Understanding Clinical Trial Design - Research Advocacy Network

Understanding Clinical Trial Design - Research Advocacy Network

Understanding Clinical Trial Design - Research Advocacy Network

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

30<br />

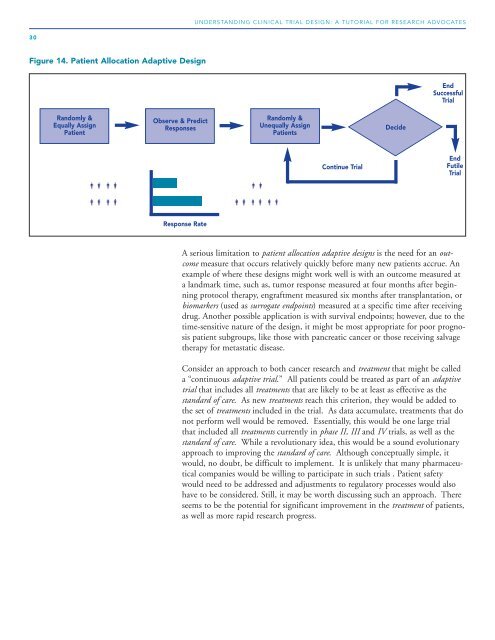

Figure 14. Patient Allocation Adaptive <strong>Design</strong><br />

Randomly &<br />

Equally Assign<br />

Patient<br />

Observe & Predict<br />

Responses<br />

Response Rate<br />

UNDERSTANDING CLINICAL TRIAL DESIGN: A TUTORIAL FOR RESEARCH ADVOCATES<br />

Randomly &<br />

Unequally Assign<br />

Patients<br />

Continue <strong>Trial</strong><br />

Decide<br />

End<br />

Successful<br />

<strong>Trial</strong><br />

End<br />

Futile<br />

<strong>Trial</strong><br />

A serious limitation to patient allocation adaptive designs is the need for an outcome<br />

measure that occurs relatively quickly before many new patients accrue. An<br />

example of where these designs might work well is with an outcome measured at<br />

a landmark time, such as, tumor response measured at four months after beginning<br />

protocol therapy, engraftment measured six months after transplantation, or<br />

biomarkers (used as surrogate endpoints) measured at a specific time after receiving<br />

drug. Another possible application is with survival endpoints; however, due to the<br />

time-sensitive nature of the design, it might be most appropriate for poor prognosis<br />

patient subgroups, like those with pancreatic cancer or those receiving salvage<br />

therapy for metastatic disease.<br />

Consider an approach to both cancer research and treatment that might be called<br />

a “continuous adaptive trial.” All patients could be treated as part of an adaptive<br />

trial that includes all treatments that are likely to be at least as effective as the<br />

standard of care. As new treatments reach this criterion, they would be added to<br />

the set of treatments included in the trial. As data accumulate, treatments that do<br />

not perform well would be removed. Essentially, this would be one large trial<br />

that included all treatments currently in phase II, III and IV trials, as well as the<br />

standard of care. While a revolutionary idea, this would be a sound evolutionary<br />

approach to improving the standard of care. Although conceptually simple, it<br />

would, no doubt, be difficult to implement. It is unlikely that many pharmaceutical<br />

companies would be willing to participate in such trials . Patient safety<br />

would need to be addressed and adjustments to regulatory processes would also<br />

have to be considered. Still, it may be worth discussing such an approach. There<br />

seems to be the potential for significant improvement in the treatment of patients,<br />

as well as more rapid research progress.