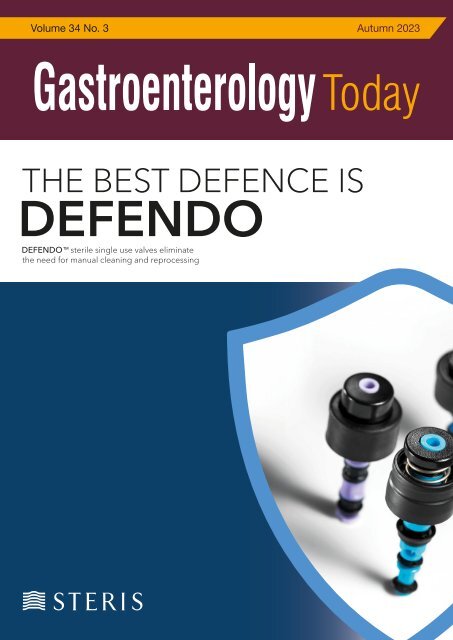

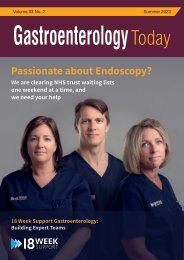

Volume 34 No. 3 <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2023</strong><br />

THE BEST DEFENCE IS<br />

DEFENDO<br />

DEFENDO TM sterile single use valves eliminate<br />

the need for manual cleaning and reprocessing

RReeebmeeeddedddduuuuuuuucccccccaiiiiiiiinnnnnningogggggf yyyytyoooooooouuuuuuuurrerrrrrf wwwwwwwaaaaaaaaiiiiiiiittttttttiiiiiiiinnnnnningogggggf llllklliiiiiiiissssssssttttttttssssssssf aaaaaaaannnnnninddeddddf<br />

iiiiiiiime mmmmmppppppparrerrrrroooooooovvvvvviiiiiiiinnnnnningogggggf pppppppaaaaaaaaattttttttiiiiiiiieeebmeeennnnnninttttttttf eeebmeeexxxpppppppaeeebmeeerrerrrrriiiiiiiieeebmeeennnnnnincccccccaeeebmeee<br />

18f WWeeeeeesleeeeeeslkf Suuuuppppppppppppppoocooooorrrrerrrtttcntttf iiiiiiiisssassssf tttcnttthhhheeeeeeslf UK’ssssssssf llllklleeebmeeeaaaaaaaaddeddddiiiiiiiinnnnnningogggggf iiiiiiiinnnnnninssssssssoooooooouuuuuuuurrerrrrrcccccccaiiiiiiiinnnnnningogggggf<br />

ppppppparrerrrrroooooooovvvvvviiiiiiiiddeddddeeebmeeerrerrrrr..<br />

WWeeeeeeslf sssassssuuuuppppppppppppppoocooooorrrrerrrtttcntttf NHSf ttttttttrrerrrrruuuuuuuussssssssttttttttssssssssf mbyyf ppppppprrrrerrroocooooovviiiiiiiiddddiiiiiiiinnonnnnngggf eeeeeeslxpppppppeeeeeeslrrrrerrriiiiiiiieeeeeeslnnonnnnncca ccceeeeeeslddddf<br />

ccaccplllliiiiiiiinnonnnnniiiiiiiiccaccaaateaaapllllfsssasssstttcntttaaateaaafftttcntttoocooooofrrerrrrreeebmeeeddedddduuuuuuuucccccccaeeebmeeefmbbaaaaaaaacccccccakkkkcllllklloooooooogogggggr,gfiiiiiiiinnnnnnincccccccarrerrrrreeebmeeeaaaaaaaasssssssseeebmeeefcccccccaaaaaaaaapppppppaaaaaaaaacccccccaiiiiiiiittttttttyyyytyy<br />

aaateaaannonnnnnddddf ppppppprrrrerrroocooooovviiiiiiiiddddeeeeeeslf mbb eeebmeeetttttttttttttttteeebmeeerrerrrrrf pppppppaaaaaaaaattttttttiiiiiiiieeebmeeennnnnninttttttttf eeebmeeexxxpppppppaeeebmeeerrerrrrriiiiiiiieeebmeeennnnnnincccccccaeeebmeeef tttcntttrrrrerrreeeeeeslaaateaaatttcntttiiiiiiiinnonnnnngggf<br />

pppppppaaateaaatttcntttiiiiiiiieeeeeeslnnonnnnntttcntttsssassssf iiiiiiiinnonnnnnf tttcnttthhhheeeeeesliiiiiiiirrrrerrrf tttcntttrrrrerrruuuusssasssstttcntttsssassss..<br />

WWhhhhyyf cca ccchhhhoocooooooocooooosssasssseeeeeeslf iiiiiiiinnnnnninssssssssoooooooouuuuuuuurrerrrrrcccccccaiiiiiiiinnnnnningogggggf foooooooorrerrrrrf yyyytyoooooooouuuuuuuurrerrrrrf TTTTrrerrrrruuuuuuuussssssssttttttttr<br />

Meeeeeesleeeeeesltttcntttf yyoocooooouuuurrrrerrrf RRTTTTTTTTf ttttttttaaaaaaaarrerrrrrgogggggeeebmeeettttttttssssssss<br />

Innonnnnncca cccrrrrerrreeeeeeslaaateaaasssasssseeeeeeslf ppppppparrerrrrrooooooooddedddduuuuuuuucccccccattttttttiiiiiiiivvvvvviiiiiiiittttttttyyyyty<br />

Geeeeeesltttcntttf vvvvvvaaaaaaaallllklluuuuuuuueeebmeeef foooooooorrerrrrrf me mmmmmoooooooonnnnnnineeebmeeeyyyyty<br />

WWhhhhyyf woocooooorrrrerrrkf wiiiiiiiitttcnttthhhhf 18f WWeeeeeesleeeeeeslkf Suuuuppppppppppppppoocooooorrrrerrrtttcntttf aaateaaasssassssf aaateaaaf cccccccallllklliiiiiiiinnnnnniniiiiiiiicccccccaaaaaaaaallllkllf<br />

ssssssssttttttttaaaaaaaafff me mmmmmeeebmeeeme mmmmmmbb eeebmeeerrerrrrrr<br />

Eaaateaaarrrrerrrnnonnnnnf eeebmeeexxxttttttttrrerrrrraaaaaaaaf me mmmmmoooooooonnnnnnineeebmeeeyyyyty<br />

Fiiiiiiiinnonnnnnddddf fllllklleeebmeeexxxiiiiiiiimbb llllklleeebmeeef sssssssshhiiiiiiiitfssssssssf aaateaaacca ccccca cccoocooooorrrrerrrddddiiiiiiiinnonnnnngggf tttcntttoocooooof yyoocooooouuuurrrrerrrf sssasssscca ccchhhheeeeeesldddduuuuplllleeeeeesl<br />

TTTTrrerrrrraaaaaaaavvvvvveeebmeeellllkllf aaateaaacca cccrrrrerrroocooooosssasssssssassssf tttcnttthhhheeeeeeslf UK<br />

Foocooooorrrrerrrf mmmoocooooorrrrerrreeeeeeslf iiiiiiiinnonnnnnfoocooooorrrrerrre mmmaaateaaatttcntttiiiiiiiioocooooonnonnnnnf oocooooonnonnnnnf hhhhoocooooowf tttcntttoocoooooy<br />

wwwwwwwoooooooorrerrrrrkkkkcf wwwwwwwiiiiiiiitttttttthhf yyyytyoooooooouuuuuuuurrerrrrrf TTTTrrerrrrruuuuuuuussssssssttttttttr,gf pppppppplllleeeeeeslaaateaaasssasssseeeeeeslf eeeeeesle mmmaaateaaaiiiiiiiipllll<br />

mbb uuuuuuuussssssssddeddddeeebmeeevvvvvv@@1188wwwwwwweeebmeeeeeebmeeekkkkcssssssssuuuuuuuupppppppapppppppaoooooooorrerrrrrtttttttt...cccccccaoooooooome mmmmm<br />

Toocooooof rrrrerrreeeeeeslgggiiiiiiiisssasssstttcnttteeeeeeslrrrrerrrf tttcntttoocooooof wwwwwwwoooooooorrerrrrrkkkkcf wwwwwwwiiiiiiiitttttttthhf uuuuuuuussssssssf aaaaaaaassssssssf aaaaaaaay<br />

cccccccallllklliiiiiiiinnnnnniniiiiiiiicccccccaaaaaaaaallllkllf ssssssssttttttttaaaaaaaafff mmmeeeeeesle mmmmbeeeeeeslrrrrerrrr,gf pppppppplllleeeeeeslaaateaaasssasssseeeeeeslf cca cccoocooooonnonnnnntttcntttaaateaaacca ccctttcnttt<br />

rrerrrrreeebmeeecccccccarrerrrrruuuuuuuuiiiiiiiittttttttme mmmmmeeebmeeennnnnnintttttttt...tttttttteeebmeeeaaaaaaaame mmmmm@@1188wwwwwwweeebmeeeeeebmeeekkkkcssssssssuuuuuuuupppppppapppppppaoooooooorrerrrrrtttttttt...cccccccaoooooooome mmmmm

