antiquarian bookseller - Peter Harrington

antiquarian bookseller - Peter Harrington

antiquarian bookseller - Peter Harrington

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

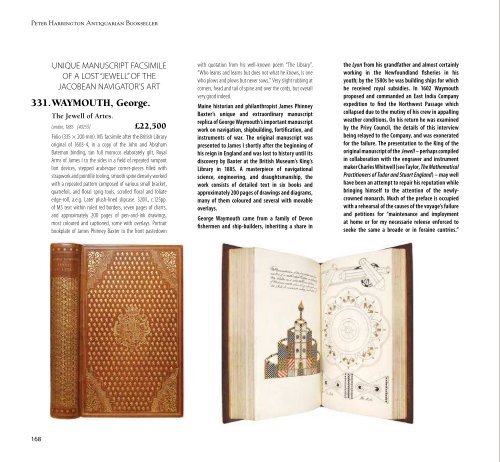

<strong>Peter</strong> <strong>Harrington</strong> Antiquarian Bookseller<br />

168<br />

UNIQUE MANUSCRIPT FACSIMILE<br />

OF A LOST “JEWELL” OF THE<br />

JACOBEAN NAVIGATOR’S ART<br />

331.WAYMOUTH, George.<br />

The Jewell of Artes.<br />

London, 1885 [40255] £22,500<br />

Folio (335 × 200 mm). MS facsimile after the British Library<br />

original of 1603-4, in a copy of the John and Abraham<br />

Bateman binding, tan full morocco elaborately gilt, Royal<br />

Arms of James I to the sides in a field of repeated rampant<br />

lion devices, stepped arabesque corner-pieces filled with<br />

strapwork and pointillé tooling, smooth spine densely worked<br />

with a repeated pattern composed of various small bracket,<br />

quatrefoil, and floral sprig tools, scrolled floral and foliate<br />

edge-roll, a.e.g. Later plush-lined slipcase. 320ll., c.125pp.<br />

of MS text within ruled red borders, seven pages of charts,<br />

and approximately 200 pages of pen-and-ink drawings,<br />

most coloured and captioned, some with overlays. Portrait<br />

bookplate of James Phinney Baxter to the front pastedown<br />

with quotation from his well-known poem “The Library”,<br />

“Who learns and learns but does not what he knows, Is one<br />

who plows and plows but never sows.” Very slight rubbing at<br />

corners, head and tail of spine and over the cords, but overall<br />

very good indeed.<br />

Maine historian and philanthropist James Phinney<br />

Baxter’s unique and extraordinary manuscript<br />

replica of George Waymouth’s important manuscript<br />

work on navigation, shipbuilding, fortification, and<br />

instruments of war. The original manuscript was<br />

presented to James I shortly after the beginning of<br />

his reign in England and was lost to history until its<br />

discovery by Baxter at the British Museum’s King’s<br />

Library in 1885. A masterpiece of navigational<br />

science, engineering, and draughtsmanship, the<br />

work consists of detailed text in six books and<br />

approximately 200 pages of drawings and diagrams,<br />

many of them coloured and several with movable<br />

overlays.<br />

George Waymouth came from a family of Devon<br />

fishermen and ship-builders, inheriting a share in<br />

the Lyon from his grandfather and almost certainly<br />

working in the Newfoundland fisheries in his<br />

youth; by the 1580s he was building ships for which<br />

he received royal subsidies. In 1602 Waymouth<br />

proposed and commanded an East India Company<br />

expedition to find the Northwest Passage which<br />

collapsed due to the mutiny of his crew in appalling<br />

weather conditions. On his return he was examined<br />

by the Privy Council, the details of this interview<br />

being relayed to the Company, and was exonerated<br />

for the failure. The presentation to the King of the<br />

original manuscript of the Jewell – perhaps compiled<br />

in collaboration with the engraver and instrument<br />

maker Charles Whitwell (see Taylor, The Mathematical<br />

Practitioners of Tudor and Stuart England) – may well<br />

have been an attempt to repair his reputation while<br />

bringing himself to the attention of the newlycrowned<br />

monarch. Much of the preface is occupied<br />

with a rehearsal of the causes of the voyage’s failure<br />

and petitions for “maintenance and imployment<br />

at home or for my necessarie releese enforced to<br />

seeke the same a broade or in foraine cuntries.”<br />

In the text he emphasizes “the explorercolonizer’s<br />

need for a knowledge of navigational<br />

instruments, shipbuilding, machinery, gunnery, and<br />

fortification” (ODNB). The six books contain a series<br />

of “demonstrations” of these sciences illustrated by<br />

elaborate diagrams. The most substantial section<br />

is that on “Diverse instruments for navigation”,<br />

including the cross-staff, the quadrant, the astrolabe<br />

and the compass, and techniques “for sea men<br />

to keepe there reckonings of there shippes way.”<br />

The second part is dedicated to “the manner of<br />

building of shipp[s] by A geometrical proportion…<br />

whereby any worke man of mean capacitie having<br />

some small skill in Arithmetick and geometrie” can<br />

avoid error and produce ships both “more offensive<br />

and defensive than those nowe used.” Waymouth’s<br />

“Engines”, include the use of inflated pig-skins to<br />

help soldiers swim over rivers; a turntable device<br />

edged with blades and mounted with “small<br />

murdering pieces which will carry some 40 or 50<br />

muskett bulletes” which can withstand assault and<br />

carry a lethal fire “in to any one, or diverse partes<br />

of the shipp where it is assaulted”, together with<br />

a primitive tank and gunboat for riverine warfare.<br />

A section on various forms of mensuration follows,<br />

how to measure the height of castle walls, the depth<br />

of a well and the “most necessarie Instruments<br />

to survey land with.” The “fifte booke concerning<br />

fortification” contains a series of plans for complex<br />

gun forts and castles, together with instructions on<br />

mining and counter-mining, clearly demonstrating<br />

