Profil et contextualisation des pratiques de GRH dans les PME ...

Profil et contextualisation des pratiques de GRH dans les PME ...

Profil et contextualisation des pratiques de GRH dans les PME ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ASAC 2007<br />

Ottawa, Ontario<br />

Richard Lacoursière<br />

Bruno Fabi<br />

Louis Raymond<br />

Département <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> Sciences <strong>de</strong> la gestion<br />

Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières<br />

PROFIL ET CONTEXTUALISATION DES PRATIQUES DE <strong>GRH</strong><br />

DANS LES <strong>PME</strong> MANUFACTURIÈRES 2<br />

S’inspirant <strong>de</strong> la théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes ouverts <strong>et</strong> <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes adaptatifs<br />

complexes, la présente étu<strong>de</strong> a pour but <strong>de</strong> vérifier si l’on peut observer<br />

<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> variations significatives <strong>dans</strong> <strong>les</strong> profils <strong>de</strong> systèmes <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> adoptés<br />

par <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> en fonction <strong>de</strong> leur contexte environnemental,<br />

organisationnel <strong>et</strong> technologique. L’analyse <strong>de</strong> données révèle la présence<br />

<strong>de</strong> trois profils distincts, <strong>les</strong>quels s’avèrent associés à différents éléments<br />

contextuels.<br />

Introduction<br />

L’ouverture <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> marchés, l’intensification <strong>de</strong> la concurrence, l’essor technologique <strong>et</strong> <strong>les</strong><br />

changements démographiques survenus au cours <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>de</strong>rnières décennies ont contribué à modifier <strong>les</strong><br />

conditions <strong>de</strong> réussite <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> entreprises, obligeant plusieurs d’entre el<strong>les</strong> à réviser leurs stratégies, leur<br />

structure <strong>et</strong> leurs façons <strong>de</strong> faire (Snow, Mi<strong>les</strong> <strong>et</strong> Coleman, 1992; T<strong>et</strong>enbaum, 1998). Le fait qu’el<strong>les</strong><br />

constituent <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> organisations « collées » à leur environnement oblige <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> à s’adapter rapi<strong>de</strong>ment aux<br />

pressions <strong>et</strong> aux contraintes qui en émanent tout comme el<strong>les</strong> doivent s’adapter aussi à différents facteurs<br />

internes (facteurs humains <strong>et</strong> organisationnels) relatifs à l’organisation (p. ex., taille, sta<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong><br />

développement, système <strong>de</strong> production), à sa stratégie <strong>et</strong> à sa structure (Fabi <strong>et</strong> Lacoursière, à paraître;<br />

Harney <strong>et</strong> Dundon, 2006).<br />

L’adaptation aux différents facteurs <strong>de</strong> leurs environnements interne <strong>et</strong> externe oblige <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> à<br />

procé<strong>de</strong>r à <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> ajustements <strong>de</strong> toutes sortes, y compris au niveau <strong>de</strong> la <strong>GRH</strong>. La façon dont s’opèrent ces<br />

ajustements a donné lieu à un important courant <strong>de</strong> littérature coloré par <strong>les</strong> divergences entre <strong>les</strong> tenants<br />

<strong>de</strong> l’approche universaliste <strong>et</strong> ceux <strong>de</strong> l’approche <strong>de</strong> contingence. L’approche universaliste voudrait que<br />

<strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>les</strong> plus reconnues <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> aient un eff<strong>et</strong> positif chaque fois qu’on <strong>les</strong> applique. Suivant ce<br />

modèle, le simple fait d’appliquer une ou plusieurs <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> pourrait influencer directement la<br />

performance d’une entreprise (Fabi, Raymond <strong>et</strong> Lacoursière, 2007). C<strong>et</strong>te approche a également été<br />

désignée sous <strong>les</strong> appellations <strong>de</strong> « best practices » <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> « one best way » (Delery <strong>et</strong> Doty, 1996;<br />

McMahan, Virick <strong>et</strong> Wrigth, 1999; Colbert, 2004). Pour sa part, l’approche <strong>de</strong> contingence propose <strong>de</strong><br />

nuancer l’approche universaliste <strong>et</strong> suggère que <strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>, pour être efficaces, doivent s’aligner<br />

avec la stratégie d’affaires (Mi<strong>les</strong> <strong>et</strong> Snow, 1984; Schuler <strong>et</strong> Jackson, 1987). Tel que discuté par<br />

Venkatraman (1989), différents types d’alignement sont possib<strong>les</strong>, chacun faisant appel à une perspective<br />

spécifique d’alignement (<strong>de</strong> « fit ») <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> variab<strong>les</strong> étudiées (dont la perspective « fit as gestalts »).<br />

2 Les auteurs tiennent à remercier le Programme <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> chaires <strong>de</strong> recherche du Canada dont le soutien<br />

financier a permis la réalisation <strong>de</strong> c<strong>et</strong>te recherche.<br />

45

L’approche <strong>de</strong> configuration, que l’on différencie parfois <strong>de</strong> l’approche <strong>de</strong> contingence <strong>dans</strong> la recherche<br />

en <strong>GRH</strong> (Delery <strong>et</strong> Doty, 1996), est ici assimilée à c<strong>et</strong>te <strong>de</strong>rnière, dont elle ne se distingue pas réellement<br />

d’un point <strong>de</strong> vue conceptuel (Schuler <strong>et</strong> Jackson, 2005).<br />

Les approches universaliste <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> contingence ont toutes <strong>de</strong>ux fait l’obj<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> critiques, la première<br />

à cause principalement <strong>de</strong> son caractère simpliste, la secon<strong>de</strong> parce qu’elle ne prend le plus souvent en<br />

considération qu’une seule variable <strong>de</strong> contingence, soit la stratégie. Or comme le mentionne Purcell<br />

(2004, cité <strong>dans</strong> Paauwe <strong>et</strong> Boselie, 2005 : 74), il n’y a guère d’évi<strong>de</strong>nce empirique démontrant<br />

l’importance d’associer <strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> à la stratégie, surtout lorsque celle-ci est définie en termes<br />

simplistes tels que innovation, qualité <strong>et</strong> réduction <strong>de</strong> coûts.<br />

Au cours <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>de</strong>rnières années, <strong>les</strong> approches universaliste <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> contingence ont été<br />

graduellement délaissées en faveur d’une nouvelle approche qui perm<strong>et</strong>tait <strong>de</strong> <strong>les</strong> intégrer toutes <strong>de</strong>ux,<br />

soit la théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> ressources (« resource-based view » ou RBV). Comme l’ont démontré Hansen <strong>et</strong><br />

Wernerfelt (1989), le succès <strong>et</strong> le développement d’une entreprise ne reposerait pas tant sur le choix d’une<br />

industrie en croissance ou d’une niche privilégiée, que sur la construction d’une organisation humaine<br />

efficace au sein <strong>de</strong> l’industrie choisie. La théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> ressources, à laquelle Wernerfelt (1984) a largement<br />

contribué, s’est enrichie <strong>de</strong> plusieurs contributions, dont cel<strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong> Prahalad <strong>et</strong> Hamel (1990), Barney<br />

(1991), P<strong>et</strong>eraf (1993) ainsi que Teece, Pisano <strong>et</strong> Shuen (1997), pour n’en mentionner que quelques-unes.<br />

Suivant c<strong>et</strong>te théorie, <strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> tel<strong>les</strong> que recrutement, formation, participation, évaluation du<br />

ren<strong>de</strong>ment, récompenses <strong>et</strong> autres, contribueraient au cœur <strong>de</strong> métier <strong>de</strong> l’entreprise en agissant à la fois<br />

sur son capital intellectuel, sa gestion <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> connaissances <strong>et</strong> sa capacité <strong>de</strong> renouvellement, sources<br />

d’avantage concurrentiel (Wright, Dunford <strong>et</strong> Snell, 2001).<br />

En dépit <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> possibilités intéressantes qu’elle offre pour argumenter à propos du caractère<br />

stratégique <strong>de</strong> la <strong>GRH</strong>, la théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> ressources n’en fait pas moins elle aussi l’obj<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> critiques<br />

importantes. Truss (2002) soulève par exemple <strong>les</strong> difficultés reliées aux postulats inhérents à c<strong>et</strong>te<br />

théorie <strong>et</strong> relatifs à la rationalité, aux déterminants du comportement humain, à l’applicabilité aux<br />

humains <strong>de</strong> la définition <strong>de</strong> « ressources » <strong>et</strong> à l’importance accordée aux caractéristiques internes <strong>de</strong><br />

l’entreprise. Pour sa part, Colbert (2004) élabore longuement sur la difficulté <strong>de</strong> représenter adéquatement<br />

certains aspects <strong>de</strong> la théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> ressources qui gagneraient, selon lui, à être analysés plutôt <strong>dans</strong> le cadre<br />