CONTENTS<br />

CONTENTS<br />

<strong>Gastroenterology</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

4 EDITOR’S COMMENT<br />

08 FEATURE Celiac disease related liver manifestations in<br />

two case study patients<br />

This issue edited by:<br />

Aaron Bhakta<br />

c/o Media Publishing Company<br />

Greenoaks, Lockhill<br />

Upper Sapey, Worcester, WR6 6XR<br />

12 FEATURE Fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel<br />

disease—strongly influenced by depression<br />

and not identifiable through laboratory testing:<br />

a cross-sectional survey study<br />

23 NEWS<br />

27 COMPANY NEWS<br />

ADVERTISING & CIRCULATION:<br />

Media Publishing Company<br />

Greenoaks, Lockhill<br />

Upper Sapey, Worcester, WR6 6XR<br />

Tel: 01886 853715<br />

E: info@mediapublishingcompany.com<br />

www.ambulanceukonline.com<br />

PUBLISHED DATES:<br />

March, June, September and December.<br />

COPYRIGHT:<br />

Media Publishing Company<br />

Greenoaks<br />

Lockhill<br />

Upper Sapey, Worcester, WR6 6XR<br />

COVER STORY<br />

With over 30 steps to sufficient manual cleaning and reprocessing of reusable<br />

Biopsy, Air/Water, and Suction Valves, the DEFENDO range of sterile single use<br />

valves from STERIS UK, eliminates these steps.<br />

PUBLISHERS STATEMENT:<br />

The views and opinions expressed in<br />

this issue are not necessarily those of<br />

the Publisher, the Editors or Media<br />

Publishing Company<br />

Next Issue <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2023</strong><br />

DEFENDO Valves are high-performance, high-quality products that support<br />

procedural control and efficiency. Our verification testing includes multiple tests<br />

for force and suction to help create valves that don’t exhibit some of the common<br />

issues with reusable and other single-use valves: clogging, sticking and loss of<br />

insufflation. When you experience these issues during a procedure, the result<br />

can be a longer, more difficult procedure.<br />

In the range there is the DEFENDO Single Use Y-OPSY Valve, for when the<br />

GI endoscope does not have a dedicated auxiliary water port for irrigation.<br />

This product allows the user to biopsy and irrigate simultaneously through the<br />

working channel.<br />

The newest addition to the DEFENDO range is the DEFENDO Single Use<br />

Cleaning Adapter for OLYMPUS ® endoscopes, used to flush the air/water<br />

channel after the procedure as a first step in the manual cleaning process.<br />

This can help prevent biofilm formation and is seen as one of the most<br />

important steps in cleaning and disinfecting an endoscope.<br />

Available in kits that include, Air/Water, Suction and Biopsy Valves, the DEFENDO<br />

range is compatible with Olympus, Pentax and Fujinon endoscopes. For more<br />

information and/or a free sample please contact your STERIS UK Endoscopy<br />

representative.<br />

Designed in the UK by TGDH<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY – AUTUMN <strong>2023</strong><br />

3

EDITOR’S COMMENT<br />

EDITOR’S COMMENT<br />

Looking beyond the typical.<br />

“Whilst medical<br />

conditions<br />

and diseases<br />

commonly<br />

present with<br />

classical<br />

symptoms<br />

there are also a<br />

host of atypical<br />

presentations<br />

that one must<br />

be aware and<br />

mindful of.”<br />

The differential diagnosis is one of the cornerstones of the medical profession and directs our patient<br />

assessment from the very beginning. From medical students to senior clinicians, it is an everyday part<br />

of clinical practice. Whilst medical conditions and diseases commonly present with classical symptoms,<br />

there are also a host of atypical presentations that one must be aware and mindful of. When the diagnosis<br />

is not forthcoming, we must look beyond the typical.<br />

In this edition of <strong>Gastroenterology</strong> <strong>Today</strong> we present two feature articles. The first highlighting the liver<br />

manifestations of coeliac disease and the importance of exploring the possibility of coeliac disease as<br />

a diagnosis in patients with elevated liver enzymes of unknown aetiology. In the second feature, the authors<br />

encourage clinicians to look beyond disease activity and anaemia in inflammatory bowel disease patients<br />

presenting with fatigue, with the recommendation that these patients should be screened for possible<br />

sub-clinical depression.<br />

Aaron Bhakta<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY – AUTUMN <strong>2023</strong><br />

4

TRIAGE GASTROSCOPY<br />

REFERRALS WITH<br />

GastroPanel® Quick Test<br />

GastroPanel® is a simple and effective noninvasive<br />

test to identify atrophic gastritis<br />

and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) prior to<br />

endoscopy.<br />

Atrophic gastritis – a chronic condition of the gastric<br />

mucosa, is considered to be the greatest independent<br />

risk factor for developing gastric cancer and guidelines<br />

recommend that individuals with extensive gastric<br />

atrophy undergo regular endoscopic surveillance<br />

to closely monitor their disease. Early detection of<br />

individuals with a significant risk of developing gastric<br />

cancer is the key to effective patient management,<br />

helping to reduce unnecessary referrals, and improving<br />

survival rates through earlier diagnoses.<br />

GastroPanel helps select cases for<br />

gastroscopy.<br />

GastroPanel is a simple, effective and low cost blood<br />

test that, through extensive validation, has consistently<br />

proven to be effective in the determination of chronic<br />

atrophic gastritis non-invasively. When GastroPanel<br />

is positive, it helps direct appropriate and effective<br />

treatment plans, including, enhanced image endoscopy,<br />

eradication therapy, and surveillance.<br />

GastroPanel measures three stomach biomarkers<br />

from a finger-prick or venous blood sample, enabling<br />

a thorough and objective investigation of the whole<br />

gastric mucosa, non-invasively, giving clinicians more<br />

confidence in their diagnoses and referrals.<br />

GastroPanel measures concentrations of Pepsinogen I, Pepsinogen II,<br />

Gastrin-17 and H. pylori IgG and produces a comprehensive report.<br />

When endoscopy resources and capacity are<br />

stretched.<br />

This patient-friendly blood test can help transform<br />

the referral pathway for upper GI investigations by<br />

identifying those who need enhanced endoscopy<br />

with biopsies. Implementing GastroPanel could help<br />

to relieve the burden on overstretched endoscopy<br />

services, streamline referrals, and reduce costs.<br />

Scan to find out more or visit www.biohithealthcare.co.uk/gastropanel<br />

BIOHIT HealthCare Ltd<br />

Pioneer House, Pioneer Business Park, North Road,<br />

Ellesmere Port, Cheshire, United Kingdom CH65 1AD<br />

Tel. +44 151 550 4 550<br />

info@biohithealthcare.co.uk<br />

www.biohithealthcare.co.uk

Advertorial feature<br />

What is the ideal treatment strategy for mild to moderate ulcerative<br />

colitis: early treatment escalation or mesalazine optimisation?<br />

Dr Anups de Silva<br />

Consultant Gastroenterologist<br />

and IBD Lead Clinician<br />

Norfolk and Norwich University<br />

Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust<br />

With the advent of novel biologics and small molecules, and the increasing<br />

availability of advanced diagnostic and management tools, the aspirations<br />

for patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) are higher than ever. As such,<br />

the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease<br />

have updated their short- and long-term treatment targets for patients with<br />

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): 1<br />

• Systemic response<br />

• Symptomatic remission and normalisation of C-reactive protein<br />

• Decrease in calprotectin to an acceptable range; normal growth in children<br />

• Endoscopic healing; normalised quality of life and absence of disability<br />

However, the role and timing of treatment escalation to achieve these goals is a<br />

key area of debate. 2 Should we utilise these newer therapies as soon as patients<br />

are eligible for them, or should we ensure that first-line established therapies,<br />

such as mesalazine, have been fully optimised before treatment escalation?<br />

Treatment strategies should be tailored to patients’<br />

disease course<br />

Whilst treatment must be tailored to the severity of patients’ disease, it is likely<br />

to change over time. 2–4<br />

A 20-year, prospective, population-based study found that 69% of patients<br />

(n=340) had a disease course characterised by initially highly-active disease<br />

followed by long-term remission or instances of mild intestinal symptoms. 4<br />

Therefore, many patients may achieve good outcomes without the need for<br />

early intervention with biologics. 4<br />

The most common long-term disease course in patients with UC 4<br />

Initially highly-active disease<br />

followed by remission or mild 69%<br />

intestinal symptoms<br />

0 years 20 years<br />

Adapted from Monstad et al. 2021. 4<br />

Early anti-TNF use does not reduce hospitalisation and<br />

surgery rates<br />

In a retrospective study in patients with UC (n=318), early anti-tumour necrosis<br />

factor (TNF) use (≤2 years after diagnosis) had no effect on hospitalisation and<br />

surgery rates compared with anti-TNF use >2 years after diagnosis. 5<br />

Disease activity<br />

In addition to the lack of evidence supporting general early anti-TNF use in UC,<br />

several challenges must also be considered when determining the optimal<br />

treatment strategy:<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

A Cochrane review examining the adverse effects of biologics concluded<br />

that they were associated with statistically significantly higher rates of<br />

serious infection, tuberculosis reactivation, total adverse events (AEs) and<br />

withdrawal due to AEs compared with control treatment. 6 A separate<br />

Cochrane review into the use of mesalazine for the maintenance of<br />

remission of UC found little or no difference between mesalazine and<br />

placebo in commonly reported AEs. These included flatulence, abdominal<br />

pain, nausea, diarrhoea, headache and dyspepsia 7<br />

Early use may limit the effectiveness of treatment, as previous anti-TNF<br />

use is associated with a heightened probability of treatment failure and loss<br />

