FINANCE FOR ALL ? - Frankfurt School of Finance & Management

FINANCE FOR ALL ? - Frankfurt School of Finance & Management

FINANCE FOR ALL ? - Frankfurt School of Finance & Management

Sie wollen auch ein ePaper? Erhöhen Sie die Reichweite Ihrer Titel.

YUMPU macht aus Druck-PDFs automatisch weboptimierte ePaper, die Google liebt.

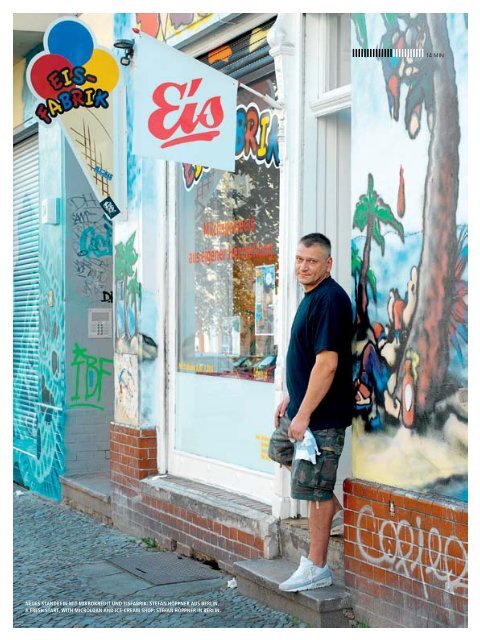

Neues Standbein mit Mikrokredit und Eisfabrik: Stefan Höppner aus Berlin.<br />

A FRESH START, WITH MICROLOAN AND ICE-CREAM SHOP: STEFAN HÖPPNER IN BERLIN.<br />

14 MIN