<strong>de</strong> la théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes adaptatifs complexes (« complex adaptive systems »).<br />

En parcourant la documentation académique récente, on constate que <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> appels répétés sont<br />

lancés en faveur d’une approche davantage holiste ou systémique <strong>de</strong> la <strong>GRH</strong> (Colbert, 2004; Harney <strong>et</strong><br />

Dundon, 2006; Marlow, 2006; Martin-Alcazar, Romero-Fernan<strong>de</strong>z <strong>et</strong> Sanchez-Gar<strong>de</strong>y, 2005; Paauwe <strong>et</strong><br />

Boselie 2005; Schuler <strong>et</strong> Jackson, 2005). Globalement, ces auteurs insistent sur la nécessité <strong>de</strong> prendre en<br />

considération différents éléments <strong>de</strong> contexte susceptib<strong>les</strong> d’influencer, voire même <strong>de</strong> contraindre <strong>les</strong><br />

choix <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. Les approches systémiques supposent toutefois que l’on tienne compte d’un grand nombre<br />

<strong>de</strong> variab<strong>les</strong> susceptib<strong>les</strong> d’interagir <strong>de</strong> façon non linéaire; leur intérêt consiste davantage à enrichir la<br />

compréhension <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> interrelations entre différentes variab<strong>les</strong> en présence, tant à l’intérieur d’un système<br />

que <strong>dans</strong> son environnement externe, qu’à établir <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> relations <strong>de</strong> cause à eff<strong>et</strong> (Mathews, White <strong>et</strong> Long,<br />

1999 ; Truss, 2001). La présente recherche s’inscrit <strong>dans</strong> une telle perspective <strong>et</strong> vise à explorer <strong>dans</strong><br />

quelle mesure <strong>les</strong> systèmes <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> appliqués <strong>dans</strong> <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> manufacturières peuvent être mis en relation<br />

avec d’autres éléments <strong>de</strong> leurs environnements interne <strong>et</strong> externe.<br />

46

Cadre conceptuel<br />

L’un <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> courants importants ayant caractérisé l’étu<strong>de</strong> <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> organisations au cours <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> trente<br />

<strong>de</strong>rnières années a consisté à reconnaître <strong>de</strong> plus en plus explicitement certaines dimensions <strong>de</strong><br />

l’environnement qui influencent la constitution <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> organisations. Selon Scott (2004), c<strong>et</strong> axe <strong>de</strong><br />

recherche serait largement attribuable à la théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes ouverts, qui a mis en lumière l’importance<br />

<strong>de</strong> l’environnement <strong>dans</strong> lequel opèrent différents systèmes, allant <strong>de</strong> la cellule au système solaire (von<br />

Bertalanffy, 1956).<br />

La théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes ouverts a donné lieu selon Scott (2004) à une prolifération d’approches<br />

visant à expliquer <strong>les</strong> déterminants <strong>de</strong> la structure <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> organisations, dont <strong>les</strong> approches <strong>de</strong> : la théorie <strong>de</strong><br />

la contingence (Woodward, 1958; Lawrence <strong>et</strong> Lorsch, 1967), la théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> coûts <strong>de</strong> transaction<br />

(Williamson, 1975, 1985), la théorie <strong>de</strong> la dépendance en ressources (Pfeffer <strong>et</strong> Salancik, 1978), la théorie<br />

<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> réseaux (White, Boorman <strong>et</strong> Breiger, 1976), l’écologie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> organisations (Hannan <strong>et</strong> Freeman, 1977)<br />

<strong>et</strong> la théorie institutionnelle (Di Maggio <strong>et</strong> Powell, 1983; Meyer <strong>et</strong> Rowan, 1977). Chacune <strong>de</strong> ces<br />

approches a développé <strong>de</strong> nouveaux arguments perm<strong>et</strong>tant d’expliquer comment certains facteurs<br />

environnementaux pourraient interagir avec <strong>les</strong> organisations <strong>et</strong> contribuer à <strong>les</strong> façonner.<br />

Les déterminants <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong><br />

Dans le champ spécifique <strong>de</strong> la <strong>GRH</strong>, une recension <strong>de</strong> la documentation scientifique perm<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong><br />

constater qu’au cours <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> 15 <strong>de</strong>rnières années, plus d’une quarantaine d’étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> empiriques ont cherché à<br />

i<strong>de</strong>ntifier <strong>les</strong> déterminants <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes ou <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> <strong>et</strong>, <strong>dans</strong> certains cas, <strong>de</strong> la<br />

formalisation <strong>de</strong> ces systèmes ou <strong>pratiques</strong>. Les trois variab<strong>les</strong> <strong>les</strong> plus fréquemment analysées <strong>dans</strong> ces<br />

étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> sont, <strong>dans</strong> l’ordre, la taille <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> entreprises (23 étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong>), <strong>les</strong> stratégies d’affaires (16 étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong>) <strong>et</strong> la<br />

présence syndicale (12 étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong>). Parmi <strong>les</strong> autres variab<strong>les</strong> – analysées moins fréquemment cel<strong>les</strong>-là –<br />

figurent le secteur d’activité, <strong>les</strong> caractéristiques du propriétaire, la concurrence, la clientèle, le sta<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong><br />

développement, la technologie, l’âge, <strong>les</strong> caractéristiques <strong>de</strong> la main-d’oeuvre, la présence d’un<br />

responsable RH <strong>et</strong> le caractère familial <strong>de</strong> l’entreprise. Les paragraphes qui suivent donnent un aperçu<br />

très sommaire <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> résultats obtenus relativement à certaines <strong>de</strong> ces variab<strong>les</strong>. Les annexes 1 <strong>et</strong> 2<br />

fournissent <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> informations supplémentaires en ce qui concerne <strong>les</strong> étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> empiriques recensées.<br />

Taille. La taille <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> entreprises exercerait une influence à la fois sur la diversité <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>et</strong><br />

sur leur <strong>de</strong>gré <strong>de</strong> formalisation (Bacon, Ackers, Storey <strong>et</strong> Coates, 1996; Heneman <strong>et</strong> Berkley, 1999;<br />

Kotey <strong>et</strong> Sla<strong>de</strong>, 2005; Wagar, 1998). La désignation d’un responsable <strong>de</strong> la fonction RH surviendrait<br />

lorsque le nombre d’employés atteint une centaine environ (Baron, Hannan <strong>et</strong> Burton, 1999).<br />

Stratégie. Les <strong>PME</strong> misant sur l’innovation <strong>et</strong> sur la qualité auraient tendance à investir<br />

davantage <strong>dans</strong> différentes <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> liées au recrutement, à la formation, à l’évaluation du<br />

ren<strong>de</strong>ment, à la participation <strong>et</strong> à la rémunération incitative (Aragon-Sanchez <strong>et</strong> Sanchez-Marin, 2005;<br />

Bayo-Mariones <strong>et</strong> Merino-Diaz <strong>de</strong> Cerio, 2004; Mak <strong>et</strong> Akhtar, 2003; Sanz-Valle, Sabater-Sanchez <strong>et</strong><br />

Aragon-Sanchez, 1999). Les étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> cherchant à associer certaines <strong>pratiques</strong> spécifiques <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> à <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

profils stratégiques bien définis (p. ex., Prospecteur, Analyste <strong>et</strong> Défenseur <strong>dans</strong> la typologie <strong>de</strong> Mi<strong>les</strong> <strong>et</strong><br />

Snow, 1978) donnent cependant <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> résultats mitigés (Peck, 1994; Raghuram <strong>et</strong> Arvey, 1994).<br />

Présence syndicale. Les étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> ayant cherché à mesurer l’impact <strong>de</strong> la présence d’un syndicat sur<br />

l’application d’une ou <strong>de</strong> plusieurs <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> donnent <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> résultats divergents, certaines ayant<br />

constaté une relation positive (Chowhan, 2005; Turcotte, Léonard <strong>et</strong> Montmarqu<strong>et</strong>te, 2003; Wagar, 1998)<br />

d’autres, une relation nulle (Bayo-Mariones <strong>et</strong> Merino-Diaz <strong>de</strong> Cerio, 2004; Knoke <strong>et</strong> Kalleberg, 1994;<br />

47

Machin <strong>et</strong> Wood, 2005) <strong>et</strong> d’autres enfin une relation négative (Kok <strong>et</strong> Uhlaner, 2001; Shah <strong>et</strong> Ward,<br />

2003).<br />

Propriétaire (dirigeant). À cause <strong>de</strong> l’influence prépondérante dont ils jouissent <strong>dans</strong> <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong>,<br />