of response with subsequent anti-TNF therapy 8<br />

Anti-TNF therapies are vastly more expensive than standard first-line<br />

treatments such as mesalazine. 9 Even in the age of biosimilars, a single<br />

dose of an anti-TNF can cost more than a whole year’s treatment<br />

with mesalazine 9<br />

Mesalazine optimisation remains the recommended<br />

treatment strategy<br />

The British Society of <strong>Gastroenterology</strong> recommend optimising the use of<br />

first-line mesalazine treatment in patients with mild to moderate UC before<br />

escalating to other therapies by: 3<br />

• Increasing the dose up to 4–4.8g/day for the induction of remission<br />

• Combining oral and rectal mesalazine (sometimes referred to as ‘top and tail<br />

treatment’) for patients with an incomplete response<br />

• Tailoring the choice of formulation to take into account patients’ preferences,<br />

likely adherence and cost<br />

These strategies can have a profound effect on the outcomes that can be<br />

achieved with mesalazine. 10–13<br />

Dr de Silva’s case study: mesalazine dose optimisation to<br />

control a flare<br />

Patient characteristics:<br />

• 37-year-old male<br />

• 2-year history of left-sided UC<br />

• Treated with Octasa ® 2.4g/day taken once-daily<br />

Presenting complaint:<br />

• For 3 weeks he had been experiencing an increased frequency of<br />

looser-consistency bowel movements (4 times per day and once at night)<br />

with increased urgency, tenesmus and blood on most occasions<br />

• Admitted to periods of non-compliance due to a heavy work schedule and<br />

personal stresses<br />

Investigations:<br />

• Stool samples were sent for analysis with enteric pathogen polymerase chain<br />

reaction (PCR) and Clostridioides difficile assay. Both were negative<br />

• Faecal calprotectin was 1,424µg/g<br />

• A flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed a Mayo Clinic Score of 2 and colitis<br />

extending to the descending colon, with solid stool beyond this<br />

Solution:<br />

• His treatment was optimised by:<br />

– Increasing the dose of Octasa ® to 4.8g/day, taken in 2 divided doses<br />

– Starting treatment with a 1g mesalazine liquid enema at night, along with<br />

an Octasa ® 1g suppository 12 hours apart from the enema<br />

• During reassessment 10 days later, his bowel movement frequency had<br />

reverted back to his normal habit of twice daily with a more solid stool

Mesalazine optimisation can increase response rates vs<br />

standard dosing<br />

In a randomised, multicentre induction trial with an open-label extension,<br />

patients with moderately active UC and moderate/severe mucosal inflammation<br />

initially received Octasa ® 3.2g/day for 8 weeks (n=817). 10 At week 8, patients<br />

had their doses adjusted depending on their response to treatment, with those<br />

who did not respond having their dose increased to 4.8g/day. 10<br />

Response rate after increasing the dose of Octasa ® in patients with<br />

moderate UC who did not respond to initial treamtent 10<br />

Non-responders to<br />

Octasa ® 3.2g/day at<br />

week 8 (n=243)<br />

Adapted from D’Haens et al. 2017. 10<br />

Dose increase to<br />

4.8g/day for<br />

8 weeks (n=243)<br />

75.3% achieved a response<br />

with Octasa ® optimisation<br />

(n=183/243)<br />

Mesalazine optimisation can allow more patients to achieve<br />

mucosal healing vs standard dosing<br />

A post-hoc analysis of two prospective 6-week, double-blind, randomised studies<br />

compared mucosal healing rates (defined as a Mayo endoscopy subscore of 0 or 1)<br />

in patients with moderate UC who received 2.4g/day vs 4.8g/day oral mesalazine. 11<br />

Of those patients treated with 4.8g/day, 80% achieved mucosal healing vs only<br />

68% treated with 2.4g/day (n=322; p=0.012). Furthermore, mucosal healing<br />

was found to be well correlated with clinical response and improvement in<br />

patient-reported quality of life. 11<br />

Mesalazine optimisation can reduce treatment costs vs<br />

standard treatment<br />

Modelled data from meta-analyses were used to compare mesalazine dose<br />

optimisation (using the maximum dose, and combined oral and rectal therapy<br />

before treatment escalation) with standard treatment in 10,000 patients with<br />

mild to moderate UC. 12 It found mesalazine dose optimisation:<br />

• Increased the initial remission rate from 47% to 66%<br />

(n=4,725 vs n=6,565) 12<br />

• Potentially avoided AEs associated with other<br />

treatment classes, including psychological,<br />

gastrointestinal, dermatological and haematological<br />

AEs, infections and injection/infusion-related<br />

reactions 12<br />

Despite greater initial acquisition costs of increased mesalazine doses, the<br />

substantial improvements in patient outcomes associated with mesalazine dose<br />

optimisation resulted in net annual savings of £272 per patient. 12 With over<br />

200,000 people living with mild to moderate UC in the UK, it has the potential<br />

to save the NHS over £54 million per year. 12,14,15<br />

Mesalazine optimisation can help meet patient preferences<br />

Up to 3 in 5 patients have been found to be non-adherent to mesalazine in<br />

observational studies. 16–19 However, prescribing mesalazines according to<br />

patients’ preferences may help to improve this and reduce their risk of<br />

relapse. 13,19 Patients should be prescribed a mesalazine that gives them the<br />

number of tablets per administration, number of administrations per day and<br />

treatment appearance that they prefer. 13<br />

Mesalazine optimisation is the clear choice for mild to<br />

moderate UC<br />

Mesalazine optimisation should be employed before early treatment escalation<br />

due to the available evidence:<br />

• The majority of patients’ disease courses do not warrant early anti-TNF use 4,5<br />

• Early anti-TNF use can pose several challenges, including reduced<br />

effectiveness when anti-TNFs are used subsequently and high costs 8,9<br />

• Mesalazine optimisation can increase rates of response and mucosal<br />

healing, meet patients’ preferences and limit treatment costs vs standard<br />

dosing and treatment 10–13<br />

References: 1. Turner D et al. <strong>Gastroenterology</strong> 2021; 160(5): 1570–1583. 2. Raine T et al. J Crohns Colitis 2022; 16(1): 2–17. 3. Lamb CA<br />

et al. Gut 2019; 68(Suppl 3): s1–s106. 4. Monstad IL et al. J Crohns Colitis 2021; 15(6): 969–979. 5. Targownik LE et al. Clin Gastroenterol<br />

Hepatol 2022; 20(11): 2607–2618.e14. 6. Singh JA et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 2: CD008794. 7. Murray A et al. Cochrane<br />

Database Syst Rev 2020; 8: CD000544. 8. Atreya R et al. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020; 7: 517. 9. BNF. Accessed online, August <strong>2023</strong>.<br />

10. D’Haens GR et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 46(3): 292–302. 11. Lichtenstein GR et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 33(6):<br />

672–678. 12. Louis E et al. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2022; 9(1): e000853. 13. MacKenzie-Smith L et al. Inflamm Intest Dis 2018; 3(1):<br />

43–51. 14. Crohn’s and Colitis UK. Epidemiology Summary: Incidence and Prevalence of IBD in the United Kingdom. Available at: https://<br />

crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/media/4e5ccomz/epidemiology-summary-final.pdf [accessed August <strong>2023</strong>]. 15. Schreiber S et al. J Crohns Colitis<br />

2013; 7(6): 497–509. 16. Testa A et al. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017; 11: 297–303. 17. Kane SV et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96(10):<br />

2929–2933. 18. Shale MJ et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003; 18(2): 191–198. 19. Kane SV et al. Am J Med 2003; 114(1): 39–43.<br />

OCTASA 1g Suppositories (mesalazine) - Prescribing Information<br />

Presentation: Suppository containing 1g mesalazine. Indications: Treatment of acute mild to moderate ulcerative proctitis. Maintenance of<br />

remission of ulcerative proctitis Dosage and administration: Adults and older people: Acute treatment - one Octasa 1 g Suppository once<br />

daily (equivalent to 1 g mesalazine daily) inserted into the rectum. Maintenance treatment - one Octasa 1 g Suppository once daily (equivalent<br />

to 1 g mesalazine daily) inserted into the rectum. Children: Limited experience and data for use in children. Method of administration: for<br />

rectal use, preferably at bedtime. Duration of use to be determined by the physician. Contra-indications: Hypersensitivity to salicylates<br />

or any of the excipients, severe impairment of hepatic or renal function. Warnings and Precautions: Blood tests and urinary status (dip<br />

sticks) should be determined prior to and during treatment, at discretion of treating physician. Caution in patients with impaired hepatic<br />

function. Do not use in patients with impaired renal function. Consider renal toxicity if renal function deteriorates during treatment. Cases<br />

of nephrolithiasis have been reported with mesalazine treatment. Ensure adequate fluid intake during treatment. Monitor patients with<br />

pulmonary disease, in particular asthma, very carefully. Patients with a history of adverse drug reactions to sulphasalazine should be kept<br />

under close medical surveillance on commencement of therapy, discontinue immediately if acute intolerance reactions occur (e.g. abdominal<br />

cramps, acute abdominal pain, fever, severe headache and rash). Severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARS), including Drug reaction with<br />

eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) have been reported.<br />

Stop treatment immediately if signs and symptoms of severe skin reactions are seen. Mesalazine may produce red-brown urine discoloration<br />

after contact with sodium hypochlorite bleach (e.g. in toilets cleaned with sodium hypochlorite contained in certain bleaches). Interactions:<br />

No interaction studies have been performed. May increase the myelosuppressive effects of azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine or thioguanine.<br />

