- Page 1 and 2: Towards a [ ] ADVANCE COPY ONLINE R

- Page 3: Towards a Pathways to Sustainable D

- Page 7: Foreword Nearly 20 years after the

- Page 11 and 12: Introduction Setting the stage for

- Page 13 and 14: Contents Introduction 1 Introductio

- Page 15 and 16: policies, including pricing and reg

- Page 17 and 18: one form of capital to meet today

- Page 19 and 20: will be required to assess and moni

- Page 21 and 22: Box 1: Towards a green economy: A t

- Page 23 and 24: overall transition to a green econo

- Page 25 and 26: References Adelman, Irma (1999).

- Page 27: Introduction 27

- Page 30 and 31: iStockphoto/Klaus Hollitzer

- Page 32 and 33: 32 Acknowledgements Chapter Coordin

- Page 34 and 35: Towards a green economy 34 List of

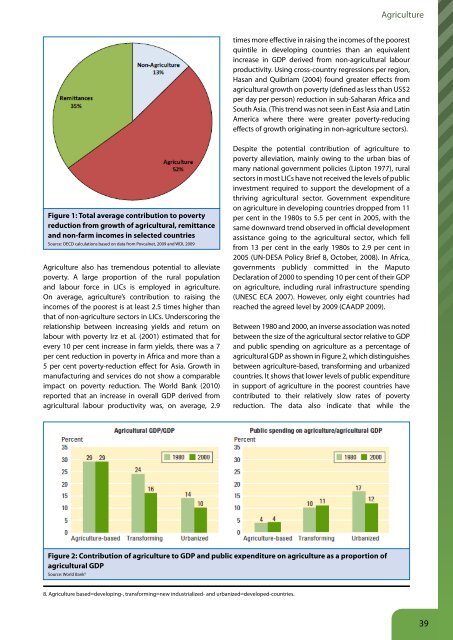

- Page 36 and 37: Towards a green economy 36 Key mess

- Page 40 and 41: Towards a green economy 40 contribu

- Page 42 and 43: Towards a green economy 42 instance

- Page 44 and 45: Towards a green economy 44 2 Challe

- Page 46 and 47: Towards a green economy 46 Figure 8

- Page 48 and 49: Towards a green economy 48 2°C). F

- Page 50 and 51: Towards a green economy 50 3 The ca

- Page 52 and 53: Towards a green economy 52 Box 4: C

- Page 54 and 55: Towards a green economy 54 Improvin

- Page 56 and 57: Towards a green economy 56 Box 8: O

- Page 58 and 59: Towards a green economy 58 is almos

- Page 60 and 61: Towards a green economy 60 Overall,

- Page 62 and 63: Towards a green economy 62 small fa

- Page 64 and 65: Towards a green economy 64 telemetr

- Page 66 and 67: Towards a green economy 66 friendly

- Page 68 and 69: Towards a green economy 68 Annex 2.

- Page 70 and 71: Towards a green economy 70 Annex 3.

- Page 72 and 73: Towards a green economy 72 Referenc

- Page 74 and 75: Towards a green economy 74 Irz, X.,

- Page 76 and 77: Towards a green economy 76 Singh, H

- Page 78 and 79: iStockphoto/Nico Smit

- Page 80 and 81: Towards a green economy 80 Acknowle

- Page 82 and 83: Towards a green economy 82 List of

- Page 84 and 85: Towards a green economy 84 Key mess

- Page 86 and 87: Towards a green economy 86 1 Introd

- Page 88 and 89:

Towards a green economy 88 Fishing

- Page 90 and 91:

Towards a green economy 90 1950s Th

- Page 92 and 93:

Towards a green economy 92 most sig

- Page 94 and 95:

Towards a green economy 94 Item (un

- Page 96 and 97:

Towards a green economy 96 Current

- Page 98 and 99:

Towards a green economy 98 and recr

- Page 100 and 101:

Towards a green economy 100 special

- Page 102 and 103:

Towards a green economy 102 limits

- Page 104 and 105:

Towards a green economy 104 success

- Page 106 and 107:

Towards a green economy 106 private

- Page 108 and 109:

Towards a green economy 108 Referen

- Page 110 and 111:

Towards a green economy 110 Perry,

- Page 112 and 113:

iStockphoto/Morgan Mansour

- Page 114 and 115:

Towards a green economy 114 Acknowl

- Page 116 and 117:

Towards a green economy 116 List of

- Page 118 and 119:

Towards a green economy 118 Key mes

- Page 120 and 121:

Towards a green economy 120 1 Intro

- Page 122 and 123:

Towards a green economy 122 1 5 The

- Page 124 and 125:

Towards a green economy 124 Another

- Page 126 and 127:

Towards a green economy 126 3 Chall

- Page 128 and 129:

Towards a green economy 128 Little

- Page 130 and 131:

water withdrawals, assuming no e�

- Page 132 and 133:

Towards a green economy 132 Biome/e

- Page 134 and 135:

Towards a green economy 134 Accessi

- Page 136 and 137:

Towards a green economy 136 China -

- Page 138 and 139:

Towards a green economy 138 5 Enabl

- Page 140 and 141:

Towards a green economy 140 Regions

- Page 142 and 143:

Towards a green economy Total retur

- Page 144 and 145:

Towards a green economy 144 % 100 9

- Page 146 and 147:

Towards a green economy 146 devolve

- Page 148 and 149:

Towards a green economy 148 6 Concl

- Page 150 and 151:

Towards a green economy 150 linkage

- Page 152 and 153:

iStockphoto/Fenykepez

- Page 154 and 155:

Towards a green economy 154 Acknowl

- Page 156 and 157:

Towards a green economy 156 List of

- Page 158 and 159:

Towards a green economy 158 Key mes

- Page 160 and 161:

Towards a green economy 160 1 Intro

- Page 162 and 163:

Towards a green economy 162 Scope E

- Page 164 and 165:

Towards a green economy 164 more so

- Page 166 and 167:

Towards a green economy 166 Box 3:

- Page 168 and 169:

Towards a green economy 168 still c

- Page 170 and 171:

Towards a green economy 170 the per

- Page 172 and 173:

Towards a green economy 172 forests

- Page 174 and 175:

Towards a green economy 174 The two

- Page 176 and 177:

Towards a green economy 176 or cabl

- Page 178 and 179:

Towards a green economy 178 tropica

- Page 180 and 181:

Towards a green economy 180 Type of

- Page 182 and 183:

Towards a green economy 182 with di

- Page 184 and 185:

Towards a green economy 184 Million

- Page 186 and 187:

Towards a green economy 186 5 Enabl

- Page 188 and 189:

Towards a green economy 188 Box 13:

- Page 190 and 191:

Towards a green economy 190 However

- Page 192 and 193:

Towards a green economy 192 Referen

- Page 194 and 195:

Towards a green economy 194 forests

- Page 197 and 198:

Part II Investing in energy and res

- Page 199 and 200:

Renewable energy Investing in energ

- Page 201 and 202:

Contents Renewable energy Key messa

- Page 203 and 204:

Renewable energy 203

- Page 205 and 206:

Renewable energy 7. Increasing inve

- Page 207 and 208:

non-OECD countries are also expecte

- Page 209 and 210:

About half of these costs will be b

- Page 211 and 212:

efficiency in low-income countries,

- Page 213 and 214:

derived from fossil fuels. The scen

- Page 215 and 216:

US$ (2008) per MWh 9,0 8,0 7,0 6,0

- Page 217 and 218:

US$ billion 80 Growth: 48% 48% 34%

- Page 219 and 220:

study in Aragon, Spain, for example

- Page 221 and 222:

spans of power plants and distribut

- Page 223 and 224:

Mtoe/yr 20000 15000 10000 5000 0 13

- Page 225 and 226:

Effects on employment - increasing

- Page 227 and 228:

Country Renewable energy technology

- Page 229 and 230:

More formal Less formal Stage 1 R&D

- Page 231 and 232:

GDP/capita (thousand 2008 US$) 95 8

- Page 233 and 234:

The challenge of adapting the curre

- Page 235 and 236:

References AFREPREN/FWD Energy, Env

- Page 237 and 238:

WHO (2009): “The Poor man’s fue

- Page 239 and 240:

Manufacturing Investing in energy a

- Page 241 and 242:

Contents Manufacturing Key messages

- Page 243 and 244:

Manufacturing 243

- Page 245 and 246:

Manufacturing 5. While direct job e

- Page 247 and 248:

Aluminium global mass �ow in �n

- Page 249 and 250:

Historically, GDP has grown more ra

- Page 251 and 252:

Gigabarrels annually 40 30 20 10 0

- Page 253 and 254:

Against this background, resource-i

- Page 255 and 256:

Source: Adapted from Mannan (2009),

- Page 257 and 258:

Manufacturing 3 Opportunities - Str

- Page 259 and 260:

Production side Eco-efficiency stra

- Page 261 and 262:

The major obstacle to re-manufactur

- Page 263 and 264:

Table 6: Examples of investment and

- Page 265 and 266:

the impact of greener practices on

- Page 267 and 268:

As suggested by the USA auto indust

- Page 269 and 270:

labor intensity, also due to the fa

- Page 271 and 272:

6 Enabling conditions for a green t

- Page 273 and 274:

principles of industrial symbiosis

- Page 275 and 276:

debate on sector approaches provide

- Page 277 and 278:

impacts of paper, plastic and cloth

- Page 279 and 280:

7 Conclusions This chapter has prov

- Page 281 and 282:

References ABB Switzerland Ltd., Az

- Page 283 and 284:

Renzetti, S. (2005). «Economic Ins

- Page 285 and 286:

Waste Investing in energy and resou

- Page 287 and 288:

Contents Key messages. . . . . . .

- Page 289 and 290:

Waste 289

- Page 291 and 292:

illion in 2008 and projected to gro

- Page 293 and 294:

■ Energy recovery, which harnesse

- Page 295 and 296:

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 GDP per capita (USD) 45

- Page 297 and 298:

200 150 100 1980 Index: 1980=100 19

- Page 299 and 300:

In developing countries, owing to l

- Page 301 and 302:

Percentage 1980 100 80 60 40 20 0 U

- Page 303 and 304:

Targets Examples Resource efficienc

- Page 305 and 306:

Particulars Low-income countries Mi

- Page 307 and 308:

Box 3: Cost savings and resource re

- Page 309 and 310:

Box 5: Turning urban manure into or

- Page 311 and 312:

Renewable waste Thousand TeraJoule

- Page 313 and 314:

Peru (1) and Uruguay (1), has been

- Page 315 and 316:

illion for G2. The allocation for w

- Page 317 and 318:

Transition (CEIT) in complying with

- Page 319 and 320:

waste handling, storage, treatment

- Page 321 and 322:

and standards. Developing countries

- Page 323 and 324:

References Acurio G., Rossin A., Te

- Page 325 and 326:

hod=view&docSeq=194&bbsCode=res_mat

- Page 327 and 328:

Waste 327

- Page 329 and 330:

Buildings Investing in energy and r

- Page 331 and 332:

Contents Buildings Key messages 334

- Page 333 and 334:

Buildings 333

- Page 335 and 336:

Buildings 4. Greening the building

- Page 337 and 338:

2 Challenges and opportunities 2 1

- Page 339 and 340:

Some aspects of improved well-being

- Page 341 and 342:

penetration at certain times of day

- Page 343 and 344:

New construction potential 10 8 6 4

- Page 345 and 346:

3 The case for investment in green

- Page 347 and 348:

new residential construction, an es

- Page 349 and 350:

Box 3: Retrofitting existing office

- Page 351 and 352:

as noise pollution, chemical pollut

- Page 353 and 354:

such as distributing cooking stoves

- Page 355 and 356:

Speanding category Impact Amount (m

- Page 357 and 358:

Scenarios Emission intensity - CO e

- Page 359 and 360:

4 Enabling conditions and policy in

- Page 361 and 362:

Box 7: Reliable measurement and acc

- Page 363 and 364:

water, indoor air quality and finan

- Page 365 and 366:

energy reduction targets had been p

- Page 367 and 368:

5 Conclusions The building sector s

- Page 369 and 370:

References ADB (2009). ARM090554 In

- Page 371 and 372:

Addressing a multi-faceted phenomen

- Page 373 and 374:

Transport Investing in energy and r

- Page 375 and 376:

Contents Transport Key messages 378

- Page 377 and 378:

List of acronyms ADB ‑ Asian Deve

- Page 379 and 380:

Transport 4. Investment in public t

- Page 381 and 382:

2 Challenges and opportunities in t

- Page 383 and 384:

Region* GNP, 1997 (USD billion) Tab

- Page 385 and 386:

Strategy Developed Countries Develo

- Page 387 and 388:

3 Transport in a green economy This

- Page 389 and 390:

Avoid - Shift - Improve Avoid Avoid

- Page 391 and 392:

4 Quantifying the economic implicat

- Page 393 and 394:

Index of emissions (1990 = 100) 160

- Page 395 and 396:

Total employment in the transport s

- Page 397 and 398:

Outer Middle Business-as-usual (dis

- Page 399 and 400:

Funding stream Avoid Shift Improve

- Page 401 and 402:

■ Equity - both horizontally (i.e

- Page 403 and 404:

efficiency measures at a global sca

- Page 405 and 406:

References ADB (2009b) Transport Op

- Page 407 and 408:

VTPI (2007) Transportation Cost and

- Page 409 and 410:

Tourism Investing in energy and res

- Page 411 and 412:

Contents Acknowledgements 410 Key m

- Page 413 and 414:

List of acronyms BAU - Business-as-

- Page 415 and 416:

Tourism 6. Tourists are demanding t

- Page 417 and 418:

2 Challenges and opportunities for

- Page 419 and 420:

Loss of biological diversity There

- Page 421 and 422:

fees. WTP for entrance fees from in

- Page 423 and 424:

For the EU 27, GHK (2007) estimates

- Page 425 and 426:

Tourist RM300 100% tourism incomes

- Page 427 and 428:

that overall financial cost-recover

- Page 429 and 430:

US$1 billion and a significantly hi

- Page 431 and 432:

4 Overcoming barriers: enabling con

- Page 433 and 434:

a selection of larger firms. Smalle

- Page 435 and 436:

Tourism investment from government

- Page 437 and 438:

and bankers. Long-term contracts fo

- Page 439 and 440:

y sustainable local, small, medium,

- Page 441 and 442:

Annex 2: Drivers and likely implica

- Page 443 and 444:

Annex 3: Assumptions of the model 1

- Page 445 and 446:

References Adamson, M. (2001): “E

- Page 447:

Tourism 447

- Page 450 and 451:

Towards a green economy 450 Acknowl

- Page 452 and 453:

Towards a green economy 452 List of

- Page 454 and 455:

Towards a green economy 454 Key mes

- Page 456 and 457:

Towards a green economy 456 1 Intro

- Page 458 and 459:

Towards a green economy 458 Nationa

- Page 460 and 461:

Towards a green economy 460 of ener

- Page 462 and 463:

Towards a green economy 462 3 The c

- Page 464 and 465:

Towards a green economy 464 compare

- Page 466 and 467:

Towards a green economy 466 Fifth,

- Page 468 and 469:

Towards a green economy 468 ■ Psy

- Page 470 and 471:

Towards a green economy 470 4 Green

- Page 472 and 473:

Towards a green economy 472 cities

- Page 474 and 475:

Towards a green economy 474 capita

- Page 476 and 477:

Towards a green economy 476 on wate

- Page 478 and 479:

Towards a green economy 478 Environ

- Page 480 and 481:

Towards a green economy 480 Second,

- Page 482 and 483:

Towards a green economy 482 Referen

- Page 484 and 485:

Towards a green economy 484 America

- Page 486 and 487:

Towards a green economy 486 Appendi

- Page 488 and 489:

Towards a green economy 488 [access

- Page 491:

Part III Supporting the transition

- Page 494 and 495:

Towards a green economy 494 Acknowl

- Page 496 and 497:

Towards a green economy 496 List of

- Page 498 and 499:

Towards a green economy 498

- Page 500 and 501:

Towards a green economy 500 Key mes

- Page 502 and 503:

Towards a green economy 502 1 Intro

- Page 504 and 505:

Towards a green economy 504 scarce

- Page 506 and 507:

Towards a green economy 506 Environ

- Page 508 and 509:

Towards a green economy 508 BAU Sce

- Page 510 and 511:

Towards a green economy 510 to the

- Page 512 and 513:

Towards a green economy 512 Million

- Page 514 and 515:

Towards a green economy 514 depend

- Page 516 and 517:

Towards a green economy 516 Natural

- Page 518 and 519:

Towards a green economy 518 Box 1:

- Page 520 and 521:

Towards a green economy 520 Percent

- Page 522 and 523:

Towards a green economy 522 Billion

- Page 524 and 525:

Towards a green economy 524 BAU U (

- Page 526 and 527:

Towards a green economy 526 Million

- Page 528 and 529:

Towards a green economy 528 Thousan

- Page 530 and 531:

Towards a green economy 530 Economi

- Page 532 and 533:

Towards a green economy 532 2011 20

- Page 534 and 535:

Towards a green economy 534 2015 20

- Page 536 and 537:

Towards a green economy 536 Society

- Page 538 and 539:

Towards a green economy 538 added a

- Page 540 and 541:

Towards a green economy 540 interve

- Page 543 and 544:

Enabling conditions Supporting the

- Page 545 and 546:

Contents Enabling conditions Key me

- Page 547 and 548:

Enabling conditions 4. A well-desig

- Page 549 and 550:

2 Key policy tools The sections bel

- Page 551 and 552:

Box 1: Investing in green infrastru

- Page 553 and 554:

For example, depending on the suppo

- Page 555 and 556:

provides countries with the ability

- Page 557 and 558:

environmentally harmful in other ca

- Page 559 and 560:

considers key national regulatory t

- Page 561 and 562:

MEAs can play a significant role in

- Page 563 and 564:

application of new technologies in

- Page 565 and 566:

3 Supporting actions Depending on t

- Page 567 and 568:

are able to learn and understand th

- Page 569 and 570:

Annex 1 - Enabling conditions: A se

- Page 571 and 572:

Enabling condition Rationale: How i

- Page 573 and 574:

National Ecology Institute of Mexic

- Page 575 and 576:

Finance Supporting the transition t

- Page 577 and 578:

Contents Key messages 580 Finance 1

- Page 579 and 580:

List of acronyms A/R Afforestation

- Page 581 and 582:

Finance 4. Advances in disclosure a

- Page 583 and 584:

2 The state of play 2 1 The scale o

- Page 585 and 586:

Global market size Share committed

- Page 587 and 588:

3 Emerging investment in the green

- Page 589 and 590:

increasingly affect the context wit

- Page 591 and 592:

Box 2: Overview of REDD+ Reducing E

- Page 593 and 594:

to learn how a cap-and-trade system

- Page 595 and 596:

£/tCO2e 250 200 150 100 50 £40 0

- Page 597 and 598:

Box 5: Financial materiality and fi

- Page 599 and 600:

to investment, but progress in putt

- Page 601 and 602:

policy makers. The risk pooling aff

- Page 603 and 604:

elevant to both the insurance and i

- Page 605 and 606:

example, it has been established th

- Page 607 and 608:

enchmarking. Public and private ban

- Page 609 and 610:

Exchanges that have taken such init

- Page 611 and 612:

green venture capital funds in deve

- Page 613 and 614:

green subsidies, grants and subsidi

- Page 615 and 616:

own resources to leverage the finan

- Page 617 and 618:

Strengthening the resilience of the

- Page 619:

Finance 619

- Page 622 and 623:

Towards a green economy 622 Conclus

- Page 624:

Towards a green economy 624 the lat