<strong>les</strong> propriétaires auraient le pouvoir <strong>de</strong> façonner <strong>les</strong> systèmes <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> en fonction <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> caractéristiques (p.<br />

ex., âge, sexe, formation), <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> valeurs <strong>et</strong> <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> croyances (p. ex., philosophie <strong>de</strong> gestion) qui leur sont<br />

propres (Bacon, Ackers, Storey <strong>et</strong> Coates, 1996; Baron, Hannan <strong>et</strong> Burton, 1999; Matlay, 1999; Mazzarol,<br />

2003; Verheul, Risseeuw <strong>et</strong> Bartelse, 2002).<br />

Clientèle. Les <strong>PME</strong> faisant affaires avec un nombre restreint <strong>de</strong> clients ou encore avec un grand<br />

donneur d’ordres peuvent se voir contraintes d’adopter <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> façons <strong>de</strong> faire dictées par leur clientèle.<br />

Suivant <strong>les</strong> étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> empiriques recensées, <strong>les</strong> exigences <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> clients en matière, notamment, <strong>de</strong> qualité <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

produits <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> délais <strong>de</strong> livraison (juste-à-temps), obligeraient <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> à intensifier la formation <strong>de</strong> leurs<br />

employés <strong>et</strong> à revoir leur mo<strong>de</strong> d’organisation du travail (Beaumont, Hunter <strong>et</strong> Sinclair, 1996; Kinnie,<br />

Purcell, Hutchinson, Terry, Collinson <strong>et</strong> Scarbrough, 1999; Swart <strong>et</strong> Kinnie, 2003).<br />

Sta<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> développement.. Les besoins <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> entreprises en matière <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> peuvent varier en<br />

fonction du sta<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> développement auquel el<strong>les</strong> en sont arrivées. Nonobstant leur taille, <strong>les</strong> entreprises<br />

peuvent faire face à <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> priorités différentes selon qu’el<strong>les</strong> sont en sta<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> démarrage, d’expansion, <strong>de</strong><br />

consolidation ou <strong>de</strong> diversification (Budhwar <strong>et</strong> Khatri, 2001; Hanks <strong>et</strong> Chandler, 1994; Rutherford,<br />

Buller <strong>et</strong> McMullen, 2003; Soci<strong>et</strong>y for Human Resource Management, 2002).<br />

Technologie. La technologie utilisée <strong>dans</strong> <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> peut avoir pour eff<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>les</strong> inciter à<br />

développer davantage certaines <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. On a ainsi observé que <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> recourant à <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

technologies <strong>de</strong> production sophistiquées (advanced manufacturing technologies) <strong>et</strong> à une approche <strong>de</strong><br />

gestion <strong>de</strong> la qualité étaient davantage susceptib<strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong> dispenser <strong>de</strong> la formation <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> m<strong>et</strong>tre en place <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

<strong>pratiques</strong> favorisant la participation (Bayo-Mariones <strong>et</strong> Merino-Diaz <strong>de</strong> Cerio, 2004; Chowhan, 2005;<br />

Poutsma <strong>et</strong> Hendrickx, 2003; Turcotte, Léonard <strong>et</strong> Montmarqu<strong>et</strong>te, 2003).<br />

Responsable RH. On comprendra assez aisément que la présence d’un responsable RH puisse<br />

influencer le niveau <strong>de</strong> développement <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. Le fait <strong>de</strong> disposer à l’interne d’un<br />

responsable désigné pour la prise en charge <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> différentes activités <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> perm<strong>et</strong> aux entreprises <strong>de</strong><br />

mieux planifier, diversifier <strong>et</strong> formaliser <strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> liées par exemple au recrutement, à la sélection, à<br />

l’information, à la formation <strong>et</strong> à l’évaluation du ren<strong>de</strong>ment (Heneman <strong>et</strong> Berkley, 1999; Way <strong>et</strong> Thacker,<br />

2004).<br />

Il ressort donc clairement <strong>de</strong> la documentation empirique que plusieurs variab<strong>les</strong> contextuel<strong>les</strong><br />

pourraient influencer <strong>les</strong> systèmes <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> en contexte <strong>de</strong> <strong>PME</strong>. S’appuyant sur la théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes<br />

ouverts, la théorie institutionnelle (Di Maggio <strong>et</strong> Powell, 1983; Paauwe, 2004) <strong>et</strong> la théorie <strong>de</strong> la<br />

dépendance <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> ressources (Pfeffer <strong>et</strong> Salancik, 1978; Jackson <strong>et</strong> Schuler, 1995) Harney <strong>et</strong> Dundon<br />

(2006) ont proposé récemment un modèle d’analyse reprenant plusieurs <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> variab<strong>les</strong> énumérées ci<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong>sus.<br />

Suivant le modèle proposé, différentes variab<strong>les</strong> caractérisant l’environnement externe <strong>et</strong> la<br />

dynamique interne <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> organisations perm<strong>et</strong>traient <strong>de</strong> mieux comprendre l’émergence <strong>et</strong> l’évolution <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

systèmes <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. Discutant <strong>les</strong> résultats <strong>de</strong> leur étu<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> cas réalisée auprès <strong>de</strong> six <strong>PME</strong>, Harney <strong>et</strong><br />

Dundon (2006) constatent que la <strong>GRH</strong> s’y avère façonnée par une interaction complexe <strong>de</strong> facteurs<br />

internes <strong>et</strong> externes, ce qui leur fait dire que la <strong>GRH</strong> pourrait être davantage réactive que stratégique.<br />

D’autres chercheurs ayant analysé <strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> en <strong>PME</strong> sont arrivés à <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> conclusions similaires<br />

(Cassel, Nadin, Gray <strong>et</strong> Clegg, 2002; Katz, Aldrich, Welbourne <strong>et</strong> Williams, 2000), ce qui perm<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong><br />

croire qu’en contexte <strong>de</strong> <strong>PME</strong>, une approche (réactive) <strong>de</strong> système ouvert conviendrait peut-être mieux à<br />

l’analyse <strong>de</strong> la <strong>GRH</strong> que <strong>les</strong> autres approches (contingence, configuration, RBV), qui sont davantage<br />

teintées <strong>de</strong> rationalité <strong>et</strong> qui supposent un niveau d’expertise en <strong>GRH</strong> dont peu <strong>de</strong> <strong>PME</strong> disposent.<br />

48

Tel qu’ils le précisent, Harney <strong>et</strong> Dundon (2006 :53) n’ont pas cherché à i<strong>de</strong>ntifier <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> patterns <strong>de</strong><br />

comportement au sein <strong>de</strong> leur échantillon, mais plutôt à mieux comprendre <strong>les</strong> motifs justifiant <strong>les</strong> choix<br />

effectués. La présente recherche propose d’apporter un éclairage complémentaire en vérifiant si <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

patterns <strong>de</strong> comportement <strong>GRH</strong> sont observab<strong>les</strong> <strong>dans</strong> un échantillon <strong>de</strong> <strong>PME</strong> compte tenu <strong>de</strong> différents<br />

facteurs internes <strong>et</strong> externes susceptib<strong>les</strong> d’influencer le développement <strong>de</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> ou d’ensemb<strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. Plus précisément, c<strong>et</strong>te recherche tentera <strong>de</strong> répondre aux <strong>de</strong>ux questions suivantes :<br />

1) Peut-on distinguer différents profils <strong>de</strong> comportement <strong>GRH</strong> <strong>dans</strong> <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> manufacturières ?<br />

2) Si oui, ces profils <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> sont-ils associés à <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> éléments contextuels d’ordre environnemental,<br />

organisationnel ou technologique ?<br />

La figure 1 illustre le modèle <strong>de</strong> recherche utilisé. On y distingue, d’une part, une série <strong>de</strong><br />

variab<strong>les</strong> contextuel<strong>les</strong> tirées <strong>de</strong> la documentation empirique <strong>et</strong>, d’autre part, une série <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> potentiellement associées à ces variab<strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong> contexte.<br />

Figure 1<br />

Éléments <strong>de</strong> contexte environnemental, organisationnel <strong>et</strong> technologique pouvant<br />

influencer le comportement <strong>GRH</strong> <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>PME</strong> manufacturières<br />

CONTEXTE<br />

ENVIRONNEMENTAL<br />

Secteur<br />

Clientèle<br />

CONTEXTE<br />

ORGANISATIONNEL<br />

Taille<br />

Stratégie<br />

Structure<br />

<strong>Profil</strong>s <strong>de</strong><br />

comportement <strong>GRH</strong><br />

<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>PME</strong> manufacturières<br />

Dirigeant<br />

CONTEXTE<br />

TECHNOLOGIQUE<br />

Technologie<br />

Métho<strong>de</strong><br />

Les informations requises concernant <strong>les</strong> variab<strong>les</strong> contextuel<strong>les</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> ont été<br />

puisées <strong>dans</strong> une base <strong>de</strong> données créée par un centre <strong>de</strong> recherche universitaire. C<strong>et</strong>te base <strong>de</strong> données<br />

contient <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> informations provenant <strong>de</strong> quelque 300 <strong>PME</strong> manufacturières canadiennes comptant entre 6<br />