May decrease the anticoagulant activity of warfarin. Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: Only to be used during pregnancy and lactation<br />

when the potential benefit outweighs the possible risk. No effects on fertility have been observed. Adverse reactions: Rare: Headache,<br />

dizziness, myocarditis, pericarditis, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, flatulence, nausea, vomiting, constipation, photosensitivity, Very rare: Altered<br />

blood counts (aplastic anaemia, agranulocytosis, pancytopenia, neutropenia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia), peripheral neuropathy, allergic<br />

and fibrotic lung reactions (including dyspnoea, cough, bronchospasm, alveolitis, pulmonary eosinophilia, lung infiltration, pneumonitis),<br />

acute pancreatitis, impairment of renal function including acute and chronic interstitial nephritis and renal insufficiency, alopecia, myalgia,<br />

arthraligia, hypersensitivity reactions (such as allergic exanthema, drug fever, lupus erythematosus syndrome, pancolitis), changes in liver<br />

function parameters (increase in transaminases and parameters of cholestasis), hepatitis, cholestatic hepatitis, oligospermia (reversible). Not<br />

known: Nephrolithiasis, Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.<br />

Consult the Summary of Product Characteristics in relation to other adverse reactions. Marketing Authorisation Numbers, Package<br />

Quantities and basic NHS price: PL36633/0011; packs of 10 suppositories (£9.87) and 30 suppositories (£29.62). Legal category:<br />

POM. Marketing Authorisation Holder: Tillotts Pharma UK Ltd, The Larbourne Suite, The Stables, Wellingore Hall, Wellingore, Lincolnshire,<br />

LN5 0HX, UK. Octasa is a trademark. © 2021 Tillotts Pharma UK Ltd. Further Information is available from the Marketing Authorisation Holder.<br />

Date of preparation of PI: November 2022<br />

Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk.<br />

Adverse events should also be reported to Tillotts Pharma UK Ltd. (address as above) Tel: 01522 813500.<br />

OCTASA 400mg, 800mg & 1600mg Modified Release Tablets (mesalazine) - Prescribing Information<br />

Presentation: Modified Release tablets containing 400mg, 800mg or 1600mg mesalazine. Indications: All strengths: Ulcerative Colitis -<br />

Treatment of mild to moderate acute exacerbations. Maintenance of remission. 400mg & 800mg only: Crohn’s ileocolitis - Maintenance of<br />

remission. Dosage and administration: 400mg & 800mg tablets – Adults: Mild acute disease: 2.4g once daily or in divided doses, with<br />

concomitant steroid therapy where indicated. Moderate acute disease: 2.4g – 4.8g daily. 2.4g may be taken once daily or in divided doses,<br />

higher doses should be taken in divided doses. Maintenance therapy: 1.2g – 2.4g once daily or in divided doses. 1600mg tablets – Adults:<br />

Acute exacerbations: up to 4.8g, once daily or in divided doses. Maintenance: 1600mg daily. Tablets must be swallowed whole. Elderly:<br />

400mg & 800mg - normal adult dose may be used unless liver or renal function is severely impaired. 1600mg - no studies in elderly patients<br />

have been conducted. Children: 400mg & 800mg - limited documentation of efficacy in children >6 years old. Dose to be determined<br />

individually. Generally recommended that half the adult dose may be given to children up to a body weight of 40 kg; and the normal adult<br />

dose to those above 40 kg. 1600mg – safety and efficacy not established in children. Contra-indications: Hypersensitivity to salicylates,<br />

mesalazine or any of the excipients, severe impairment of hepatic or renal function (GFR less than 30 ml/min/1.73m 2 ). Warnings and<br />

Precautions: Urinary status (dip sticks) should be determined prior to and during treatment, at discretion of treating physician. Caution<br />

in patients with raised serum creatinine or proteinuria. Stop treatment immediately if renal impairment is evident. Cases of nephrolithiasis<br />

have been reported with mesalazine treatment. Ensure adequate fluid intake during treatment. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions<br />

(SCARS), including Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal<br />

necrolysis (TENS) have been reported. Stop treatment immediately if signs and symptoms of severe skin reactions are seen. Haematological<br />

investigations are recommended prior to and during treatment, at discretion of treating physician. Stop treatment immediately if blood<br />

dyscrasias are suspected or evident. Caution in patients with impaired hepatic function. Liver function should be determined prior to and<br />

during treatment, at the discretion of the treating physician. Do not use in patients with previous mesalazine-induced cardiac hypersensitivity<br />

and use caution in patients with previous myo- or pericarditis of allergic background. Monitor patients with pulmonary disease, in particular<br />

asthma, very carefully. In patients with a history of adverse drug reactions to sulphasalazine, discontinue immediately if acute intolerance<br />

reactions occur (e.g. abdominal cramps, acute abdominal pain, fever, severe headache and rash). Use with caution in patients with gastric<br />

or duodenal ulcers. Intact 400mg & 800mg tablets in the stool may be largely empty shells. If this occurs repeatedly patients should consult<br />

their physician. Use with caution in the elderly, subject to patients having normal or non-severely impaired renal and liver function. Patients<br />

with rare hereditary problems of galactose intolerance, the Lapp lactase deficiency or glucose-galactose malabsorption, should not take<br />

the 400mg or 800mg tablets. Mesalazine may produce red-brown urine discoloration after contact with sodium hypochlorite bleach (e.g.<br />

in toilets cleaned with sodium hypochlorite contained in certain bleaches). Interactions: No interaction studies have been performed.<br />

May decrease the anticoagulant activity of warfarin. Caution when used with known nephrotoxic agents such as NSAIDs, methotrexate<br />

and azathioprine. May increase the myelosuppressive effects of azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine or thioguanine. Monitoring of blood cell<br />

counts is recommended if these are used concomitantly. Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: Only to be used during pregnancy and<br />

lactation when the potential benefit outweighs the possible risk. No effects on fertility have been observed. Adverse reactions: Common:<br />

dyspepsia, rash. Uncommon: eosinophilia (as part of an allergic reaction), paraesthesia, urticaria, pruritus, pyrexia, chest pain. Rare:<br />

headache, dizziness, myocarditis, pericarditis, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, flatulence, nausea, vomiting, photosensitivity. Very rare: altered<br />

blood counts (aplastic anemia, agranulocytosis, pancytopenia, neutropenia, leucopenia, thrombocytopenia), blood dyscrasia, hypersensitivity<br />

reactions (such as allergic exanthema, drug fever, lupus erythematosus syndrome, pancolitis), peripheral neuropathy, allergic and fibrotic lung<br />

reactions (including dyspnoea, cough, bronchospasm, alveolitis, pulmonary eosinophilia, lung infiltration, pneumonitis), interstitial pneumonia,<br />

eosinophilic pneumonia, lung disorder, acute pancreatitis, changes in liver function parameters (increase in transaminases and cholestasis<br />

parameters), hepatitis, cholestatic hepatitis, alopecia, myalgia, arthralgia, impairment of renal function including acute and chronic interstitial<br />

nephritis and renal insufficiency, renal failure which may be reversible on withdrawal, nephrotic syndrome, oligospermia (reversible). Not<br />

known: Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, pleurisy, lupuslike<br />

syndrome with pericarditis and pleuropericarditis as prominent symptoms as well as rash and arthralgia, nephrolithiasis, intolerance<br />

to mesalazine with C-reactive protein increased and/or exacerbation of symptoms of underlying disease, blood creatinine increased,<br />

weight decreased, creatinine clearance decreased, amylase increased, red blood cell sedimentation rate increased, lipase increased, BUN<br />

increased. Consult the Summary of Product Characteristics in relation to other adverse reactions. Marketing Authorisation Numbers,<br />

Package Quantities and basic NHS price: 400mg - PL36633/0002; packs of 90 tablets (£19.50) and 120 tablets (£26.00). 800mg -<br />

PL36633/0001; packs of 90 tablets (£40.38) and 180 tablets (£80.75). 1600mg – PL36633/0009; packs of 30 tablets (£30.08). Legal<br />

category: POM. Marketing Authorisation Holder: Tillotts Pharma UK Ltd, The Larbourne Suite, The Stables, Wellingore Hall, Wellingore,<br />

Lincolnshire, LN5 0HX, UK. Octasa is a trademark. © 2022 Tillotts Pharma UK Ltd. Further Information is available from the Marketing<br />

Authorisation Holder. Date of preparation of PI: November 2022<br />

Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk.<br />

Adverse events should also be reported to Tillotts Pharma UK Ltd. (address as above) Tel: 01522 813500.<br />

This advertorial has been funded and initiated by Tillotts Pharma UK (TPUK). The content in this<br />

advertorial has been driven by Dr de Silva and written by TPUK. Dr de Silva has reviewed the<br />

content, and TPUK have ensured technical accuracy and compliance with appropriate regulations<br />

and legislation.<br />

Date of preparation: August <strong>2023</strong>. PU-01292.

