The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia, 1966-1978

The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia, 1966-1978

The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia, 1966-1978

- TAGS

- practice

- yugoslavia

- www.msu.hr

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Davor Matievi<br />

<strong>The</strong> Zagreb Circle<br />

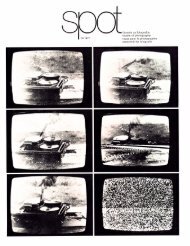

Figs. 47-146<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is a widespread belief <strong>in</strong> the art circles that Zagreb<br />

has ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed a long and un<strong>in</strong>terrupted constructivist<br />

tradition <strong>in</strong> art. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the same op<strong>in</strong>ion, the dom<strong>in</strong>ant<br />

trends before World War II were surrealism M Belgrade,<br />

Expressionism <strong>in</strong> Ljubljana and Constructivism <strong>in</strong> Zagreb,<br />

while after the war the salient trends were the Mediala <strong>in</strong><br />

Belgrade, the lyrical expression of the graphic circle <strong>in</strong><br />

Ljubljana and Exat-51 and the <strong>New</strong> Tendencies <strong>in</strong> Zagreb.<br />

This rough-and-ready div'sion, though basically correct, has<br />

the flaws of all generalizations and its consequences can<br />

still be observed as the same generalizations are be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

applied to the younger generation of artists.<br />

Zagreb is the centre of a comparatively small geographical<br />

area and almost the only scene of activity <strong>in</strong> contemporary<br />

forms of culture <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g v'sual arts. Though always <strong>in</strong><br />

contact with European art centres, ma<strong>in</strong>ly through a number<br />

of artists who were either close to them or formed their part at<br />

least dur<strong>in</strong>g their artistic apprenticeship (s<strong>in</strong>ce the turn of the<br />

century, at least one <strong>in</strong> each generation), this milieu shows<br />

the characterist cs of the <strong>in</strong>ternational art developments coupled<br />

with those of a small town located on the cross-roads between<br />

Central Europe and the Balkans.<br />

We could identify a number of factors that steered the course<br />

of our recent art history <strong>in</strong> this direction. But for the ongo<strong>in</strong>g<br />

period this would be more difficult, because its overall<br />

evaluation is possible only from a greater distance <strong>in</strong> t me.<br />

What is more, the period and the phenomena we want to<br />

present here are still develop<strong>in</strong>g and their mean<strong>in</strong>g still open.<br />

It is difficult to give a decided and def<strong>in</strong>itive assessment of<br />

very recent or current developments from an art h'storian's<br />

po<strong>in</strong>t of view. This can be done by the chronicler and possibly<br />

by the art critic who, however hard they try, can never be<br />

absolutely objective.<br />

<strong>The</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>uation of the constructivist tradition after the<br />

<strong>New</strong> Tendencies period came <strong>in</strong>to question. Introduc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>novations, a whole generation of Zagreb artists utej,<br />

ibenik, Gelid, Kuduz after op-art jo<strong>in</strong>ed the new trends <strong>in</strong><br />

hard-edge pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g, resort<strong>in</strong>g at the same time to the latest<br />

technical achievements. <strong>The</strong>ir work was evaluated aga<strong>in</strong>st ihe<br />

background and qualities of the <strong>New</strong> Tendencies, to which<br />

they reacted by question<strong>in</strong>g the justitcation of the judgment<br />

and by ask<strong>in</strong>g whether they should take part <strong>in</strong> these<br />

activities. <strong>The</strong> next generation of artists, whose work is the<br />

subject of the present survey, did not feel they belonged to<br />

this l<strong>in</strong>e of avant-garde tradition, which they manifested by not<br />

tak<strong>in</strong>g part <strong>in</strong> the <strong>New</strong> Tendenc'es. It is here that we see a<br />

break <strong>in</strong> the cont<strong>in</strong>uity of Constructivism <strong>in</strong> Zagreb, the<br />

emergence of a new attitude to art and a new practice of<br />

artistic behaviour.<br />

Another art movement, the Gorgona, developed almost<br />

simultaneously with the <strong>New</strong> Tendencies, but it was based<br />

on very different pr<strong>in</strong>ciples.<br />

From these and parallel act vities dur<strong>in</strong>g the n<strong>in</strong>eteen sixties<br />

we can s<strong>in</strong>gle out several artists, whose specific characteristics<br />

mark them as predecessors of the current practice of art<br />

associated with the young generation. <strong>The</strong>y are Josip Stoi<br />

and Tomislav Gotovac, whose mediums are poetry and film,<br />

and two representatives of the Gorgona, Julije Knifer and<br />

Ivan Koari. Julije Knifer (Figs. 47-51) is a pa<strong>in</strong>ter, whose<br />

ma<strong>in</strong> motif for twenty years has been the meander, presented Mth<br />

m<strong>in</strong>imal modifications. Over the years this theme has grown<br />