<strong>et</strong> 405 employés. On y trouve <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> informations relatives à plus <strong>de</strong> 850 variab<strong>les</strong> généra<strong>les</strong> <strong>et</strong> financières,<br />

recueillies à partir d’un questionnaire d’informations confi<strong>de</strong>ntiel<strong>les</strong> auquel <strong>les</strong> répondants <strong>de</strong>vaient<br />

joindre <strong>les</strong> états financiers <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> cinq <strong>de</strong>rniers exercices. Les entreprises sont contactées directement pour<br />

fournir leurs informations généra<strong>les</strong> <strong>et</strong> financières en échange d’un diagnostic sur leur situation générale.<br />

Ce processus <strong>de</strong> cueill<strong>et</strong>te d’information assure une gran<strong>de</strong> fiabilité à la base <strong>de</strong> données utilisée. Les<br />

entreprises <strong>de</strong> moins <strong>de</strong> 20 employés <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> plus <strong>de</strong> 249 employés ont été éliminées <strong>de</strong> façon à obtenir un<br />

échantillon <strong>de</strong> <strong>PME</strong> dont la taille correspon<strong>de</strong> aux définitions européenne <strong>et</strong> nord-américaine. C<strong>et</strong>te façon<br />

49

<strong>de</strong> procé<strong>de</strong>r a permis d’obtenir un échantillon <strong>de</strong> 176 entreprises dont la taille varie entre 20 <strong>et</strong> 233<br />

employés, la médiane se situant à 50 employés.<br />

Mesures<br />

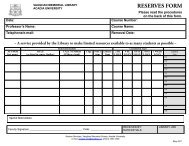

Les sept variab<strong>les</strong> contextuel<strong>les</strong> apparaissant <strong>dans</strong> le modèle <strong>de</strong> recherche sont mesurées au<br />

moyen <strong>de</strong> quinze indicateurs. Le secteur d’activité est mesuré par le niveau d’intensité technologique; la<br />

clientèle (dépendance commerciale), par le pourcentage <strong>de</strong> ventes effectuées auprès <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> 3 principaux<br />

clients <strong>et</strong> la taille, par le nombre d’employés. La stratégie est mesurée au moyen <strong>de</strong> trois indicateurs, soit<br />

le développement <strong>de</strong> réseaux, le développement <strong>de</strong> produits <strong>et</strong> le développement <strong>de</strong> marchés; il en va <strong>de</strong><br />

même pour la structure, mesurée par la présence d’un conseil d’administration, la présence d’un syndicat<br />

<strong>et</strong> la présence d’un responsable RH. La technologie est mesurée suivant <strong>de</strong>ux dimensions, soit le type <strong>de</strong><br />

production (mesuré par <strong>de</strong>ux indicateurs, soit le pourcentage <strong>de</strong> production sous forme <strong>de</strong> p<strong>et</strong>its lots <strong>et</strong> la<br />

présence <strong>de</strong> normes <strong>de</strong> qualité.) <strong>et</strong> le niveau <strong>de</strong> maîtrise du système <strong>de</strong> fabrication (mesuré par trois<br />

indicateurs, soit <strong>les</strong> technologies <strong>de</strong> conception, <strong>de</strong> fabrication <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> planification). Enfin, en ce qui<br />

concerne le dirigeant, une seule caractéristique est mesurée, soit le niveau <strong>de</strong> scolarité.<br />

Le niveau <strong>de</strong> développement <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> a été mesuré en considérant l’étendue<br />

d’application <strong>de</strong> 10 <strong>pratiques</strong>, soit cel<strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong> : <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong>criptions <strong>de</strong> tâches, recrutement, évaluation du<br />

ren<strong>de</strong>ment, formation, diffusion d’information (stratégique, économique <strong>et</strong> opérationnelle), participation<br />

aux décisions <strong>et</strong> rémunération incitative (participation aux profits <strong>et</strong> accès à la propriété). Pour <strong>les</strong><br />

<strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> recrutement, <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong>criptions <strong>de</strong> tâches, évaluation du ren<strong>de</strong>ment, participation aux profits <strong>et</strong><br />

accès à la propriété, l’étendue (<strong>de</strong> 0 à 5) a été mesurée à partir du nombre <strong>de</strong> catégories <strong>de</strong> personnel<br />

(cadres, employés <strong>de</strong> bureaux, représentants, contremaîtres, employés <strong>de</strong> production) touchées par<br />

l’application <strong>de</strong> la pratique. Pour la pratique <strong>de</strong> participation aux décisions, l’étendue a été mesurée en<br />

tenant compte <strong>de</strong> la nature <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> consultations effectuées auprès <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> employés <strong>de</strong> production pour <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> décisions<br />

concernant la gestion <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> opérations (1 = informés après <strong>les</strong> faits, 2 = informés avant <strong>les</strong> faits, 3 = consultés, 4<br />

= partenaires <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> décisions, 5 = mandatés pour prendre <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> décisions). L’étendue <strong>de</strong> la diffusion<br />

d’information a été mesurée pour trois types d’information (stratégique, économique, opérationnelle)<br />

comportant entre 3 <strong>et</strong> 6 indicateurs chacun <strong>et</strong> pouvant faire l’obj<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> diffusion auprès <strong>de</strong> quatre catégories<br />

d’employés. Ainsi, l’information stratégique comportait quatre indicateurs (mission, objectifs, résultats <strong>de</strong><br />

productivité, résultats financiers), pouvant faire l’obj<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> diffusion auprès <strong>de</strong> quatre catégories d’employés;<br />

l’information économique comportait trois indicateurs <strong>et</strong> l’étendue <strong>de</strong> l’information opérationnelle comportait<br />

six indicateurs. En ce qui concerne la pratique <strong>de</strong> formation, l’étendue a été mesurée par le ratio du budg<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong><br />

formation par rapport aux ventes tota<strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong> l’entreprise.<br />

Résultats <strong>et</strong> discussion<br />

Eu égard à l’approche <strong>de</strong> contingence utilisée <strong>dans</strong> c<strong>et</strong>te recherche, une analyse typologique<br />

(« cluster analysis ») fut effectuée afin d’i<strong>de</strong>ntifier, au sein <strong>de</strong> l’échantillon, différents profils <strong>de</strong><br />

comportement <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>PME</strong> en ce qui concerne l’étendue d’application <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. L’analyse<br />

typologique a pour objectif <strong>de</strong> classer <strong>les</strong> organisations en groupes (« clusters ») <strong>de</strong> façon à ce que chaque<br />

groupe soit très homogène par rapport à certains attributs. Ici, <strong>les</strong> attributs (ou variab<strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong> classification)<br />

sont <strong>les</strong> dix <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. Un second objectif est que chaque groupe diffère <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> autres en regard <strong>de</strong><br />

ces mêmes attributs. L’algorithme TwoStep du progiciel SPSS fut utilisé à c<strong>et</strong> eff<strong>et</strong>, étant donné que le<br />

nombre optimal <strong>de</strong> groupes y est déterminé <strong>de</strong> façon automatique. Une solution à trois groupes fut ainsi<br />

déterminée comme étant la plus parcimonieuse, chaque groupe présentant un profil clairement distinct<br />

<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> autres sur la base d’une configuration signifiante <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> variab<strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong> classification. Ces trois groupes<br />

sont différenciés par <strong>les</strong> qualificatifs « stratégique », « fonctionnel » <strong>et</strong> « traditionnel ». On notera qu’il<br />

s’agit ici d’une taxonomie <strong>et</strong> non d’une typologie <strong>de</strong> comportement <strong>GRH</strong> <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>PME</strong> <strong>dans</strong> la mesure où ces<br />

profils sont déterminés a posteriori <strong>et</strong> non théorisés a priori (Miller, 1996). Comme on peut l’observer au<br />

50

tableau 1, <strong>les</strong> différences observées entre <strong>les</strong> différents profils <strong>de</strong>meurent significatives même après avoir<br />

introduit la taille comme covariante.<br />

Tableau 1<br />

<strong>Profil</strong>s <strong>GRH</strong> résultant d’une analyse typologique <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>PME</strong> (n = 176)<br />