FEATURE<br />

CELIAC DISEASE RELATED LIVER<br />

MANIFESTATIONS IN TWO CASE<br />

STUDY PATIENTS<br />

RESEARCH<br />

Key words: celiac, gluten free, dietitian, liver, elevated liver enzymes<br />

Kathleen Eustace, MPH, RDN, LD, CNSC Corresponding Author<br />

UT Southwestern Medical Center Department of Clinical Nutrition<br />

Associate professor<br />

6011 Harry Hines Blvd. Dallas, TX 75390-8877<br />

214-648-1520<br />

kathleen.eustace@utsouthwestern.edu<br />

Alicia Gilmore, MS, RD, CSO, LD<br />

UT Southwestern Medical Center Department of Clinical Nutrition<br />

Associate professor<br />

6011 Harry Hines Blvd. Dallas, TX 75390-8877<br />

214-648-1520<br />

alicia.gilmore@utsouthwestern.edu<br />

Funding/ Support Disclosure: No funding was received for this article.<br />

Conflict of Interest: Neither author has any conflict of interests to report.<br />

Abstract<br />

from exposure of dietary gluten. CD primarily affects the small intestine<br />

and resolves with a gluten free diet (1). Classic presentation includes<br />

diarrhea, gassiness, abdominal pain, iron deficiency anemia, and weight<br />

loss. Organs, connective tissues, skin, joints, and the nervous system<br />

can also be affected by the systemic inflammatory response to gluten<br />

(2). Non-gastrointestinal manifestations include joint pain, dermatitis<br />

herpetiformis, low bone mineral density, and liver disease which<br />

manifests initially as elevated alanine and aspartate aminotransferase<br />

(ALT and AST, respectively) (1, 3). Diagnostic evaluation of CD should be<br />

completed with any range of symptoms without an alternative etiology,<br />

not just with presentation of historically associated symptoms.<br />

Elevated transaminase levels, or liver function tests (LFTs), can be<br />

a primary, and often overlooked, symptom of CD in the absence of<br />

additional symptoms (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Elevated LFT levels are reported<br />

in 40% of adults and 60% of children with CD (8). Undiagnosed celiac<br />

disease accounts for 9% of patients with transaminase elevations of<br />

unknown etiology (9, 10). The cause of CD related liver involvement<br />

is unclear, but literature suggests a possible mechanism is increased<br />

intestinal permeability of CD, allowing toxins and inflammatory mediators<br />

to reach the liver via the lymphatic system (11). Dietary therapy will<br />

reverse CD related liver disease, potentially preventing progression to<br />

overt liver failure (3, 11).<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY – AUTUMN <strong>2023</strong><br />

Celiac sprue or Celiac disease (CD) is an autoimmune disease that<br />

resolves with the removal of gluten from the diet. Traditionally CD<br />

presents with weight loss, iron deficiency anemia, and gastrointestinal<br />

symptoms such as gas, pain, and/or bloating. However, there is an<br />

increasing prevalence of novel presentations of CD, such as dermatitis<br />

herpetiformis, joint pain, and elevated transaminase levels. Elevated<br />

transaminase levels are cited in literature as the only presentation of<br />

celiac disease. Progression to liver disease and even liver failure can<br />

occur if not addressed in early stages with the initiation of a gluten<br />

free diet. Physician awareness of CD related liver involvement is of the<br />

upmost importance for both diagnosis and dietary nonadherence.<br />

Registered Dietitian Nutritionists (RDN) specializing in gluten free diets<br />

are poised to provide in-depth diet initiation and adherence support.<br />

RDNs can also perform the important task of educating on long term<br />

adherence to prevent poor outcomes including liver disease. This case<br />

study reviews two patients presenting with CD related transaminase<br />

elevations without other clinical manifestations. The purpose of this<br />

review is to highlight the importance of recognizing CD as an etiology<br />

for elevated transaminase levels and the valuable role the RDN plays<br />

in supporting dietary treatment to prevent and treat CD related liver<br />

disease.<br />

Background<br />

Celiac sprue or Celiac disease (CD) is an autoimmune disorder resulting<br />

Strict adherence to the prescribed gluten free diet is paramount to the<br />

prevention of CD related liver disease. Nonadherence occurs in 25-<br />

40% of CD patients due to intentional and unintentional consumption<br />

of gluten resulting in persistence and/or recurrence of symptoms (12,<br />

13). Amelioration of symptoms that interfere with daily life supports<br />

compliance with the required diet. However, if symptoms are silent, they<br />

can be ignored by patients inclined to noncompliance with the gluten<br />

free diet. CD related LFT abnormalities without other conspicuous<br />

symptoms will often go unnoticed by the patient (3, 14, 15). Registered<br />

dietitian nutritionist (RDN) educating on prescribed dietary therapy<br />

will need to emphasize the risk of symptom occurrence with dietary<br />

noncompliance at initial and follow up visits. In this article, we report<br />

two cases of CD presenting solely with elevated LFTs. The first where<br />

the diagnosis was incidental to elevated levels, while the second<br />

demonstrates dietary non-compliance resulting in liver disease in the<br />

absence of other symptoms. All HIPAA (Health Information Patient<br />

Accountability Act) guidelines and privacy rules were followed with<br />

respect to using or accessing PHI in the review of the cases.<br />

Case Study 1<br />

A 30-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to the <strong>Gastroenterology</strong><br />

Clinic for elevated transaminase levels found incidentally during a<br />

pre-operative evaluation. Past medical history included thyroid cancer<br />

with full thyroidectomy, type I diabetes, asthma, and childhood anemia.<br />

8

FEATURE<br />

A liver ultrasound was normal including size, texture, and echogenicity.<br />

Immunoglobulin G and Immunoglobulin A antibodies were assessed<br />

with both levels within the normal range. The patient denied weight<br />

loss or gastrointestinal symptoms including diarrhea, gas, or post<br />

prandial abdominal pain. Etiologies of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease<br />

and hepatic glycogenosis (due to the patient’s diagnosis of type 1<br />

Diabetes Mellitus) were suspected. The patient was referred for an<br />

esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy. EGD was notable<br />

for erythematous mucosa in the antrum as well as flattened mucosa<br />

in the duodenum. Biopsies confirmed the diagnosis along with an<br />

elevated serum tissue transglutaminase. The patient received the CD<br />

diagnosis and a referral to an RDN. The completed nutrition assessment<br />

included both anthropometrics and 24-hour diet recall. There had been<br />

no change in weight prior to the visit or with the diagnosis of CD. Blood<br />

glucose concentrations were stable, with the patient using a Medtronic<br />

pump and Dexcom monitor. Transaminase levels are noted in Table 1.<br />

The patient admitted difficulty identifying hidden sources of gluten, as<br />

well as concerns for both eating out safely and the potential for nutrient<br />

deficiencies (iron, b vitamins). Formal gluten free diet education was<br />

provided and individualized to the patients’ need. Supplementation of<br />

a gluten free multivitamin and mineral supplement was recommended.<br />

Lifelong dietary adherence was emphasized with the patient as a<br />

requirement for long term positive outcomes. Dietary compliance with a<br />

gluten free diet was measured by normalization of LFTs and a reduction<br />

in tissue transglutaminase level at 5 months and 11 months respectively<br />

after initial diagnosis.<br />

Subsequent scheduled follow ups were cancelled by the patient,<br />

and she was lost to follow up.<br />

Case Study 2<br />

A 49-year-old Caucasian female with a history of CD presented for<br />

dietary re-education due to long-term gluten free diet non-adherence.<br />

The patient presented nine years prior with abdominal pain and irregular<br />

stool output including diarrhea and constipation. Serologies from an<br />

outside facility were consistent with a diagnosis of CD and an EGD with<br />

small bowel biopsy supported the diagnosis of CD. The patient received<br />

formal education on a gluten free diet at initial diagnosis. The patient<br />

reported good dietary adherence initially but gradually reintroduced<br />

gluten without recurrence of symptoms. Mildly elevated transaminase<br />

levels were noted four years after diagnosis but normalized until eight<br />

years after diagnoses (Table 2). No alternative etiology for her elevated<br />

LFTs was determined leading to the conclusion that her underlying<br />

CD and subsequent dietary noncompliance was the cause of her<br />

transaminase elevations. Subsequent serology revealed an elevated<br />

serum tissue transglutaminase. The patient reinitiated a gluten free diet<br />

and a formal RDN referral was placed. A nutrition assessment revealed<br />

normal weight status, supplementation of iron, calcium, and vitamin<br />

D, as well as recent initiation of gluten free diet. A diet recall revealed<br />

gluten ingestion via flour-based cake, bread, and foods with a high risk<br />

of cross contamination including specialty coffees, hot cereals, and<br />

foods cooked with unknown seasonings. Individualized formal education<br />

was provided to reinforce adherence to a gluten free diet. The RDN<br />

emphasized strict diet adherence to prevent further complications.<br />

Liver transaminase levels returned to normal limits six weeks after<br />

reinitiating a strict gluten free diet (Table 2). Follow up with the RDN<br />

was scheduled on an as needed basis.<br />

Discussion<br />

Fifteen to fifty-five percent of CD patients experience elevated<br />

transaminase levels and/or changes in liver morphology (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6,<br />

7, 8, 9, 10). Non-adherence to a gluten free diet can lead to progressive<br />

liver disease and advancement to cirrhosis and liver failure in some<br />

individuals (3). Adherence to a gluten free diet is critical to prevent CD<br />

related liver disease progression. Both physicians and RDNs should<br />

recognize nonstandard presentations of CD. Case 1 highlights the<br />

importance of recognizing and diagnosing CD in the setting of isolated<br />

transaminase elevations. An inclusive work up with a liver panel and tissue<br />

Table 1 Liver Chemistry Results Before and After Diagnosis of Celiac Disease<br />

