Art Ew - National Gallery of Australia

Art Ew - National Gallery of Australia

Art Ew - National Gallery of Australia

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

hermitage. Within a decade Teruhisa and the last <strong>of</strong><br />

Rengetsu’s children had died. The nun then left the temple<br />

to make her own way in the world.<br />

In search <strong>of</strong> a means <strong>of</strong> support, she considered<br />

teaching the board game gõ, which Teruhisa had taught<br />

her, or waka poetry, which she had studied at Kameoka.<br />

(Waka poems have thirty-one syllables divided into five<br />

lines <strong>of</strong> five-seven-five-seven-seven syllables.) Although<br />

neither career was a success, Rengetsu’s verse did<br />

contribute to her later work. In her late forties or early<br />

fifties, Rengetsu began making tea ceramics. In describing<br />

her teapots, Rengetsu modestly wrote, ‘they were very<br />

humble and the shapes were unrefined. The poems I<br />

carved on them I wrote when I had a moment free. I never<br />

had much free time.’ 1<br />

Rengetsu’s combination <strong>of</strong> pottery, poetry and<br />

calligraphy, usually using Japanese kana rather than<br />

Chinese kanji characters, was inspired. These simple,<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten roughly made, objects proved enormously popular.<br />

Though doubtless an exaggeration, it has been said that<br />

Rengetsu made more than 50,000 works in her lifetime<br />

and that every Kyoto household included at least one<br />

example, be it a tea vessel, sweets dish, sake flask or<br />

cup, tanzaku poem sheet, or a painting with calligraphy.<br />

Rengetsu’s work was so popular that even within her<br />

lifetime it was imitated and faked, a practice that has<br />

continued intermittently to the present and which makes<br />

it difficult to confidently attribute many Rengetsustyle<br />

objects to the artist herself. In many ways this is<br />

unimportant as such things did not concern Rengetsu.<br />

She is believed to have willingly helped others make<br />

their ceramics and paintings more saleable by adding her<br />

calligraphy to them. In one story, a ceramics manufacturer<br />

asked Rengetsu to inscribe copies <strong>of</strong> her work because<br />

they couldn’t duplicate her calligraphy. She agreed, even<br />

presenting some originals so better copies could be made.<br />

To keep up with demand for her ceramics, Rengetsu also<br />

worked with pr<strong>of</strong>essional potters, including Isso (dates<br />

unknown) and Kuroda Koryo (1822–1895). Known as<br />

Rengetsu II, Kuroda had Rengetsu’s permission to sign his<br />

work with her name and continued to do so after her death.<br />

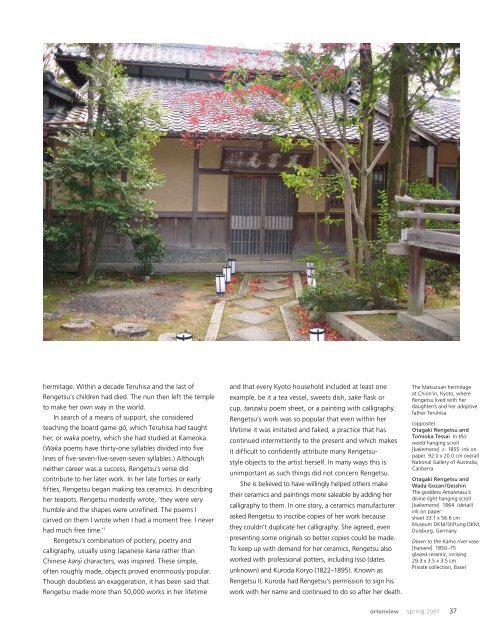

The Makuzuan hermitage<br />

at Chion’in, Kyoto, where<br />

Rengetsu lived with her<br />

daughter/s and her adoptive<br />

father Teruhisa<br />

(opposite)<br />

Otagaki Rengetsu and<br />

Tomioka Tessai In this<br />

world hanging scroll<br />

[kakemono] c. 1855 ink on<br />

paper 92.0 x 20.0 cm overall<br />

<strong>National</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>,<br />

Canberra<br />

Otagaki Rengetsu and<br />

Wada Gozan/Gesshin<br />

The goddess Amaterasu’s<br />

divine light hanging scroll<br />

[kakemono] 1864 (detail)<br />

ink on paper<br />

sheet 33.1 x 56.6 cm<br />

Museum DKM/Stiftung DKM,<br />

Duisburg, Germany<br />

Down to the Kamo river vase<br />

[hanaire] 1850–75<br />

glazed ceramic, incising<br />

29.3 x 3.5 x 3.5 cm<br />

Private collection, Basel<br />

artonview spring 2007 37