<strong>Profil</strong> <strong>GRH</strong><br />

Groupe<br />

stratégique<br />

(n = 30)<br />

moyenne<br />

Groupe<br />

fonctionnel<br />

(n = 75)<br />

moyenne<br />

Groupe<br />

traditionnel<br />

(n = 71)<br />

moyenne<br />

ANOVA<br />

F<br />

ANOVA<br />

F<br />

avec la Taille<br />

comme covariante<br />

Pratiques <strong>GRH</strong><br />

Descriptions <strong>de</strong> tâches 3,5 1 3,7 1 1,9 2 27,1*** 25,9***<br />

Recrutement 2,8 1 2,1 2 0,5 3 28,1*** 24,9***<br />

Évaluation du ren<strong>de</strong>ment 3,0 1 3,2 1 0,7 2 57,2*** 55,3***<br />

Formation ,005 ,007 1 ,004 2 4,1* 4,5**<br />

Information stratégique 13,8 1 12,0 2 9,1 3 58,0*** 55,6***<br />

Information économique 9,1 1 9,0 1 6,6 2 17,9*** 17,3***<br />

Information opérationnelle 20,6 1 20,4 1 16,1 2 24,1*** 22,3***<br />

Consultation 2,9 1 2,9 1 2,5 2 4,0* 4,5*<br />

Partage <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> profits 4,2 1 0,3 2 0,5 2 209,1*** 189,4***<br />

Accès à la propriété 1,5 1 0,1 2 0,1 2 28,3*** 23,0***<br />

*: p < 0,05 **: p < 0,01 ***: p < 0,001<br />

Nota. À l’intérieur <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> rangs, différentes annotations indiquent <strong>les</strong> différences significatives (p < 0,05) obtenues<br />

suite à un test (post hoc) <strong>de</strong> comparaison par paires T2 <strong>de</strong> Tamhane.<br />

Un premier coup d’œil perm<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> constater que <strong>les</strong> moyennes obtenues concernant l’étendue<br />

d’application <strong>de</strong> chacune <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> s’avèrent systématiquement plus faib<strong>les</strong> <strong>dans</strong> le groupe à<br />

profil traditionnel (n = 71) que <strong>dans</strong> <strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong>ux autres groupes. Ces <strong>PME</strong> sont cel<strong>les</strong> qui présentent le<br />

système <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> le moins développé, c’est-à-dire que <strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>, lorsqu’el<strong>les</strong> sont appliquées,<br />

s’adressent la plupart du temps à un nombre restreint <strong>de</strong> catégories d’employés, d’où <strong>les</strong> moyennes<br />

d’étendue plus faib<strong>les</strong> obtenues pour la gran<strong>de</strong> majorité <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong>.<br />

Les <strong>PME</strong> du groupe « fonctionnel » (n = 75), par ailleurs, se situent un peu à mi-chemin entre <strong>les</strong><br />

<strong>de</strong>ux autres groupes, avec <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> étendues d’application généralement supérieures à cel<strong>les</strong> du groupe<br />

traditionnel, mais souvent inférieures à cel<strong>les</strong> du groupe stratégique. Bien qu’el<strong>les</strong> soient <strong>de</strong> taille<br />

comparable aux <strong>PME</strong> du groupe traditionnel, <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> du groupe fonctionnel font preuve d’un<br />

comportement <strong>GRH</strong> n<strong>et</strong>tement distinct, investissant davantage <strong>dans</strong> toutes <strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong>, sauf cel<strong>les</strong> liées<br />

à la rémunération incitative (partage <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> profits <strong>et</strong> accès à la propriété). Ces <strong>PME</strong> sont également cel<strong>les</strong><br />

qui investissent le plus (en proportion <strong>de</strong> leurs ventes tota<strong>les</strong>) <strong>dans</strong> <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> activités <strong>de</strong> formation. Il semble<br />

donc que <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>PME</strong> <strong>de</strong> taille similaire en arrivent à un certain moment à prendre <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> orientations <strong>GRH</strong><br />

fortement distinctes, <strong>les</strong> unes (groupe traditionnel) optant pour un système minimal, <strong>les</strong> autres (groupe<br />

fonctionnel) choisissant plutôt d’investir considérablement <strong>dans</strong> le développement <strong>de</strong> leur système.<br />

Certains éléments <strong>de</strong> contexte perm<strong>et</strong>tant <strong>de</strong> mieux comprendre <strong>les</strong> motifs justifiant le choix d’une telle<br />

orientation seront examinés plus loin.<br />

Les <strong>PME</strong> du groupe stratégique (n = 30), quant à el<strong>les</strong>, se démarquent par l’étendue d’application<br />

<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> recrutement, d’information stratégique, <strong>de</strong> partage <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> profits <strong>et</strong> d’accès à la propriété.<br />

Pour ces quatre <strong>pratiques</strong>, l’étendue d’application est significativement plus gran<strong>de</strong> <strong>dans</strong> le groupe<br />

stratégique que <strong>dans</strong> <strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong>ux autres groupes. Tout en étant celui qui compte le moins <strong>de</strong> <strong>PME</strong> (17% <strong>de</strong><br />

l’échantillon comparativement à plus <strong>de</strong> 40% pour chacun <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>de</strong>ux autres groupes), le groupe<br />

51

stratégique est aussi celui qui démontre la plus forte orientation <strong>GRH</strong>. Notons que <strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong><br />

distinctives caractérisant ce groupe constituent un ensemble cohérent : il semble que l’on cherche ici à<br />

mieux choisir <strong>les</strong> candidats à l’entrée (recrutement), à <strong>les</strong> tenir bien informés <strong>de</strong> la mission, <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> objectifs<br />

<strong>et</strong> <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> résultats obtenus (diffusion d’informations stratégiques) <strong>et</strong> à <strong>les</strong> faire participer au succès financier<br />

<strong>de</strong> l’entreprise (partage <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> profits <strong>et</strong> accès à la propriété), autant <strong>de</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> susceptib<strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong> contribuer<br />

au développement d’un sentiment d’appartenance chez <strong>les</strong> employés <strong>et</strong> à favoriser leur motivation <strong>et</strong> leur<br />

fidélisation (Fabi, Lacoursière, Vallée <strong>et</strong> Gélinas, 2006).<br />

En réponse à notre première question <strong>de</strong> recherche, il ressort <strong>de</strong> ce qui précè<strong>de</strong> que, nonobstant<br />

leur taille, <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> <strong>de</strong> l’échantillon analysé présentent trois profils <strong>de</strong> comportement n<strong>et</strong>tement distincts<br />

en ce qui concerne <strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. Plus précisément, on distingue un premier groupe <strong>de</strong> <strong>PME</strong><br />

présentant une forte orientation <strong>GRH</strong> (groupe stratégique), un <strong>de</strong>uxième groupe présentant une<br />

orientation <strong>GRH</strong> moyenne (groupe fonctionnel) <strong>et</strong> un troisième groupe présentant une faible orientation<br />

<strong>GRH</strong> (groupe traditionnel). Les <strong>pratiques</strong> par <strong>les</strong>quel<strong>les</strong> se démarquent principalement <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> du<br />

groupe stratégique concernent le recrutement, la diffusion d’information stratégique, le partage <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

profits <strong>et</strong> la possibilité d’accès à la propriété (actionnariat); ces quatre <strong>pratiques</strong> y font l’obj<strong>et</strong> d’une<br />

étendue d’application significativement plus gran<strong>de</strong> que <strong>dans</strong> chacun <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>de</strong>ux autres groupes.<br />

En ce qui concerne la <strong>de</strong>uxième question <strong>de</strong> recherche, le tableau 2 perm<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> constater que<br />

plusieurs indicateurs servant à mesurer <strong>les</strong> variab<strong>les</strong> contextuel<strong>les</strong> sont associés <strong>de</strong> façon significative aux<br />

différents profils <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. Ici encore, <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> analyses <strong>de</strong> variance (ANOVA) ont été effectuées en vue<br />

d’établir le niveau <strong>de</strong> signification <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> coefficients obtenus. Une première analyse (5 e colonne) a été<br />

effectuée indépendamment <strong>de</strong> la taille tandis qu’une <strong>de</strong>uxième analyse (6 e colonne) en tenait compte.<br />

Une fois la taille contrôlée, sept indicateurs sur un total <strong>de</strong> 14 s’avèrent associés significativement aux<br />

profils <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. Ces indicateurs concernent le secteur (intensité technologique), la stratégie<br />

(développement <strong>de</strong> réseaux), la structure (présence d’un conseil d’administration, présence d’un<br />

responsable RH), le dirigeant (niveau <strong>de</strong> scolarité) <strong>et</strong> la technologie (présence d’une norme <strong>de</strong> qualité,<br />

applications informatisées <strong>de</strong> planification / logistique). La seule variable du modèle <strong>de</strong> recherche qui ne<br />

soit pas associée significativement aux profils <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> une fois la taille contrôlée est celle <strong>de</strong> la clientèle.<br />