Baseline 2 months 5 months 9 months 11 months<br />

Alk Phos (U/mL) 109 116 117 92<br />

Alpha 1 Antitrypsin 200<br />

ALT (U/mL) 59 56 29 23<br />

AST (U/mL) 38 37 20 22<br />

Tissue transglutaminase AB, IGA, S (U/mL) ≥100.0 7<br />

Table 2 Liver Chemistry Results After Diagnosis of Celiac Disease for Case 2<br />

Post 4 years Post 7 years Post 8 years a<br />

January April July October December<br />

AST (U/L) 60 29 61 53 45 38 22<br />

ALT (U/L) 68 24 41 37 52 52 29<br />

TTG (U/mL) 15.9<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY – AUTUMN <strong>2023</strong><br />

a<br />

Labs were drawn throughout the year due to the initial findings of hypertransaminemia<br />

9

FEATURE<br />

transglutaminase collected prior to diagnosis should be repeated after<br />

6-12 months of strict adherence to a gluten free diet (5). These tests act as<br />

an indicator of dietary adherence and disease activity. As with the patient<br />

in Case 1, transaminase levels are expected to return to normal on a strict<br />

gluten free diet.<br />

Case 2 highlights how CD patients non-compliant with dietary restrictions<br />

can expect morphological and/or systemic changes. Elevated liver<br />

transaminase levels were not part of her initial presentation, but an<br />

unexpected consequence of gluten reintroduction. Gradual introduction<br />

of gluten overtime without overt symptoms recurrence led to increased<br />

dietary noncompliance, as reported by the patient. Dietary education<br />

must emphasize adherence even after initial symptom resolution due to<br />

the underlying pathological changes that can occur with gluten ingestion<br />

in patients with CD. Physicians and RDNs should reinforce the importance<br />

of dietary adherence to prevent long term consequences of untreated<br />

CD. Emphasis should be placed on the risk associated with dietary nonadherence<br />

even in the absence of obvious clinical symptoms such as<br />

elevated plasma transaminase levels.<br />

Restrictive diets such as the gluten free diet can present a challenge.<br />

Education and reinforcement of a strict gluten free diet by an RDN can<br />

prevent poor dietary adherence (16). The Nutrition Care Manual ® , a<br />

nutrition intervention guide provided by the Academy of Nutrition and<br />

Dietetics. recommends ‘if the potential exists for a nutrition diagnosis<br />

to develop (i.e., dietary nonadherence), the registered dietitian should<br />

establish an appropriate method and interval for follow up (17). This<br />

guideline is designed to reinforce dietary adherence to prevent CD<br />

manifestations of severe negative consequence including not only the<br />

reviewed CD-related hepatic pathology reviewed here, but others such as<br />

an increased risk of certain cancers (1, 7). Unfortunately, neither patient<br />

was seen for follow up after initial diagnosis and consultation. Case 2 had<br />

no follow up with an RDN over the 8 years from initial CD diagnosis until<br />

liver complications developed. Likewise, case 1 failed to schedule a follow<br />

up consultation. Physician appointments with CD patients should include<br />

screening for dietary adherence with subsequent referral to RDNs as<br />

needed to reinforce adherence to a strict gluten free diet.<br />

gluten-free diet may reverse hepatic failure. <strong>Gastroenterology</strong>.<br />

2002;122(4):881-8.<br />

4. Korpimaki S, Kaukinen K, Collin P, Haapala AM, Holm P, Laurila K,<br />

et al. Gluten-Sensitive Hypertransaminasemia in Celiac Disease:<br />

An Infrequent and Often Subclinical Finding. American Journal of<br />

<strong>Gastroenterology</strong>. 2011;106(9):1689-96.<br />

5. Kamath PS. Clinical approach to the patient with abnormal liver<br />

test results. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71(11):1089-94; quiz 94-5.<br />

6. Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. The liver in celiac disease. Hepatology.<br />

2007;46(5):1650-8.<br />

7. Sainsbury A, Sanders DS, Ford AC. Meta-analysis: Coeliac<br />

disease and hypertransaminasaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.<br />

2011;34(1):33-40.<br />

8. Rubio-Tapia A, Abdulkarim AS, Wiesner RH, Moore SB,<br />

Krause PK, Murray JA. Celiac disease autoantibodies in severe<br />

autoimmune liver disease and the effect of liver transplantation.<br />

Liver Int. 2008;28(4):467-76.<br />

9. Volta U, De Franceschi L, Lari F, Molinaro N, Zoli M, Bianchi FB.<br />

Coeliac disease hidden by cryptogenic hypertransaminasaemia.<br />

Lancet. 1998;352(9121):26-9.<br />

10. Bardella MT, Vecchi M, Conte D, Del Ninno E, Fraquelli M,<br />

Pacchetti S, et al. Chronic unexplained hypertransaminasemia may<br />

be caused by occult celiac disease. Hepatology. 1999;29(3):654-<br />

7.<br />

11. Villavicencio Kim J, Wu GY. Celiac Disease and Elevated Liver<br />

Enzymes: A Review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2021;9(1):116-24.<br />

12. Gladys K, Dardzinska J, Guzek M, Adrych K, Malgorzewicz<br />

S. Celiac Dietary Adherence Test and Standardized Dietician<br />

Evaluation in Assessment of Adherence to a Gluten-Free Diet in<br />

Patients with Celiac Disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(8).<br />

13. Hall NJ, Rubin GP, Charnock A. Intentional and inadvertent nonadherence<br />

in adult coeliac disease. A cross-sectional survey.<br />

Appetite. 2013;68:56-62.<br />

14. Hagander B, Berg NO, Brandt L, Norden A, Sjolund K,<br />

Stenstam M. Hepatic injury in adult coeliac disease. Lancet.<br />

1977;2(8032):270-2.<br />

15. Ludvigsson JF, Elfstrom P, Broome U, Ekbom A, Montgomery<br />

SM. Celiac disease and risk of liver disease: a general populationbased<br />

study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(1):63- 9 e1.<br />

16. Nealis C LC, Hollenbeck C. The Recovery Experience of Celiac<br />

Patients Following a Gluten-Free Diet: An ExploratoryStudy.<br />

Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2016;116;<br />

9:A96.<br />

17. Dietetics AoNa. Celiac Disease. Nutrition Therapy Efficacy 2021<br />

[Available from: https://www.nutritioncaremanual.org/topic.<br />

cfm?ncm_category_id=1&lv1=5522&lv2=22684&lv3=269416&n<br />

cm_toc_id=269416&ncm_heading=Nutrition%20Care.<br />

Conclusion<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY – AUTUMN <strong>2023</strong><br />

Currently, a consensus regarding evaluation of CD in patients with nonclassical<br />

symptom presentations does not exist; however, exploration<br />

of CD as a diagnosis is recommended in those presenting with elevated<br />

transaminase levels of unknown etiology (1). Once diagnosed, education<br />

on the risk dietary nonadherence should be routinely emphasized by both<br />

the treating physicians and RDNs. Elevated transaminase and progressive<br />

liver disease is a specific long-term consequence of CD that can easily<br />

be overlooked as both a symptom of the disease and a sign of nonadherence<br />

to a gluten free diet.<br />

References<br />

1. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, Calderwood AH, Murray JA. ACG<br />

clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease.<br />

Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):656-76.<br />

2. Tovoli F, De Giorgio R, Caio G, Grasso V, Frisoni C, Serra M, et al.<br />

Autoimmune Hepatitis and Celiac Disease: Case Report Showing<br />

an Entero-Hepatic Link. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2010;4(3):469-<br />

75.<br />

3. Kaukinen K, Halme L, Collin P, Farkkila M, Maki M, Vehmanen<br />

P, et al. Celiac disease in patients with severe liver disease:<br />

10

Optimising<br />

maintenance therapy<br />

for ulcerative colitis:<br />

Real<br />

choices<br />

When mesalazine doesn’t seem to be working, stepping<br />

up to immunosuppressants isn’t the only option<br />

Together we know more.<br />

Together we do more.<br />

Real<br />

solution<br />

Salofalk Granules are easy to take, they have a<br />

pleasant vanilla flavour, and they’re a proven way to<br />

help patients get the most from their mesalazine 1-3<br />

Optimising therapy with once-daily Salofalk Granules in patients<br />

who were inadequately maintained on previous mesalazine resulted in: 2<br />

69% 45% 50%<br />

fewer<br />

days<br />

off work<br />

fewer<br />

GP visits<br />

due to UC<br />

fewer<br />

steroid<br />

courses used<br />

Mesalazine, the Dr Falk way<br />

Prescribing Information Information (refer (refer to to full full SPC SPC before before prescribing): prescribing):<br />

Salofalk<br />

Presentation:<br />

gastro-resistant<br />

Salofalk 250mg<br />

prolonged-release<br />

gastro-resistant tablets:<br />

granules<br />

gastro-resistant tablet<br />

containing 250mg mesalazine. Salofalk 500mg and 1g gastro-resistant tablet<br />

Presentation: (UK ONLY) containing Stick-formed 500mg or and round, 1g mesalazine greyish white respectively. gastro-resistant Salofalk<br />

prolonged-release 500mg/1000mg/1500mg/3000mg granules in sachets prolonged-release containing granules: 500mg, prolongedrelease<br />

or granules 3g mesalazine containing per 500mg,1000mg, sachet. Indications: 1500mg or Treatment 3000mg mesalazine of acute<br />

1000mg,<br />

1.5g<br />

episodes per sachet. and Indications: the maintenance Salofalk 250mg of remission tablets (UK): of ulcerative treatment colitis. and<br />