Waymouth’s belief that the “the practise of<br />

fortification nowe as necessarilie be imployed in the<br />

land of Florida” as in Europe. The final part is on the<br />

manufacture of ordnance and gun-carriages, and<br />

the calculation of trajectories. In all a remarkable<br />

navigator-artificer’s vade mecum, the possibility<br />

of Whitwell’s contribution perhaps underscored by<br />

the reliance on various elaborate “instruments.”<br />

If Waymouth’s highly ingenious gift to the King did<br />

not obtain for him the direct Royal patronage that<br />

he was seeking, it may well have been instrumental<br />

in obtaining him command of another expedition.<br />

Catalogue 57: Travel Section 7: Mapping, Navigation and Naval History<br />

In 1605 he found “sponsors from the worlds of<br />

commerce and colonization: Plymouth merchants<br />

interested in the cod fishery; Sir Thomas Arundell,<br />

who wished to establish an American colony for<br />

Roman Catholics; and possibly Arundell’s brother-inlaw,<br />

the Earl of Southampton” (ODNB). Southampton<br />

had been Essex’s collaborator in the planned rising<br />

against Elizabeth, and on his accession James had<br />

freed him from imprisonment and recreated him as<br />

Earl. Perhaps James had shared the perusal of the<br />

manuscript with his ambitious favourite, who put his<br />

influence behind the mounting of the expedition. In<br />

March 1605 Waymouth set off in the Archangell on a<br />

voyage of exploration and possible colonization. It is<br />

for this exploit that he is primarily known, one of the<br />

earliest European expeditions to coastal Maine, which<br />

is recorded in James Rosier’s A True Relation of the<br />

Most Prosperous Voyage made this Present Yeere 1605<br />

by Captaine George Waymouth… (London, 1605). His<br />

true destination was probably the region between<br />

Chesapeake Bay and Cape Cod, but pushed further<br />

north by bad weather the expedition reached the<br />

George River in present-day Maine in mid-May. They<br />

remained a month in the Georges Islands, where they<br />

traded with the local Abenaki Indians, eventually<br />

capturing and bringing back four of them – together<br />

with the famous Squanto, a visiting Patuxet, who<br />

later served on John Smith’s 1614 voyage to Virginia<br />

– for future use as guides and interpreters. The<br />

expedition opened the way for the establishment of<br />

the short-lived but historically significant Plymouth<br />

Company Popham colony in Maine, founded in 1607.<br />

It was whilst seeking fresh materials on this subject<br />

in the King’s Library that Baxter was introduced,<br />

through serendipity and the hard work of an intrepid<br />

assistant librarian, to the previously misshelved<br />

manuscript of the Jewell: “I followed him and he<br />

took down a large manuscript volume elegantly<br />

bound and laid it before me, entitled Jewell of Artes<br />

by George Waymouth, which was a present by him<br />

to James First. ‘I do not know as this is any interest<br />

to you,’ said Kensington, ‘but as you instructed me<br />

to call your attention to anything possibly relating<br />

to your subjects I thought I would show it to you.’<br />

… I immediately procured an expert to copy<br />

and make facsimiles of the numerous drawings<br />

which the book contained, and the binder of the<br />

Museum had especial tools make that he might<br />

make for a facsimile binding of the original.” On<br />

his return to America Baxter made this replica<br />

available to Henry S. Burrage who was working<br />

on a new edition of Rosier’s account, leading to<br />

a rapid reassessment of Waymouth’s reputation,<br />

from that of “a competent English shipmaster<br />

only”, a “rough and uneducated adventurer”, to<br />

highly competent navigator at home in the worlds<br />

of artificer-scientists and aristocratic patronage.<br />

Waymouth considered the content of this work to be<br />

close to a state secret, stating in his preface – with<br />

perhaps a mingled sense of threat and promise<br />

– that he had withheld it from publication for fear<br />

that “foraine nations, for whome I nothing meant it<br />

should reape as much proffit of it as this my natiue<br />

countrie.” It is unsurprising therefore that the BM<br />

copy remained the only contemporary version<br />

known until 1971, when Henry C. Taylor bequeathed<br />

his library on navigation and the early exploration<br />

of America to the Beinecke. Amongst the collection<br />

was another early 17th-century copy, almost<br />

identical in content and binding to the BM’s, but<br />

unfortunately possessed of no earlier provenance<br />

than that of Taylor. The present manual facsimile<br />

is by all accounts a perfect replica of the British<br />

Museum copy with respect to its text, illustrations<br />

and binding. The only significant differences are<br />

that the text is executed in a neat and clearly legible<br />

Victorian hand rather than crabbed 17th-century<br />

script, and that no attempt was made to duplicate<br />

the original paper. The Jewell of Artes, in both its<br />

original undertaking and this unique manuscript<br />

reproduction, represents major historical moments<br />

of scholarship, craftsmanship, and discovery.<br />

Offered here in the only obtainable copy.<br />

169