CHAPTER I Global Investment Trends

CHAPTER I Global Investment Trends

CHAPTER I Global Investment Trends

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

36<br />

World <strong>Investment</strong> Report 2011: Non-Equity Modes of International Production and Development<br />

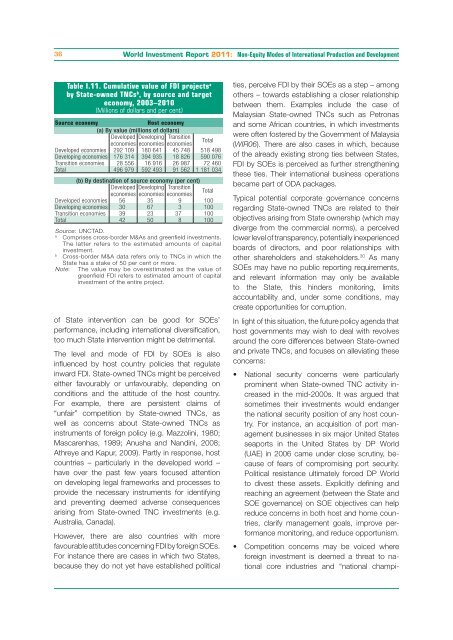

Table I.11. Cumulative value of FDI projects a<br />

by State-owned TNCs b , by source and target<br />

economy, 2003–2010<br />

(Millions of dollars and per cent)<br />

Source economy Host economy<br />

(a) By value (millions of dollars)<br />

Developed Developing Transition<br />

economies economies economies<br />

Total<br />

Developed economies 292 109 180 641 45 748 518 498<br />

Developing economies 176 314 394 935 18 826 590 076<br />

Transition economies 28 556 16 916 26 987 72 460<br />

Total 496 979 592 493 91 562 1 181 034<br />

(b) By destination of source economy (per cent)<br />

Developed Developing Transition<br />

economies economies economies<br />

Total<br />

Developed economies 56 35 9 100<br />

Developing economies 30 67 3 100<br />

Transition economies 39 23 37 100<br />

Total 42 50 8 100<br />

Source: UNCTAD.<br />

a Comprises cross-border M&As and greenfield investments.<br />

The latter refers to the estimated amounts of capital<br />

investment.<br />

b Cross-border M&A data refers only to TNCs in which the<br />

State has a stake of 50 per cent or more.<br />

Note: The value may be overestimated as the value of<br />

greenfield FDI refers to estimated amount of capital<br />

investment of the entire project.<br />

of State intervention can be good for SOEs’<br />

performance, including international diversification,<br />

too much State intervention might be detrimental.<br />

The level and mode of FDI by SOEs is also<br />

influenced by host country policies that regulate<br />

inward FDI. State-owned TNCs might be perceived<br />

either favourably or unfavourably, depending on<br />

conditions and the attitude of the host country.<br />

For example, there are persistent claims of<br />

“unfair” competition by State-owned TNCs, as<br />

well as concerns about State-owned TNCs as<br />

instruments of foreign policy (e.g. Mazzolini, 1980;<br />

Mascarenhas, 1989; Anusha and Nandini, 2008;<br />

Athreye and Kapur, 2009). Partly in response, host<br />

countries – particularly in the developed world –<br />

have over the past few years focused attention<br />

on developing legal frameworks and processes to<br />

provide the necessary instruments for identifying<br />

and preventing deemed adverse consequences<br />

arising from State-owned TNC investments (e.g.<br />

Australia, Canada).<br />

However, there are also countries with more<br />

favourable attitudes concerning FDI by foreign SOEs.<br />

For instance there are cases in which two States,<br />

because they do not yet have established political<br />

ties, perceive FDI by their SOEs as a step – among<br />

others – towards establishing a closer relationship<br />

between them. Examples include the case of<br />

Malaysian State-owned TNCs such as Petronas<br />

and some African countries, in which investments<br />

were often fostered by the Government of Malaysia<br />

(WIR06). There are also cases in which, because<br />

of the already existing strong ties between States,<br />

FDI by SOEs is perceived as further strengthening<br />

these ties. Their international business operations<br />

became part of ODA packages.<br />

Typical potential corporate governance concerns<br />

regarding State-owned TNCs are related to their<br />

objectives arising from State ownership (which may<br />

diverge from the commercial norms), a perceived<br />

lower level of transparency, potentially inexperienced<br />

boards of directors, and poor relationships with<br />

other shareholders and stakeholders. 30 As many<br />

SOEs may have no public reporting requirements,<br />

and relevant information may only be available<br />

to the State, this hinders monitoring, limits<br />

accountability and, under some conditions, may<br />

create opportunities for corruption.<br />

In light of this situation, the future policy agenda that<br />

host governments may wish to deal with revolves<br />

around the core differences between State-owned<br />

and private TNCs, and focuses on alleviating these<br />

concerns:<br />

• National security concerns were particularly<br />

prominent when State-owned TNC activity increased<br />

in the mid-2000s. It was argued that<br />

sometimes their investments would endanger<br />

the national security position of any host country.<br />

For instance, an acquisition of port management<br />

businesses in six major United States<br />

seaports in the United States by DP World<br />

(UAE) in 2006 came under close scrutiny, because<br />

of fears of compromising port security.<br />

Political resistance ultimately forced DP World<br />

to divest these assets. Explicitly defining and<br />

reaching an agreement (between the State and<br />

SOE governance) on SOE objectives can help<br />

reduce concerns in both host and home countries,<br />

clarify management goals, improve performance<br />

monitoring, and reduce opportunism.<br />

• Competition concerns may be voiced where<br />

foreign investment is deemed a threat to national<br />

core industries and “national champi-