Untitled - Les chemins du Baroque

Untitled - Les chemins du Baroque

Untitled - Les chemins du Baroque

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

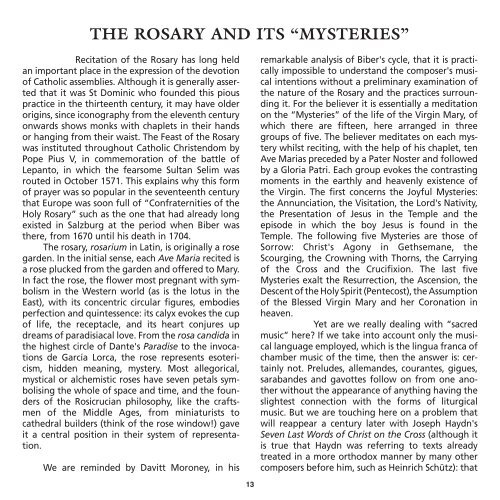

ThE ROSARY And ITS “MYSTERIES”<br />

Recitation of the Rosary has long held<br />

an important place in the expression of the devotion<br />

of Catholic assemblies. Although it is generally asserted<br />

that it was St Dominic who founded this pious<br />

practice in the thirteenth century, it may have older<br />

origins, since iconography from the eleventh century<br />

onwards shows monks with chaplets in their hands<br />

or hanging from their waist. The Feast of the Rosary<br />

was instituted throughout Catholic Christendom by<br />

Pope Pius V, in commemoration of the battle of<br />

Lepanto, in which the fearsome Sultan Selim was<br />

routed in October 1571. This explains why this form<br />

of prayer was so popular in the seventeenth century<br />

that Europe was soon full of “Confraternities of the<br />

Holy Rosary” such as the one that had already long<br />

existed in Salzburg at the period when Biber was<br />

there, from 1670 until his death in 1704.<br />

The rosary, rosarium in Latin, is originally a rose<br />

garden. In the initial sense, each Ave Maria recited is<br />

a rose plucked from the garden and offered to Mary.<br />

In fact the rose, the flower most pregnant with symbolism<br />

in the Western world (as is the lotus in the<br />

East), with its concentric circular figures, embodies<br />

perfection and quintessence: its calyx evokes the cup<br />

of life, the receptacle, and its heart conjures up<br />

dreams of paradisiacal love. From the rosa candida in<br />

the highest circle of Dante's Paradise to the invocations<br />

de García Lorca, the rose represents esotericism,<br />

hidden meaning, mystery. Most allegorical,<br />

mystical or alchemistic roses have seven petals symbolising<br />

the whole of space and time, and the founders<br />

of the Rosicrucian philosophy, like the craftsmen<br />

of the Middle Ages, from miniaturists to<br />

cathedral builders (think of the rose window!) gave<br />

it a central position in their system of representation.<br />

We are reminded by Davitt Moroney, in his<br />

13<br />

remarkable analysis of Biber's cycle, that it is practically<br />

impossible to understand the composer's musical<br />

intentions without a preliminary examination of<br />

the nature of the Rosary and the practices surrounding<br />

it. For the believer it is essentially a meditation<br />

on the “Mysteries” of the life of the Virgin Mary, of<br />

which there are fifteen, here arranged in three<br />

groups of five. The believer meditates on each mystery<br />

whilst reciting, with the help of his chaplet, ten<br />

Ave Marias preceded by a Pater Noster and followed<br />

by a Gloria Patri. Each group evokes the contrasting<br />

moments in the earthly and heavenly existence of<br />

the Virgin. The first concerns the Joyful Mysteries:<br />

the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Lord's Nativity,<br />

the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple and the<br />

episode in which the boy Jesus is found in the<br />

Temple. The following five Mysteries are those of<br />

Sorrow: Christ's Agony in Gethsemane, the<br />

Scourging, the Crowning with Thorns, the Carrying<br />

of the Cross and the Crucifixion. The last five<br />

Mysteries exalt the Resurrection, the Ascension, the<br />

Descent of the Holy Spirit (Pentecost), the Assumption<br />

of the Blessed Virgin Mary and her Coronation in<br />

heaven.<br />

Yet are we really dealing with “sacred<br />

music” here? If we take into account only the musical<br />

language employed, which is the lingua franca of<br />

chamber music of the time, then the answer is: certainly<br />

not. Preludes, allemandes, courantes, gigues,<br />

sarabandes and gavottes follow on from one another<br />

without the appearance of anything having the<br />

slightest connection with the forms of liturgical<br />

music. But we are touching here on a problem that<br />

will reappear a century later with Joseph Haydn's<br />

Seven Last Words of Christ on the Cross (although it<br />

is true that Haydn was referring to texts already<br />

treated in a more orthodox manner by many other<br />

composers before him, such as Heinrich Schütz): that