En observant le tableau 2, on constate que <strong>les</strong> entreprises du groupe traditionnel se distinguent <strong>de</strong><br />

chacun <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>de</strong>ux autres groupes par un plus faible développement <strong>de</strong> leurs réseaux, par l’absence plus<br />

fréquente d’un conseil d’administration, d’un responsable RH, <strong>et</strong> d’une norme <strong>de</strong> qualité ainsi que par une<br />

moins bonne maîtrise <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> applications <strong>de</strong> planification / logistique (p. ex., MRP, MRP II). Autrement dit,<br />

<strong>les</strong> entreprises où <strong>les</strong> systèmes <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> sont <strong>les</strong> moins développés se caractérisent notamment par <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

partenariats moins diversifiés, une structure <strong>de</strong> gestion plus simple <strong>et</strong> une technologie moins sophistiquée.<br />

L’absence d’un conseil d’administration <strong>et</strong> d’un responsable RH pourraient signifier un rôle prépondérant<br />

du propriétaire dirigeant <strong>dans</strong> la prise <strong>de</strong> décisions <strong>et</strong> <strong>dans</strong> la gestion <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> opérations.<br />

52

Tableau 2<br />

Variab<strong>les</strong> contextuel<strong>les</strong> associées aux profils <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes <strong>GRH</strong><br />

<strong>Profil</strong> <strong>GRH</strong><br />

Groupe<br />

stratégique<br />

(n = 30)<br />

moyenne<br />

Groupe<br />

fonctionnel<br />

(n = 75)<br />

moyenne<br />

Groupe C<br />

traditionnel<br />

(n = 71)<br />

moyenne<br />

ANOVA<br />

F<br />

ANOVA<br />

F<br />

avec Taille<br />

covariante<br />

Variable<br />

Secteur<br />

Niveau d’intensité technologique a 0,27 0,23 0,11 2,3 3,0*<br />

Clientèle (dépendance)<br />

% <strong>de</strong> ventes aux 3 principaux clients 33 1 44 47 2 4,1* 2,1<br />

Taille<br />

nombre d’employés 96 1 62 2 56 2 8,3*** -<br />

Stratégie<br />

Développement <strong>de</strong> réseaux<br />

nombre <strong>de</strong> partenariats b 4,4 4,8 1 2,2 2 8,1*** 7,5***<br />

Développement <strong>de</strong> produits<br />

budg<strong>et</strong> R & D / ventes 0,020 0,029 0,022 0,6 0,5<br />

Développement <strong>de</strong> marchés<br />

ventes exportées / ventes 0,24 0,25 0,16 2,4 2,0<br />

Structure<br />

présence conseil d’administration 0,87 1 0,89 1 0,58 2 12,5*** 11,3***<br />

présence syndicat 0,33 0,35 0,25 0,8 0,8<br />

présence responsable RH 0,60 0,59 1 0,37 2 4,4* 3,6*<br />

Dirigeant<br />

niveau <strong>de</strong> scolarité du propriétaire c 3,6 1 3,1 2 3,0 2 4,6* 3,5*<br />

Technologie<br />

Type <strong>de</strong> production<br />

% <strong>de</strong> production en p<strong>et</strong>its lots d 37 27 21 2,3 1,4<br />

présence d’une norme <strong>de</strong> qualité 0,69 1 0,56 1 0,34 2 6,7** 5,1**<br />

Maîtrise du système <strong>de</strong> fabrication e<br />

technologies <strong>de</strong> conception produit 6,8 6,9 6,4 0,1 0,5<br />

technologies <strong>de</strong> production 5,0 5,1 4,3 0,4 1,3<br />

applications planif. / logistique 12,8 1 9,9 1 7,3 2 7,2*** 4,1*<br />

*: p < 0,05 **: p < 0,01 ***: p < 0,001<br />

Nota. Sur chaque rangée, <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> indices différents dénotent une différence significative (p < 0,05) entre <strong>les</strong> moyennes,<br />

suite à un test (post hoc) T2 <strong>de</strong> Tamhane.<br />

a associé au secteur d’activité manufacturière (0: faible ou faible à moyen, 1: moyen à élevé)<br />

b partenariats avec <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> sous-traitants, <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> clients, <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> fournisseurs, <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> compétiteurs, <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> centres recherche, collèges,<br />

universités <strong>et</strong> autres <strong>PME</strong> à <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> fins d’approvisionnement, conception, R&D, production, distribution <strong>et</strong> mark<strong>et</strong>ing.<br />

c niveau <strong>de</strong> scolarité = primaire:1, secondaire: 2, collégial: 3, universitaire: 4<br />

d <strong>de</strong> type “job shop”<br />

e Σ k=1,6 [niveau <strong>de</strong> maîtrise perçu du système avancé <strong>de</strong> fabrication k adopté, sur une échelle <strong>de</strong> 1 à 5]<br />

technologies <strong>de</strong> conception <strong>de</strong> produit = conception assistée par ordinateur, DAO, FAO, CAO/FAO<br />

technologies <strong>de</strong> production = opération robotisée, manutention automatisée, machines à contrôle<br />

numérique, automates programmab<strong>les</strong>, cellu<strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong> fabrication flexib<strong>les</strong><br />

planification <strong>et</strong> logistique = ordonnancement, co<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> zébrés, EDI, MRP, MRP-II, ERP<br />

53

Par ailleurs, <strong>les</strong> entreprises du groupe stratégique se démarquent principalement par leur taille –<br />

significativement plus gran<strong>de</strong> que celle <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> entreprises <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>de</strong>ux autres groupes – <strong>et</strong> le niveau <strong>de</strong> scolarité<br />

<strong>de</strong> leur propriétaire dirigeant, également plus élevé que <strong>dans</strong> <strong>les</strong> <strong>de</strong>ux autres groupes. Les <strong>PME</strong> <strong>de</strong> ce<br />

groupe possè<strong>de</strong>nt également une clientèle plus diversifiée (plus faible dépendance commerciale) que <strong>les</strong><br />

<strong>PME</strong> à orientation <strong>GRH</strong> traditionnelle.<br />

Finalement, <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> du groupe fonctionnel s’avèrent comparab<strong>les</strong> tantôt à cel<strong>les</strong> du groupe<br />

traditionnel, tantôt à cel<strong>les</strong> du groupe stratégique. Les ressemblances avec le groupe traditionnel<br />

concernent principalement la taille <strong>et</strong> le niveau <strong>de</strong> scolarité du propriétaire. Quant aux ressemblances avec<br />

le groupe stratégique, el<strong>les</strong> s’observent principalement au niveau <strong>de</strong> la structure (présence d’un conseil<br />

d’administration, présence d’un responsable RH) <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> la technologie (présence d’une norme <strong>de</strong> qualité,<br />

maîtrise <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> applications <strong>de</strong> planification / logistique).<br />

Comme le démontrent <strong>les</strong> résultats qui précè<strong>de</strong>nt, la taille à elle seule ne suffit pas à expliquer <strong>les</strong><br />

différences <strong>de</strong> profils <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> observab<strong>les</strong> au sein <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>PME</strong> <strong>de</strong> l’échantillon analysé. Même si el<strong>les</strong> sont<br />

<strong>de</strong> tail<strong>les</strong> comparab<strong>les</strong>, <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> appartenant aux groupes traditionnel <strong>et</strong> fonctionnel affichent <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

orientations <strong>GRH</strong> n<strong>et</strong>tement différentes, ces <strong>de</strong>rnières développant davantage la plupart <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> aspects <strong>de</strong><br />

leur système <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. Des variab<strong>les</strong> contextuel<strong>les</strong> autres que la taille doivent être prises en compte pour<br />

mieux comprendre <strong>les</strong> choix divergents effectués par ces <strong>de</strong>ux groupes <strong>de</strong> <strong>PME</strong> en ce qui concerne le<br />

développement <strong>de</strong> leurs systèmes <strong>GRH</strong>. Parmi ces variab<strong>les</strong> figurent notamment <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> éléments <strong>de</strong> stratégie<br />

(développement <strong>de</strong> réseaux), <strong>de</strong> structure (présence d’un conseil d’administration, présence d’un<br />

responsable RH) <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> technologie (présence d’une norme <strong>de</strong> qualité, niveau <strong>de</strong> maîtrise <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> applications<br />

informatisées <strong>de</strong> planification / logistique). Bien que <strong>de</strong> taille comparable, <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> du groupe fonctionnel<br />

renforceraient leur orientation <strong>GRH</strong> en réaction à différentes pressions émanant soit <strong>de</strong> leur réseau <strong>de</strong><br />

partenaires, soit <strong>de</strong> leur conseil d’administration ou soit encore pour mieux répondre à <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> exigences<br />

technologiques (norme <strong>de</strong> qualité, applications informatisées <strong>de</strong> planification / logistique). La présence<br />

d’un responsable RH pourrait à la fois être considérée comme un facteur <strong>de</strong> pression en faveur du<br />

renforcement <strong>de</strong> l’orientation <strong>GRH</strong> <strong>et</strong> comme un facteur facilitant la mise en œuvre <strong>de</strong> c<strong>et</strong>te orientation.<br />