<strong>in</strong>to an <strong>in</strong>dividual work programme, with which it is possible,<br />

on the bas s of various changes <strong>in</strong> art trends, to <strong>in</strong>terpret<br />

almost the same material <strong>in</strong> different ways and it probably<br />

has different mean<strong>in</strong>gs for the artist himself. We can <strong>in</strong>terpret<br />

it as the presentation of a rhythm, as the formation of a<br />

20<br />

super-sign, as hard-edge pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g or the pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

achromatic surfaces with<strong>in</strong> prmary pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g. In his most<br />

recent work the f<strong>in</strong>al product still has its value, but the most<br />

important element for the artist is the procedure and the<br />

last<strong>in</strong>g of the work process <strong>in</strong> the pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g, or <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly<br />

often, the draw<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

<strong>The</strong> repetition of the same motif, a comb<strong>in</strong>ed result of the<br />

artist's programme and his <strong>in</strong>ner compulsion, l<strong>in</strong>ks Knifer<br />

with the new generation of artists more closely than his projects<br />

of <strong>in</strong>tervention and the unique action of pa<strong>in</strong>tng a gigantic<br />

meander <strong>in</strong> quarry near TOb<strong>in</strong>gen (Fig. 50).<br />

<strong>The</strong> sculptor Ivan Koari (Figs. 52-57), on the other hand, is<br />

subject to constant changes, not on the plan of a discernible<br />

programmatic activity but <strong>in</strong> a perpetual search for new<br />

possibilites of expression for his unchang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terpretations<br />

or even literal portrayal of his immediate surround<strong>in</strong>gs, objects,<br />

ideas and associations. From cars and teapots to parts of the<br />

river, ra<strong>in</strong> and space he shapes and remodels at the same<br />

time, he pa<strong>in</strong>ts and accumulates or simply re-arranges his works,<br />

thus re-<strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g old and new experience. Rs numerous<br />

early landscape and urban projects of <strong>in</strong>tervention seem to<br />

express a need to give back to the environment his enriched<br />

and processed experience. By record<strong>in</strong>g ideas he makes<br />

abstractions tangible: examples of such works are Shapes of<br />

Space, Temporary Sculptures, the latter made from foil, which<br />

the audience was allowed to re-shape, or more precisely,<br />

to re-organize, and Former Sculptures (Fig. 53), the<br />

scattered rema'ns of a previous work, which he exhibited<br />

<strong>in</strong>stead of mak<strong>in</strong>g new ones. His new attitude to art enables<br />

the audience to experience a hitherto unknown dimension <strong>in</strong><br />

which the medium itself becomes a problem, which is a common<br />

characteristic of the new generation of artists.<br />

Josip Stoi (Figs. 58-61), an art historian, concerns us here<br />

primarily as a poet. who is not <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> the dist<strong>in</strong>ctions<br />

between fields and media but turns all his attention to the<br />

structures of mental processes. Very early on he saw the<br />

possibility of creat<strong>in</strong>g a new language by comb<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g words,<br />

objects and space. <strong>The</strong> result were some of the most<br />

acceptable works of the new practice of art (A/Vrror and stone<br />

with text: or, then, Fig. 60). Hav<strong>in</strong>g produced an active<br />

<strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> the spectator and placed him <strong>in</strong>to the position of<br />

active creator, Stoi offered him a number of projects for<br />

completion. However, the majority of his works exist only <strong>in</strong> the<br />

form of notes, known to a small circle of f r-ends. He<br />

communicates his experiences by creat<strong>in</strong>g an awareness and<br />

atmosphere through direct contact rather than by produc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

works that could <strong>in</strong>fluence the work of the new generation of<br />

artists.<br />

Tomislav Gotovac has worked mostly <strong>in</strong> film and has not<br />

had direct l<strong>in</strong>ks with the f<strong>in</strong>e arts, but his very early procedures<br />

and behaviour (1960), <strong>in</strong> whch he stressed his own person<br />

<strong>in</strong> various situations, may be considered together with the<br />

works of other predecessors as the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of a new form of<br />

art, the more so because he still uses similar procedures <strong>in</strong><br />

register<strong>in</strong>g various processes of his personal experiential<br />

sphere. H s photo-notes and the series entitled: Heads (Fig. 222),<br />

<strong>The</strong> Presentation of ELLE, Pos<strong>in</strong>g, which were produced <strong>in</strong><br />

Zagreb and Belgrade and only recently shown to the public,<br />

may be classified by the orig<strong>in</strong> of the idea either as film art<br />

or as the new visual art <strong>in</strong> the narrower sense. One of his<br />

works, however, was known to a group of f<strong>in</strong>e artists at the<br />

time of its creation. It was a happen<strong>in</strong>g entitled Our Hap (Fig.<br />

221) and performed with Ivan Lukas and Hrvoje ercar and a<br />

photo mods] <strong>in</strong> Zagreb <strong>in</strong> 1967. And yet, its <strong>in</strong>fluence was not<br />

transmitted by the f<strong>in</strong>e artists who were among the audience<br />

arid some of whom even partic pated <strong>in</strong> the happen<strong>in</strong>g, and<br />

even less by the scanty comment <strong>in</strong> the press, but orally, and<br />

particularly thanks to Hrvoje ercar. Somewhat later the same<br />

year Sercar acted as the <strong>in</strong>itiator of a more dynamic.<br />

behaviour <strong>in</strong> the already heightened atmosphere of the<br />

Hit-Parade (an exhibition of objects by Gelid, Kuduz, utej<br />

and ibenik at the Students' Centre Gallery, Fig. 64), where he