Dosage: maintenance Adults: of remission Once daily of 1 mild/moderate sachet of 3g granules, ulcerative 1 colitis. or 2 sachets Salofalk of<br />

1.5g 250mg granules tablets or (Ireland): 3 sachets as of an 1000mg anti-inflammatory 500mg granules in the management (equivalent of to<br />

1.5<br />

ulcerative<br />

– 3.0g<br />

colitis<br />

mesalazine<br />

and in<br />

daily)<br />

the treatment<br />

preferably<br />

of Crohn’s<br />

taken in<br />

disease.<br />

the morning,<br />

Salofalk<br />

according<br />

500mg<br />

tablets (UK): treatment and maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis.<br />

to<br />

Salofalk<br />

individual<br />

1g tablets<br />

clinical<br />

(UK):<br />

requirement.<br />

treatment<br />

May<br />

of acute<br />

be taken<br />

episodes<br />

in three<br />

of mild/moderate<br />

divided doses<br />

(1 ulcerative sachet colitis. of 500mg Salofalk granules granules: three treatment times daily of acute or 1 sachet episodes of 1000mg and the<br />

granules maintenance three of remission times daily) of mild if more to moderate convenient. ulcerative Maintenance: colitis. Dosage: 0.5g<br />

mesalazine Salofalk 250mg three tablets times - Adults daily and elderly: (morning, acute treatment midday 6 -12 and tablets evening) daily<br />

corresponding 3 divided doses. to Maintenance a total dose treatment of 1.5g mesalazine 6 tablets daily per in day. 3 divided For patients doses.<br />

known Salofalk to 500mg be at tablets increased (UK only): risk for 1 relapse or 2 tablets for 3 medical times daily. reasons Maintenance: or due to<br />

difficulties 1 tablet 3 times to adhere daily. Salofalk to three 1g tablets daily doses, (UK only): give 1 tablet 3.0g mesalazine three times daily. as a<br />

Salofalk granules – adults: acute treatment – once daily 1 sachet of 3g<br />

single daily dose, preferably in the morning. Children: There is only<br />

granules, 1 or 2 sachets of Salofalk 1.5g granules, 3 sachets of 500mg<br />

granules limited documentation or 3 sachets of for 1000mg an effect granules in children (equivalent (age to 6-18 1.5 – years). 3.0g<br />

mesalazine Children 6 daily), years preferably of age and taken older: in the Active morning. disease: Alternatively, To be the determined dose can<br />

be individually, taken divided starting three with doses. 30-50mg/kg/day Maintenance treatment once daily – 1 preferably sachet of 500mg in the<br />

granules morning 3 or times in divided daily (1.5g doses. mesalazine Maximum daily). dose: Where 75mg/kg/day. needed, 3.0g per The day total in<br />

a dose single should morning not dose exceed may be taken. the maximum Method of administration: adult dose. Maintenance oral. Tablets<br />

treatment: - taken whole To without be determined chewing, with individually, liquid, one starting hour before with meals. 15-30mg/kg/day Granules<br />

in<br />

- taken<br />

divided<br />

on the<br />

doses.<br />

tongue<br />

The<br />

and<br />

total<br />

swallowed,<br />

dose should<br />

without<br />

not<br />

chewing,<br />

exceed<br />

with<br />

the<br />

plenty<br />

recommended<br />

of liquid.<br />

Duration of treatment is usually 8 weeks. To be determined by physician.<br />

adult<br />

Children<br />

dose.<br />

(all formulations):<br />

It is generally<br />

there<br />

recommended<br />

is only limited<br />

that<br />

documentation<br />

half the adult<br />

for<br />

dose<br />

an effect<br />

may<br />

be in children given to (age children 6-18 years). up to a Children body weight 6 years of and 40kg; older: and active the normal disease – adult on<br />

dose individual to those basis starting above with 40kg. 30-50mg/kg/day Method of administration: either once daily Taken (granules) on the or<br />

tongue in divided and doses swallowed, (tablets and without granules). chewing, Maximum with 75mg/kg/day. plenty of liquid. Total Contraindications:<br />

should not exceed Hypersensitivity recommended to adult salicylates dose. Maintenance or any of the - on excipients. individual<br />

dose<br />

Severe basis starting impairment with 15-30mg/kg/day of renal or hepatic in divided function. doses. Warnings/Precautions:<br />

Total dose should not<br />

Blood<br />

exceed<br />

tests<br />

recommended<br />

and urinary<br />

adult<br />

status<br />

dose.<br />

(dip<br />

Generally<br />

sticks) should<br />

recommended<br />

be determined<br />

that half<br />

prior<br />

the<br />

adult dose may be given to children up to a body weight of 40kg and the<br />

to<br />

normal<br />

and<br />

adult<br />

during<br />

dose<br />

treatment.<br />

to those above<br />

Caution<br />

40kg.<br />

is<br />

Contra-indications:<br />

recommended in<br />

Hypersensitivity<br />

patients with<br />

impaired to salicylates hepatic or any of function. the excipients. Should Severe not impairment be used of in renal patients or hepatic with<br />

impaired function. Warnings/Precautions: renal function. Mesalazine-induced Blood tests and urinary renal toxicity status (dip should sticks) be<br />

considered should be determined if renal function prior deteriorates to and during during treatment. treatment. Caution Cases is of<br />

recommended in patients with impaired hepatic function. Should not be<br />

used in patients with impaired renal function. Mesalazine-induced renal<br />

toxicity should be considered if renal function deteriorates during treatment<br />

- stop treatment immediately in such cases. Cases of nephrolithiasis<br />

reported; ensure good hydration. Serious blood dyscrasias have been<br />

reported very rarely with mesalazine. Hematological investigations should<br />

be performed if patients suffer from unexplained haemorrhages, bruises,<br />

purpura, anaemia, fever or pharyngolaryngeal pain. Salofalk should be<br />

nephrolithiasis<br />

discontinued in case<br />

reported;<br />

of suspected<br />

ensure<br />

or confirmed<br />

good hydration.<br />

blood dyscrasia.<br />

Patients<br />

Cardiac<br />

with<br />

hypersensitivity reactions (myocarditis, and pericarditis) induced by<br />

pulmonary<br />

mesalazine have<br />

disease,<br />

been rarely<br />

in<br />

reported.<br />

particular<br />

Salofalk<br />

asthma,<br />

should<br />

should<br />

then be<br />

be<br />

discontinued<br />

carefully<br />

monitored. immediately. Patients with with pulmonary a history disease, of adverse in particular drug asthma, reactions should to<br />

preparations be carefully monitored. containing Severe sulphasalazine cutaneous should adverse be reactions kept under (SCARs), close<br />

medical including surveillance. drug reaction with If acute eosinophilia intolerance and systemic reactions symptoms e.g., abdominal (DRESS),<br />

cramps, Stevens-Johnson acute abdominal syndrome pain, (SJS) and fever, toxic severe epidermal headache necrolysis and (TEN), rash, occur, have<br />

stop been reported. treatment Discontinue immediately. treatment Severe at the cutaneous first appearance adverse of signs reactions and<br />

(SCARs), symptoms of including severe skin Stevens-Johnson reactions, such as skin syndrome rash, mucosal (SJS) lesions, and or toxic any<br />

other sign of hypersensitivity. Patients with a history of adverse drug reactions<br />

epidermal necrolysis (TEN), have been reported. Discontinue<br />

to preparations containing sulphasalazine should be kept under close<br />

treatment medical surveillance. at the first If appearance acute intolerance of signs reactions and symptoms e.g., abdominal of severe cramps, skin<br />

reactions, acute abdominal such pain, as skin fever, rash, severe mucosal headache lesions, and rash or occur, any stop other treatment sign of<br />

hypersensitivity. immediately. Tablets Salofalk may granules be excreted contain undissolved aspartame, in patients a source with the of<br />

phenylalanine ileocecal valve removed. that may Salofalk be harmful granules: for patients contain with aspartame, phenylketonuria. a source of<br />

Salofalk phenylalanine. granules May contain be harmful sucrose: to patients 0.02mg, with phenylketonuria. 0.04mg, 0.06mg Granules and<br />

0.12mg also contain (500mg/1g/1.5g sucrose: 0.04mg, and 0.08mg, 3g granules 0.12mg, respectively). 0.24mg (500mg/1g/1.5g<br />

Interactions:<br />

Specific<br />

and 3g granules<br />

interaction<br />

respectively).<br />

studies have<br />

Salofalk<br />

not<br />

tablets:<br />

been performed.<br />

For patients on<br />

Lactulose<br />

a sodiumcontrolled<br />

diet: the 250mg and 500mg tablets contain 48mg and 49mg of<br />

or<br />

similar<br />

sodium,<br />

preparations<br />

equivalent to 2.4%<br />

that<br />

and<br />

lower<br />

2.5%<br />

stool<br />

of the recommended<br />

pH: possible<br />

maximum<br />

reduction<br />

daily<br />

of<br />

mesalazine intake for sodium. release Urine from may granules be discoloured due to red-brown decreased after pH contact caused with by<br />

bacterial sodium hypochlorite metabolism bleach of lactulose. used in toilets. With Interactions: concomitant Specific treatment interaction with<br />

azathioprine, studies have not 6-mercaptopurine been performed. or thioguanine With concomitant consider treatment a possible with<br />

increase azathioprine, in their 6-mercaptopurine myelosuppressive or thioguanine, effects. There consider is weak a possible evidence increase that<br />

mesalazine their myelosuppressive might decrease effects. the anticoagulant There is weak effect evidence of warfarin. that mesalazine Use in<br />

pregnancy might decrease and the lactation: anticoagulant There are effect no of adequate warfarin. data. Salofalk Do granules not use<br />