Pour leur part, <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> du groupe stratégique se démarquent <strong>de</strong> cel<strong>les</strong> du groupe fonctionnel par<br />

une taille plus importante, certes, mais aussi par le niveau <strong>de</strong> scolarité plus élevé du propriétaire dirigeant<br />

<strong>et</strong> par une clientèle plus diversifiée. Ces éléments <strong>de</strong> contexte peuvent contribuer à expliquer le bond<br />

significatif que l’on constate <strong>dans</strong> l’application plus étendue <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> rémunération incitative, <strong>de</strong><br />

recrutement <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> diffusion d’informations stratégiques. Tel qu’évoqué précé<strong>de</strong>mment, ce bloc <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> distinctives caractérisant <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> du groupe à orientation <strong>GRH</strong> stratégique constitue<br />

un ensemble cohérent susceptible <strong>de</strong> favoriser le développement d’un sentiment d’appartenance chez <strong>les</strong><br />

employés tout en contribuant à leur motivation <strong>et</strong> à leur fidélisation. Les <strong>PME</strong> en général se plaignent<br />

fréquemment <strong>de</strong> difficultés <strong>de</strong> recrutement, surtout lorsqu’el<strong>les</strong> doivent recourir à une main-d’œuvre<br />

spécialisée. Le fait qu’el<strong>les</strong> atteignent une certaine taille peut augmenter <strong>les</strong> difficultés <strong>de</strong> recrutement <strong>de</strong><br />

ces <strong>PME</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>les</strong> inciter à développer leurs <strong>pratiques</strong> à c<strong>et</strong> égard. Le fait qu’el<strong>les</strong> transigent avec une<br />

clientèle plus diversifiée pourrait par ailleurs témoigner d’une plus gran<strong>de</strong> flexibilité <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>PME</strong> <strong>de</strong> ce<br />

groupe (stratégique), laquelle ne peut s’obtenir sans l’adhésion <strong>et</strong> la motivation <strong>de</strong> tous <strong>les</strong> membres <strong>de</strong><br />

l’organisation. La diffusion d’informations stratégiques (p. ex., mission, objectifs, résultats) à tous <strong>les</strong><br />

employés <strong>et</strong> le recours à <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> rémunération incitative peuvent faciliter c<strong>et</strong>te adhésion <strong>et</strong><br />

contribuer à la motivation <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> employés. Ces mêmes <strong>pratiques</strong> peuvent en outre s’avérer un facteur<br />

d’attraction <strong>et</strong> faciliter le recrutement d’employés qualifiés. Enfin, le fait qu’un dirigeant soit davantage<br />

scolarisé peut augmenter son sentiment <strong>de</strong> confiance <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> compétence, ce qui pourrait faciliter la mise en<br />

œuvre <strong>de</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> obligeant à une plus gran<strong>de</strong> transparence (diffusion d’informations<br />

stratégiques, partage <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> profits, accès à la propriété).<br />

54

R<strong>et</strong>ombées<br />

Les résultats <strong>de</strong> c<strong>et</strong>te recherche confirment la pertinence <strong>de</strong> recourir à l’approche <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes<br />

ouverts <strong>et</strong> à certains <strong>de</strong> ses embranchements, telle la théorie institutionnelle <strong>et</strong> la théorie <strong>de</strong> la dépendance<br />

en ressources comme cadre d’analyse <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> en <strong>PME</strong>. Bien que plusieurs <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> variab<strong>les</strong><br />

analysées <strong>dans</strong> c<strong>et</strong>te étu<strong>de</strong> aient déjà été i<strong>de</strong>ntifiées comme déterminant(s) <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>, la<br />

présente recherche est la première, à notre connaissance, à m<strong>et</strong>tre en relation d’une part, <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> profils <strong>de</strong><br />

comportement <strong>GRH</strong> avec, d’autre part, un aussi grand nombre <strong>de</strong> variab<strong>les</strong> contextuel<strong>les</strong>. Les étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

antérieures n’ont souvent pris en compte qu’un nombre limité (parfois même une seule) <strong>de</strong> variab<strong>les</strong><br />

contextuel<strong>les</strong> ou encore un nombre restreint <strong>de</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> (<strong>et</strong> parfois une seule). La présente<br />

recherche démontre qu’une approche contextuelle inspirée <strong>de</strong> la théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes ouverts perm<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong><br />

prendre en compte un nombre considérable d’éléments <strong>de</strong> contexte pouvant moduler <strong>les</strong> systèmes <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>GRH</strong> en contexte <strong>de</strong> <strong>PME</strong> manufacturières. Enfin, c<strong>et</strong>te étu<strong>de</strong> est la première, à notre connaissance, à<br />

faire ressortir le rôle déterminant que semble exercer la présence d’un conseil d’administration sur le<br />

développement <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. Ce résultat constitue un exemple concr<strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> la façon dont la théorie<br />

institutionnelle peut s’appliquer à la <strong>GRH</strong>. Le fait <strong>de</strong> soum<strong>et</strong>tre l’entreprise au regard <strong>de</strong> partenaires<br />

externes provenant <strong>de</strong> différents milieux peut constituer une pression favorisant la mise en place <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>pratiques</strong> reconnues.<br />

C<strong>et</strong>te recherche indique également aux gestionnaires <strong>et</strong> aux praticiens qu’il n’existe peut-être pas<br />

<strong>de</strong> solution « tout aller » en ce qui concerne <strong>les</strong> systèmes <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> <strong>et</strong> que la confection <strong>de</strong> systèmes « sur<br />

mesure » semble coller davantage à la réalité <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>PME</strong>, laquelle se façonne à partir <strong>de</strong> pressions <strong>de</strong> toutes<br />

sortes : pressions <strong>de</strong> l’environnement <strong>et</strong> <strong>de</strong> la concurrence certes, mais aussi pressions attribuab<strong>les</strong> aux<br />

clients, aux partenaires, aux dirigeants <strong>et</strong> à la technologie.<br />

Par ailleurs, c<strong>et</strong>te recherche comporte aussi certaines limites. Bien que <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> <strong>de</strong> l’échantillon<br />

s’avèrent relativement représentatives <strong>de</strong> la population canadienne <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>PME</strong> manufacturières en ce qui<br />

concerne leur taille <strong>et</strong> leur secteur d’activité, il pourrait exister un biais attribuable au fait que ces <strong>PME</strong><br />

ont volontairement choisi <strong>de</strong> participer à un exercice <strong>de</strong> benchmarking (étalonnage), ce qui pourrait <strong>les</strong><br />

différencier <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> autres <strong>PME</strong> en ce qui concerne, notamment, leur orientation stratégique <strong>et</strong> leur niveau <strong>de</strong><br />

développement (Cassel, Nadin <strong>et</strong> Gray, 2001). Bien que plusieurs caractéristiques aient été prises en<br />

considération <strong>dans</strong> la présente étu<strong>de</strong>, d’autres pourraient aussi exercer une influence sur le choix <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

<strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> à m<strong>et</strong>tre en place. Finalement, un nombre limité <strong>de</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> a été pris en<br />

considération <strong>dans</strong> la présente étu<strong>de</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>les</strong> informations contenues <strong>dans</strong> la base <strong>de</strong> données relativement à<br />

chacune <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> fournissent peu d’indications quant à la façon dont cel<strong>les</strong>-ci s’articulent.<br />

Conclusion<br />

S’inspirant <strong>de</strong> la théorie <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes ouverts, la présente étu<strong>de</strong> avait pour but <strong>de</strong> vérifier si l’on<br />

peut observer, en contexte <strong>de</strong> <strong>PME</strong> manufacturières, <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> différences <strong>de</strong> comportements <strong>dans</strong> le<br />

développement <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> <strong>et</strong>, le cas échéant, à vérifier si <strong>les</strong> profils <strong>de</strong> comportement observés<br />

pouvaient être associés à <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> éléments <strong>de</strong> contexte d’ordre environnemental, organisationnel,<br />

technologique ou autre.<br />

L’analyse <strong>de</strong> données d’enquête révèle que <strong>les</strong> <strong>PME</strong> peuvent être regroupées sous trois profils<br />

distincts caractérisés par une faible (groupe traditionnel), moyenne (groupe fonctionnel) ou forte (groupe<br />

stratégique) orientation <strong>GRH</strong>. Chacun <strong>de</strong> ces profils s’avère associé à <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> éléments contextuels distinctifs<br />

55

dont la taille, tel que prévu, mais aussi le secteur <strong>dans</strong> lequel el<strong>les</strong> opèrent, la formation du propriétaire<br />

dirigeant, la structure organisationnelle <strong>et</strong> <strong>les</strong> technologies utilisées.<br />

