Art Ew - National Gallery of Australia

Art Ew - National Gallery of Australia

Art Ew - National Gallery of Australia

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

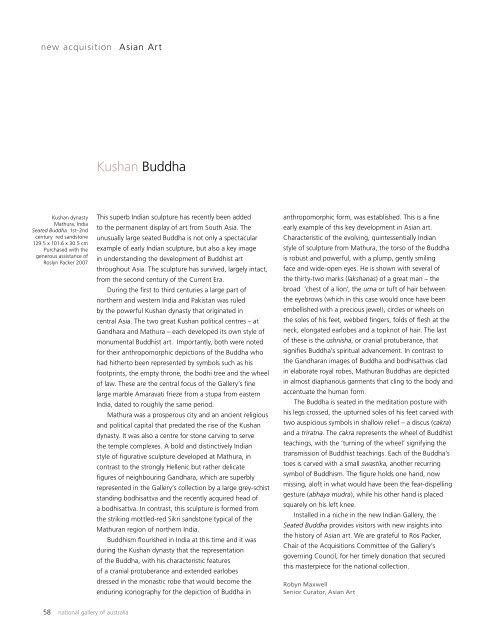

new acquisition Asian <strong>Art</strong><br />

Kushan dynasty<br />

Mathura, India<br />

Seated Buddha 1st–2nd<br />

century red sandstone<br />

129.5 x 101.6 x 30.5 cm<br />

Purchased with the<br />

generous assistance <strong>of</strong><br />

Roslyn Packer 2007<br />

58 national gallery <strong>of</strong> australia<br />

Kushan Buddha<br />

This superb Indian sculpture has recently been added<br />

to the permanent display <strong>of</strong> art from South Asia. The<br />

unusually large seated Buddha is not only a spectacular<br />

example <strong>of</strong> early Indian sculpture, but also a key image<br />

in understanding the development <strong>of</strong> Buddhist art<br />

throughout Asia. The sculpture has survived, largely intact,<br />

from the second century <strong>of</strong> the Current Era.<br />

During the first to third centuries a large part <strong>of</strong><br />

northern and western India and Pakistan was ruled<br />

by the powerful Kushan dynasty that originated in<br />

central Asia. The two great Kushan political centres – at<br />

Gandhara and Mathura – each developed its own style <strong>of</strong><br />

monumental Buddhist art. Importantly, both were noted<br />

for their anthropomorphic depictions <strong>of</strong> the Buddha who<br />

had hitherto been represented by symbols such as his<br />

footprints, the empty throne, the bodhi tree and the wheel<br />

<strong>of</strong> law. These are the central focus <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Gallery</strong>’s fine<br />

large marble Amaravati frieze from a stupa from eastern<br />

India, dated to roughly the same period.<br />

Mathura was a prosperous city and an ancient religious<br />

and political capital that predated the rise <strong>of</strong> the Kushan<br />

dynasty. It was also a centre for stone carving to serve<br />

the temple complexes. A bold and distinctively Indian<br />

style <strong>of</strong> figurative sculpture developed at Mathura, in<br />

contrast to the strongly Hellenic but rather delicate<br />

figures <strong>of</strong> neighbouring Gandhara, which are superbly<br />

represented in the <strong>Gallery</strong>’s collection by a large grey-schist<br />

standing bodhisattva and the recently acquired head <strong>of</strong><br />

a bodhisattva. In contrast, this sculpture is formed from<br />

the striking mottled-red Sikri sandstone typical <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Mathuran region <strong>of</strong> northern India.<br />

Buddhism flourished in India at this time and it was<br />

during the Kushan dynasty that the representation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Buddha, with his characteristic features<br />

<strong>of</strong> a cranial protuberance and extended earlobes<br />

dressed in the monastic robe that would become the<br />

enduring iconography for the depiction <strong>of</strong> Buddha in<br />

anthropomorphic form, was established. This is a fine<br />

early example <strong>of</strong> this key development in Asian art.<br />

Characteristic <strong>of</strong> the evolving, quintessentially Indian<br />

style <strong>of</strong> sculpture from Mathura, the torso <strong>of</strong> the Buddha<br />

is robust and powerful, with a plump, gently smiling<br />

face and wide-open eyes. He is shown with several <strong>of</strong><br />

the thirty-two marks (lakshanas) <strong>of</strong> a great man – the<br />

broad ‘chest <strong>of</strong> a lion’, the urna or tuft <strong>of</strong> hair between<br />

the eyebrows (which in this case would once have been<br />

embellished with a precious jewel), circles or wheels on<br />

the soles <strong>of</strong> his feet, webbed fingers, folds <strong>of</strong> flesh at the<br />

neck, elongated earlobes and a topknot <strong>of</strong> hair. The last<br />

<strong>of</strong> these is the ushnisha, or cranial protuberance, that<br />

signifies Buddha’s spiritual advancement. In contrast to<br />

the Gandharan images <strong>of</strong> Buddha and bodhisattvas clad<br />

in elaborate royal robes, Mathuran Buddhas are depicted<br />

in almost diaphanous garments that cling to the body and<br />

accentuate the human form.<br />

The Buddha is seated in the meditation posture with<br />

his legs crossed, the upturned soles <strong>of</strong> his feet carved with<br />

two auspicious symbols in shallow relief – a discus (cakra)<br />

and a triratna. The cakra represents the wheel <strong>of</strong> Buddhist<br />

teachings, with the ‘turning <strong>of</strong> the wheel’ signifying the<br />

transmission <strong>of</strong> Buddhist teachings. Each <strong>of</strong> the Buddha’s<br />

toes is carved with a small swastika, another recurring<br />

symbol <strong>of</strong> Buddhism. The figure holds one hand, now<br />

missing, al<strong>of</strong>t in what would have been the fear-dispelling<br />

gesture (abhaya mudra), while his other hand is placed<br />

squarely on his left knee.<br />

Installed in a niche in the new Indian <strong>Gallery</strong>, the<br />

Seated Buddha provides visitors with new insights into<br />

the history <strong>of</strong> Asian art. We are grateful to Ros Packer,<br />

Chair <strong>of</strong> the Acquisitions Committee <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Gallery</strong>’s<br />

governing Council, for her timely donation that secured<br />

this masterpiece for the national collection.<br />

Robyn Maxwell<br />

Senior Curator, Asian <strong>Art</strong>