(additionally): lactulose, or similar preparations which lower stool pH:<br />

during pregnancy unless the potential benefit outweighs the possible<br />

possible reduction of mesalazine release from granules due to decreased pH<br />

risks. caused Limited by bacterial experience metabolism in the of lactulose. lactation Use period. in pregnancy Use during and lactation: breastfeeding<br />

do not use only Salofalk if the during potential pregnancy benefit unless outweighs the potential the possible benefit risks; outweighs if the<br />

infant the possible develops risks. Limited diarrhoea, experience breast-feeding the lactation should period. be Salofalk discontinued. should<br />

Undesirable only be used during effects: breast-feeding Headache, if dizziness, the potential peri- benefit and outweighs myocarditis, the<br />

abdominal possible risks; pain, if the diarrhoea, breast-fed dyspepsia, infant develops flatulence, diarrhoea, nausea, breast-feeding vomiting,<br />

aplastic should be discontinued. anaemia, agranulocytosis, Undesirable effects: pancytopenia, altered blood counts neutropenia, (aplastic<br />

leukopenia,<br />

anaemia, agranulocytosis,<br />

thrombocytopenia,<br />

pancytopenia,<br />

peripheral<br />

neutropenia,<br />

neuropathy, allergic<br />

leukopenia,<br />

and<br />

thrombocytopenia), hypersensitivity reactions such as allergic exanthema,<br />

fibrotic<br />

drug fever,<br />

lung<br />

lupus<br />

reactions<br />

erythematosus<br />

(including<br />

syndrome,<br />

dyspnoea,<br />

pancolitis,<br />

cough,<br />

headache,<br />

bronchospasm,<br />

dizziness,<br />

alveolitis, peripheral neuropathy, pulmonary peri- eosinophilia, and myo-carditis, lung infiltration, allergic and pneumonitis), fibrotic lung<br />

acute reactions pancreatitis, (including dyspnoea, impairment cough, of renal bronchospasm, function including alveolitis, pulmonary acute and<br />

chronic eosinophilia, interstitial lung infiltration, nephritis pneumonitis), and renal insufficiency, abdominal nephrolithiasis,<br />

pain, diarrhoea,<br />

dyspepsia, flatulence, nausea, vomiting, acute pancreatitis, cholestatic<br />

hepatitis, hepatitis, rash, pruritus, photosensitivity – especially with preexisting<br />

skin conditions, alopecia, severe cutaneous adverse reactions<br />

(SCARs) including drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms<br />

(DRESS), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis<br />

(TEN), arthralgia, myalgia, impairment of renal function including acute and<br />

chronic interstitial nephritis and renal insufficiency, nephrolithiasis, asthenia,<br />

fatigue, oligospermia (reversible), changes in hepatic function parameters,<br />

photosensitivity<br />

changes in pancreatic<br />

especially<br />

enzymes,<br />

with<br />

eosinophil<br />

pre-existing<br />

count<br />

skin<br />

increased.<br />

conditions,<br />

Legal<br />

alopecia,<br />

category:<br />

POM. Cost (UK - basic NHS price; Ireland - PtW): Salofalk 250mg tablets<br />

Stevens-Johnson<br />

(100s) £16.19; €13.48.<br />

syndrome<br />

Salofalk<br />

(SJS),<br />

500mg<br />

toxic<br />

tablets<br />

epidermal<br />

(100s) £32.38.<br />

necrolysis<br />

Salofalk<br />

(TEN),<br />

1g<br />

myalgia, tablets (90s) arthralgia, £58.50. Salofalk hypersensitivity 500mg granules reactions (100 sachets) such £28.74; as allergic €27.93.<br />

exanthema, Salofalk 1000mg drug granules fever, lupus (50 sachets) erythematosus £28.74; €32.87. syndrome, Salofalk pancolitis, 1500mg<br />

changes granules in (60 hepatic sachets) function £48.85; parameters, €49.66. Salofalk hepatitis, 3g granules cholestatic (60 hepatitis sachets)<br />

and £97.70; oligospermia €101.64. (reversible), Product licence asthenia, number: fatigue, Salofalk changes 250mg in pancreatic tablets:<br />

enzymes, PL10341/0004; eosinophil PA573/4/3. count Salofalk increased. 500mg Legal tablets: category: PL08637/0019. POM. Salofalk Basic<br />

cost: 1g tablets: Salofalk PL08637/0027. 500mg granules, Salofalk pack size 500mg 100 sachets granules: - £28.74; PL08637/0007; €30.39.<br />

PA573/3/1. Salofalk 1000mg granules: PL08637/0008; PA573/3/2. Salofalk<br />

Salofalk 1000mg granules, pack size 50 sachets – £28.74; 32.87€.<br />

1500mg granules: PL08637/0016; PA573/3/7. Salofalk 3g granules:<br />

Salofalk PL08637/0025; 1.5g Granules, PA573/3/6. pack Product size 60 licence sachets holder: - £48.85; Salofalk €50.02. 250mg Salofalk tablets<br />

3g in Granules the UK: Dr pack Falk size Pharma 60 sachets UK Ltd, - Bourne £97.70; End €102.62 Business (UK- Park, NHS Cores price; End IE<br />

- Road, PtW). Bourne Product End, SL8 licence 5AS. Salofalk number: 500mg Salofalk and 1g tablets 500mg and granules all granules: –<br />

PL08637/0007; Dr Falk Pharma GmbH, PA573/3/1. Leinenweberstr.5, Salofalk 1000mg D-79108 granules Freiburg, – PL08637/0008;<br />

Germany. Date<br />

PA573/3/2. of preparation: Salofalk January 1.5g <strong>2023</strong> granules PL08637/0016; PA573/3/7. Salofalk<br />

3g granules PL08637/0025; PA573/3/6.Product licence holder: Dr Falk<br />

Pharma Further GmbH, information Leinenweberstr.5, is available on D-79108 request. Freiburg, Germany. Date of<br />

preparation: January 2022.<br />

Further Adverse information events should is available be reported. on request. In the UK: Reporting forms<br />

and information can be found at https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.<br />

Adverse uk/ In events Ireland: should Reporting be reported. forms Reporting and information forms and can information be found<br />

can at be https://www.hpra.ie/homepage/about-us/report-an-issue/<br />

found at https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/ (UK residents) or in<br />

Ireland human-adverse-reaction-form<br />

at https://www.hpra.ie/homepage/about-us/report-anissue/human-adverse-reaction-form<br />

reported to Dr Falk Pharma UK Ltd Adverse at PV@drfalkpharma.co.uk.<br />

events should also be<br />

Adverse events should also be<br />

reported to Dr Falk Pharma UK Ltd at PV@drfalkpharma.co.uk<br />

References:<br />

References: 1. Salofalk Granules. Summary of Product Characteristics.<br />

1. 2. Salofalk Aldulaimi Granules. D et al. Summary Poster DRF16/057 of Product presented Characteristics. at the<br />

2. Aldulaimi BSG Annual D et Meeting, al. Poster June DRF16/057 2016, Liverpool presented UK. at the BSG Annual<br />

3. Meeting, Keil R et June al. Scand 2016, J Liverpool Gastroenterol UK. 2018; 21: 1-7.<br />

3. Keil R et al. Scand J Gastroenterol 2018; 21: 1-7.<br />

UC: ulcerative colitis<br />

UC: ulcerative colitis<br />

Date of preparation: March <strong>2023</strong><br />

Date<br />

UI--2300070<br />

of preparation: March 2022<br />

UI--2200080<br />

To find out more about Salofalk Granules<br />

watch this 60s animation

FEATURE<br />

FATIGUE IN PATIENTS WITH<br />

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE—<br />

STRONGLY INFLUENCED BY DEPRESSION<br />

AND NOT IDENTIFIABLE THROUGH<br />

LABORATORY TESTING: A CROSS-<br />

SECTIONAL SURVEY STUDY<br />

Victoria Uhlir 1 , Andreas Stallmach 1 and Philip Christian Grunert 1 *<br />

Uhlir et al. BMC <strong>Gastroenterology</strong> (<strong>2023</strong>) 23:288 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02906-0<br />

RESEARCH<br />

Background<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY – AUTUMN <strong>2023</strong><br />

Abstract<br />

Background: Fatigue is a debilitating and highly relevant symptom in<br />

patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). However, awareness of<br />

fatigue and treatment options remains limited. This study was aimed at<br />

elucidating the influence of disease activity and common complications<br />

(pain, anemia, depression, anxiety and quality of life) on fatigue in patients<br />

with IBD to identify potential interventional targets for treating physicians.<br />

Methods: A cross-sectional survey including five questionnaires (HADS,<br />

Fatigue Assessment Scale, McGill Pain Questionnaire, IBDQ and general<br />

well-being) was performed on patients with IBD (n = 250) at a university<br />

IBD clinic. Additionally, demographic data, laboratory data, IBD history,<br />

treatment and current disease activity (Harvey-Bradshaw Index, partial<br />

Mayo Score, calprotectin and CRP) were recorded.<br />

Results: A total of 189 patients were analyzed (59.8% with Crohn’s<br />

disease (CD) and 40.2% with ulcerative colitis (UC)).<br />

A total of 51.3% were fatigued, and 12.2% were extremely fatigued.<br />

Multiple factors showed significant correlations in univariate analysis.<br />