Les résultats obtenus confirment que l’approche <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes ouverts peut enrichir notre<br />

compréhension <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> différents facteurs contribuant à façonner <strong>les</strong> systèmes <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong> développés <strong>dans</strong> <strong>les</strong><br />

<strong>PME</strong>. En ce sens, l’approche <strong>de</strong> systèmes ouverts constitue un complément intéressant à l’approche<br />

« resource-based view » <strong>et</strong> aux approches d’alignement stratégique (contingence, configuration) souvent<br />

utilisées en contexte <strong>de</strong> gran<strong>de</strong> entreprise pour justifier <strong>les</strong> choix <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong>. Sachant que la <strong>GRH</strong> en <strong>PME</strong><br />

s’avère davantage réactive que planifiée, la possibilité qu’offrent <strong>les</strong> approches systémiques – tel<strong>les</strong> par<br />

exemple celle <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes ouverts ou celle <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> systèmes complexes – <strong>de</strong> prendre en compte un grand<br />

nombre <strong>de</strong> variab<strong>les</strong> contextuel<strong>les</strong> pourrait faire en sorte que cel<strong>les</strong>-ci conviennent mieux à l’analyse <strong>de</strong> la<br />

<strong>GRH</strong> en <strong>PME</strong> que <strong>les</strong> approches précé<strong>de</strong>ntes (contingence, configuration, RBV) reposant sur un postulat<br />

<strong>de</strong> rationalité <strong>et</strong> supposant une planification sophistiquée.<br />

Annexe 1<br />

Liste <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> empiriques ayant examiné <strong>les</strong> eff<strong>et</strong>s <strong>de</strong> différentes variab<strong>les</strong><br />

sur <strong>les</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong><br />

Auteurs <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> Pays n <strong>PME</strong><br />

(0-100)<br />

<strong>PME</strong><br />

(0-250)<br />

1 Aragon-Sanchez <strong>et</strong> Sanchez-Marin (2005) Espagne 1 361 √<br />

2 Bacon, Ackers, Storey <strong>et</strong> Coates (1996) Royaume-Uni 229 √<br />

<strong>PME</strong><br />

(0-500)<br />

3 Barber, Wesson, Roberson <strong>et</strong> Taylor (1999) États-Unis 303 √<br />

4 Baron, Hannan <strong>et</strong> Burton (1999) États-Unis 76 √<br />

5 Bayo-Moriones <strong>et</strong> Merino-Diaz <strong>de</strong> Cerio (2004) Espagne 965 √<br />

6 Beaumont, Hunter <strong>et</strong> Sinclair (1996) Royaume-Uni 156 √<br />

7 Budhwar <strong>et</strong> Khatri (2001) Royaume-Uni \ In<strong>de</strong> 93 √<br />

8 Cassell, Nadin, Gray <strong>et</strong> Clegg (2002) Royaume-Uni 122 √<br />

9 Chowhan (2005) Canada 5 501 √<br />

10 Deshpan<strong>de</strong> <strong>et</strong> Golhar (1994) États-Unis 100 √<br />

11 Golhar <strong>et</strong> Deshpan<strong>de</strong> (1997) Canada 143 √<br />

12 Gudmundson <strong>et</strong> Hartenian (2000) États-Unis 207 √<br />

13 Guilhon, Martin <strong>et</strong> Weill (1998) France 42 √<br />

14 Hanks <strong>et</strong> Chandler (1994) États-Unis 133 √<br />

15 Hausdorf <strong>et</strong> Duncan (2004) Canada 175 √<br />

16 Heneman <strong>et</strong> Berkley (1999) États-Unis 117 √<br />

17 Kinnie <strong>et</strong> al. (1999) Royaume-Uni 3 √<br />

18 Knoke <strong>et</strong> Kalleberg (1994) États-Unis 688 √<br />

19 Kok (De) <strong>et</strong> Uhlaner (2001) Hollan<strong>de</strong> 16 √<br />

20 Kotey <strong>et</strong> Sla<strong>de</strong> (2005) Australie 371 √<br />

21 Kuratko <strong>et</strong> Hornsby (2001) États-Unis 184 √<br />

22 Machin <strong>et</strong> Wood (2005) Royaume-Uni 7 000 √<br />

23 Mak <strong>et</strong> Akhtar (2003) Hong Kong 63 √<br />

24 Matlay (1999) Royaume-Uni 6 000 √<br />

25 Mazzarol (2003) Australie 4 √<br />

26 Messeghem (2003) France 72 √<br />

27 Ng <strong>et</strong> Maki (1993) Canada 356 √<br />

28 Nguyen <strong>et</strong> Bryant (2004) Vi<strong>et</strong>nam 89 √<br />

29 Otham (Bin) <strong>et</strong> Poon (2000) Malaisie 108 √<br />

30 Peck (1994) États-Unis 63 √<br />

31 Poutsma, Hendrickx <strong>et</strong> Huijgen (2003) Europe (10) 4 600 √<br />

32 Raghuram <strong>et</strong> Arvey (1994) États-Unis 176 √<br />

<strong>PME</strong><br />

<strong>et</strong> GE<br />

56

33 Reid, Morrow, Kelly, Adams <strong>et</strong> McCartan (2000) Irlan<strong>de</strong> du Nord 219 √<br />

34 Rutherford, Buller <strong>et</strong> McMullen (2003) États-Unis 2 903 √<br />

35 Sanz-Valle, Sabater-Sanchez <strong>et</strong> Aragon-Sanchez (1999) Espagne 200 √<br />

36 Shah <strong>et</strong> Ward (2003) États-Unis 1 748 √<br />

37 Schuler <strong>et</strong> Harris (1991) États-Unis 1 √<br />

38 Schuler <strong>et</strong> Jackson (1987) États-Unis 304 √<br />

39 SHRM (2002) États-Unis 571 √<br />

40 Swart <strong>et</strong> Kinnie (2003) Royaume-Uni 3 √<br />

41 Turcotte, Léonard <strong>et</strong> Montmarqu<strong>et</strong>te (2003) Canada 6 322 √<br />

42 Verheul, Risseeuw <strong>et</strong> Bartelse (2002) Hollan<strong>de</strong> 28 √<br />

43 Wagar (1998) Canada 991 √<br />

44 Way <strong>et</strong> Thacker (2004) Canada 202 √<br />

45 Weinstein <strong>et</strong> Obloj (2002) Pologne 303 √<br />

Annexe 2<br />

Classification <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> selon <strong>les</strong> déterminants analysés <strong>et</strong> nature <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> impacts observés<br />

Impacts sur le développement <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> <strong>pratiques</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>GRH</strong><br />

Déterminants Impact positif Impact négatif Aucun impact<br />

Taille<br />

(incluant croissance)<br />

2 a -3-4-7-9-10-11-15-16-<br />

18-19-20-25-27-28-31-<br />

34-36-39-41-43-45<br />

5-39<br />

Stratégie<br />

(innovation, qualité, <strong>et</strong>c.)<br />

1-5-13-19-21-23-26-29-<br />

30-32-35-37-38-41-45<br />

45 8<br />

Présence syndicale 7-9-31-41-43 19-27-36 5-18-22-45<br />

Secteur d’activité (industrie) 1-7-16 -41 31-45 9<br />

Propriétaire (entrepreneur) 2-4-12-24-25-42 42<br />

Compétiteurs 5-9-18-31-45 41<br />

Clients 2-6-17-19-40<br />

Sta<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> développement 7-14-34-39<br />

Technologie 5-9-31-41<br />

Âge 7 36 5-34<br />

Caractéristiques <strong>de</strong> la maind’œuvre<br />

9-31-41 18<br />

Présence d’un responsable RH 16-44<br />

Entreprise familiale 33<br />

a Les numéros utilisés pour la classification <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> correspon<strong>de</strong>nt aux numéros attribués à chacune <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> étu<strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong><br />

présentées à l’annexe 1.<br />

57

1. Taille<br />

2. Secteur (intensité techologique)<br />

3. Clientèle (dépendance commerciale)<br />

4. Développement <strong>de</strong> réseaux<br />

5. Développement <strong>de</strong> produits<br />

Annexe 3<br />

Matrice <strong><strong>de</strong>s</strong> corrélations entre <strong>les</strong> différentes variab<strong>les</strong> contextuel<strong>les</strong><br />

Correlation 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15.<br />

-<br />

-.08 -<br />

-.19 .00 -<br />

6. Développement <strong>de</strong> marchés<br />

7. Présence d’un conseil d’administration<br />

8. Présence d’un syndicat<br />

9. Présence d’un responsable RH<br />

10. Scolarité du propriétaire dirigeant<br />

11. Type <strong>de</strong> production<br />